Introduction

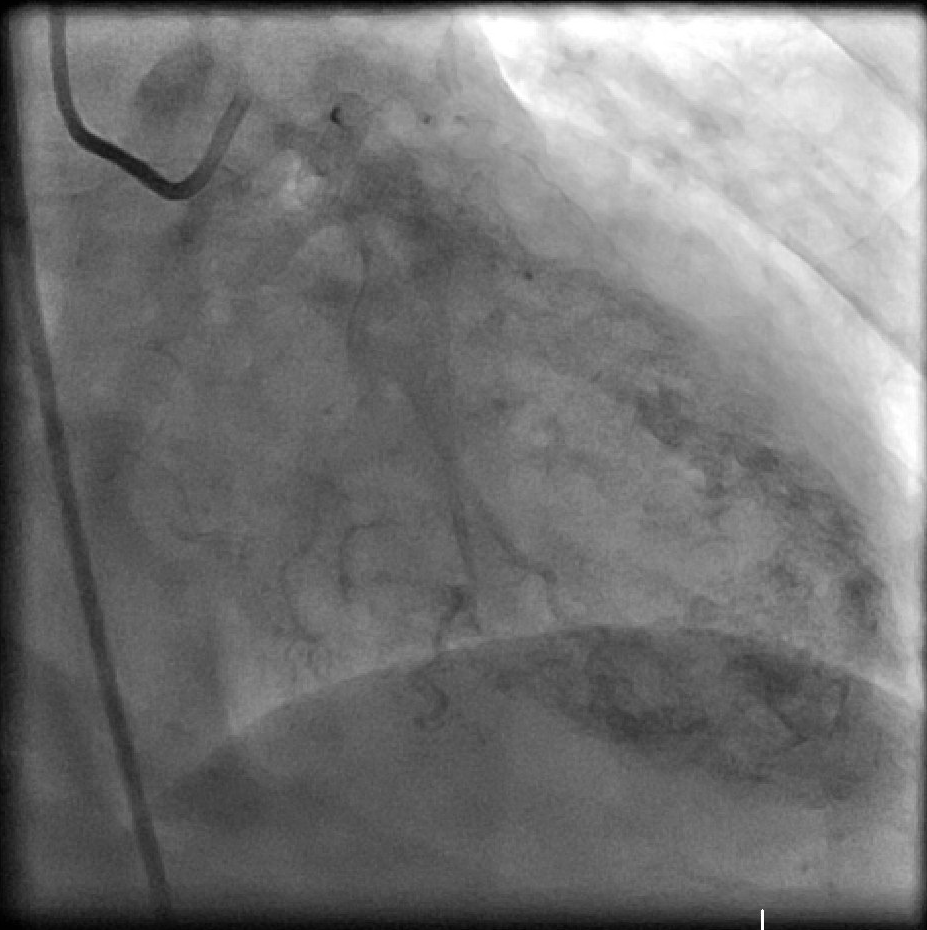

Coronary arteriovenous fistula (CAVF) is a rare form of congenital heart disease. However, it is the most common type of congenital coronary artery anomalies.[1][2].An arteriovenous fistula is an abnormal conduit between the artery and vein, typically bypassing the capillaries in between. When present between the coronary artery and cardiac chambers, it is called a coronary cameral fistula. See Images. Coronary Cameral Fistula, Left Coronary Artery, and Coronary Cameral Fistula, Right Coronary Artery. The fistula can also be present between a coronary artery and another adjacent vessel from pulmonary or systemic circulation. A patent fistula provides a low resistance flow, shunting the blood directly from an artery into a vein, cardiac chamber, or another low-pressure vessel like the pulmonary artery.[3] Patients with CAVF can develop symptoms at birth or a later age, depending on the type of fistula and the presence of collateral circulation. Studies have reported an association between ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death syndromes in young adults and athletes in certain types of coronary anomalies like the anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA).[4][5][6][7] Exertional dyspnea and angina pectoris from myocardial ischemia or endocardial fibrosis are the predominant symptoms in adults. Typically, these patients have extensive collateral formation.

Human coronary circulation comprises of two main epicardial coronary arteries. They arise from the coronary ostia located in the coronary sinus of Valsalva situated just above the aortic valve cusps. The aortic valve is tricuspid and consists of the right coronary cusp, left coronary cusp, and noncoronary cusp. The left coronary artery (LCA) originates from the left coronary sinus and branches into the left circumflex and the left anterior descending artery (LAD). The left circumflex artery supplies the anterolateral and posterolateral left ventricular walls. The left anterior descending artery supplies the anterior septum, the anterior free wall at the base and mid cavity level, apical septum, anterior wall, and apical cap. The right coronary artery (RCA) arises from the anterior aortic sinus or the right coronary sinus. It supplies the right atrium, right ventricle, sinoatrial (SA) node, and atrioventricular (AV) node. The posterior descending artery, a branch of RCA, provides blood supply to the inferior septum, the inferior free wall, and posterior left ventricular segments. The right coronary artery dominant variant is 80%.

The right coronary artery is the most common site of origin for CAVFs, found in approximately 50% of patients. Other sites include the left anterior descending artery in 35% to 40%, the left circumflex artery in 5% to 20%, and both coronary arteries in 5%.[8] Approximately 90% of the fistulas drain into the low-pressure venous circulation. The most common drainage sites are the right ventricle 41%, right atrium 26%, pulmonary artery 17%, coronary sinus 7%, left atrium 26%, left ventricle 3%, and superior vena cava 1%.[9]

A coronary arteriovenous fistula may lead to coronary artery dilatation due to increased flow, hyperkinetic pulmonary artery hypertension due to the large left to right shunt, congestive heart failure, myocardial ischemia from coronary steal phenomenon and thrombosis or aneurysm of fistula.[8]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The CAVF's can be congenital or acquired, 90% being congenital.[10] Persistence of embryonic sinusoids that perfuse primitive myocardium may lead to a fistulous connection between the coronary arteries and cardiac chambers (coronary cameral fistula).[11] Failure to the obliteration of embryonic connection between coronary arteries and other mediastinal vessels( bronchial, pericardial, or mediastinal arteries) or superior vena cava may result in the coronary arteriovenous fistula.[12] The acquired coronary arteriovenous fistulae, although rare, can result from cardiac trauma, procedures (coronary stent placement, coronary artery bypass grafting, chest irradiation), or cardiac disease (myocardial infarction, and coronary vasculitis).[13]

Epidemiology

Krause first reported the coronary arteriovenous fistula in 1865.[14] Prevalence is 0.002% in the general population and represents 0.4% of all cardiac malformation and constitutes nearly half of all coronary artery anomalies.[11][15][1] CAVF is incidentally noted in approximately 0.25% of the patients undergoing cardiac catheterization.[16] Most patients are older than 20 years and become symptomatic with increasing age.[14] It has been incidentally found in 0.06% of children undergoing echocardiography.[17] There is no race and sex predisposition.

Pathophysiology

In a healthy state, coronaries empty blood into the capillary bed of the myocardium. CAVF drains blood into the low-pressure vasculature like cardiac chambers, pulmonary artery, coronary sinus, and superior vena cava bypassing the capillaries. This vascular anatomy deprives the myocardium of blood supply leading to a coronary steal phenomenon resulting in cardiac ischemia. Left to right shunt leads to volume overload to the right heart leading to hyperkinetic pulmonary artery hypertension and right-sided congestive heart failure. The majority of patients with small fistula are asymptomatic. Patients with large fistula and left to right shunt with coronary steal phenomenon present with angina.[18]

History and Physical

A small coronary arteriovenous fistula that is not jeopardizing myocardial blood supply can remain asymptomatic. However, patients with a large fistula can present with ischemic symptoms like angina from coronary steal phenomenon. Left to right shunt may also cause right ventricular volume overload. They can manifest with features of right-sided heart failure like dyspnea, extremity swelling, orthopnea, and syncope. The clinician should suspect coronary arteriovenous fistula in patients with unexplained heart failure, with a history of chest trauma irradiation, myocardial infarction, or cardiac procedures. On examination, signs of congestive heart failure like raised jugular venous pressure, positive hepatojugular reflux, pedal edema, and pleural effusion can be present. Chest auscultation may reveal continuous murmur from increased flow in the large fistula and collaterals. A loud S2 and early diastolic murmur in the pulmonary area can point to pulmonary hypertension.

Evaluation

The electrocardiogram (ECG) may show features of left ventricular volume overload and ischemic changes.[19]

A chest x-ray can show cardiomegaly and pleural effusion due to congestive heart failure.[19]

2D echocardiography is useful to evaluate right and left ventricular size, mean pulmonary artery pressure in left to right shunt, and evaluation of regional or global left ventricular systolic function.[20]

Coronary angiography remains the primary diagnostic and therapeutic modality in the assessment of the fistula and embolization with coils and devices.[21]

Multidetector computed tomography is useful for the 3-dimensional anatomic evaluation for origin, patency, and termination of the CAVF.[22]

Magnetic resonance imaging is confirmatory, which shows detailed anatomy along with complications like myocardial fibrosis from ischemia.[23]

Treatment / Management

Spontaneous closure is reported in 1% to 2% of cases.[12] Small asymptomatic fistulas do not require treatment and are monitored for complications. American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines recommend closure of fistulas greater than 250 mm irrespective of symptoms, all symptomatic fistula regardless of size, including myocardial ischemia, arrhythmia, ventricular dysfunction, and endarteritis[class 1 recommendation].[24](A1)

The closure of the fistula can be achieved either from a percutaneous transcatheter approach or surgically via sternotomy.[12] Indications for endocardial or epicardial surgical ligation are: large fistula with high blood flow, tortuous and aneurysmal fistula, multiple communications and drainage sites, and need for a simultaneous distal bypass. Patients with proximal fistula origin, single drain site, non-tortuous fistula, simple and easily accessible fistula are suitable candidates for occlusion with coils, detachable balloons, vascular plugs, and duct occluders.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of coronary arteriovenous fistula includes conditions causing dilatation of coronary arteries and the presence of collateral vessels and continuous murmur.

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)

Patent ductus arteriosus is a condition that occurs due to the failure of the obliteration of the embryonic connection between the aorta and pulmonary artery. It can affect infants, children, and young adults. The symptoms are failure to thrive, poor feeding, shortness of breath, and easy fatiguability. On examination, bounding pulse, continuous murmur in the precordium, and signs of heart failure like pulmonary rales, raised JVD, and pedal edema can be found. The diagnosis is by Doppler echocardiography.[25]

Rupture of sinus of Valsalva aneurysm (SVA)

SVA is a rare congenital cardiac anomaly caused by the absence of media in the aortic wall behind the sinus of Valsalva. The aneurysm generally arises from the right coronary sinus. SVA commonly ruptures into the right-sided chambers leading to left to right shunt, rarely into the left atrium, left ventricle, pericardium, and pulmonary artery. Classic symptoms are acute onset of dyspnea and palpitations. Continuous murmur and sinus tachycardia are found on examination. Transthoracic echocardiography is diagnostic.[26]

Pulmonary arteriovenous fistula (PAVF)

A pulmonary arteriovenous fistula is an abnormal vascular connection between the pulmonary artery and veins, leading to a right-to-left shunt. The PAVF is also known as pulmonary arteriovenous aneurysms, cavernous angioma of the lung, and pulmonary telangiectasias.[27] It is generally asymptomatic and found incidentally on chest imaging. The common symptoms include hemoptysis, dyspnea, platypnea, and orthodexia (dyspnea induced by upright position and relieved when lying down). The physical exam can show cyanosis, clubbing, murmur, and a bruit. Stroke and brain abscess can occur from the paradoxical aneurysm and secondary polycythemia. Echocardiography with a bubble study can reveal a right-to-left shunt. A chest radiograph or a non-contrast computed tomography may show pulmonary nodules, representing the feeding pulmonary artery and a draining pulmonary vein. Pulmonary angiography is usually done on CT-identified lesions before embolotherapy.[28][29][30][28]

Aortopulmonary window (APW)

It is a rare congenital condition leading to a defect between the main pulmonary artery and proximal aorta with normally located semilunar valves. This condition is associated with other anomalies in 50% of the cases, like coarctation of the aorta, interrupted aortic arch, tetralogy of Fallot, and atrial septal defect. Small APW is usually asymptomatic. However, large APW presents with congestive heart failure. Symptoms are present in infancy, and 50% of patients die during the first year of life due to congestive heart failure without surgical correction. Transthoracic echocardiography, followed by cardiac catheterization, is diagnostic.[31]

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA).

The anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA), also known as Bland- White-Garland syndrome, is one of the coronary artery anomalies. In this entity, the left and right coronary arteries communicate via extensive collaterals, ultimately emptying blood from the right coronary artery into the pulmonary artery.

The right coronary artery becomes dilated, and the collaterals are visible on coronary angiogram and coronary computerized-tomography.[32]

Prolapse of the right coronary cusp with supracristal ventricular septal defect

In this condition, the right coronary cusp prolapses into the right ventricular outflow tract via a supracristal ventricular septal defect. This leads to symptoms of congestive heart failure. A pan-systolic murmur from ventricular septal defect, an early diastolic murmur from aortic regurgitation due to the right coronary cusp prolapse, can be present. Transthoracic echocardiography is diagnostic.[33]

Internal mammary to pulmonary artery fistula

It can be congenital, traumatic, or related to coronary artery bypass grafting using the left internal mammary artery. A continuous murmur is present on auscultation.[34]

Systemic arteriovenous fistula

Systemic arteriovenous fistula can be either traumatic (e.g., aortocaval fistula caused by a bullet trauma), iatrogenic (hemodialysis access), or congenital ( hepatic hemangioma and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasis). It produces high output cardiac failure and is one of the differential diagnoses of continuous murmur and dilated connection between artery and vein.[35]

Prognosis

Patients who undergo intervention have a good prognosis, and operative risks are low.[10] Prognosis depends on the severity of shunt and concomitant complications like congestive heart failure, endocarditis, and pulmonary hypertension.[10] Perioperative complications like the migration of the coil into the pulmonary artery, perforation of the vessel wall by the guidewire with thrombosis, and myocardial infarction contribute to early mortality and morbidity.[10] Studies have shown similar outcomes between open and transcatheter percutaneous closure procedures.[36] ACC/AHA recommend echocardiography every 3 to 5 years for asymptomatic patients with small fistula to evaluate for chamber enlargement.[24]

Complications

The possible complications of CAVFs are coronary artery dilatation, coronary aneurysm formation, atherosclerosis, infective endocarditis of fistula, endarteritis, obstruction, mural thrombosis, rupture, ischemia due to coronary steal phenomenon, arrhythmias, congestive heart failure with large shunts and hyperkinetic pulmonary artery hypertension with a large left to right shunt.[10]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Small CAVFs are asymptomatic, and patients should be advised for routine follow up echocardiography for monitoring. Prognosis is good with early intervention and should be encouraged for indicated patients as the outcome is excellent. Asymptomatic large fistulas require repair to avoid complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Coronary arteriovenous fistula can pose a diagnostic challenge. The patients may present with shortness of breath and chest pain and exhibit signs of heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. The condition can also mimic other diseases like patent ductus arteriosus. While the physical exam may reveal some clues, the underlying cause is difficult to know without proper diagnostic studies. The condition can be first encountered by a pediatrician, primary care physician, or a hospitalist. It is essential to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that include a general cardiologist, interventional cardiologist, radiologist, and cardiothoracic surgeon. The nurses are vital members of the interprofessional group as they will monitor the patient's vital signs and assist with the education of the patient and family. The pharmacist will ensure that the patient is on the right medications. The radiologist plays a vital role in determining the cause by CT or MRI.

Overall, to improve patient outcomes, prompt consultation with interprofessional group specialists and care coordination between physicians, nurses, and pharmacists is vital.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Fernandes ED, Kadivar H, Hallman GL, Reul GJ, Ott DA, Cooley DA. Congenital malformations of the coronary arteries: the Texas Heart Institute experience. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1992 Oct:54(4):732-40 [PubMed PMID: 1417232]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOlearchyk AS, Runk DM, Alavi M, Grosso MA. Congenital bilateral coronary-to-pulmonary artery fistulas. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1997 Jul:64(1):233-5 [PubMed PMID: 9236369]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWalløe L. Arterio-venous anastomoses in the human skin and their role in temperature control. Temperature (Austin, Tex.). 2016 Jan-Mar:3(1):92-103. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2015.1088502. Epub 2015 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 27227081]

Maron BJ, Shirani J, Poliac LC, Mathenge R, Roberts WC, Mueller FO. Sudden death in young competitive athletes. Clinical, demographic, and pathological profiles. JAMA. 1996 Jul 17:276(3):199-204 [PubMed PMID: 8667563]

Basso C, Maron BJ, Corrado D, Thiene G. Clinical profile of congenital coronary artery anomalies with origin from the wrong aortic sinus leading to sudden death in young competitive athletes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000 May:35(6):1493-501 [PubMed PMID: 10807452]

Cox ID, Bunce N, Fluck DS. Failed sudden cardiac death in a patient with an anomalous origin of the right coronary artery. Circulation. 2000 Sep 19:102(12):1461-2 [PubMed PMID: 10993868]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVan Camp SP, Bloor CM, Mueller FO, Cantu RC, Olson HG. Nontraumatic sports death in high school and college athletes. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 1995 May:27(5):641-7 [PubMed PMID: 7674867]

Gowda RM, Vasavada BC, Khan IA. Coronary artery fistulas: clinical and therapeutic considerations. International journal of cardiology. 2006 Feb 8:107(1):7-10 [PubMed PMID: 16125261]

Lin FC, Chang HJ, Chern MS, Wen MS, Yeh SJ, Wu D. Multiplane transesophageal echocardiography in the diagnosis of congenital coronary artery fistula. American heart journal. 1995 Dec:130(6):1236-44 [PubMed PMID: 7484775]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChalloumas D, Pericleous A, Dimitrakaki IA, Danelatos C, Dimitrakakis G. Coronary arteriovenous fistulae: a review. The International journal of angiology : official publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc. 2014 Mar:23(1):1-10. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1349162. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24940026]

Ogden JA. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries. The American journal of cardiology. 1970 Apr:25(4):474-9 [PubMed PMID: 5438244]

Yun G, Nam TH, Chun EJ. Coronary Artery Fistulas: Pathophysiology, Imaging Findings, and Management. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2018 May-Jun:38(3):688-703. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170158. Epub 2018 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 29601265]

Mangukia CV. Coronary artery fistula. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2012 Jun:93(6):2084-92. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.114. Epub 2012 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 22560322]

Ata Y, Turk T, Bicer M, Yalcin M, Ata F, Yavuz S. Coronary arteriovenous fistulas in the adults: natural history and management strategies. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2009 Nov 6:4():62. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-4-62. Epub 2009 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 19891792]

Dimitrakakis G, Von Oppell U, Luckraz H, Groves P. Surgical repair of triple coronary-pulmonary artery fistulae with associated atrial septal defect and aortic valve regurgitation. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2008 Oct:7(5):933-4. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.181388. Epub 2008 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 18544587]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDodge-Khatami A, Mavroudis C, Backer CL. Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project: anomalies of the coronary arteries. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2000 Apr:69(4 Suppl):S270-97 [PubMed PMID: 10798435]

Latson LA. Coronary artery fistulas: how to manage them. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2007 Jul 1:70(1):110-6 [PubMed PMID: 17420995]

Shiga Y, Tsuchiya Y, Yahiro E, Kodama S, Kotaki Y, Shimoji E, Fukuda N, Morito N, Urata M, Saito N, Niimura H, Mihara H, Yamanouchi Y, Urata H. Left main coronary trunk connecting into right atrium with an aneurysmal coronary artery fistula. International journal of cardiology. 2008 Jan 11:123(2):e28-30 [PubMed PMID: 17306898]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceQureshi SA. Coronary arterial fistulas. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2006 Dec 21:1():51 [PubMed PMID: 17184545]

Angelini P. Coronary artery anomalies--current clinical issues: definitions, classification, incidence, clinical relevance, and treatment guidelines. Texas Heart Institute journal. 2002:29(4):271-8 [PubMed PMID: 12484611]

Krishnamoorthy KM, Rao S. Transesophageal echocardiography for the diagnosis of coronary arteriovenous fistula. International journal of cardiology. 2004 Aug:96(2):281-3 [PubMed PMID: 15262046]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee CM, Leung TK, Wang HJ, Lee WH, Shen LK, Chen YY. Identification of a coronary-to-bronchial-artery communication with MDCT shows the diagnostic potential of this new technology: case report and review. Journal of thoracic imaging. 2007 Aug:22(3):274-6 [PubMed PMID: 17721342]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParga JR, Ikari NM, Bustamante LN, Rochitte CE, de Avila LF, Oliveira SA. Case report: MRI evaluation of congenital coronary artery fistulae. The British journal of radiology. 2004 Jun:77(918):508-11 [PubMed PMID: 15151973]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWarnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, Del Nido P, Fasules JW, Graham TP Jr, Hijazi ZM, Hunt SA, King ME, Landzberg MJ, Miner PD, Radford MJ, Walsh EP, Webb GD. ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: Executive Summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease). Circulation. 2008 Dec 2:118(23):2395-451. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190811. Epub 2008 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 18997168]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchneider DJ. The patent ductus arteriosus in term infants, children, and adults. Seminars in perinatology. 2012 Apr:36(2):146-53. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.025. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22414886]

Post MC, Braam RL, Groenemeijer BE, Nicastia D, Rensing BJ, Schepens MA. Rupture of right coronary sinus of Valsalva aneurysm into right ventricle. Netherlands heart journal : monthly journal of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology and the Netherlands Heart Foundation. 2010 Apr:18(4):209-11 [PubMed PMID: 20428420]

Ahn S, Han J, Kim HK, Kim TS. Pulmonary Arteriovenous Fistula: Clinical and Histologic Spectrum of Four Cases. Journal of pathology and translational medicine. 2016 Sep:50(5):390-3. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2016.04.18. Epub 2016 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 27156513]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCottin V, Chinet T, Lavolé A, Corre R, Marchand E, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Plauchu H, Cordier JF, Groupe d'Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies "Orphelines" Pulmonaires (GERM"O"P). Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: a series of 126 patients. Medicine. 2007 Jan:86(1):1-17. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31802f8da1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 17220751]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSanthirapala V, Chamali B, McKernan H, Tighe HC, Williams LC, Springett JT, Bellenberg HR, Whitaker AJ, Shovlin CL. Orthodeoxia and postural orthostatic tachycardia in patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: a prospective 8-year series. Thorax. 2014 Nov:69(11):1046-7. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205289. Epub 2014 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 24713588]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHanley M, Ahmed O, Chandra A, Gage KL, Gerhard-Herman MD, Ginsburg M, Gornik HL, Johnson PT, Oliva IB, Ptak T, Steigner ML, Strax R, Rybicki FJ, Dill KE. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Clinically Suspected Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformation. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2016 Jul:13(7):796-800. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.03.020. Epub 2016 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 27209598]

Ghaderian M. Aortopulmonary window in infants. Heart views : the official journal of the Gulf Heart Association. 2012 Jul:13(3):103-6. doi: 10.4103/1995-705X.102153. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23181179]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePfannschmidt J,Ruskowski H,de Vivie ER, [Bland-White-Garland syndrome. Clinical aspects, diagnosis, therapy]. Klinische Padiatrie. 1992 Sep-Oct; [PubMed PMID: 1405418]

Shaikh AH, Hanif B, Khan G, Hasan K. Supracristal ventricular septal defect with severe right coronary cusp prolapse. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2011 Jun:61(6):605-7 [PubMed PMID: 22204223]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePeter AA, Ferreira AC, Zelnick K, Sangosanya A, Chirinos J, de Marchena E. Internal mammary artery to pulmonary vasculature fistula--case series. International journal of cardiology. 2006 Mar 22:108(1):135-8 [PubMed PMID: 16516712]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSigler L, Gutiérrez-Carreño R, Martínez-López C, Lizola RI, Sánchez-Fabela C. Aortocava fistula: experience with five patients. Vascular surgery. 2001 May-Jun:35(3):207-12 [PubMed PMID: 11452347]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKiefer TL, Crowley AL, Jaggers J, Harrison JK. Coronary arteriovenous fistulae: the complexity of coronary artery-to-coronary sinus connections. Texas Heart Institute journal. 2012:39(2):218-22 [PubMed PMID: 22740735]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence