Superior Ophthalmic Vein Cannulation for Carotid Cavernous Fistula

Superior Ophthalmic Vein Cannulation for Carotid Cavernous Fistula

Introduction

The superior ophthalmic vein (SOV) approach for embolization of carotid-cavernous fistulas (CCFs) was first described over 25 years ago.[1] CCFs are typically classified into 4 subtypes based on the etiology and nature of the lesion. Direct (Barrow type A) lesions involve an endothelial tear in the carotid artery itself, while indirect lesions (Barrow types B, C, or D) affect small branches of the internal or external carotid systems. Although 10% to 60% of CCFs may resolve spontaneously, and up to 30% of low-flow CCFs may improve with conservative management (carotid compression therapy), many progressive lesions require intervention.[2]

Direct lesions are treatable with endoarterial procedures, whereas indirect lesions are best managed with transvenous embolization, with the ipsilateral inferior petrosal sinus (IPS) being the preferred access route. Initial reports characterized case series where the SOV route was used when traditional access through the IPS was unsuccessful. The SOV is typically accessed through the facial-angular venous system; however, vessel stenosis, hypoplasia, or tortuosity can sometimes prevent safe transvenous access via this route. Surgical cutdown for direct cannulation of the SOV is a safe and effective option when other endovascular approaches have been exhausted. Although advances in endovascular access techniques have reduced the need for this method, direct cannulation of the SOV via surgical cutdown remains a valuable technique in the surgical armamentarium.[3]

SOV cannulation for CCF is a critical but challenging procedure in the management of vascular abnormalities affecting the cavernous sinus. CCF is an abnormal communication between the carotid artery and the cavernous sinus, leading to increased venous pressure and subsequent orbital congestion, proptosis, conjunctival chemosis, and vision-threatening complications. Endovascular treatment has revolutionized CCF management, with transvenous embolization being the preferred approach. Although the femoral and jugular routes are standard access points, anatomical variations and venous thrombosis may necessitate alternative routes, among which SOV cannulation is a key option.

The SOV is a vital orbital venous drainage pathway that connects the facial venous system to the cavernous sinus. However, its small caliber and anatomical variability make direct cannulation complex, requiring careful imaging guidance to ensure precise navigation and minimize complications. Despite these challenges, SOV access offers an invaluable route for embolization in cases where conventional venous access routes fail or are unavailable.[4]

SOV cannulation is particularly indicated when the traditional transfemoral or transjugular approach is unsuccessful due to venous occlusion, thrombosis, or anatomic anomalies. Indirect dural CCFs with preferential drainage through the ophthalmic venous system also warrant SOV access for optimal embolization. Additionally, patients with severe proptosis and orbital venous congestion may require urgent intervention through SOV cannulation to prevent irreversible visual impairment. The procedure relies on detailed anatomical knowledge of the SOV, which originates from the angular vein near the medial canthus and courses posteriorly into the superior orbital fissure. Anatomical variations, tortuosity, and the close proximity to surrounding structures, such as the optic nerve and extraocular muscles, make precise catheterization crucial. The vein is usually accessed percutaneously via a medial canthal approach, with real-time imaging guidance from modalities such as ultrasound and fluoroscopy to confirm its patency and location.[5]

The procedure for SOV cannulation begins with meticulous preparation, including the administration of local or general anesthesia and the creation of a sterile field. Ultrasound is used to visualize the vein, ensuring accurate entry and minimizing the risk of complications. A micropuncture needle is introduced through a small medial canthal incision, and a guidewire is carefully threaded into the vein. Once access is secured, a microcatheter is advanced through the SOV into the cavernous sinus, guided by fluoroscopy and angiography. The final step involves embolization using coils, liquid embolic agents such as Onyx, or detachable balloons to occlude the fistulous communication. Postprocedural imaging is performed to confirm successful closure, and careful hemostasis is achieved to prevent venous leakage.[6]

Despite its advantages, SOV cannulation presents several technical challenges. Small, tortuous, or thrombosed veins can complicate access, often requiring advanced imaging techniques or alternative surgical exposure. The fragility of the SOV increases the risk of vein rupture and orbital hemorrhage, and improper needle placement may cause inadvertent arterial puncture or optic nerve injury. Incomplete embolization is another concern, as partial occlusion of the fistula can lead to symptom recurrence, necessitating repeat interventions. Infection and thrombophlebitis are additional risks, making postprocedural monitoring essential to ensure patient safety.[7]

Advancements in imaging, catheter technology, and minimally invasive techniques are continuously refining the approach to SOV cannulation for CCF treatment. Endoscopic-assisted visualization improves procedural accuracy, while robotic-assisted navigation enhances precision in catheter placement. The development of bioabsorbable embolic agents may reduce long-term complications, and artificial intelligence-assisted imaging analysis can optimize procedural planning, further improving success rates. These innovations are poised to make SOV cannulation safer and more effective, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes.[8][9][10]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The SOV is crucial in orbital venous drainage and is an important access route for interventional procedures in managing CCF. A thorough understanding of its complex anatomy and physiological function is essential for successful cannulation and embolization of a CCF. The SOV is closely linked to the cavernous sinus, the orbital venous system, and critical neurovascular structures, making its precise localization and catheterization a technically challenging procedure.[11]

A thorough understanding of orbital anatomy is essential to prevent damage to key structures within the orbit, particularly once the orbital fat pad is exposed. The SOV forms at the junction of the supraorbital vein (SPOV), angular vein, and supratrochlear vein in the superomedial orbit. The SOV is consistently found approximately 6 mm above the superior sulcus of the eyelid nasally. The SOV can also be identified by tracing the SPOV into the orbit, as the SPOV may be found within the supraorbital notch when present.[12]

As the SOV courses posteriorly and laterally alongside the ophthalmic artery, which lies posterior and lateral to the superior oblique, it receives drainage from several superior orbital structures, including the ethmoid veins, central retinal vein, muscular veins, and superior vortex veins. The SOV crosses the anterior portion of the optic nerve before passing through the superior orbital fissure, where it ultimately drains into the cavernous sinus. Notably, the SOV is also known to run directly beneath the superior rectus muscle in the superomedial quadrant of the periorbital cone, serving as a useful landmark when the vessel is not hypertrophied outside the deep orbit.[2] Anastomosis with the inferior ophthalmic vein is variable.

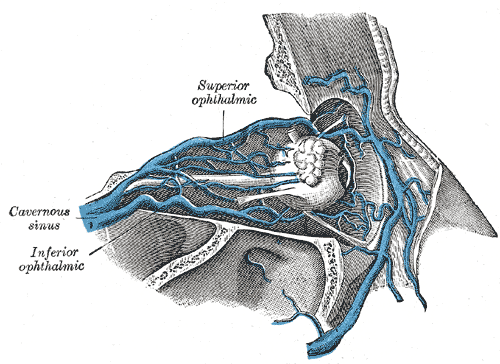

Anatomy of the Superior Ophthalmic Vein

The SOV originates from the angular vein near the medial canthus of the eye and courses posteriorly through the orbit. As the primary venous drainage channel of the orbit, it collects blood from the anterior and posterior orbital veins before emptying into the cavernous sinus via the superior orbital fissure (see Image. Superior Ophthalmic Vein, Inferior Ophthalmic Vein, and Cavernous Sinus). The SOV runs in close proximity to the optic nerve (CN II), oculomotor nerve (CN III), and branches of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V1), increasing the risk of iatrogenic injury during surgical or interventional procedures.

The tributaries of the SOV include:

- Angular vein: This vein forms the anterior connection with the facial venous system.

- Central retinal vein: This vein contributes to retinal venous outflow.

- Vorticose veins: These veins drain the choroidal circulation.

- Lacrimal and muscular veins: These veins drain the lacrimal gland and extraocular muscles.[12]

The valveless nature of the orbital venous system allows bidirectional blood flow, which is a key factor in the pathophysiology of CCF. This feature enables retrograde arterialized blood flow into the orbit, resulting in venous congestion, proptosis, and chemosis in patients with high-flow fistulas.[13]

Physiology of the Superior Ophthalmic Vein

The primary physiological function of the SOV is to maintain orbital venous drainage by linking the anterior facial venous system with the posterior cavernous sinus. Under normal conditions, venous blood flows in an anteroposterior direction toward the cavernous sinus. However, in CCFs, arteriovenous shunting causes retrograde venous drainage, leading to increased venous pressure. This results in the characteristic orbital manifestations of pulsatile proptosis, conjunctival chemosis, and elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). Chronic venous congestion may cause optic nerve compression, ischemic retinopathy, and secondary glaucoma if left untreated. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eye Ophthalmic Vein," for more information.

Importance of Superior Ophthalmic Vein Cannulation in Carotid-Cavernous Fistulas

In patients with CCF, embolization is the primary treatment to occlude the arteriovenous communication and restore normal venous drainage. When traditional transvenous routes, such as the IPS or transfemoral approach, are inaccessible due to thrombosis or anatomical variations, the SOV offers a viable alternative route for endovascular access.

The technical considerations for SOV cannulation include:

- Percutaneous access through the medial canthus, guided by ultrasound and fluoroscopy.

- Use of a micropuncture needle, followed by guidewire and microcatheter insertion.

- Navigation through the superior orbital fissure into the cavernous sinus for embolization.

- Careful avoidance of critical structures, such as the optic nerve, extraocular muscles, and ophthalmic artery, to minimize the risk of iatrogenic complications.[14]

Challenges and Risks

Cannulation of the SOV presents several challenges due to its small diameter, anatomical variability, and fragility. The associated risks include:

- Venous rupture, which can lead to orbital hemorrhage.

- Misplacement of the catheter, potentially causing optic nerve injury or arterial puncture.

- Incomplete embolization, which may result in residual arteriovenous shunting and symptom recurrence.

- Thrombophlebitis and infection, which necessitate careful postprocedural monitoring.

Understanding the anatomy and physiology of the SOV is crucial for safe and effective cannulation in CCF treatment. As a critical venous pathway for orbital drainage, its valveless structure significantly contributes to CCF pathophysiology. When conventional venous access routes are unavailable, SOV cannulation serves as a viable alternative for embolization. Meticulous anatomical knowledge and advanced imaging guidance are required to minimize risks and ensure successful outcomes.[15]

Indications

Direct cannulation of the SOV is a viable approach for endovascular treatment of indirect CCFs. Common signs and symptoms include pulsatile visual defects, headache, ocular and orbital pain, diplopia, conjunctival chemosis, proptosis, and orbital bruits. A standard association is congestion of the IPS and arterialization of the ophthalmic and orbital veins. The SOV can be used for transvenous access to cavernous sinus lesions when other approaches are anatomically unavailable or have been exhausted.

The aberrant anatomy of IPS, including excessive tortuosity or discontinuity with the proximal jugular system, may render this approach impossible. Access to the SOV through the angular and facial veins is a commonly used approach. However, the small vessel caliber and sharp angulation can present technical challenges. Direct cannulation of the SOV remains a viable alternative when arterial access is inadequate.[16] The decision to perform SOV cannulation depends on clinical presentation, anatomical feasibility, and procedural factors to ensure effective management and optimal patient outcomes. Below are the specific indications for using this technique.[17]

Failed or Inaccessible Inferior Petrosal Sinus Approach

The IPS is the preferred transvenous route for embolization of direct (high-flow) and indirect (low-flow) CCFs. However, anatomical variations, thrombosis, or stenosis may render this route non-navigable. SOV cannulation provides an alternative access to the cavernous sinus in such cases.

Factors that may necessitate SOV cannulation include:

- Thrombosis of the IPS due to chronic venous congestion.

- Congenital absence or hypoplasia of the IPS.

- Sinus occlusion due to prior surgical interventions or radiation.

- Failed transvenous access attempts due to tortuosity or obstruction.[18]

Orbital Venous Congestion and Elevated Intraocular Pressure

Patients with CCF often present with proptosis, chemosis, and elevated IOP due to arterialized retrograde venous flow into the orbit. When conservative management or conventional approaches are ineffective, direct SOV access enables targeted embolization, reducing venous hypertension and alleviating symptoms.

Indications for SOV access include:

- Severe pulsatile proptosis with corneal exposure.

- Resistant secondary glaucoma due to persistently elevated episcleral venous pressure.

- Progressive optic neuropathy due to chronic venous stasis.

- Orbital congestion refractory to medical therapy (eg, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and topical beta-blockers).[19]

Indirect (Dural) Carotid-Cavernous Fistulas Refractory to Conservative Treatment

Dural CCFs, commonly observed in older patients or following trauma, may resolve spontaneously. However, when persistent, they necessitate intervention. SOV access is indicated in the following scenarios:

- Persistent cortical venous reflux with risk of hemorrhage.

- Non-resolving orbital symptoms despite observation.

- Failed transarterial or transvenous approaches.

- Progressive vision deterioration despite conservative management.[20]

Direct (High-Flow) Traumatic Carotid-Cavernous Fistulas with Rapid Orbital Decompensation

Trauma-induced direct CCFs, often resulting from basilar skull fractures or penetrating injuries, can cause rapid orbital and cerebral deterioration. SOV cannulation is indicated in the following situations:

- High-flow CCFs with worsening venous hypertension.

- Acute visual compromise due to optic nerve compression.

- Severe venous outflow obstruction causing hemorrhagic complications.

- Urgent need for embolization when traditional routes fail.[21]

Alternative Route in Complex Vascular Anatomy

The SOV provides the most direct access to the cavernous sinus in specific anatomical scenarios, which is particularly relevant in circumstances as follows:

- Angiographic studies show favorable SOV dilation.

- IPS and facial venous connections are underdeveloped or absent.

- A controlled embolization strategy is required to prevent non-target occlusion.[22]

Recurrence After Previous Embolization

Recurrent CCFs following previous embolization, surgery, or spontaneous thrombosis may require repeat intervention. If initial transvenous routes become compromised, the SOV may serve as a reentry pathway for retreatment.

- Persistent arterialized flow detected on follow-up angiography.

- Incomplete fistula closure with residual venous drainage into orbital structures.

- New-onset orbital symptoms despite previous embolization success.

SOV cannulation is technically challenging but highly effective in cases where traditional transvenous routes are inaccessible or fail. This provides direct access to the cavernous sinus, allowing for precise embolization and symptomatic relief for patients with high-flow direct CCFs, refractory dural CCFs, and severe orbital venous congestion. A multidisciplinary approach, incorporating advanced imaging guidance and expert interventional techniques, is essential for maximizing success and minimizing complications in these complex cases.[23]

Contraindications

Conservative management resolves symptoms in many cases, so a thorough assessment of symptomology in the immediate preoperative period is crucial to avoid unnecessary intervention. If thrombosis of the SOV is observed intraoperatively, additional intervention may not be necessary. Patients with suspected direct or mixed CCFs require endoarterial treatment and should not be managed solely with transvenous embolization.

SOV cannulation is a crucial access route for embolizing CCF, especially when conventional transvenous pathways, such as the IPS, are inaccessible. However, despite its effectiveness, SOV cannulation is technically complex and carries potential risks, making it unsuitable in certain situations. Below is a detailed overview of the contraindications for SOV cannulation in the management of CCF. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Deep Venous Thrombosis Prophylaxis," for more information.

Absolute Contraindications

Absolute contraindications include conditions where SOV cannulation presents a significant risk to the patient and should be strictly avoided.

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis or extensive venous occlusion

- Rationale: Patients with cavernous sinus thrombosis or extensive venous occlusion have poor venous outflow, rendering SOV access ineffective. A thrombus can obstruct catheter advancement, increasing procedural failure and complications.

- Risks: Attempting SOV cannulation in thrombosed cases can lead to venous rupture, embolic complications, or worsening orbital venous congestion.

- Alternatives: Transarterial embolization or direct cavernous sinus puncture may be considered. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis," for more information.

- Orbital cellulitis or active ocular infection

- Rationale: Any active infection or inflammation within the orbit significantly increases the risk of septic embolism and orbital complications.

- Risk: Infection can spread along the venous system to the cavernous sinus, potentially causing septic thrombophlebitis or intracranial abscess formation.

- Alternatives: The infection should be treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics and drainage before any intervention. Once resolved, alternative vascular access should be considered. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Orbital Cellulitis," for more information.

- Severe proptosis with orbital compartment syndrome

- Rationale: In patients with severe proptosis, the SOV may be excessively stretched and tortuous, complicating catheterization and increasing the risk of iatrogenic rupture.

- Risk: Cannulating a tense, engorged vein can result in venous extravasation, hematoma formation, and worsening orbital pressure, potentially exacerbating vision loss.

- Alternatives: Lateral orbitotomy or transarterial embolization may offer safer alternatives in these cases.[24]

- Severe coagulopathy or anticoagulation therapy

- Rationale: Coagulopathy (eg, thrombocytopenia or hemophilia) or anticoagulation therapy (eg, warfarin, heparin, and direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs]) significantly increases bleeding risk.

- Risk: Uncontrolled hemorrhage from the orbital venous system may result in a retrobulbar hematoma, potentially leading to sight-threatening orbital compartment syndrome.

- Alternatives: Coagulation parameters should be optimized before intervention. If coagulopathy cannot be corrected, alternative access routes should be considered.[25]

- Acute ischemic stroke or intracranial hemorrhage

- Rationale: Patients with recent stroke or intracranial hemorrhage may have altered intracranial dynamics, increasing the risk of secondary hemorrhagic transformation during the procedure.

- Risk: SOV cannulation requires anticoagulation and catheter manipulation, which may worsen ongoing hemorrhagic pathology or trigger rebleeding.

- Alternatives: Intervention should be delayed until the acute event stabilizes, followed by an assessment of the safety of alternative access routes.[26]

Relative Contraindications

Relative contraindications refer to situations where SOV cannulation is technically possible but requires a careful risk-benefit evaluation.

- Small or absent superior ophthalmic vein

- Rationale: A hypoplastic or absent SOV may make cannulation technically difficult or unfeasible.

- Risk: Attempting to catheterize in a small or fragile vein increases the likelihood of venous injury, thrombosis, or failed access.

- Alternatives: A Doppler ultrasound assessment may be considered before the intervention, or an alternate venous route, such as the facial vein, angular vein, or transarterial access, can be used.[27]

- Previous orbital surgery or trauma

- Rationale: Prior orbital surgeries (eg, decompression and tumor excision) or traumatic injuries can cause fibrosis, scarring, or anatomical distortion, complicating SOV access.

- Risk: Challenges in catheter advancement, inadvertent arterial puncture, or iatrogenic damage to orbital structures.

- Alternatives: Preprocedural imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can be used to assess venous anatomy and the feasibility of alternative approaches.[28]

- Unstable cardiopulmonary status

- Rationale: Patients with severe cardiopulmonary conditions (e.g., advanced heart failure, severe pulmonary hypertension, or unstable arrhythmias) may not tolerate the hemodynamic changes associated with SOV manipulation.

- Risk: Hemodynamic instability, hypoxia, or arrhythmias during prolonged procedures under sedation or anesthesia.

- Alternatives: Cardiopulmonary status should be optimized before the procedure, and alternative vascular approaches should be considered.[29]

- Advanced glaucoma with severe optic nerve damage

- Rationale: In cases of advanced glaucomatous optic neuropathy, temporary venous congestion from SOV cannulation may worsen optic nerve damage.

- Risk: Progression of visual field loss or acute ischemic damage to the optic nerve.

- Alternatives: IOP should be closely monitored, and alternative access routes that minimize orbital congestion should be considered.[30]

- Inadequate imaging or poor patient cooperation

- Rationale: SOV cannulation requires precise fluoroscopic or ultrasound guidance, which may be challenging in patients with motion artifacts or inadequate anatomical visualization.

- Risk: Increased likelihood of procedural failure, vessel injury, or non-target embolization.

- Alternatives: Sedation techniques or consideration of alternative transarterial approaches.[31]

Procedural Challenges and Precautionary Considerations

Even in borderline cases, the below considerations should be carefully assessed before attempting SOV cannulation.

- Assessment of orbital venous drainage patterns: Preprocedural imaging (eg, venography and CT/MR angiography) should be performed to confirm patent venous outflow and ensure successful catheter navigation.

- Use of real-time imaging guidance: Fluoroscopy and ultrasound should be used to improve the accuracy and reduce the risk of complications.

- Preparation for hemostasis management: The preparation of hemostatic agents, vessel closure devices, and emergency surgical intervention should be in place for potential bleeding complications.

- Early consideration of alternative approaches: If SOV cannulation proves challenging, other routes should be explored, such as direct cavernous sinus puncture, transarterial embolization, or endovascular approaches.[11]

SOV cannulation is a highly specialized technique and a valuable alternative for treating CCF. However, specific anatomical, physiological, and pathological factors can make it unsafe or technically unfeasible. Absolute contraindications, such as cavernous sinus thrombosis, orbital cellulitis, severe coagulopathy, and orbital compartment syndrome, render the procedure too high-risk to attempt. Relative contraindications, including small SOV, prior orbital surgery, unstable cardiopulmonary status, or advanced glaucoma, require individualized risk-benefit assessment before proceeding. Careful patient selection, preprocedural imaging, and contingency planning are essential to optimize outcomes and minimize complications in this complex, high-stakes intervention.[27]

Equipment

Standard microsurgical and endovascular equipment are essential for ensuring precision, safety, and efficacy during this procedure. This procedure is typically performed in the endovascular suite with appropriate anesthesia support. A surgical headlight, along with the appropriate orbital surgical instruments, is essential for proper orbital exposure. This includes Sewell retractors, ribbon retractors, long bayonet forceps, and bipolar cautery forceps, which provide easy access to any bleeders deep within the orbit. Neurosurgical cottonoids are helpful for separating fat from vessels. Muscle hooks assist in gently lifting the SOV while ligation bands or sutures are applied. An experienced assistant is invaluable, as the surgeon will have limited mobility due to the radiology equipment.[11][27]

Imaging and Navigation Equipment

Successful SOV cannulation relies on real-time visualization for accurate vascular access and catheter guidance.

- Digital subtraction angiography: Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is a high-resolution imaging modality used to visualize venous anatomy and confirm fistula characteristics.

- Fluoroscopy with road-mapping feature: This allows real-time tracking of catheter and guidewire movement to facilitate safe SOV navigation.

- Ultrasound (high-frequency probe, 7-15 MHz): This imaging is useful for identifying the SOV, particularly in cases where fluoroscopy does not provide sufficient localization.

- 3-Dimensional (3D) rotational angiography (optional): This technique enhances visualization of the cavernous sinus and ophthalmic veins, aiding in the identification of complex anatomical variations.

- Microscope or surgical Loupes (optional): This provides enhanced magnification for improved visualization during percutaneous orbital venous access.[32]

Vascular Access and Cannulation Equipment

Selecting appropriate venous access tools is essential for precise and atraumatic SOV cannulation.

- Micro-access kit (21-22G access needle): This is used for the initial puncture of the SOV.

- Micropuncture introducer sheath (4F-5F, short-length): This sheath facilitates smooth catheter entry and stabilizes access during embolization.

- Guidewires (0.014–0.018 in, hydrophilic-coated): This assists in advancing the catheter into the SOV while minimizing vessel trauma.

- Angled or straight microcatheters (1.5-2.8 F, 110-150 cm): This instrument is designed for precise embolic agent delivery within the cavernous sinus.[33]

Embolization Devices and Materials

After successful SOV cannulation, embolization of the CCF is performed using appropriate embolic materials.

- Coils (detachable or pushable, 3-6 mm): This is used for gradual occlusion of the fistula and diversion of blood flow.

- Liquid embolic agents (N-butyl cyanoacrylate [nBCA], Onyx, and Squid): Polymerizing agents for permanent occlusion of high-flow fistulas.

- Particulate embolics (polyvinyl alcohol [PVA], Gelfoam®, and microspheres)- Occasionally used for temporary flow reduction in select cases.

- Balloon catheters (dual-lumen, optional): These may be used alongside coils or liquid embolic agents to allow controlled deployment.[34]

Hemostasis and Complication Management

Due to the delicate anatomy of the orbit and cavernous sinus, appropriate measures must be in place to manage potential bleeding or venous injury.

- Hemostatic agents (fibrin sealant, Surgicel®, and Gelfoam®): These help in controlling minor bleeding at venous access sites.

- Orbital compression devices: They reduce the risk of postprocedural venous congestion or retrobulbar hemorrhage.

- Reversal agents (protamine and tranexamic acid): These agents are used for managing unexpected bleeding complications.

- Emergency surgical instruments (orbital decompression set and microsurgical tools): They are available for rapid intervention in cases of orbital hematoma or vessel rupture.[35]

Anesthesia and Patient Monitoring Equipment

Ensuring procedural safety during SOV cannulation requires meticulous sedation management and continuous hemodynamic monitoring.

- Sedation setup (dexmedetomidine, propofol, or midazolam infusion): This provides adequate patient comfort while allowing cooperation.

- Intraoperative neuromonitoring: This assesses ocular motility and optic nerve function throughout the procedure.

- Noninvasive blood pressure and oxygen monitoring: This helps maintain stable hemodynamics during embolization.

SOV cannulation for CCF treatment is a highly specialized procedure that demands advanced imaging, precise vascular instruments, and appropriate embolization materials. Real-time fluoroscopy and ultrasound guidance, microcatheters, embolic agents, and meticulous hemostasis management are essential to ensure a safe and effective intervention.[36]

Personnel

This procedure requires a team with expertise in neurointervention and orbital surgery, and it can be performed in the angiography suite with support from anesthesia staff. SOV cannulation for CCF is a highly specialized procedure that demands a multidisciplinary approach to ensure precision, safety, and successful treatment. Each healthcare team member is vital in patient assessment, procedural execution, and postprocedure care.

Interventional Neuroradiologist

Interventional neuroradiologists serve as the primary operators and perform SOV cannulation and embolization. Their responsibilities include:

- Using fluoroscopic guidance and DSA for real-time visualization of venous access and embolic agent placement.

- Determining the best approach based on anatomical variations, flow dynamics, and fistula complexity.[11]

Neuro-Ophthalmologist or Oculoplastic Surgeon

Neuro-ophthalmologists or oculoplastic surgeons are crucial healthcare providers in SOV cannulation. Their responsibilities include:

- Providing expertise in orbital anatomy and assisting with precise localization of the SOV.

- Helping with orbital exposure and offering microsurgical assistance in cases requiring a surgical approach to the SOV.

- Evaluating ocular complications, orbital congestion, and venous stasis before and after the procedure.[37]

Interventional Neurologist or Neurosurgeon

Interventional neurologists or neurosurgeons contribute to the comprehensive management of CCF. Their responsibilities include:

- Assisting in procedural planning and decision-making for treating high- and low-flow CCFs.

- Providing backup for alternative access routes, including transvenous or transarterial approaches.

- Managing postprocedural neurological complications, such as cranial nerve dysfunction.[38]

Anesthesiologist or Sedation Specialist

Anesthesiologists or sedation specialists play a vital role in maintaining patient safety and comfort throughout the SOV cannulation procedure. Their responsibilities include:

- Ensuring hemodynamic stability during the procedure.

- Administering conscious sedation or general anesthesia, depending on the complexity of the procedure.

- Monitoring vital signs, airway management, and intraoperative sedation levels.[39]

Interventional Radiology Nurse

Interventional radiology nurses play a critical role in ensuring procedural efficiency and patient safety during SOV cannulation. Their responsibilities include:

- Assisting with patient preparation, sterile field setup, and medication administration.

- Monitoring vital signs in patients and ensuring readiness for emergency interventions.

- Providing postprocedural care instructions and supporting recovery monitoring.[40]

Scrub Technician or Operating Room Assistant

Scrub technicians or operating room assistants are essential for maintaining procedural efficiency and sterility during SOV cannulation. Their responsibilities include:

- Preparing and arranging microcatheters, guidewires, embolic agents, and vascular access kits.

- Maintaining sterility of the procedure and assisting the primary operator by providing necessary instruments.

- Ensuring smooth workflow and instrument availability during cannulation.[41]

Medical Physicist or Imaging Specialist

Medical physicists or imaging specialists play a vital role in ensuring high-quality imaging and radiation safety during SOV cannulation. Their responsibilities include:

- Optimizing fluoroscopy and DSA settings to enhance visualization while minimizing radiation exposure.

- Assisting in 3D imaging and road-mapping guidance for accurate catheter navigation.

- Troubleshooting imaging equipment to prevent technical issues that could disrupt the procedure.[42]

Emergency Response Team

The emergency response team, comprising critical care specialists, vascular surgeons, and backup interventionalists, is prepared to manage potential complications such as orbital hemorrhage, venous rupture, retrobulbar hematoma, and thromboembolism.

Successful SOV cannulation for CCF requires a coordinated, highly skilled healthcare team with expertise in interventional neuroradiology, neuro-ophthalmology, anesthesia, radiology, and emergency management. This collaborative effort ensures precision, safety, and the best possible patient outcomes in this complex and potentially life-altering procedure.[27]

Preparation

DSA is the gold standard for diagnosing and initiating therapy for CCF. However, CT, CT angiography, and MRI may be used to confirm the diagnosis if there is any uncertainty and to rule out other potential causes (such as tumors, posterior communicating artery aneurysms, or infections). A comprehensive patient history and physical examination should be conducted on the day of the procedure to assess the need for intervention.[43] The preparation phase involves patient evaluation, imaging assessment, procedural planning, equipment setup, and team coordination.[44]

Patient Evaluation and Selection

- A detailed history and clinical examination are essential to assessing the severity of orbital congestion, visual impairment, and neurological deficits.

- The evaluation of symptoms such as proptosis, chemosis, orbital bruit, and elevated IOP helps determine the urgency of the intervention.

- Systemic conditions such as coagulopathy, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular health should be reviewed to minimize procedural risks.[19]

Imaging and Preprocedural Assessment

- DSA is the gold standard for confirming the type and flow characteristics of CCF.

- MRI and MR angiography provide detailed insights into soft tissue involvement, venous drainage patterns, and secondary complications.

- CT angiography is useful for mapping venous anatomy and identifying variations in the SOV course.

- Ultrasound, including B-scan and Doppler imaging, helps assess venous distension, thrombus formation, and optimal venous access points.[22]

Anesthesia and Sedation Plan

- The procedure can be performed under local anesthesia with conscious sedation or general anesthesia, depending on the patient's tolerance and anatomical complexity.

- Intravenous sedation (eg, midazolam, fentanyl, or propofol) ensures patient comfort while maintaining cooperation.

- Local anesthetic (lidocaine with epinephrine) is used for periorbital numbing to minimize discomfort during the procedure.[39]

Anticoagulation and Hemostasis Considerations

- The patient's anticoagulation status must be carefully evaluated, with adjustments made if the patient is taking warfarin, DOACs, or aspirin.

- Intraprocedural heparinization may be needed to prevent thrombosis during catheterization.

- Preprocedural blood tests (such as complete blood count [CBC], prothrombin time/international normalized ratio [PT/INR], and activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT]) help assess coagulation status and ensure readiness for the intervention.[45]

Equipment and Surgical Setup

Sterile field preparation involves thorough disinfection of the periorbital region and proper draping to maintain asepsis. The following microsurgical instruments and vascular access kits should be arranged:

- Microsurgical scalpels for venous exposure (if a direct surgical approach is needed).

- Microcatheters and guidewires for venous navigation.

- Fluoroscopy-compatible contrast agents to visualize vessel entry and flow dynamics.

- Embolic agents (eg, coils, Onyx, and nBCA glue) that are prepared for fistula occlusion.[46]

Team Coordination and Role Assignment

- An interventional radiologist or neurosurgeon leads the cannulation and embolization process.

- A neuro-ophthalmologist or oculoplastic surgeon assists in localizing the SOV and handling orbital structures.

- An anesthesiologist manages patient sedation, airway monitoring, and hemodynamic stability.

- Scrub nurses and radiology technicians are responsible for properly setting up and handling instruments throughout the procedure.[47]

Emergency Preparedness

- Complication protocols must be established for potential issues such as:

- Venous rupture leading to orbital hematoma.

- Retinal ischemia due to embolization reflux.

- Acute increases in IOP due to venous congestion.

- Resuscitation equipment, reversal agents (eg, protamine for heparin), and surgical backup must be readily available.

Thorough preparation is essential for successful SOV cannulation for CCF. Proper patient selection, imaging assessment, anesthesia planning, equipment setup, and multidisciplinary coordination minimize risks and ensure optimal outcomes.[48]

Technique or Treatment

SOV cannulation is a critical technique for treating CCF, particularly when conventional transarterial or transfemoral approaches are unsuccessful. This minimally invasive yet technically demanding procedure provides direct access to the cavernous sinus through the orbit, enabling precise embolization and fistula occlusion.

Informed consent must be obtained, with a thorough explanation of the procedure's risks and benefits. The angiography suite should be fully equipped and staffed with the necessary personnel. A femoral sheath is placed using a standard angiographic technique. The sterile field encompasses the eye, eyebrow, forehead, and cheek to maintain asepsis.[27]

Preoperative Preparation

A meticulous preoperative assessment is essential to ensure procedural success and patient safety before initiating SOV cannulation.

- Patient selection and indications: SOV cannulation is primarily indicated in cases of high-flow direct CCFs or low-flow indirect CCFs where standard transfemoral venous approaches are inaccessible.

- Imaging guidance: Advanced imaging techniques, such as DSA, CT angiography, and MR angiography, are used to confirm the anatomy of the SOV, the location of the fistula, and the vascular architecture.

- Anesthesia and patient positioning: The procedure is performed under general anesthesia to ensure complete immobilization. The patient is positioned supine with a slightly extended head to optimize access to superior orbital structures.[49]

Incision

A small incision is made in the medial upper eyelid crease, or, alternatively, a sub-brow incision may be used. The incision is then extended through the orbicularis oculi muscle using blunt dissection with Stevens scissors. Achieving hemostasis at this stage is crucial, as oozing from the tissues beneath the orbicularis oculi muscle can interfere with the surgical site.[14]

Surgical Exposure of the Superior Ophthalmic Vein

Given the deep location of the SOV within the orbit, various approaches can be used to achieve adequate exposure.

- Transcutaneous upper eyelid approach: A small sub-brow or medial upper eyelid crease incision provides access to the SOV along the superior orbital rim.

- Transconjunctival approach: A transconjunctival incision through the fornix can provide direct visualization of the SOV while minimizing tissue disruption.

- Ultrasound or fluoroscopy guidance: When the SOV is difficult to locate, Doppler ultrasound or intraoperative fluoroscopy can aid in precise localization and puncture.[50]

Orbitotomy

The orbital septum is opened medially, exposing the medial retroseptal fat pad, which appears whiter than the central fat pad. This fat is bluntly dissected in a posterolateral direction until an arterialized feeder of the SOV is identified, which is then traced back to locate the main trunk of the SOV. Milking the vessels can help determine the flow direction if multiple feeders are present. In cases where the vessel is not significantly engorged, some suggest performing an osteotomy to improve exposure to the deep orbit. However, this approach has not been necessary in over 40 cases.

Sewell retractors and moist neurosurgical cottonoids are invaluable during this stage. When the surgeon is familiar with the anatomy of the angular vessels, including the supraorbital and supratrochlear vessels, the SOV can be identified relatively easily by following one of these vessels into the SOV. Another helpful technique involves using a blunt separating motion with a hemostat or Stevens scissors. This dissection allows for the separation of the superomedial orbital tissues, thereby exposing the dilated SOV.

For completeness, it should be noted that some surgeons perform an additional brow incision, dissecting the subcutaneous tissues and the frontalis muscle until the orbital rim is reached. They then create a small orbitofrontal bone flap at the orbital rim. In this approach, the SOV can be identified within the superomedial portion of the periorbital cone after gentle retraction of the superior rectus.[2] However, osteotomies are generally unnecessary when proper retraction, lighting, and anatomical knowledge are available.

Isolation of the Superior Ophthalmic Vein

The SOV is bluntly dissected, freed from surrounding attachments, and exposed to the surface for incision of the vessel wall. Rubber loops or 4-0 silk sutures may be used around the SOV to facilitate manipulation and maintain tension. Rubber loops may be placed around the SOV to facilitate manipulation, keeping the vein taut (4-0 silk sutures can also be used). The vein is then accessed with an angiocatheter, and brisk bleeding confirms a full-thickness opening, enabling cannulation. The angiocatheter is typically secured with a suture, and the catheter is advanced toward the cavernous sinus under fluoroscopic guidance, with a gentle injection of contrast to confirm proper placement.

Once the placement is confirmed, cavernous sinus obliteration is performed using standard endovascular techniques, such as liquid embolic agents or coiling.[11] Care is taken to preserve at least one ophthalmic vein to prevent a sudden increase in IOP. Arterial angiography is then conducted to verify fistula obliteration before catheter withdrawal. The SOV is ligated distal to the insertion site unless it is large and thick-walled, in which case it is primarily closed. The orbit may be irrigated with an antibiotic solution to minimize the risk of infection.

Cannulation of the Superior Ophthalmic Vein

- Venous identification and dissection: Once the SOV is visualized, meticulous dissection is performed to isolate the vein without damaging surrounding structures.

- Direct venous puncture: A micropuncture needle (21G or finer) is used to puncture the vein under direct visualization. A small-caliber sheath (4-5 F) is then advanced into the vein to maintain vascular access.

- Guidewire navigation: A hydrophilic guidewire (0.014 in) is carefully navigated through the SOV, following its tortuous course into the cavernous sinus. Care must be taken to avoid venous perforation or endothelial trauma.[51]

Embolization of the Carotid-Cavernous Fistula

- Microcatheter advancement: A coaxial microcatheter system is introduced over the guidewire and advanced into the fistulous communication between the internal carotid artery and the cavernous sinus.

- Embolic agent selection:

- Coils: Detachable platinum coils are often used to occlude high-flow fistulas.

- Liquid embolics (Onyx and nBCA glue): These agents provide permanent closure of the fistulous tract.

- Balloon-assisted embolization: A balloon catheter may be inflated within the fistula to facilitate controlled embolization in some cases.

- Real-time angiographic confirmation: Continuous fluoroscopic monitoring is essential to ensure complete occlusion of the CCF while preserving normal venous outflow.[4]

Postprocedure Closure and Recovery

After meticulous hemostasis is obtained, the orbital incision is closed using simple 6-0 catgut sutures. If fistula recurrence is suspected, follow-up angiography is recommended. Clinical follow-up is recommended at 3 and 6 months post-intervention. The patient's vision and IOPs are assessed.

- Sheath and catheter removal: After successful embolization, the microcatheter and sheath are carefully withdrawn while hemostasis is ensured at the venous access site.

- Wound closure: Depending on the surgical approach, the skin or conjunctival incision is closed using fine, absorbable sutures.

- Postoperative monitoring: The patient is monitored for potential complications, including orbital hematoma, venous thrombosis, and cranial nerve dysfunction.[52]

Follow-Up and Long-Term Outcome

- Angiographic follow-up: DSA or MR angiography is repeated at 1 and 6 months postprocedure to confirm fistula closure and absence of recurrence after the procedure.

- Ophthalmological assessment: Regular ophthalmological evaluations are essential to assess for persistent proptosis, diplopia, or optic neuropathy.

- Functional recovery: Most patients experience progressive improvement in visual function and orbital congestion following successful SOV cannulation and embolization.

SOV cannulation is a technically challenging yet highly effective method for treating CCF when standard endovascular routes are not viable. This method requires meticulous surgical exposure, precise catheter navigation, and targeted embolization techniques to achieve optimal outcomes while minimizing procedural risks. This approach underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary team, incorporating ophthalmology, neuroradiology, and neurosurgery to successfully manage complex neurovascular disorders.[53]

Complications

The surgical cutdown of the SOV is generally well-tolerated. However, complications can include damage to orbital structures, particularly the superficial nerves and extraocular muscles, though such occurrences are rarely reported in the literature. During endovascular treatment, vessel rupture and subsequent hemorrhage are possible. In an observed case of SOV rupture, no retro-orbital hematoma was noted, and the patient was successfully managed conservatively. Aggressive embolization of the cavernous sinus may also lead to cranial nerve deficits.[54]

SOV cannulation is a valuable technique for the endovascular treatment of CCFs, particularly when conventional transvenous access routes, such as the IPS, are unavailable. Despite its effectiveness, this procedure carries significant risks and potential complications that necessitate careful consideration and expert management to ensure patient safety and achieve optimal clinical outcomes.[55]

Vascular Injury and Venous Perforation

Vascular injury and venous perforation are potential risks during SOV cannulation due to the vein's thin-walled nature. Inadvertent perforation can result in orbital hemorrhage, venous rupture, and hematoma formation, leading to proptosis, pain, and optic nerve compression. In severe cases, uncontrolled bleeding may require urgent orbital decompression or surgical intervention.[56]

Orbital Hematoma and Compartment Syndrome

SOV cannulation involves manipulating a delicate vascular structure within the confined space of the orbit. Accidental venous rupture may lead to a rapid increase in IOP, resulting in orbital compartment syndrome. This condition can cause:

- Acute vision loss due to optic nerve compression.

- Restricted extraocular motility, causing diplopia and strabismus.

- Severe periorbital swelling and proptosis, leading to corneal exposure and secondary ocular complications.

- Pain and venous congestion exacerbate preexisting CCF-related symptoms.[57]

Retrobulbar Hemorrhage

Intraoperative trauma or postprocedure venous leakage can lead to retrobulbar hemorrhage—a critical condition that may compromise the optic nerve function and ocular perfusion. If left untreated, this condition can progress to ischemic optic neuropathy, potentially leading to permanent vision loss. Immediate management involves orbital decompression, systemic steroids, and IOP-lowering medications.[58]

Cranial Nerve Palsy and Neurological Deficits

The cavernous sinus contains multiple cranial nerves (CN III, IV, V1, V2, and VI) responsible for controlling ocular movements and facial sensation. During embolization, excessive compression or embolic material reflux into these nerves can cause the following conditions:

- Oculomotor nerve palsy (CN III): This results in ptosis, impaired eye movements, and dilated pupils.

- Trochlear nerve palsy (CN IV): This leads to vertical diplopia.

- Abducens nerve palsy (CN VI): This causes horizontal diplopia and esotropia.

- Trigeminal nerve dysfunction (CN V1 and V2 branches): This results in hypoesthesia, dysesthesia, or pain in the ophthalmic and maxillary regions. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Cranial Nerve III Palsy," for more information.

Venous Thrombosis and Recanalization Failure

Incomplete embolization or iatrogenic injury to the SOV can lead to venous thrombosis, resulting in persistent ocular congestion and delayed symptom resolution. Additionally, partial recanalization of the fistula may cause symptom recurrence, requiring repeat embolization or alternative surgical interventions.[59]

Embolic Material Migration

The risk of unintended migration of embolic agents (eg, coils, liquid embolic, or glue) into adjacent venous structures or arterial systems can lead to severe complications, including:

- Ophthalmic artery occlusion, resulting in sudden vision loss.

- Cerebral embolism, causing stroke or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs).

- Contralateral venous congestion, exacerbating intracranial hypertension and leading to secondary neurological sequelae.[60]

Infection and Orbital Cellulitis

As with any invasive procedure, maintaining a sterile technique is essential to prevent postoperative infection and orbital cellulitis. Improper handling of catheters and guidewires can introduce pathogens, leading to local abscess formation, endophthalmitis, or even cavernous sinus thrombosis. This life-threatening condition requires aggressive antibiotic therapy and, in some cases, surgical drainage. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Orbital Cellulitis," for more information.

Ocular Hypertension and Secondary Glaucoma

Obstruction of normal venous outflow after embolization may lead to a persistent rise in IOP, which increases the risk of the following conditions:

- Secondary angle-closure glaucoma, requiring IOP-lowering medications or surgical interventions.

- Optic nerve damage, contributing to progressive visual field loss.

- Corneal edema, affecting vision quality and ocular comfort. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma," for more information.

Anesthetic Complications

SOV cannulation is typically performed under general anesthesia or deep sedation to minimize patient discomfort and ensure precise surgical control. However, anesthesia-related complications, such as hypotension, respiratory depression, or allergic reactions, can present additional risks, particularly in older or medically fragile patients.[61]

Technical Challenges and Procedural Failure

Not all patients are suitable candidates for SOV cannulation due to anatomical variations, small vein caliber, or prior venous thrombosis. In some cases, failure to successfully access the SOV may require conversion to an alternative approach, such as direct puncture of the cavernous sinus or transarterial embolization, which may involve higher procedural risks.[27]

Strategies to Minimize Complications

- Preoperative imaging and planning: High-resolution MRI, CT angiography, and DSA should be utilized to assess vascular anatomy, SOV patency, and alternative access routes before attempting cannulation.

- Ultrasound-guided cannulation: Real-time ultrasound guidance enhances procedural accuracy and helps reduce the risk of perforation and hematoma formation.

- Meticulous embolization technique: Proper selection of embolic materials and controlled injections are essential to prevent embolic migration and unintended vascular occlusion.

- Postoperative monitoring: Regular follow-up, including fundoscopy, IOP measurement, and repeat angiography, is crucial for detecting early signs of complications and recurrence.

- Multidisciplinary approach: Collaboration among healthcare providers, including neurointerventional radiologists, ophthalmologists, and neurosurgeons, ensures comprehensive patient care and timely intervention if complications arise.[62]

Although SOV cannulation is crucial for managing CCFs, it carries inherent risks. Recognizing potential complications and implementing preventive strategies can significantly enhance procedural safety, patient outcomes, and long-term success. Proper patient selection, technical expertise, and postprocedure surveillance are critical in minimizing adverse events and optimizing therapeutic benefits in CCF management.[63]

Clinical Significance

Over 95% of patients who underwent endovascular embolization via direct surgical access to the SOV remained symptom- and recurrence-free at the last clinical follow-up in the reported case series.[1][2][11][16][64] Even in cases of incomplete embolization, clinical improvement has been observed. Direct cannulation of the SOV is a safe and effective approach for the endovascular treatment of indirect CCFs, particularly when other endovascular options have been exhausted.[65][66][67][68]

Role of SOV Cannulation in the Treatment of CCF

The primary goal in treating CCFs is to eliminate abnormal arterial blood shunting into the venous system while preserving the integrity of the carotid artery and cranial circulation. SOV cannulation is a direct transorbital approach that provides precise access to the cavernous sinus for embolization procedures when other routes, such as transfemoral arterial or transvenous approaches, are not feasible. This technique offers a highly effective pathway for targeted embolization using coils, liquid embolic agents, or balloons, ensuring successful fistula closure while minimizing complications.[5]

Advantages Over Other Access Routes

- Alternative for failed transvenous approaches: SOV cannulation offers a viable alternative for direct cavernous sinus embolization in cases where the IPS is thrombosed or inaccessible due to anatomical variations.

- Minimally invasive: Unlike open surgical methods that may require craniotomy or direct exposure to the cavernous sinus, SOV cannulation is less invasive, resulting in reduced surgical trauma and enhanced recovery outcomes.

- Immediate symptom relief: Patients undergoing successful SOV-guided embolization experience rapid alleviation of symptoms such as proptosis, chemosis, and pulsatile tinnitus, which is common in high-flow CCFs.

- Vision preservation: By reducing intraocular venous congestion and ocular hypertension, SOV cannulation helps prevent secondary complications, including ischemic optic neuropathy, glaucoma, and retinal ischemia, which can lead to permanent vision loss.[5]

Impact on Visual and Neurological Outcomes

CCFs often present with progressive visual impairment, ocular motility disturbances, and severe orbital congestion, all of which can worsen without timely intervention. Research has demonstrated that early embolization through SOV cannulation results in substantial functional recovery by alleviating venous hypertension and restoring normal hemodynamics within the cavernous sinus. Additionally, cranial nerve dysfunction caused by compression from engorged venous structures in the cavernous sinus often improves significantly following embolization, helping prevent permanent neurological deficits.[6]

Multidisciplinary Importance in Neurovascular Disease Management

The success of SOV cannulation in managing CCFs highlights the collaborative role of interventional neuroradiologists, neurosurgeons, and ophthalmologists. This multidisciplinary approach ensures:

- Accurate preoperative planning: High-resolution CT angiography, MRI, and DSA are used to evaluate fistula characteristics and determine the most appropriate treatment strategy.

- Precision-guided intervention: Real-time fluoroscopic guidance ensures safe cannulation of the delicate ophthalmic venous system, reducing procedural risks such as venous rupture or hemorrhage.

- Postoperative monitoring: Regular follow-up with Doppler ultrasound, repeat angiography, and ophthalmological assessments ensure successful fistula closure and early detection of residual shunting or recurrence.[7]

Potential Risks and Considerations

Although SOV cannulation is an effective technique, it carries potential risks, such as venous perforation, orbital hematoma, and transient ocular motor dysfunction. These risks require meticulous technique, real-time imaging, and careful patient selection. In cases where SOV access is challenging due to thrombosis or anatomical variations, alternative approaches, such as direct superior orbital fissure access or contralateral transvenous embolization, may be considered.[49]

SOV cannulation has transformed the management of CCFs, especially in cases where traditional endovascular routes fail. Direct access to the cavernous sinus enables successful embolization, rapid symptom relief, and the prevention of vision-threatening complications. The technique’s minimally invasive nature, high success rates, and ability to preserve neuro-ophthalmic function highlight its clinical importance in modern neurovascular interventions. Future advancements in imaging, catheter technology, and embolic materials will further refine this technique, enhancing its safety and efficacy for patients with complex CCFs and orbital venous pathologies.[14]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

SOV cannulation for treating CCF requires a collaborative, interprofessional approach. A neurointerventionalist is essential for femoral access and the subsequent endovascular treatment of the fistula once the vein has been cannulated. An orbital surgeon performs the surgical procedure, while trained staff assist in the interventional suite. Anesthetists are crucial for monitoring the patient throughout the process. Nursing and clinical staff play a key role in screening patients on the day of surgery to confirm ongoing symptoms. Pharmacists may assist with postoperative pain management, which is typically minimal in this setting. An interprofessional healthcare team approach is essential for optimizing patient care and ensuring better outcomes.[27]

This high-risk, multidisciplinary procedure demands seamless coordination among allied healthcare professionals, including physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, radiologists, and anesthesiologists. Improving teamwork, communication, and care strategies throughout this complex intervention is crucial for enhancing patient-centered outcomes, ensuring procedural success, and promoting patient safety.[4]

Skills and Strategy

- Ophthalmologists and neurosurgeons need advanced microsurgical skills to achieve precise venous access while minimizing IOP elevation and preventing neurovascular injury.

- Radiologists are crucial in preprocedural imaging, real-time fluoroscopic guidance, and postprocedural monitoring, which confirms successful embolization and prevents recurrence.

- Anesthesiologists are responsible for maintaining optimal sedation, hemodynamic stability, and pain control, ensuring procedural safety while preventing complications related to patient movement.[69]

Interprofessional Communication and Ethics

- Clear, structured communication among healthcare team members, utilizing standardized protocols (such as checklist-based approaches), ensures efficient decision-making and minimizes errors during high-risk procedures, such as guidewire navigation and embolic material deployment.

- Ethical considerations involve informed consent discussions, ensuring that patients understand procedural risks, available alternative treatment options, and postoperative expectations.[70]

Care Coordination and Patient-Centered Outcomes

- Nurses are responsible for coordinating preprocedural preparation, medication reconciliation, and patient education to ensure optimal procedural readiness.

- Postoperatively, an interprofessional healthcare team monitors for complications such as orbital compartment syndrome, venous congestion, or new-onset cranial nerve dysfunction, ensuring early detection and prompt intervention.

- Pharmacists are crucial in optimizing anticoagulation management and reducing the risk of thrombotic or hemorrhagic complications, particularly in patients with underlying vascular comorbidities.[71]

By fostering strong interprofessional collaboration, continuous training, and standardized workflow protocols, the healthcare team improves patient safety, procedural success, and long-term visual and neurological outcomes for individuals undergoing SOV cannulation for CCF.[72]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

SOV cannulation for the treatment of CCF is a multidisciplinary procedure requiring seamless coordination among nurses, allied health professionals, anesthesiologists, interventional radiologists, ophthalmologists, and neurosurgeons. Effective interprofessional collaboration enhances procedural safety, optimizes patient outcomes, and facilitates efficient postoperative recovery.

Preprocedural Interventions

- Patient preparation: Effective preprocedural interventions are critical for ensuring patient readiness, optimizing procedural outcomes, and minimizing complications during SOV cannulation for CCF treatment.

- Nurses provide preprocedural education, obtain informed consent, and offer psychological reassurance to patients.

- Allied healthcare professionals, including imaging specialists, conduct preprocedural imaging studies such as CT angiography, MR angiography, and DSA to guide intervention planning.

- The anesthesia team evaluates the patient’s American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, airway management needs, and sedation plan to ensure procedural safety and optimal comfort.

- Laboratory technicians assist in coagulation screening, renal function testing, and medication reconciliation before the intervention.[73]

Intraprocedural Interventions

- Monitoring and procedural assistance: Effective intraprocedural interventions are essential for maintaining patient stability, ensuring technical precision, and optimizing the success of SOV cannulation during CCF treatment.

- Anesthesiologists oversee sedation, airway management, and hemodynamic monitoring to prevent fluctuations that could complicate venous access.

- Nurses and radiology technologists assist with patient positioning, sterile field maintenance, and microcatheter system handling under fluoroscopic guidance.

- Radiology personnel provide real-time imaging support to ensure accurate venous entry, precise guidewire manipulation, and controlled embolic agent deployment.[74]

- Safety and complication management: Proactive safety measures and complication management during SOV cannulation are essential to minimize risks and ensure optimal patient outcomes.

- Continuous monitoring of IOP, orbital swelling, and real-time neurological function monitoring are critical for the early detection of orbital compartment syndrome.

- Preprocedural antihistamines or corticosteroids may be administered to prevent allergic reactions to contrast agents, with emergency medications readily available for immediate intervention.[75]

Postprocedural Interventions

- Recovery and complication prevention: Postprocedural care focuses on recovery optimization and complication prevention through vigilant monitoring, effective pain management, and patient education.

- Ongoing neurological monitoring is essential to detect signs of cranial nerve dysfunction, venous congestion, or new-onset ophthalmoplegia.

- Pain management balances adequate analgesia with anticoagulation considerations to reduce the risk of thrombotic complications.

- Nurses provide patient education on postprocedure activity restrictions, warning signs of complications, and the necessity of follow-up imaging.[76]

- Discharge planning and follow-up coordination: Effective discharge planning and follow-up coordination are essential to ensure continued recovery, monitor for recurrence, and optimize long-term outcomes.

- Allied health professionals facilitate scheduling for postprocedural neuro-ophthalmic evaluations, radiographic follow-up, and rehabilitation therapy when needed.

- Nursing staff reinforce medication adherence and coordinate multidisciplinary follow-ups to assess CCF resolution and prevent recurrence.

The successful execution of SOV cannulation for CCF requires a highly coordinated, interprofessional team approach. The combined expertise of nurses, anesthesiologists, radiologists, ophthalmologists, and allied healthcare professionals is essential for optimizing procedural safety, managing intraoperative challenges, and ensuring comprehensive postprocedural care. The interprofessional healthcare team enhances clinical outcomes and supports a smooth recovery for patients undergoing this specialized procedure through vigilant monitoring, early complication detection, and patient-centered interventions.[77]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

SOV cannulation for treating CCF is a complex, high-risk procedure that necessitates a coordinated approach by an interprofessional team. Collaboration among healthcare professionals, including nurses, allied health professionals, anesthesiologists, radiology technologists, and ophthalmologists, is vital to ensure optimal patient outcomes. Continuous monitoring throughout the preprocedural, intraprocedural, and postprocedural phases focuses on patient safety, procedural effectiveness, and early detection of complications.[7]

Preprocedural Responsibilities

Nurses and allied healthcare professionals play a critical role in preparing the patient, obtaining informed consent, and ensuring compliance with preoperative imaging and laboratory evaluations. Preprocedural assessments include:

- Baseline neurological and ophthalmic examination to assess visual acuity, IOP, ocular motility, and proptosis.

- Preoperative bloodwork (CBC, coagulation profile, and renal function tests) to evaluate patient readiness.

- Medication review and administration of preprocedural medications, such as prophylactic antibiotics, anticoagulation management, and sedation.

- Psychological preparation and patient education regarding procedural steps, expected outcomes, and potential risks.[78]

Intraprocedural Monitoring

The interprofessional healthcare team collaborates during the procedure to ensure comprehensive monitoring and patient safety.

- Sedation and anesthesia support: Effective sedation and anesthesia management are crucial during the procedure, with continuous monitoring to ensure patient stability and safety.

- Anesthesiologists or sedation nurses monitor oxygenation, ventilation, hemodynamics, and level of sedation.

- Rapid intervention involves immediate action in response to airway compromise, hemodynamic instability, or adverse drug reactions.[74]

- Hemodynamic and neurological monitoring: Hemodynamic and neurological monitoring during the procedure is crucial to ensure early detection of complications and maintain patient safety.

- Continuous monitoring of vital signs, including blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation, is essential for detecting changes related to venous congestion, systemic embolization, or other procedural complications.

- Vigilance for sudden increases in IOP, worsening proptosis, or signs of orbital compartment syndrome is critical.

- Detection of neurological deficits is also crucial to identify cavernous sinus thrombosis or embolization-related ischemia. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Vital Sign Assessment," for more information.

- Imaging and procedural assistance: Imaging and procedural assistance are essential for successful SOV cannulation, with radiology technologists and scrub nurses supporting the procedure.

- Radiology technologists ensure proper fluoroscopic guidance and imaging documentation for precise venous cannulation.

- Scrub nurses support the procedure by handling the microcatheter, preparing embolic agents, and maintaining a sterile field. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Fluoroscopic Angiography Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation," for more information.

Postprocedural Care and Recovery Monitoring

Following the procedure, nurses and allied healthcare professionals are crucial in ensuring a safe recovery, detecting early complications, and providing patient education. Key responsibilities are listed below.

- Immediate postoperative monitoring: Postoperative monitoring is essential to detect early complications and ensure a smooth recovery.

- Frequent neurological checks are necessary to assess for changes in visual function, extraocular motility, and signs of orbital hemorrhage.

- Pain can be managed by using appropriate analgesics while avoiding medications that increase bleeding risk.

- Assessment of vascular access sites is required for signs of hematoma, infection, or excessive swelling.[79]

- Complication surveillance: Effective surveillance is crucial for the postprocedural care and recovery of patients.

- Early detection is necessary for managing potential issues such as venous thrombosis, IOP spikes, and the emergence of new neurological deficits.

- Prompt identification of contrast-induced nephropathy or allergic reactions related to imaging contrast agents is essential to prevent further complications.

- Discharge planning and patient education: Effective discharge planning involves educating patients, coordinating follow-up care, and providing clear guidance to patients to ensure successful outcomes.

- Patients should be educated on postprocedural warning signs, including vision loss, severe headache, eye redness, or proptosis.

- Follow-up ophthalmology and neurology appointments should be coordinated for long-term monitoring of fistula resolution.

- Patient concerns regarding activity restrictions, medication adherence, and follow-up imaging studies should be addressed.

The success of SOV cannulation for CCF treatment depends mainly on effective collaboration within the interprofessional healthcare team. Nurses, allied healthcare professionals, and physicians are crucial in patient preparation, ensuring procedural safety, and managing postprocedural recovery. Their combined expertise in monitoring, patient education, and complication prevention significantly enhances outcomes and reduces risks associated with this complex procedure.[80]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Superior Ophthalmic Vein, Inferior Ophthalmic Vein, and Cavernous Sinus.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Teng MM, Guo WY, Huang CI, Wu CC, Chang T. Occlusion of arteriovenous malformations of the cavernous sinus via the superior ophthalmic vein. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 1988 May-Jun:9(3):539-46 [PubMed PMID: 3132828]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWolfe SQ, Cumberbatch NM, Aziz-Sultan MA, Tummala R, Morcos JJ. Operative approach via the superior ophthalmic vein for the endovascular treatment of carotid cavernous fistulas that fail traditional endovascular access. Neurosurgery. 2010 Jun:66(6 Suppl Operative):293-9; discussion 299. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000369705.91485.38. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20489519]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLucas Cde P, Mounayer C, Spelle L, Piotin M, Rezende MT, Moret J. Endoarterial management of dural arteriovenous malformations with isolated sinus using Onyx-18: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2007 Nov:61(5 Suppl 2):E293-4; discussion E294. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000303981.34622.39. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18091221]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHan M, Chen T, Ediriwickrema L. Intra-operative visualization of the superior ophthalmic vein in carotid-cavernous fistula. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2025 Feb 12:():1. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2025.2460168. Epub 2025 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 39937534]

Liang B, Moskalik AD, Taylor MN, Waldau B. Transvenous embolization of a carotid-cavernous fistula via the inferior ophthalmic vein: illustrative case. Journal of neurosurgery. Case lessons. 2024 Aug 12:8(7):. pii: CASE24183. doi: 10.3171/CASE24183. Epub 2024 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 39133941]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrunasso L, Casamassima N, Abrignani S, Sturiale CL, Incandela F, Giammalva GR, Iacopino DG, Maugeri R, Craparo G. Flow diversion for indirect carotid-cavernous fistula: Still an off-label indication? Surgical neurology international. 2023:14():65. doi: 10.25259/SNI_1113_2022. Epub 2023 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 36895234]

Catapano JS, Srinivasan VM, De La Peña NM, Singh R, Cole TS, Wilkinson DA, Baranoski JF, Rutledge C, Pacult MA, Winkler EA, Jadhav AP, Ducruet AF, Albuquerque FC. Direct puncture of the superior ophthalmic vein for carotid cavernous fistulas: a 21-year experience. Journal of neurointerventional surgery. 2023 Oct:15(10):948-952. doi: 10.1136/jnis-2022-019135. Epub 2022 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 36261279]

Steeg K, Krombach GA, Friebe MH. A Review of Needle Navigation Technologies in Minimally Invasive Cardiovascular Surgeries-Toward a More Effective and Easy-to-Apply Process. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2025 Jan 16:15(2):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics15020197. Epub 2025 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 39857081]

Vladimir B, Ivan V, Zarko N, Aleksandra N, Mihailo M, Nemanja J, Marina M, Aleksandar S, Vuk S, Danica G. Transorbital hybrid approach for endovascular occlusion of indirect carotid-cavernous fistulas-Case report and systematic literature review. Radiology case reports. 2022 Sep:17(9):3312-3317. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2022.06.043. Epub 2022 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 35846510]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTrennheuser S, Reith W, Kühn JP, Morris LGT, Bozzato A, Naumann A, Schick B, Yilmaz U, Linxweiler M. Transorbital embolization of cavernous sinus dural arterio-venous malformations with surgical exposure and catheterization of the superior ophthalmic vein. Interventional neuroradiology : journal of peritherapeutic neuroradiology, surgical procedures and related neurosciences. 2023 Dec:29(6):715-724. doi: 10.1177/15910199221110967. Epub 2022 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 35758285]

Chalouhi N, Dumont AS, Tjoumakaris S, Gonzalez LF, Bilyk JR, Randazzo C, Hasan D, Dalyai RT, Rosenwasser R, Jabbour P. The superior ophthalmic vein approach for the treatment of carotid-cavernous fistulas: a novel technique using Onyx. Neurosurgical focus. 2012 May:32(5):E13. doi: 10.3171/2012.1.FOCUS123. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22537122]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReis CV, Gonzalez FL, Zabramski JM, Hassan A, Deshmukh P, Albuquerque FC, Preul MC. Anatomy of the superior ophthalmic vein approach for direct endovascular access to vascular lesions of the orbit and cavernous sinus. Neurosurgery. 2009 May:64(5 Suppl 2):318-23; discussion 323. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000340781.34122.A2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19404110]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Keizer R. Carotid-cavernous and orbital arteriovenous fistulas: ocular features, diagnostic and hemodynamic considerations in relation to visual impairment and morbidity. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2003 Jun:22(2):121-42 [PubMed PMID: 12789591]