Introduction

Single-lung ventilation, also known as 'one-lung' ventilation, involves ventilating one lung and letting the other collapse to provide surgical exposure in the thoracic cavity or isolating ventilation to one lung. The protective role of single-lung ventilation involves protecting one lung from the ill effects of fluid from the other lung, which may be blood, lavage fluid, or malignant or purulent secretions. Thus, perfect placement of the tube is essential, as a misplaced tube defeats the goal of lung isolation or differential ventilation. Bronchoscopy after tube placement ensures proper placement.

Single-lung ventilation is used to facilitate procedures on ipsilateral thoracic or mediastinal structures and to provide lung isolation; this is made possible by using double-lumen tubes, bronchial blockers, and endobronchial tubes. Familiarity with the use of these instruments and the physiology of single-lung ventilation is essential to the performance of safe anesthesia.

This article will discuss the anatomy and physiology of single-lung ventilation, its indication/contraindications, equipment, and preparation. Traditional mechanical ventilation will be discussed separately.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

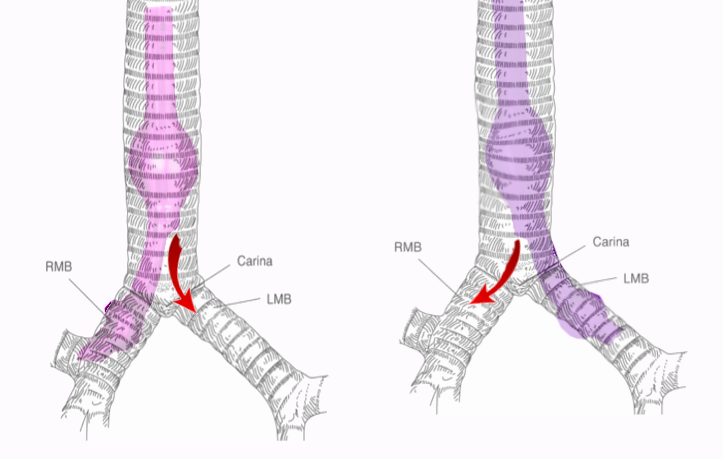

A good understanding of airway anatomy and the tracheobronchial tree is essential to performing safe single-lung ventilation, which is the preferred method for surgical interventions during thoracic procedures. The fiberoptic bronchoscopy enables a good visualization of the airway anatomy. The first branching point in the airway is the carina which marks the bifurcation of the trachea into the 2 mainstem bronchi at the level of the sternal angle, the left and right main bronchus. The trachea is about 10 to 13 cm long and has 12 concentric cartilaginous rings. These rings are deficient in their posterior aspect and thus for C-shaped rings as seen on a cross-section. The trachea divides in an area known as the carina, which marks the division into the left and right main bronchus (as depicted in the figure).

The left main bronchus (LMB) continues for about 5 cm, after which it branches into the left lower lobe bronchus (LLLB) and left upper lobe bronchus (LULB). The right main bronchus (RMB) is shorter than the left side, but it is also wider and more vertical than the left side. The right main bronchus gives off the right upper lobe bronchus and continues further as the bronchus intermedius. The take-off of the right upper lobe bronchus is about 2.0 cm in adult men and about 1.6 cm in adult females. A knowledge of tracheal anatomy helps the anesthesiologist to position the double-lumen tube for selectively isolating one lung for ventilation. This anatomy must undergo careful observation once the double lumen tube is in place and the fiberoptic scope is inserted to check the cuff position and verify correct tube placement.

During normal breathing, both lungs receive an equal amount of air for ventilation and blood flow for perfusion (based on gravitational forces). However, after starting single-lung ventilation, all ventilation goes to one lung only, which creates significant hypoxia related to right-to-left shunting (the shunt can reach up to 50%). However, the position of patients during surgeries can influence the amount of shunt as lungs become dependent on gravity. The ventilated lung is therefore affected and restricted by the weight of the contralateral hemithorax from one side and limitations of the chest wall from the other side. However, lung elastance is increased in the lateral position with single-lung ventilation during operations which may predispose to ventilator-associated lung injury.[2]

Indications

The indications of single-lung ventilation aim at facilitating surgical exposure by isolating the lung away from the field of surgery or preventing further lung trauma by providing selective ventilation and preventing infection or secretions from entering the healthy lung.

Surgical Exposure

- Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), including pneumonectomy and wedge resections

- Pulmonary resections include pneumectomies and lobectomies.

- Mediastinal surgery

- Thoracic vascular surgery

- Esophageal surgery

- Spine surgery

- Minimally invasive aortic or mitral valve replacement surgeries

Lung Isolation

For protective isolation to prevent contamination or spill of secretions to the other lung:

- Massive pulmonary hemorrhage

- Infection/purulent secretions

- Whole lung lavage in cases of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

For control of ventilation to decrease pressure or airflow through the affected side:

- Tracheobronchial trauma

- Broncho-pleural/broncho-cutaneous fistula

Contraindications

Some of the relative contraindications for single-lung ventilation are as follows:

- Patient unable to tolerate single-lung ventilation or dependent on bilateral ventilation

- Intraluminal airway masses (making DLT placement difficult)

- Hemodynamic instability

- Severe hypoxia

- Severe COPD

- Severe pulmonary hypertension.

- Known or suspected difficult intubation

Equipment

The method of single-lung ventilation was first conceptualized by physiologists Eduard Pflüger and Claude Bernard, who studied gas exchange in dogs using a lung-isolation catheter.[3] Wolffberg isolated the 2 lungs using the catheter in 1871, the first reported concept of an endobronchial single-lumen tube. Loewy and von Schrotter performed the first clinical use in humans with lower lobe bronchus catheterized under fluoroscopic control. Head designed the first double-lumen tube in 1889, which had 2 tracheal cannulas—one short tracheal and one longer endobronchial one. Gale and Walters, in 1932, advanced Head's design and created the prototype for the modern-day double-lumen tubes.

Double-lumen tubes (DLT) paved the way for single-lung ventilation, offering better ventilation control and more efficient separation of the 2 lungs. Single-lung ventilation is achieved using special airway devices such as double-lumen tubes and bronchial blockers, which selectively direct the airflow to one lung. They are used to collapse one lung selectively for surgery on the ipsilateral side. The choice and type of device to achieve lung separation depend on the patient's anatomy, the procedure, and the operator's preference.[4]

Double-Lumen Tubes: The most common design of the DLT used in the current practice of thoracic anesthesia is the Robertshaw design or disposable polyvinyl chloride (PVC). The Robertshaw design or PVC is available in left- and right-sided types and in varying sizes from 26 Fr to 41 Fr. The size denotes the external diameter of the tube in cm. The Robertshaw design of the DLT comprises 2 semicircles placed back to back to form 2 independent lumens that can be ventilated independently. [5]

The lumens have different openings depending on which side of the DLT is present. The right-sided DLT has a curve to the right, and the left-sided DLT has a curve to the left. The DLT cuffs are high-volume and low-pressure cuffs.[6][7]

Connector: The connector is an essential component of the DLT as it allows the user to selectively block either the lumen or ventilate bilaterally. The connector piece is composed of a Y-shaped piece with 2 openings—one each for the connection to the bronchial and tracheal lumen and a common portion that fits into the anesthesia circuit.

The connector usually has tracheal and bronchial lumen parts of different colors for ease of use. Manufacturers universally use the blue color to denote the endobronchial-lumen cuff. The cuffs are colored similarly to the connector tubes to maintain uniformity in identification. This safety mechanism ensures lung collapse and ventilation on the correct side, achieved by clamping the side on which the lung needs to collapse temporarily.

Bronchial Blockers: Bronchial blockers achieve single-lung ventilation by blocking either the left or right primary bronchus. Several manufacturers produce bronchial blockers with different designs. However, they have a simple design with an inflatable low-pressure, high-volume cuff at the end of a catheter.

The advantages of a bronchial blocker over a DLT include the ability to place through an existing endotracheal tube, to use in patients with airway trauma, and to perform selective lobar blockade if needed. Bronchial blockers are not without their disadvantages. They require a minimum of 7.5 endotracheal tubes in place for introduction into the airway. They allow the slower collapse of the lung. Owing to the variable take-off of the right upper lobe, bronchial blockers are often difficult to position to seal off the right upper lobe. They are also much more prone to dislodgement when compared to DLT.[8]

Fiber-optic Bronchoscope: A fiber-optic scope is mandatory when placing a DLT because accurate positioning is essential to achieve a good seal and lung isolation. To avoid malpositioned tubes, the tube position is checked after the patient is in the final position for the procedure.

Endobronchial Tubes: Endotracheal tubes may be placed to provide single-sided ventilation. The major disadvantage of using these is the inability to access the nonintubated lung. Endobronchial tubes are preferred in specific clinical scenarios to a DLT, such as for patients with previous neck or oral surgery who present with a difficult airway and require adequate lung separation.

The placement of a DLT is more challenging than an endobronchial SLT. DLT placement has a higher chance of airway injury and bleeding. Endobronchial tubes may be mandatory in patients requiring lung isolation who have a short- or long-term tracheostomy present before the procedure.[9][10][11]

Preparation

Clinical Considerations

Patients usually undergoing single-lung ventilation have underlying pulmonary disease. Patients should be evaluated comprehensively for their primary disease before performing the surgical procedure. Echocardiography may be useful in patients with cor pulmonale and may provide information about baseline cardiac function and reserve.[12]

Reviewing the relevant radiological anatomy on a case-to-case basis may help plan anesthetic management for single-lung ventilation. This review will also allow proper preparation for patients who require specialized airway management. Decreased baseline function due to large effusions, consolidations, and atelectasis predisposes patients to hypoxemia during the procedure, which may obviate the need to use higher fractions of inspired oxygen.

The presence of any bullae on the nonoperative lung may provide clues to patients more likely to develop a pneumothorax in the perioperative period. Tumors must be evaluated for paraneoplastic syndromes, as their presence may guide anesthetic management.[13] The use of standardized protocol has increased adherence to lung protective strategies in SLV (as discussed below).[14]

Special considerations must be placed on patients' age, as it is an independent risk factor related to complication rates in patients undergoing pulmonary resection using single-lung ventilation. Elderly patients have higher morbidity and mortality from pulmonary resections. Patients undergoing lung resections need additional testing to predict the risks involved in lung resection besides age. The most common tests for such an assessment are FEV1 (forced expiratory volume of one second) and DLCO (diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide).

FEV1 is a predictor of postoperative complications, including death that may arise from undergoing pulmonary resection. Multiple authors found a reduced preoperative FEV1 (less than 60% predicted) to be the strongest predictor of postoperative complications.[15][16] Therefore, a cutoff of 60% for FEV1 and DLCO is used to determine postoperative risk.[17]

The current ACCP guidelines do not provide numerical cutoffs for DLCO below which pulmonary resections should not be performed on patients. Instead, they give importance to determining the predicted postoperative (PPO) values. Assessment of the postoperative predicted values is the deciding factor in such cases and predicts the success of single lung ventilation. The interpretation of postoperative values is as follows:

- Patients with PPO FEV1 and PPO DLCO greater than 60% do not need further testing to undergo pulmonary resection.

- However, patients with PPO FEV1 or PPO DLCO less than 60% but greater than 30% need additional testing with stair climbing or a shuttle walk test.

- If both values are less than 30%, patients should undergo cardiopulmonary exercise testing with additional measurement of the maximal oxygen consumption.

The cutoff for the stair climb test is 22 meters. Using the Incremental Shuttle Walk test, a distance greater than 400 meters denotes a maximal oxygen uptake of (VO max) greater than or equal to 15 mL/kg/min. Such information may help the physician interpret the procedural risks and better clinical outcomes for patients undergoing single-lung ventilation.

Lung-Protective Strategy

This strategy is used for patients with an increased risk of developing acute lung injury (ALI) or progressing to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[1] It includes using a low tidal volume strategy developed after the landmark ARDSnet trials that showed a decrease in all-cause mortality.[18] A lung-protective strategy can play a role in preventing barotrauma, volume trauma, and atelectatic trauma and includes the following:

- Tidal volume should be initially set at 4 to 6 mL/kg based on ideal body weight (a lower dose than 6-8 mL/kg is recommended for mechanical ventilation using bilateral lungs).[19][18][20][21] The dose can be adjusted, and airway pressures are monitored to identify signs of alveolar trauma or injury which can be assessed by measuring inspiratory plateau pressures and targeting in non-obese a pressure of less than 30 cmH2O.

- A respiratory rate (RR) of 16 breaths per minute is appropriate initially for most patients to achieve normocapnia.[22] A blood gas should be sent approximately 30 minutes after initiation of mechanical ventilation, and RR should be adjusted based on the acid-base status and PaCO2 of the patient. If the PaCO2 is significantly greater than 40 mm Hg, then the RR should be increased. If the PaCO2 is significantly lower than 40, then the RR should be decreased.

- The inspiratory flow rate should be set at 60 L/min. If the patient appears to be trying to inhale more during the initiation of inspiration, it can increase.[23]

- Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is usually set at 5 to 10 cmH2O depending on hemodynamic status, oxygenation (FiO2 requirement), and the presence of obstructive lung disease or auto-PEEP. [24]

- The oxygenation goal of 88%- to 95% should follow the ARDSnet protocol.[20]

Technique or Treatment

The most commonly used DLT is the left-sided DLT, irrespective of which side requires the isolation because placing a left-sided DLT is less challenging than the right-sided one. This comparative ease is partly due to the short take-off of the right upper bronchus, which leads to higher chances of dislodgement and impaired ventilation of the right upper bronchus.

DLT-placement technique: After inducing the patient with general anesthesia and confirming complete neuromuscular blockade, the following steps are taken to place a left-sided DLT:

- A direct laryngoscopy using a Macintosh blade is used for laryngoscopy as the DLT is a large tube, and this technique provides the maximum space for its insertion.

- The DLT is introduced with a rigid stylet with the endobronchial curvature facing anteriorly.

- The rigid stylet ensures passage through the vocal cords. After the DLT passes through the vocal cords, the stylet is removed.

- The tube is then rotated by a 90-degree angle anticlockwise to the left until the blue bronchial lumen faces left and the tracheal lumen faces right.

- The next step involves either advancing the tube further until resistance is met or using a fibreoptic bronchoscope to guide further placement. The tracheal cuff may be inflated at this moment, and the connector is attached to start ventilation.

- The shape of the left-sided DLT facilitates the bronchial cuff to be positioned in the left bronchus when advanced; the DLT position should be confirmed with a fibreoptic bronchoscope to ensure the tracheal lumen opening is above the carina and bronchial lumen is in the left bronchus. The bronchial cuff can now be inflated with 1 to 2 mL of air.

- Bilateral ventilation confirmation is by auscultation. Air entry should be audible in bilateral lungs at this point.

- Next, lung isolation is confirmed with selective tracheal and bronchial lumens clamping.

- Only the left lung should be inflated when ventilation through the bronchial lumen completes.

- Only the right lung should inflate when clamping the bronchial lumen and ventilating through the tracheal lumen.

The inability to perform a direct laryngoscopy is a contraindication to using a DLT. In such a situation, a bronchial blocker may be a suitable alternative.

Complications

Hypoxemia: During single-lung ventilation, the ventilation to one of the lungs is interrupted. However, the perfusion is still present in the nonventilated lung, which leads to an intrapulmonary shunt in the form of wasted perfusion to the nonventilated lung.

Protective mechanisms like hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction can counteract hypoxia to a certain degree. However, the anesthesiologist must have measures in place for hypoxemia that may arise during single-lung ventilation. Ventilation and perfusion (V-Q) matching plays a significant role in the management of oxygenation in patients on single-lung ventilation. Some authors note that oxygenation is much better in the lateral decubitus position when compared to the supine position.[25]

Classically, an inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2) of 1.0 has been advocated while performing single-lung ventilation. The rationale behind using a higher inspired fraction of oxygen is to have a safety margin. Higher Fio2 also leads to vasodilatation, which may help increase the blood to the ventilated lung. Oxygenation at FiO2 of 1.0 can lead to atelectasis, so it is advisable to initiate with a Fio2 less than 1.0 and increase if needed.

If hypoxia develops during the performance of single-lung ventilation, the following steps must take place:

- Check the position of the double-lumen tube/endobronchial tube/bronchial blocker. Changes in position may occur due to surgical manipulation. A repeat fiberoptic bronchoscopy through the tracheal lumen is useful in clinching the diagnosis. Additional steps involve suctioning the lumens of the tube to clear secretions that may also contribute to hypoxia.

- FiO2 is increased to 1.0 to improve the amount of oxygen delivered.

- Recruitment maneuvers are employed on the ventilated lung, which is in the dependent position; these are performed to overcome any atelectasis and thus help oxygenation. PEEP may be applied to this lung to eliminate atelectasis, resulting in a decrease in the shunt, thereby improving oxygenation

- CPAP to the operative lung may be applied to decrease shunting and thus improve oxygenation. However, this does make the surgical procedure challenging to the surgeon, and should only be an option when other measures have not resulted in any improvement.

- If the hypoxemia is severe and does not resolve with the abovementioned steps, the next best step is to revert to 2-lung ventilation.

- Severe hypoxemia should alert the anesthesiologist to look for causes like pneumothorax on the dependent lung. Chronic obstructive lung disease patients are more likely to experience such a complication. Intraoperative development of pneumothorax mandates aborting the surgical procedure and immediate insertion of a chest tube on the side of the pneumothorax.

Ventilator-induced lung injuries: Using standardized protocol has been shown to increase adherence to lung-protective strategies in SLV.[14]

Clinical Significance

Body Positions and Ventilation

The lateral decubitus position: A change from the supine position to the lateral decubitus position brings about 2 physiological changes. Gravity increases blood flow in the dependent lung compared to the nondependent lung. However, there is also an increase in ventilation to the dependent lung. This change arises from the more efficient contraction of the dependent hemidiaphragm compared to the nondependent side. The dependent lung also lies in a more favorable part of the compliance curve.

The lateral decubitus position under anesthesia: Under anesthesia, there is a decrease in functional residual capacity. The upper lobe moves under anesthesia to a more favorable portion of the compliance curve versus the lower lung, which lies now on a less favorable portion of the compliance curve. Neuromuscular blockade contributes to abdominal contents pressing against the dependent hemidiaphragm, thereby restricting ventilation. Open non-dependent lung leads to variation in compliance and thus worsens ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch - thereby leading to hypoxemia.

Single-lung ventilation leads to a right-to-left intrapulmonary shunt as the nondependent lung continues to undergo perfusion with no ventilation, leading to a widened alveolar-to-arterial (A-a) oxygen gradient, which may contribute further to hypoxemia. Factors leading to decreased blood flow to the ventilated lung also lead to hypoxemia. Such factors include:

- Low Fio2 leads to hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in the dependent ventilated lung

- High mean airway pressures in the dependent ventilated lung

- Vasoconstrictor agents

- Intrinsic PEEP

Carbon dioxide elimination is usually unaffected in using single-lung ventilation with adequate maintenance of minute ventilation. Both lungs may be affected independently by single-lung ventilation. The ventilated-dependent lung is prone to ventilator-induced lung injury due to higher tidal volumes used. The nondependent nonventilated lung is prone to injury by surgical trauma and ischemia-reperfusion injuries. Considering these physiological changes in single-lung ventilation is vital to safely performing the anesthetic technique and airway management.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Single-lung ventilation is used to maintain adequate oxygenation, lung isolation, and lung protection. The challenges faced by an anesthesiologist in performing single-lung ventilation arise from a combination of lateral decubitus positioning, open pneumothorax, and the anesthetic technique.

The lateral decubitus position brings about physiological changes in ventilation-perfusion matching. This is subsequently altered under anesthesia by the effects of neuromuscular blockade, open thorax, hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, surgical retraction, and differential blood flow to the dependent and the nondependent lungs.

All interprofessional team members, including clinicians and nurses, must be very familiar with the parameters, procedures, and monitoring of patients receiving single-lung ventilation; this will yield optimal patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

References

Hickey SM, Giwa AO. Mechanical Ventilation. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969564]

Chiumello D, Formenti P, Bolgiaghi L, Mistraletti G, Gotti M, Vetrone F, Baisi A, Gattinoni L, Umbrello M. Body Position Alters Mechanical Power and Respiratory Mechanics During Thoracic Surgery. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2020 Feb:130(2):391-401. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004192. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31935205]

McGrath B, Tennuci C, Lee G. The History of One-Lung Anesthesia and the Double-Lumen Tube. Journal of anesthesia history. 2017 Jul:3(3):76-86. doi: 10.1016/j.janh.2017.05.002. Epub 2017 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 28842155]

Cohen E. Current Practice Issues in Thoracic Anesthesia. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2021 Dec 1:133(6):1520-1531. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005707. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34784334]

Hao D, Saddawi-Konefka D, Low S, Alfille P, Baker K. Placement of a Double-Lumen Endotracheal Tube. The New England journal of medicine. 2021 Oct 14:385(16):e52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm2026684. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34644474]

Bora V, Kritzmire SM, Arthur ME. Double-Lumen Endobronchial Tubes. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30570987]

Mehrotra M, D'Cruz JR, Arthur ME. Video-Assisted Thoracoscopy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422547]

Campos JH. An update on bronchial blockers during lung separation techniques in adults. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2003 Nov:97(5):1266-1274. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000085301.87286.59. Epub [PubMed PMID: 14570636]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVernick WJ, Woo JY. Anesthetic considerations during minimally invasive mitral valve surgery. Seminars in cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2012 Mar:16(1):11-24. doi: 10.1177/1089253211434591. Epub 2012 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 22361820]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim HY, Baek SH, Je HG, Kim TK, Kim HJ, Ahn JH, Park SJ. Comparison of the single-lumen endotracheal tube and double-lumen endobronchial tube used in minimally invasive cardiac surgery for the fast track protocol. Journal of thoracic disease. 2016 May:8(5):778-83. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.03.13. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27162650]

Clendenen N, Ahlgren B. Lung Isolation Techniques in Patients With Early-Stage or Long-Term Tracheostomy: A Clear Path Down a Tough Road. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2019 Feb:33(2):440-441. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.07.041. Epub 2018 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 30269887]

Mazzone PJ. Preoperative evaluation of the lung cancer resection candidate. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2010 Feb:4(1):97-113 [PubMed PMID: 20387296]

Ost DE, Jim Yeung SC, Tanoue LT, Gould MK. Clinical and organizational factors in the initial evaluation of patients with lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013 May:143(5 Suppl):e121S-e141S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2352. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23649435]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRawley M, Harris E, Pospishil L, Thompson JA, Falyar C. Assessing Provider Adherence To A Lung Protective Ventilation Protocol In Patients Undergoing Thoracic Surgery Using One-Lung Ventilation. AANA journal. 2022 Dec:90(6):439-445 [PubMed PMID: 36413189]

Boushy SF, Billig DM, North LB, Helgason AH. Clinical course related to preoperative and postoperative pulmonary function in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma. Chest. 1971 Apr:59(4):383-91 [PubMed PMID: 5573198]

Keagy BA, Lores ME, Starek PJ, Murray GF, Lucas CL, Wilcox BR. Elective pulmonary lobectomy: factors associated with morbidity and operative mortality. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1985 Oct:40(4):349-52 [PubMed PMID: 4051616]

Liptay MJ, Basu S, Hoaglin MC, Freedman N, Faber LP, Warren WH, Hammoud ZT, Kim AW. Diffusion lung capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is an independent prognostic factor for long-term survival after curative lung resection for cancer. Journal of surgical oncology. 2009 Dec 15:100(8):703-7. doi: 10.1002/jso.21407. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19798693]

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2000 May 4:342(18):1301-8 [PubMed PMID: 10793162]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSutherasan Y, Vargas M, Pelosi P. Protective mechanical ventilation in the non-injured lung: review and meta-analysis. Critical care (London, England). 2014 Mar 18:18(2):211. doi: 10.1186/cc13778. Epub 2014 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 24762100]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, Matthay MA, Morris A, Ancukiewicz M, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Jul 22:351(4):327-36 [PubMed PMID: 15269312]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNeedham DM, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Dinglas VD, Sevransky JE, Dennison Himmelfarb CR, Desai SV, Shanholtz C, Brower RG, Pronovost PJ. Lung protective mechanical ventilation and two year survival in patients with acute lung injury: prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2012 Apr 5:344():e2124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2124. Epub 2012 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 22491953]

Mosier JM, Hypes C, Joshi R, Whitmore S, Parthasarathy S, Cairns CB. Ventilator Strategies and Rescue Therapies for Management of Acute Respiratory Failure in the Emergency Department. Annals of emergency medicine. 2015 Nov:66(5):529-41. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.04.030. Epub 2015 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 26014437]

Weingart SD. Managing Initial Mechanical Ventilation in the Emergency Department. Annals of emergency medicine. 2016 Nov:68(5):614-617. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.04.059. Epub 2016 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 27289336]

Somhorst P, van der Zee P, Endeman H, Gommers D. PEEP-FiO(2) table versus EIT to titrate PEEP in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19-related ARDS. Critical care (London, England). 2022 Sep 12:26(1):272. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04135-5. Epub 2022 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 36096837]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiu Z, Liu X, Huang Y, Zhao J. Intraoperative mechanical ventilation strategies in patients undergoing one-lung ventilation: a meta-analysis. SpringerPlus. 2016:5(1):1251. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2867-0. Epub 2016 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 27536534]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence