Introduction

Lumbar puncture (LP), also referred to as “spinal tap,” is a commonly performed procedure that involves obtaining and sampling cerebrospinal fluid from the spinal cord. It was developed by Heinrich Quincke in the late 19th Century.[1] It is the gold standard diagnostic procedure in the diagnosis of meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and certain neurological disorders. It is also used in the measurement of intracranial pressure and administration of medications or diagnostic agents.[2][3]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Understanding the anatomy of the lumbar spine is essential when performing a lumbar puncture. The order in which the spinal needle will traverse the lumbar spine is as follows:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous tissue

- Supraspinous ligament

- Interspinous ligament

- Ligamentum flavum

- Epidural space

- Dura

- Arachnoid

- Subarachnoid space

The distance from the skin to the epidural space is approximately 55 mm or 2/3 the length of the spinal needle.[4] The subarachnoid space is the area where the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample is obtained. During the advancement of the needle, a “pop” sensation is felt, which usually occurs during passage through the ligamentum flavum.[3]

Indications

A lumbar puncture may be indicated for both diagnostic and therapeutic reasons. The lumbar puncture may aid in the diagnosis of certain diseases that range from infectious (encephalitis, meningitis), inflammatory (multiple sclerosis and Guillain-Barre syndrome), and oncologic to metabolic processes. It may also aid in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. A lumbar puncture may also be indicated for the intrathecal administration of certain medications such as analgesics, chemotherapeutic agents, and antibiotics.[2]

Contraindications

Contraindications to performing a lumbar puncture include skin infection near or at the site of lumbar puncture needle insertion, central nervous system (CNS) lesion or spinal mass leading to increased intracranial pressure, platelet count less than 20,000 mm3 (ideally the platelet count should be greater than 50,000 mm3), use of unfiltrated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin in the past 24 hours, coagulopathies (i.e., hemophilia, von Willebrand disease) and vertebral trauma.[5]

A head computed tomogram (CT) should be obtained before performing a lumbar puncture if there is a concern for increased intracranial pressure. Signs and symptoms of possible increased intracranial pressure include altered mental status, focal neurological deficits, new-onset seizure, papilledema, immunocompromised state, malignancy, history of focal CNS disease (stroke, focal infection, tumor), concern for mass CNS lesion and age greater than 60 years old.[6]

Equipment

Lumbar puncture kits may vary slightly depending on manufacturer however the following should be included in all kits: spinal needle with a stylet (20 gauge or 22 gauge needle), four CSF collection vials, sterile drape, manometer with three-way valve, local anesthetic, syringes with needles (typically 18-gauge to draw up anesthetic and 25-gauge to inject into the skin), disinfecting solution (0.5% chlorhexidine/70% alcohol), sterile gloves, mask with face shield and surgical cap.[7] The use of a Whitacre spinal needle (pencil-point spinal needle) is recommended over a Quincke spinal needle (cutting spinal needle) as it results in fewer complications.[8] As the Whitacre spinal needle is pencil-point and considered an atraumatic needle, the skin must be punctured before needle insertion.

Personnel

The lumbar puncture is generally performed by one person. A second person, typically, a nurse (RN), may assist with the procedure. The person performing the lumbar puncture and the assistant should both be in sterile gowns and observe sterile precautions throughout the procedure.

Preparation

As with any procedure, preparation is key to ensure safety and improve the likelihood of success. First, begin by assessing whether there are any contraindications to performing the procedure. Clinical signs of or risk factors for increased intracranial pressure, coagulopathy, or thrombocytopenia should be evaluated before performing a lumbar puncture. Review the indications listed for head CT before performing a lumbar puncture (LP).

Before beginning, the procedure, as well as risks and benefits, should be explained to the patient. Informed consent should be obtained before performing the procedure.[9]

The positioning of the patient in either a lateral recumbent position or sitting position may be used. The lateral recumbent position is preferred as it will allow an accurate measurement of opening pressure, and it also reduces the risk of post-lumbar puncture headache. The patient should be instructed to assume the fetal position, which involves the flexion of the spine. It may be helpful to instruct the patient to flex their back "like a cat." By doing so, the space between the spinous processes increases, allowing for easier needle insertion. To help keep the needle at the midline during insertion, the lumbar spine should be perpendicular to the table in the sitting position and parallel to the table if in the recumbent position.

The ideal insertion point of the spinal needle should be either in the interspinous area between L4 and L5 or L3 and L4. Using these landmarks will avoid inadvertent damage to the conus medullaris, which typically terminates at L1. Palpation of landmarks along the back of the patient is used to locate the ideal insertion point for the needle. Certain conditions such as obesity, scoliosis, and degenerative disc disease may make palpation of landmarks more difficult. A line should be drawn between the superior aspects of the iliac crests. This line is referred to as the intercristal line or Tuffier line. This line typically intersects the spine along the L4 spinous process; however, this should only serve as a general reference as there are anatomical variations from person to person. The intercristal line may intersect at a higher level than L4 if the patient is female or obese.[10] Palpate the landmarks before cleaning the skin are and before administration of local anesthesia. Once the interspinous space is palpated, use a skin marking pen to mark the area of needle insertion.

The lumbar puncture is considered an aseptic procedure.[2] Wear sterile gloves and a gown, and clean the area with a disinfecting agent. The cleaning agent should be applied to the skin in a widening concentric circular fashion, starting at the point of needle insertion and circling outward. Allow the cleaned area to dry. Drape the area with sterile drapes.

Prepare CSF collection vials in order by labeling them according to the priority of collection. Typically they are labeled 1 through 4.

After the area has been cleansed and draped, apply a local anesthetic to the area of needle insertion. It is important to have marked the area of needle insertion before administration of local anesthetic as it may result in loss of landmarks.[11][12][13]

Technique or Treatment

Identify the anatomical landmarks once again before insertion of the spinal needle. The spinal needle should be inserted with the stylet in place and with the bevel in the sagittal plane. The bevel should face the ceiling if the patient is in the lateral decubitus position. This will spread the fibers of the cauda equina instead of cutting them during insertion. The fibers of the cauda equina run parallel to the spinal axis. Insert the needle in the midline at the superior aspect of the inferior spinous process. If inserting the needle in the L4-L5 interspace, the needle should be inserted along the superior aspect of the L5 spinous process. The needle should be inserted at an angle of approximately 15 degrees. It may be helpful to imagine aiming the needle towards the patient's umbilicus.

The needle should be inserted smoothly in a singular direction. There may be some minor resistance when passing through the ligamentum flavum, which may result in a "popping" sensation. After passing the ligamentum flavum, advance the needle in 2 mm increments each time removing the stylet to see if there is any CSF fluid draining. A standard Whitacre spinal needle will be inserted to approximately 2/3 depth before reaching the ligamentum flavum.[2] If a bone is encountered or there is no CSF fluid obtained, withdraw the needle to the subcutaneous tissue without exiting the skin, and redirect the needle. Do not redirect the needle while inserted beyond the subcutaneous tissue, as this will increase the risk of a traumatic lumbar puncture. A traumatic lumbar puncture will be tinged with blood. This typically occurs when the dorsal or epidural venous plexuses are pierced by the spinal needle.[14] If there is substantial blood present in the needle, it may become clogged. If this occurs, insert a new spinal needle at a different site. If unable to obtain CSF from the initial needle insertion site, an alternate site may be used. The use of ultrasound guidance has been shown to improve success rates.[15] An alternative technique known as the paramedian approach may be used to reach the subarachnoid space if the typical medial approach is unsuccessful. The point of needle entry is 1 cm inferior and 1 cm lateral to the typical L4 landmark. Needle insertion will be angled medially and cephalad at an angle of 15 degrees and advanced until CSF is obtained.[16][17]

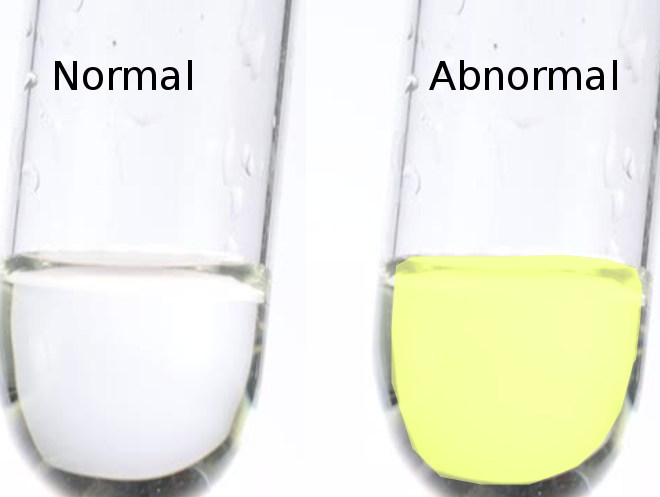

CSF fluid will flow once the subarachnoid space has been reached by the needle. If obtaining an opening pressure, ensure the patient is in the lateral decubitus position to ensure the readings will be accurate.[18] Attach the manometer to the spinal needle by using a flexible connector. Allow the CSF fluid level to rise in the manometer. Document the level at which the CSF fluid stops rising. Pulsatile variations may be present with the patient's respirations. Normal opening pressure ranges between 6 cm of water to 25 cm of water.[18] After obtaining and documenting the opening pressure, disconnect the tubing. Allow the CSF to drain passively from the needle hub into the collection vials. Do not aspirate the CSF fluid. For most routine diagnostic studies, collect approximately 1 mL per collection vial. After the collection of CSF fluid samples, replace the stylet into the spinal needle, and remove the needle. Apply gentle pressure with sterile gauze over the area where the needle was inserted. Cover the area with a small bandage.

Dispose of all sharps in the appropriate containers.[11][12][13]

Complications

Understanding the potential risks and complications associated with a lumbar puncture is of great importance and should be discussed with the patient before performing the procedure. Serious complications are rare, and risk can be minimized if proper technique and precautions are followed. The complications of a lumbar puncture include post-lumbar puncture headache, bleeding, infection, spinal hematoma, and cerebral herniation.[19] The most common complication observed after a lumbar puncture is a post-lumbar puncture headache.[20] Removal of the spinal needle with the stylet in place has been shown to reduce the incidence of post lumbar puncture headache.[21] Use of an atraumatic spinal needle (pencil-point spinal needle) and a smaller gauge is associated with fewer post-lumbar headaches as compared to cutting needle.[3][20]

Spinal hematoma is of particular concern in patients with coagulopathies or currently receiving certain anticoagulant medications.[14] If a spinal subarachnoid hematoma develops, the patient may complain of acute back pain or new neurologic symptoms. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain.[14]

Clinical Significance

Lumbar puncture is one of the most commonly performed procedures in the emergency department. It is used in the diagnosis of potentially life-threatening diseases such as meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage. A thorough understanding of anatomy, potential complications, and various techniques helps to ensure a successful and safe lumbar puncture. Maintaining open communication with the patient throughout the procedure may decrease patient anxiety and assist in first attempt success.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lumbar puncture is a commonly performed procedure in the emergency department and can be of great clinical importance when diagnosing potentially lethal diseases such as meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage. With proper preparation, technique, and care, the risks of complications can be significantly reduced. Mental visualization of the anatomical landmarks before insertion of the spinal needle will aid in the successful completion of a lumbar puncture. Informed decision making and discussion of risk-benefit with the patient will help reduce patient anxiety and lead to better outcomes.

Media

References

Pearce JM. Walter Essex Wynter, Quincke, and lumbar puncture. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1994 Feb:57(2):179 [PubMed PMID: 8126500]

Doherty CM, Forbes RB. Diagnostic Lumbar Puncture. The Ulster medical journal. 2014 May:83(2):93-102 [PubMed PMID: 25075138]

Wright BL, Lai JT, Sinclair AJ. Cerebrospinal fluid and lumbar puncture: a practical review. Journal of neurology. 2012 Aug:259(8):1530-45. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6413-x. Epub 2012 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 22278331]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHogan QH. Epidural anatomy: new observations. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 1998 May:45(5 Pt 2):R40-8 [PubMed PMID: 9599675]

Engelborghs S, Niemantsverdriet E, Struyfs H, Blennow K, Brouns R, Comabella M, Dujmovic I, van der Flier W, Frölich L, Galimberti D, Gnanapavan S, Hemmer B, Hoff E, Hort J, Iacobaeus E, Ingelsson M, Jan de Jong F, Jonsson M, Khalil M, Kuhle J, Lleó A, de Mendonça A, Molinuevo JL, Nagels G, Paquet C, Parnetti L, Roks G, Rosa-Neto P, Scheltens P, Skårsgard C, Stomrud E, Tumani H, Visser PJ, Wallin A, Winblad B, Zetterberg H, Duits F, Teunissen CE. Consensus guidelines for lumbar puncture in patients with neurological diseases. Alzheimer's & dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017:8():111-126. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.04.007. Epub 2017 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 28603768]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceApril MD, Long B, Koyfman A. Emergency Medicine Myths: Computed Tomography of the Head Prior to Lumbar Puncture in Adults with Suspected Bacterial Meningitis - Due Diligence or Antiquated Practice? The Journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Sep:53(3):313-321. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.04.032. Epub 2017 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 28666562]

Farley A, McLafferty E. Lumbar puncture. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987). 2008 Feb 6-12:22(22):46-8 [PubMed PMID: 18333557]

Xu H, Liu Y, Song W, Kan S, Liu F, Zhang D, Ning G, Feng S. Comparison of cutting and pencil-point spinal needle in spinal anesthesia regarding postdural puncture headache: A meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017 Apr:96(14):e6527. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006527. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28383416]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOrmerod V. Improving Patient Safety of Acute Care Lumbar Punctures. BMJ quality improvement reports. 2014:3(1):. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u203415.w2046. Epub 2014 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 26734272]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChakraverty R, Pynsent P, Isaacs K. Which spinal levels are identified by palpation of the iliac crests and the posterior superior iliac spines? Journal of anatomy. 2007 Feb:210(2):232-6 [PubMed PMID: 17261142]

Gorelick PB, Biller J. Lumbar puncture. Technique, indications, and complications. Postgraduate medicine. 1986 Jun:79(8):257-68 [PubMed PMID: 3520526]

Straus SE, Thorpe KE, Holroyd-Leduc J. How do I perform a lumbar puncture and analyze the results to diagnose bacterial meningitis? JAMA. 2006 Oct 25:296(16):2012-22 [PubMed PMID: 17062865]

Roos KL. Lumbar puncture. Seminars in neurology. 2003 Mar:23(1):105-14 [PubMed PMID: 12870112]

Park JH, Kim JY. Iatrogenic Spinal Subarachnoid Hematoma after Diagnostic Lumbar Puncture. Korean Journal of Spine. 2017 Dec:14(4):158-161. doi: 10.14245/kjs.2017.14.4.158. Epub 2017 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 29301177]

Soni NJ, Franco-Sadud R, Schnobrich D, Dancel R, Tierney DM, Salame G, Restrepo MI, McHardy P. Ultrasound guidance for lumbar puncture. Neurology. Clinical practice. 2016 Aug:6(4):358-368 [PubMed PMID: 27574571]

Janik R, Dick W. [Post spinal headache. Its incidence following the median and paramedian techniques]. Der Anaesthesist. 1992 Mar:41(3):137-41 [PubMed PMID: 1570886]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRabinowitz A, Bourdet B, Minville V, Chassery C, Pianezza A, Colombani A, Eychenne B, Samii K, Fourcade O. The paramedian technique: a superior initial approach to continuous spinal anesthesia in the elderly. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2007 Dec:105(6):1855-7, table of contents [PubMed PMID: 18042894]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLee SC, Lueck CJ. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in adults. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society. 2014 Sep:34(3):278-83. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000155. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25133881]

Sternbach G. Lumbar puncture. The Journal of emergency medicine. 1985:2(3):199-203 [PubMed PMID: 3833922]

Armon C, Evans RW, Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Addendum to assessment: Prevention of post-lumbar puncture headaches: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2005 Aug 23:65(4):510-2 [PubMed PMID: 16116106]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStrupp M, Brandt T, Müller A. Incidence of post-lumbar puncture syndrome reduced by reinserting the stylet: a randomized prospective study of 600 patients. Journal of neurology. 1998 Sep:245(9):589-92 [PubMed PMID: 9758296]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence