Introduction

The peritoneum is a continuous membrane that covers the abdominal and pelvic cavities. Anatomically, it has two layers that are, in and of themselves, continuous. One is the parietal peritoneum, which covers the inner surfaces of the abdominal and pelvic wall, and the other layer is the visceral peritoneum, which covers the abdominal organs and their suspending structures in the abdominopelvic cavity.[1] The greater omentum, a prominent peritoneal fold, also referred to as the gastrocolic ligament, has been referred to as a policeman of the abdomen, recognizing its role in containing inflammation and minimizing the spread of infection or local disease in the abdominopelvic cavity. This unique nature of the omentum puts it at risk of involvement with any abdominal malignancies through the spread of the local disease.

The term peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) generally refers to the metastatic involvement of the peritoneum. The name was first coined in 1931 by Sampson to thoroughly describe metastatic involvement of the peritoneal stromal surface by ovarian cancer cells.[2] Since then, it has referred to almost any peritoneal metastatic deposits. Metastatic cancer of the peritoneum is more common than a primary peritoneal malignancy. It often occurs with gastrointestinal or gynecological malignancies of advanced stages with locoregional involvement. Historically, the presence of metastatic deposits in the peritoneal cavity implied an incurable, fatal disease where curative surgical therapy was no longer a reasonable option. Newer surgical techniques and innovations in medical management strategies have dramatically changed the course of the disease over the past years. Effective treatment approaches have evolved, improving disease-free and overall survival[3].

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Peritoneal involvement is most common with cancers of the gastrointestinal (GI), reproductive, and genitourinary tracts. Ovarian, colon, and gastric cancers are by far the most common conditions presenting in advanced stages with peritoneal metastasis. Cancers involving other organs such as the pancreas, appendix, small intestine, endometrium, and prostate can also cause peritoneal metastasis, but such occur less frequently. While peritoneal carcinomatosis can arise from extra-abdominal primary malignancies, such cases are uncommon, and they account for approximately 10% of diagnosed cases of peritoneal metastasis.[4] Examples include breast cancer, lung cancer, and malignant melanoma. Ovarian cancer is the most common neoplastic disease-causing peritoneal metastasis in 46% of cases due to the ovaries' anatomic location and their close contact with the peritoneum as well as the embryological developmental continuity of ovarian epithelial cells with peritoneal mesothelial cells.[5][6]

- Colorectal cancer patients also contribute to a higher number of patients with peritoneal involvement due to the high incidence of these cancers overall. About 7% of cases develop synchronous peritoneal metastasis.[7]

- Approximately 9% of non-endocrinal pancreatic cancer cases present with PC.

- Gastric carcinoma tends to reach an advanced stage at first presentation, and 14% of such cases can have peritoneal metastasis.[8]

- A neuroendocrine tumor arising from the gastrointestinal tract (GI-NET) is a slow-growing neoplasm that can metastasize to the peritoneum. PC can occur in about 6% of GI-NET patients.[9] Its frequency increases with age.

- As described earlier, peritoneal carcinomatosis from extra-abdominal malignancy presents in only 10% of cases, where metastatic breast cancer (41%), lung cancer (21%), and malignant melanoma (9%) account for the majority of the cases.[4]

- Lung cancer is the primary cause of newly diagnosed cancers worldwide, accounting for over a million new cases per year. However, peritoneal carcinomatosis in lung cancer is rare and occurs in about 2.5 to 16% of autopsy results. Considering the scale of lung cancer rates globally, it could be the reason for a higher number of peritoneal carcinomatosis cases worldwide.[10]

- Sometimes, it is difficult to find the primary tumor site. In such cases, we have peritoneal carcinomatosis with an unknown primary (UP). About 3 to 5% of cases of peritoneal carcinomatosis are of unknown origin.[11]

Epidemiology

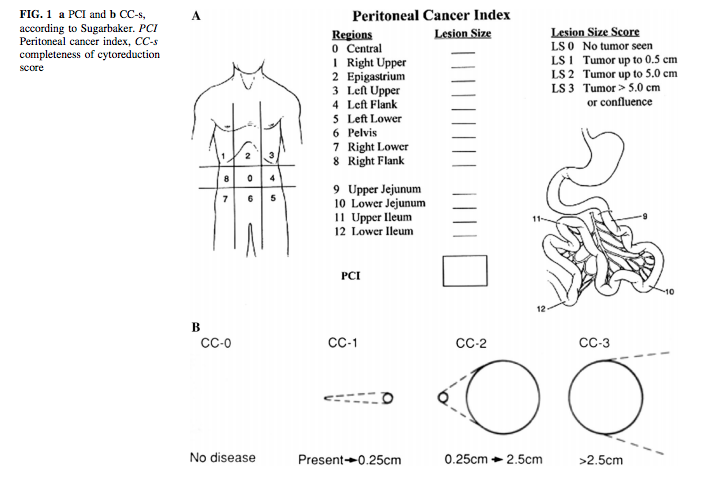

Peritoneal metastasis (PM) is a relatively rare diagnosis. Due to the lack of satisfactory preoperative detection methods and imaging studies, accurate incidence data is absent (see Figure. Peritoneal Cancer Index). Although registry data have suggested a rise in the overall incidence of peritoneal malignancy in the last two decades, advancements have been made in health technology to manage the condition. Peritoneal carcinomatosis is of primary peritoneal origin only 3% of the time; most often, it results from metastatic disease. One large population-based study from Ireland has shown that the annual incidence of peritoneal metastasis increased from 228 in 1994 to 402 in 2012. Females accounted for most cases, and 70% of patients were 60 or older at diagnosis.[12]

The incidence rate differs among the different types of primary cancers leading to peritoneal carcinomatosis. In the U.S., colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers with a higher rate of occurrence. Estimates of the incidence of peritoneal carcinomatosis in colorectal cancer are at around 5 to 8%, which accounts for 2 to 3 out of 100000 individuals per year.[13][7] Neuroendocrine tumors of the GI tract cause peritoneal metastasis in 1.6 per 1 million people per year in the U.S.[9]

Pathophysiology

Cancer cell metastasis is a complex phenomenon involving a multistage process and multidirectional spread. Dissemination, adhesion, invasion, and proliferation are significant steps in developing peritoneal metastasis from any primary source. Primary malignant cells can spread to distal sites through local invasion, lymphatics, or blood. In the case of peritoneal metastasis, malignant cells originating from primary abdominal organs usually spread through a transcoelomic mechanism. Peritoneal fluid cycles through the peritoneal cavity in a specific direction, which could spread the cancer cells in a particular manner. Extensive research has given more detailed knowledge about the pathophysiology of peritoneal metastasis. This complex process involves multilevel reactions among molecular and cellular components of the primary tumor site and the peritoneum. Peritoneal mesothelial cells provide adhesion to the invading cancer cells and stromal components, and endothelial cells help in proliferation.[14] Paget’s original “seed and soil” theory describes the pattern of peritoneal metastasis in cancers such as ovarian, colorectal, stomach, etc. It proposed that the organ-preference patterns of cancer metastasis are the product of favorable interactions between metastatic tumor cells (the "seed") and their organ microenvironment (the "soil"), which several research studies have extensively demonstrated.[15]

One theory describes that peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastrointestinal cancers can occur in two different ways: 1) Via transversal growth and 2) via intraperitoneal spread. Transversal growth means tumor cells can exfoliate from the primary tumor into the peritoneal cavity, also known as synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis. This variant usually occurs preoperatively. Intraperitoneal spread implies spread due to surgical trauma, where tumor cells get released unintentionally from transected lymph nodes or blood vessels or upon manipulation of the primary tumor during handling, referred to as metachronous peritoneal carcinomatosis. The most common dissemination of malignant cells in the peritoneum is due to spontaneous exfoliation. Leucocyte-associated adhesional molecules like CD44, selectins, and/or integrin have been identified for cancer cell adhesion. Peritoneal stroma is a rich source of all the necessary factors for proliferation.[16]

Hematogenous spread involving the peritoneal cavity can occur in patients with malignant melanoma, lung and breast cancer. In such cases, the embolic metastatic focus begins as a small nodule and eventually progresses. The lymphatic spread usually revolves around the ligaments and mesentery, and such dissemination can occur in non-Hodgkin lymphoma or neuroendocrine tumors (NET).

Biological research describes three types of peritoneal cancer spread, which is helpful to understand to guide surgical management:

- Random Proximal Distribution (RPD): Typically occurs in moderate and high-grade cancers in early implantation due to the adherence molecules on the cancer cells near the tumor area. Examples include adenocarcinoma and carcinoid of an appendix, non-mucinous colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, and serous ovarian cancer.

- Complete Redistribution (CRD): Here, there is no adhesion with the peritoneum near the primary tumor due to the low biological activity of the cancer cells. Examples are pseudomyxoma peritonei and diffuse malignant mesothelioma.

- Widespread Cancer Distribution (WCD): The presence of adherence molecules on the cancer cells and mucus production leads to the aggressive and widespread dissemination of cancer. Examples in this category include mucinous colorectal cancer, mucinous ovarian cancer, and cystadenocarcinoma of the appendix.

Understanding the spread pattern helps determine the best surgical approach: RPD treatment is best via selective peritonectomy of macroscopically involved regions. While CRD and WCD treatment should be with complete peritonectomy and extensive cytoreduction therapy.[17]

History and Physical

Patients with peritoneal metastasis usually present in the late stage of the disease. They typically present with symptoms and signs associated with their advanced primary cancer. Often, peritoneal carcinomatosis is an accidental finding during surgical exploration for primary tumor resection or other elective procedures. The two most important clinical findings related to peritoneal carcinomatosis have been ascites and bowel obstruction. However, they are found clinically in less than 50% of patients.[18][19] Similar to any other cancer, patients may complain of loss of appetite and organ-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal distension, weight loss, etc. Two main clinical features that could raise the suspicion for peritoneal metastasis include 1) the presence of malignant cells in ascitic fluid (28% to 30% of colorectal peritoneal metastasis patients), and 2) bowel obstruction (8% to 20% of patients with colorectal peritoneal metastasis.[20]

Given the non-specific clinical picture associated with patients with peritoneal metastasis, it is highly unpredictable and difficult to diagnose this condition just based on clinical presentation. However, whenever there is a finding suggesting the possibility of abdominal cancer, clinicians should keep a low threshold for considering the presence of advanced-stage disease, as evidenced by the presence of peritoneal metastasis, even when imaging does not readily show this. The peritoneum and any ascitic fluid can be examined during surgical exploration during a planned or emergent procedure.

Evaluation

Metastatic cancer of the peritoneum is often an incidental finding detected during surgical exploration or on diagnostic imaging with modalities like CT scan or MRI performed for other indications. A biopsy of detected tumors or lesions is a confirmatory test that identifies the type of cancer cells and differentiates them from primary peritoneal cancer. The primary objectives of the work-up and investigation modalities employed in cases of suspected peritoneal metastasis are the following:

- Early detection of possible peritoneal metastasis in a patient with recently diagnosed abdominal or pelvic malignancy and to rule out the presence of distant metastases in extra-abdominal areas, which becomes an absolute contraindication for surgery with curative intent.

- To determine the extent, size, and major organ involvement by metastatic cancer to decide the proper patient selection for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

- Early staging of the PC to help ascertain valuable information about potential outcomes and predict prognosis after treatment.

Cancerous lesions involving the peritoneum are sometimes visible with CT Scan, MRI, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography PET/CT. Each modality is important depending on the type of cancer and area of involvement. The peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) scoring system proposed by Dr. Sugarbacker provides a useful tool for better patient selection for surgery and a better understanding of prognosis and outcome (described in the management and staging section below). So, most imaging studies are employed for their diagnostic parameters based on how accurately they can contribute to the PCI score preoperatively.[21]

CT Scan: It can provide appropriate site-specific cancer involvement in the abdominal cavity. The crucial findings for peritoneal metastasis are focal or diffuse thickening of peritoneal folds, which could appear as sclerotic, nodular, reticular, reticulonodular, or large plaque-like structures. Sometimes, a large, thick layer of inhomogeneous density would be visible between the abdominal wall and bowel loops, sometimes called an “omental cake.” It is a neoplastic tissue layer. CT also detects macronodules and micronodules if they are lying at the surface of the liver or spleen. Ascites can also be detected if it is over 50 ml.[22] The sensitivity of computed tomography scans of the abdomen and pelvis for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer-related PM is 90% for cancer nodules larger than 5 cm but drops to less than 25% for lesions smaller than 5 cm.[23] CT scans used to detect peritoneal tumors for future management decisions were also found to have inter-observer differences among radiologists, and they are not considered the most reliable tools for the same.[24] Additionally, CT is inefficient in assessing small bowel lesions, which could underestimate the PCI score preoperatively. However, it is still a valid tool for achieving optimal cytoreduction in cases of ovarian metastasis with moderate accuracy.[25] Currently, abdominopelvic CT scanning is the first line of investigation for detecting peritoneal metastasis in the presence of any abdominal primary.

MRI: It is also one of the diagnostic tools for detecting peritoneal metastasis. However, it has not shown any significant superiority over CT scanning. One study demonstrated an advantage of MR over single-helical CT in detecting metastasis over the peritoneum, omentum, and bowel.[26] Combining MRI and CT has improved the preoperative estimation of PCI compared to only CT-determined PCI.[27] Diffuse-weighted MRI is used more for its diagnostic parameters, and one recently published study showed significant results. Whole-body diffuse weighted imagine-MRI (WB-DWI/MRI) was significantly better in the prediction of inoperability for peritoneal carcinomatosis than CT with sensitivity of 90.6%, specificity of 100%, PPV of 100%, and NPV of 90.3%. For CT alone, these values were 25.0, 92.9, 80.0, and 52.0%, respectively.[28]

PET Scan: A PET-CT scan is more useful than just a PET scan, as adding CT allows for better anatomic visualization. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography PET/CT is the preferred imaging that can detect the presence of cancer lesions based on the cells' glucose uptake. It can be falsely negative when cells do not show good glucose uptake. Thus, in cases where it is used for postoperative imaging, it would be better to document preoperative results for comparison to avoid false-negative results.[22] PET-CT provides better accuracy and NPV than MRI in identifying the exact localization and area of the peritoneal metastasis.[29] PET-CT adds good value to conventional imaging, mainly for monitoring response to the therapy, especially on long-term follow-up.[30]

Diagnostic Laparoscopy: Surgeons recommend preoperative use of diagnostic laparoscopy to assess the resectability of peritoneal tumor nodules before undergoing cytoreductive surgery (CRS). This approach is useful in patients whose previous imaging studies are insufficient in providing adequate information about the extent of disease involvement. However, it is sometimes not favored due to the difficulty related to trocar insertion and the fear of port-site tumor recurrence. But currently, many surgeons are advocating its important role in affirmative decision-making before actually going for laparotomy. In one study, it was found to have a positive predictive value of 83.3%. It also helped to avoid unnecessary laparotomy in 45% of the cases with no port-site recurrences or morbidity after 18 months.[31] Similarly, another study suggested detailed technical aspects of the diagnostic laparoscopy, with over 94% of confirmative findings using only two trocars and 99% for all cases.[22] Extensive studies would be needed to prove its routine practical use.

New Proposed Diagnostic Methods

Different surgeon groups have proposed new diagnostic techniques for the optimum detection of peritoneal carcinomatosis and a more accurate understanding of its extent and size before considering surgical exploration:

- The detection of ascitic CEA (carcinoma embryonic antigen) is useful for diagnosing colorectal cancer (CRC) with PM.[32]

- Extensive involvement of the small bowel by peritoneal carcinomatosis precludes the use of cytoreductive surgery. CT lacks sufficient accuracy in preoperatively detecting disease in the small intestine, which may subsequently impact the decision to offer CRS. One group of researchers demonstrated that CT-enteroclysis (CTE) is very useful in detecting small bowel/mesentery cancerous implants. It showed 92% sensitivity, 96% specificity, 97% PPV and 91% NPV.[33]

- Another group of investigators explored the use of single-incision flexible endoscopy (SIFE) for diagnostic staging before surgery, and they compared it to rigid endoscopy (SIRE). The major objective was to avoid trocar site metastasis by reducing the need for extra trocar usage. The study showed feasibility in 94% of cases with SIFE and demonstrated superiority to SIRE regarding technical exploration and outcomes. Future studies are needed to compare this with conventional laparoscopy.[34]

Treatment / Management

Recent advancements in surgical techniques and favorable outcomes related to targeted chemotherapy have encouraged the aggressive treatment of PC whenever feasible and accessible. Complete cytoreductive surgery (CRS) combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) and systemic chemotherapy has become the mainstay treatment for peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) originating from most gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts carcinomas. The efficacy of this treatment was validated in 2003 by a randomized clinical trial that compared CRS combined with HIPEC versus systemic chemotherapy alone (median survival: 22.3 vs. 12.6 months, P = 0.032).[35] Macroscopically complete CRS (CRS-R0) is a major prognostic factor, with 5-year survival rates as high as 45% compared to less than 10% when CRS is incomplete.[36] Dr. Sugarbaker changed the perception of peritoneal carcinomatosis from terminal cancer to a loco-regional disease and recommended an aggressive surgical approach with CRS, given the positive survival benefits. The first step in the management centers is the appropriate selection of patients for surgery.(A1)

Patient Selection

- Patient characteristics: age, comorbidities, general condition, and functional status. The objective is to determine the patient's fitness for the anticipated trauma of surgery and its perioperative impact.

- Exclude generalized metastatic disease: As pointed out in the diagnostic section, CT and/or MRI, or sometimes PET/CT, can be used to investigate potential distal metastases depending on the type of cancer. Possible sites to look for are the thorax, spine bones, brain, etc.

- The extent of the peritoneal disease:

CT/MRI is the primary investigation tool to determine the size, extent, and type of peritoneal lesions. The PCI scoring system described in Figure 1 is routinely used to determine the surgical resectability and possibly favorable prognosis. Diagnostic laparoscopy provides very accurate estimates for PCI, probable completeness of the cytoreduction (CC) index, and outcome assessment regarding disease-free survival, overall survival, and quality of life. The involvement of the small bowel impacts the PCI score and can suggest a bad prognosis. The following are the usual surgical sites used for preoperative determination of the extent of the disease for exclusion from CRS.[22]

- Massive mesenteric root infiltration is not amenable to complete cytoreduction

- Significant pancreatic capsule infiltration or pancreatic involvement requiring major resection is not feasibly or amenable to complete surgical cytoreduction

- More than one-third of small bowel length involvement requires resection

- Extensive hepatic metastasis

Some surgeons advocate using peritoneal surface disease severity score (PSDSS) for the early preoperative assessment of the prognosis based on the symptoms, PCI index, and primary tumor histology. However, extensive study results are needed to implement it in regular practice.[37](B2)

Cytoreductive Surgery (CRS) and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

Upon determining patient fitness for surgery with selection driven by feasibility criteria, CRS is commonly performed through an open abdominal wall incision approach along with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. This novel treatment option became a reality for surgeons through the extensive work of Dr. Sugarbacker[38] and his suggested surgical techniques. Cytoreductive surgery includes peritonectomy and individualized manual resection of the tumor lesions from different areas of the abdominal wall and mesentery. Peritonectomy now classifies as a curative treatment method for patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, with the latter viewed as the locoregional spread instead of systemic disease. The usual surgical intention for any cancer treatment is the removal of all cancer cells through en-block resections with clear margins. However, it is difficult to remove malignant cells completely for peritoneal carcinomatosis. The idea behind cytoreduction is to remove any macroscopic lesions completely, and the simultaneous use of HIPEC would potentially remove microscopic cancer lesions.[39][40] This technical approach has shown tremendous survival benefits along with disease-free survival and improved quality of life in patients. Currently, CRS combined with HIPEC is a first-line treatment for appendiceal and colorectal cancer-related PM.[41][42] It has also shown a promising role in ovarian, gastric, and neuroendocrine tumors.[43][8][44] (A1)

Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC)

This newer innovative therapeutic intervention has potential use in patients with extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis who may be deemed unresectable or unfit for surgery. The basis for aerosol chemotherapy is that the intraabdominal application of chemotherapeutic drugs under pressure could potentially enhance tissue penetration and increase distribution.[45] It has also been found to have superior benefits of drug delivery to tumor tissue with a significant effect on tumor regression than conventional intraperitoneal chemotherapy or systemic chemotherapy.[46] This treatment option is beneficial in patients with extraperitoneal metastases, and this method could work as an effective palliative treatment option. Further prospective trials are needed to determine its future role and regular use.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for peritoneal metastasis include the following:

- Primary peritoneal malignancy

- Peritoneal mesothelioma

- Peritoneal tuberculosis

- Peritonitis

Medical Oncology

HIPEC

The limited effectiveness of systemic chemotherapy for peritoneal tumors, mostly due to the poor tumor blood supply and poor penetration, impedes its use after CRS. Instead, intraperitoneal chemotherapy is a common option in combination with CRS, especially in the presence of PC. Hyperthermia adds a direct cytotoxic advantage.[47] The primary purpose of HIPEC is to eliminate potential micrometastasis that surgery cannot remove. Two main chemotherapeutic agents are used in current clinical practice: 1) oxaliplatin and 2) mitomycin C.[48] They are alkylating agents, non-cell cycle-dependent, with enhanced cytotoxicity under hyperthermia and maximal tissue penetration up to less than or equal to 2.5 mm.[49]

The practical role of this approach regarding additional survival benefits has shown variability. One multicenter Dutch randomized controlled trial showed significant improvement in disease-free survival and overall survival in patients treated with CRS+HIPEC compared to the surgery-only treated group for advanced ovarian disease.[50] Also, the first RCT study demonstrated better survival outcomes when treated with HIPEC. However, they also emphasized that complete achievement of cytoreduction is an important determinant given the exceptional 5-year survival of 45% with R1 resection.[36] While the French Prodige-7 trial questioned the actual benefit of HIPEC compared to systemic therapy regarding advanced colorectal cancer, the difference in results might be related to the differences in parameters used in HIPEC. Certain parameters that were found to have an impact on the efficacy of HIPEC are the type of chemotherapeutic drug used, its concentration, carrier solution, the volume of the perfusate, temp of the perfusate, treatment duration, delivery technique, and patient selection.[51] Surgeons performing HIPEC treatment in different countries showed variations in their delivery technique (open vs. closed) and perfusate temperature (varied 41 to 43 C). ASPSM (American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancy) has proposed the standardized use of HIPEC in treating PC from colorectal cancer origin. A consensus from surgeons resulted in the 7 HIPEC parameters.[52] The following are their suggested specifications:

- HIPEC Method: Closed.

- Drug: Mitomycin C

- Dosage: 40 mg

- The timing of drug delivery: 30 mg at time 0, 10 mg at 60 min.

- Volume of perfusate: 3 L

- Inflow temperature: 42 C

- Duration of perfusion: 90 min

Future studies, however, are needed to investigate the relative contribution or efficacy of each parameter. The proliferation of HIPEC treatment centers and ongoing prospective trials could possibly help standardize treatment and patient selection for optimal outcomes in the near future.

PIPAC

Another new therapeutic approach recently adopted in treating peritoneal carcinomatosis is pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC). This innovative approach shows safety and feasibility, along with systemic chemotherapy, in treating patients with PC and extraperitoneal metastases. It also showed less renal and hepato-toxicity, along with fewer side effects.[53] It is based on the assumption and related effectiveness evidence of ex-vivo and in vitro models that show that 1) intraabdominal application of chemotherapy under pressure enhances tumor drug uptake, 2) aerosolizing and spraying chemotherapy enhances the area of the peritoneal surface covered by the drug, and that this mechanical approach (3) results in improved anti-tumor efficacy.[54] The fundamental advantage of aerosol chemotherapy is laparoscopic delivery and less surgical trauma. It has also shown drug distribution and tissue penetration superiority over HIPEC and systemic chemotherapy.[46] Current clinical trials are underway. One registry-based study showed the possible and safe use of multiple PIPAC therapies with zero mortality and minimal morbidity. It has significantly improved ascites and tumor progression.[55] Available preliminary data suggest an enhanced quality of life and/or postponement in the deterioration of the quality of life in the context of end-stage disease. This treatment is a newly emerging palliative treatment option for patients with extensive advanced cancer.[54]

Staging

Gilly classification: This system is used mainly for prognostic evaluation.

- Stage 0: No macroscopic disease

- Stage 1: Malignant implants less than 5 mm in size and localized to one part of the abdomen

- Stage 2: Diffuse to the whole abdomen

- Stage 3: Implants 5mm to 2 cm

- Stage 4: Large malignant nodules - greater than 2 cm

PCI score: As described in the figure, PCI scoring is the staging method used preoperatively and intraoperatively for surgical patient selection, prognosis determination, and future outcome prediction. CC score: Completeness of Cytoreduction: Surgeons use this scoring system to assess surgical resection and look for prognostic benefits. They subdivide into the following score levels depending on the presence of carcinomatous lesions after surgery in any abdominal quadrant. CC 0 and CC 1 scores suggest better survival outcomes. Efforts remain directed at achieving complete cytoreduction whenever possible.

- CC 0 - no disease

- CC 1 - Present - less than 0.25 cm

- CC 2 - 0.25 to 2.5 cm

- CC 3 - greater than 2.5 cm

Prognosis

Quantitative prognostic indicators currently used for peritoneal carcinomatosis are the following: [21]

- Tumor histology

- Intraoperative assessment of the extent of carcinomatosis at the time of surgical exploration, which can be determined by different scoring systems as described earlier, and they include:

- Gilly staging

- PCI scoring system

- Staging by the Japanese cancer society for gastric cancer

- Dutch simplified peritoneal carcinomatosis index (SPCI)

- Completeness of cytoreduction (CC)

- Patient's clinical symptoms

The primary outcome parameters, such as overall survival, disease-free survival, and 5-year survival rate, depend on the type of primary cancer, the achievement of cytoreduction (based on CC scoring), HIPEC treatment, and/or the biological activity of the cancer. Peritoneal metastasis from an unknown primary tumor (UPT) has a poor prognosis, reaching as low as three months survival duration. Although specific histologic subtypes have shown favorable survival, efforts should focus on detecting and identifying the primary tumor, potentially increasing the prognostic benefits of treatment.[11]

Complications

Complications related to untreated/inoperable PC:[56]

- Refractory ascites

- Intestinal obstruction

- Gastrointestinal dysmotility

- Pulmonary thromboembolism

- Peritonitis

- Complications related to portal hypertension include upper GI bleed related to esophageal varices, splenomegaly, hepatic encephalopathy, and ascites

- Enteric fistula

Postoperative complications related to CRS include bleeding, infection, bowel obstruction, hemorrhage, or peritonitis. Complications related to HIPEC include: Oxaliplatin is used with dextrose solutions, so it could potentially contribute to postoperative acidosis and hyperglycemia; Mitomycin C can cause neutropenia in about one-third of patients and other GI side effects

Deterrence and Patient Education

Peritoneal metastasis is naturally a huge problem for patients. So, healthcare professionals should counsel them about the condition and refer them to a psychologist if needed. Moreover, third spacing leading to ascites should be countered with salt and water restriction.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Often, when patients learn of having peritoneal carcinomatosis, they become taken with fear and anxiety, losing hope for a cure. The evolution of surgical and medical management for peritoneal carcinomatosis has provided much-needed encouragement, better outcomes, and enhanced quality of life for some patients. Healthcare providers should become increasingly aware of the potential benefits of cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC when appropriately applied. They should encourage and arm newly diagnosed patients with available information and help arrange appropriate referrals to consider surgical treatment options, preferably in interprofessional oncologic settings when available. In the hope of the best possible outcomes, patients and their healthcare providers are encouraged not to underestimate general abdominal and bowel-related symptoms, especially when suggestive of intestinal obstruction, and to keep malignancy, including peritoneal carcinomatosis, on the differential diagnosis for early detection and treatment whenever possible.

The overall outlook for patients with PC is poor. Thus, it is essential to approach these cases in an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacy. A board-certified oncology pharmacist should work with the oncologist on agent selection and dosing and educate the patient on pain management and available options. Consult with pain services, a hospice nurse, and palliative care merits consideration early on in the treatment.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Blackburn SC, Stanton MP. Anatomy and physiology of the peritoneum. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 2014 Dec:23(6):326-30. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.06.002. Epub 2014 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 25459436]

Sampson JA. Implantation Peritoneal Carcinomatosis of Ovarian Origin. The American journal of pathology. 1931 Sep:7(5):423-444.39 [PubMed PMID: 19969977]

Klos D, Riško J, Stašek M, Loveček M, Hanuliak J, Skalický P, Lemstrová R, Mohelníková BD, Študentová H, Neoral Č, Melichar B. Current status of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy (HIPEC) in the multimodal treatment of peritoneal surface malignancies. Casopis lekaru ceskych. 2018 Dec 17:157(8):419-428 [PubMed PMID: 30754979]

Flanagan M, Solon J, Chang KH, Deady S, Moran B, Cahill R, Shields C, Mulsow J. Peritoneal metastases from extra-abdominal cancer - A population-based study. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2018 Nov:44(11):1811-1817. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.07.049. Epub 2018 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 30139510]

Lengyel E. Ovarian cancer development and metastasis. The American journal of pathology. 2010 Sep:177(3):1053-64. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100105. Epub 2010 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 20651229]

Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Quinn MA, Benedet JL, Creasman WT, Ngan HY, Pecorelli S, Beller U. Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2006 Nov:95 Suppl 1():S161-92 [PubMed PMID: 17161157]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceQuere P, Facy O, Manfredi S, Jooste V, Faivre J, Lepage C, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology, Management, and Survival of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis from Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2015 Aug:58(8):743-52. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000412. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26163953]

Gill RS, Al-Adra DP, Nagendran J, Campbell S, Shi X, Haase E, Schiller D. Treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: a systematic review of survival, mortality, and morbidity. Journal of surgical oncology. 2011 Nov 1:104(6):692-8. doi: 10.1002/jso.22017. Epub 2011 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 21713780]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMadani A, Thomassen I, van Gestel YRBM, van der Bilt JDW, Haak HR, de Hingh IHJT, Lemmens VEPP. Peritoneal Metastases from Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Incidence, Risk Factors and Prognosis. Annals of surgical oncology. 2017 Aug:24(8):2199-2205. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5734-x. Epub 2017 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 28204963]

Sereno M, Rodríguez-Esteban I, Gómez-Raposo C, Merino M, López-Gómez M, Zambrana F, Casado E. Lung cancer and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Oncology letters. 2013 Sep:6(3):705-708 [PubMed PMID: 24137394]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThomassen I, Verhoeven RH, van Gestel YR, van de Wouw AJ, Lemmens VE, de Hingh IH. Population-based incidence, treatment and survival of patients with peritoneal metastases of unknown origin. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2014 Jan:50(1):50-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.08.009. Epub 2013 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 24011935]

Solon JG, O'Neill M, Chang KH, Deady S, Cahill R, Moran B, Shields C, Mulsow J. An 18 year population-based study on site of origin and outcome of patients with peritoneal malignancy in Ireland. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2017 Oct:43(10):1924-1931. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.05.010. Epub 2017 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 28583791]

Klaver YL, Lemmens VE, Nienhuijs SW, Luyer MD, de Hingh IH. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: Incidence, prognosis and treatment options. World journal of gastroenterology. 2012 Oct 21:18(39):5489-94. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5489. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23112540]

Mikuła-Pietrasik J, Uruski P, Tykarski A, Książek K. The peritoneal "soil" for a cancerous "seed": a comprehensive review of the pathogenesis of intraperitoneal cancer metastases. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2018 Feb:75(3):509-525. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2663-1. Epub 2017 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 28956065]

Langley RR, Fidler IJ. The seed and soil hypothesis revisited--the role of tumor-stroma interactions in metastasis to different organs. International journal of cancer. 2011 Jun 1:128(11):2527-35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26031. Epub 2011 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 21365651]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTerzi C, Arslan NC, Canda AE. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of gastrointestinal tumors: where are we now? World journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Oct 21:20(39):14371-80. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14371. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25339824]

Kusamura S, Baratti D, Zaffaroni N, Villa R, Laterza B, Balestra MR, Deraco M. Pathophysiology and biology of peritoneal carcinomatosis. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2010 Jan 15:2(1):12-8. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i1.12. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21160812]

Chu DZ, Lang NP, Thompson C, Osteen PK, Westbrook KC. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in nongynecologic malignancy. A prospective study of prognostic factors. Cancer. 1989 Jan 15:63(2):364-7 [PubMed PMID: 2910444]

Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, Beaujard AC, Rivoire M, Baulieux J, Fontaumard E, Brachet A, Caillot JL, Faure JL, Porcheron J, Peix JL, François Y, Vignal J, Gilly FN. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer. 2000 Jan 15:88(2):358-63 [PubMed PMID: 10640968]

Jayne DG, Fook S, Loi C, Seow-Choen F. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. The British journal of surgery. 2002 Dec:89(12):1545-50 [PubMed PMID: 12445064]

Harmon RL, Sugarbaker PH. Prognostic indicators in peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastrointestinal cancer. International seminars in surgical oncology : ISSO. 2005 Feb 8:2(1):3 [PubMed PMID: 15701175]

Valle M, Federici O, Garofalo A. Patient selection for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, and role of laparoscopy in diagnosis, staging, and treatment. Surgical oncology clinics of North America. 2012 Oct:21(4):515-31. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2012.07.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23021713]

Archer AG, Sugarbaker PH, Jelinek JS. Radiology of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer treatment and research. 1996:82():263-88 [PubMed PMID: 8849956]

de Bree E, Koops W, Kröger R, van Ruth S, Witkamp AJ, Zoetmulder FA. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal or appendiceal origin: correlation of preoperative CT with intraoperative findings and evaluation of interobserver agreement. Journal of surgical oncology. 2004 May 1:86(2):64-73 [PubMed PMID: 15112247]

Ferrandina G, Sallustio G, Fagotti A, Vizzielli G, Paglia A, Cucci E, Margariti A, Aquilani L, Garganese G, Scambia G. Role of CT scan-based and clinical evaluation in the preoperative prediction of optimal cytoreduction in advanced ovarian cancer: a prospective trial. British journal of cancer. 2009 Oct 6:101(7):1066-73. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605292. Epub 2009 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 19738608]

Low RN, Semelka RC, Worawattanakul S, Alzate GD. Extrahepatic abdominal imaging in patients with malignancy: comparison of MR imaging and helical CT in 164 patients. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2000 Aug:12(2):269-77 [PubMed PMID: 10931590]

Dohan A, Hoeffel C, Soyer P, Jannot AS, Valette PJ, Thivolet A, Passot G, Glehen O, Rousset P. Evaluation of the peritoneal carcinomatosis index with CT and MRI. The British journal of surgery. 2017 Aug:104(9):1244-1249. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10527. Epub 2017 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 28376270]

Dresen RC, De Vuysere S, De Keyzer F, Van Cutsem E, Prenen H, Vanslembrouck R, De Hertogh G, Wolthuis A, D'Hoore A, Vandecaveye V. Whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI for operability assessment in patients with colorectal cancer and peritoneal metastases. Cancer imaging : the official publication of the International Cancer Imaging Society. 2019 Jan 7:19(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40644-018-0187-z. Epub 2019 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 30616608]

Klumpp BD, Schwenzer N, Aschoff P, Miller S, Kramer U, Claussen CD, Bruecher B, Koenigsrainer A, Pfannenberg C. Preoperative assessment of peritoneal carcinomatosis: intraindividual comparison of 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI. Abdominal imaging. 2013 Feb:38(1):64-71. doi: 10.1007/s00261-012-9881-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22476333]

De Gaetano AM, Calcagni ML, Rufini V, Valenza V, Giordano A, Bonomo L. Imaging of peritoneal carcinomatosis with FDG PET-CT: diagnostic patterns, case examples and pitfalls. Abdominal imaging. 2009 May-Jun:34(3):391-402. doi: 10.1007/s00261-008-9405-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18446399]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBravo R, Jafari MD, Pigazzi A. The Utility of Diagnostic Laparoscopy in Patients Being Evaluated for Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Peritoneal Chemotherapy. American journal of clinical oncology. 2018 Dec:41(12):1231-1234. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000463. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29782364]

Song SE, Choi P, Kim JH, Jung K, Kim SE, Moon W, Park MI, Park SJ. Diagnostic Value of Carcinoembryonic Antigen in Ascites for Colorectal Cancer with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. The Korean journal of gastroenterology = Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe chi. 2018 Jun 25:71(6):332-337. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2018.71.6.332. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29943560]

Courcoutsakis N, Tentes AA, Astrinakis E, Zezos P, Prassopoulos P. CT-Enteroclysis in the preoperative assessment of the small-bowel involvement in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, candidates for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Abdominal imaging. 2013 Feb:38(1):56-63. doi: 10.1007/s00261-012-9869-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22410875]

Najah H, Lo Dico R, Grienay M, Dohan A, Dray X, Pocard M. Single-incision flexible endoscopy (SIFE) for detection and staging of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Surgical endoscopy. 2016 Sep:30(9):3808-15. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4682-z. Epub 2015 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 26659231]

Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, van Sloothen GW, van Tinteren H, Boot H, Zoetmulder FA. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003 Oct 15:21(20):3737-43 [PubMed PMID: 14551293]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVerwaal VJ, Bruin S, Boot H, van Slooten G, van Tinteren H. 8-year follow-up of randomized trial: cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2008 Sep:15(9):2426-32. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9966-2. Epub 2008 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 18521686]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEsquivel J, Lowy AM, Markman M, Chua T, Pelz J, Baratti D, Baumgartner JM, Berri R, Bretcha-Boix P, Deraco M, Flores-Ayala G, Glehen O, Gomez-Portilla A, González-Moreno S, Goodman M, Halkia E, Kusamura S, Moller M, Passot G, Pocard M, Salti G, Sardi A, Senthil M, Spilioitis J, Torres-Melero J, Turaga K, Trout R. The American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies (ASPSM) Multiinstitution Evaluation of the Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score (PSDSS) in 1,013 Patients with Colorectal Cancer with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Annals of surgical oncology. 2014 Dec:21(13):4195-201. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3798-z. Epub 2014 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 24854493]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSugarbaker PH. Peritonectomy procedures. Surgical oncology clinics of North America. 2003 Jul:12(3):703-27, xiii [PubMed PMID: 14567026]

Sugarbaker PH. Evolution of cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis: are there treatment alternatives? American journal of surgery. 2011 Feb:201(2):157-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.04.010. Epub 2010 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 20870209]

Sugarbaker PH. Surgical responsibilities in the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Journal of surgical oncology. 2010 Jun 15:101(8):713-24. doi: 10.1002/jso.21484. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20512948]

Byrne RM, Gilbert EW, Dewey EN, Herzig DO, Lu KC, Billingsley KG, Deveney KE, Tsikitis VL. Who Undergoes Cytoreductive Surgery and Perioperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Appendiceal Cancer? An Analysis of the National Cancer Database. The Journal of surgical research. 2019 Jun:238():198-206. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.01.039. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 30772678]

Elias D, Gilly F, Boutitie F, Quenet F, Bereder JM, Mansvelt B, Lorimier G, Dubè P, Glehen O. Peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis treated with surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: retrospective analysis of 523 patients from a multicentric French study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Jan 1:28(1):63-8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9285. Epub 2009 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 19917863]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDeraco M, Kusamura S, Virzì S, Puccio F, Macrì A, Famulari C, Solazzo M, Bonomi S, Iusco DR, Baratti D. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy as upfront therapy for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: multi-institutional phase-II trial. Gynecologic oncology. 2011 Aug:122(2):215-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.05.004. Epub 2011 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 21665254]

Elias D, David A, Sourrouille I, Honoré C, Goéré D, Dumont F, Stoclin A, Baudin E. Neuroendocrine carcinomas: optimal surgery of peritoneal metastases (and associated intra-abdominal metastases). Surgery. 2014 Jan:155(1):5-12. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.05.030. Epub 2013 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 24084595]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGrass F, Vuagniaux A, Teixeira-Farinha H, Lehmann K, Demartines N, Hübner M. Systematic review of pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced peritoneal carcinomatosis. The British journal of surgery. 2017 May:104(6):669-678. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10521. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28407227]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHübner M, Teixeira H, Boussaha T, Cachemaille M, Lehmann K, Demartines N. [PIPAC--Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy. A novel treatment for peritoneal carcinomatosis]. Revue medicale suisse. 2015 Jun 17:11(479):1325-30 [PubMed PMID: 26255492]

Roti Roti JL. Cellular responses to hyperthermia (40-46 degrees C): cell killing and molecular events. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2008 Feb:24(1):3-15. doi: 10.1080/02656730701769841. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18214765]

Prada-Villaverde A, Esquivel J, Lowy AM, Markman M, Chua T, Pelz J, Baratti D, Baumgartner JM, Berri R, Bretcha-Boix P, Deraco M, Flores-Ayala G, Glehen O, Gomez-Portilla A, González-Moreno S, Goodman M, Halkia E, Kusamura S, Moller M, Passot G, Pocard M, Salti G, Sardi A, Senthil M, Spiliotis J, Torres-Melero J, Turaga K, Trout R. The American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies evaluation of HIPEC with Mitomycin C versus Oxaliplatin in 539 patients with colon cancer undergoing a complete cytoreductive surgery. Journal of surgical oncology. 2014 Dec:110(7):779-85. doi: 10.1002/jso.23728. Epub 2014 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 25088304]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDovern E, de Hingh IH, Verwaal VJ, van Driel WJ, Nienhuijs SW. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy added to the treatment of ovarian cancer. A review of achieved results and complications. European journal of gynaecological oncology. 2010:31(3):256-61 [PubMed PMID: 21077465]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencevan Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, Schagen van Leeuwen JH, Schreuder HWR, Hermans RHM, de Hingh IHJT, van der Velden J, Arts HJ, Massuger LFAG, Aalbers AGJ, Verwaal VJ, Kieffer JM, Van de Vijver KK, van Tinteren H, Aaronson NK, Sonke GS. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Jan 18:378(3):230-240. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708618. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29342393]

Helderman RFCPA, Löke DR, Kok HP, Oei AL, Tanis PJ, Franken NAPK, Crezee J. Variation in Clinical Application of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy: A Review. Cancers. 2019 Jan 11:11(1):. doi: 10.3390/cancers11010078. Epub 2019 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 30641919]

Turaga K, Levine E, Barone R, Sticca R, Petrelli N, Lambert L, Nash G, Morse M, Adbel-Misih R, Alexander HR, Attiyeh F, Bartlett D, Bastidas A, Blazer T, Chu Q, Chung K, Dominguez-Parra L, Espat NJ, Foster J, Fournier K, Garcia R, Goodman M, Hanna N, Harrison L, Hoefer R, Holtzman M, Kane J, Labow D, Li B, Lowy A, Mansfield P, Ong E, Pameijer C, Pingpank J, Quinones M, Royal R, Salti G, Sardi A, Shen P, Skitzki J, Spellman J, Stewart J, Esquivel J. Consensus guidelines from The American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies on standardizing the delivery of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in colorectal cancer patients in the United States. Annals of surgical oncology. 2014 May:21(5):1501-5. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3061-z. Epub 2013 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 23793364]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRobella M, Vaira M, De Simone M. Safety and feasibility of pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) associated with systemic chemotherapy: an innovative approach to treat peritoneal carcinomatosis. World journal of surgical oncology. 2016 Apr 29:14():128. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0892-7. Epub 2016 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 27125996]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTempfer CB. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy as an innovative approach to treat peritoneal carcinomatosis. Medical hypotheses. 2015 Oct:85(4):480-4. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2015.07.001. Epub 2015 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 26277656]

Kurtz F, Struller F, Horvath P, Solass W, Bösmüller H, Königsrainer A, Reymond MA. Feasibility, Safety, and Efficacy of Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) for Peritoneal Metastasis: A Registry Study. Gastroenterology research and practice. 2018:2018():2743985. doi: 10.1155/2018/2743985. Epub 2018 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 30473706]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLambert LA, Hendrix RJ. Palliative Management of Advanced Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Surgical oncology clinics of North America. 2018 Jul:27(3):585-602. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2018.02.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29935691]