Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eye Lateral Rectus Muscle

Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eye Lateral Rectus Muscle

Introduction

The lateral rectus is one of the seven extraocular muscles. These muscles control every movement of the eye; usually, one muscle moves the eye in one direction, and the combination of all of them allows the eye to move in every direction. Extraocular muscles include four rectus muscles (medial, lateral, superior an inferior rectus), two oblique muscles (superior and inferior) and levator palpebrae superioris.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The lateral rectus muscle originates in the bottom of the orbital cavity in the surrounding area of the optic canal, specifically in the lateral part of the common tendinous ring; the annulus of Zinn. Almost every extraocular muscle originates in the annulus of Zinn, excluding inferior oblique muscle and levator palpebrae superioris. The lateral rectus is a flat-shaped muscle, and it is wider in its anterior part. The lateral rectus muscle is an abductor and moves the eye laterally, and side to side along with the medial rectus, which is an adductor.

Embryology

The lateral rectus muscles originate from mesoderm, like every extraocular muscle. One has to take into account all the connective tissue originates from neural crest cells. There are some cases studies in the literature where lateral rectus or other extraocular muscle have not developed well.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The extraocular muscles blood supply is variable. The lateral rectus blood supply depends on the muscular branches of the ophthalmic artery, as is the case for every extraocular muscle, and, additionally, receives one or two branches of the inferior muscular artery and the lacrimal artery. The lacrimal artery is a branch of the ophthalmic artery, which in turn is a branch of the internal carotid artery.

Veins are named like their counterpart arteries and drain into the superior and inferior orbital veins, located laterally and medially to the superior and inferior rectus muscle. These two veins drain to the cavernous sinus (sometimes directly and sometimes the inferior orbital veins drains into the superior orbital vein and then to the cavernous sinus.); the cavernous sinus drains into the inferior and superior petrosal sinus and then to the internal jugular vein.

Nerves

The lateral rectus is the only muscle supplied by cranial nerve VI, the abducens nerve, via the tectospinal tract.

Muscles

The rectus and extraocular muscles are different from other skeletal muscle of the human body; they consist of a selected variety of fibers types, which permit these muscles to make rapid (saccadic) movements and resist fatigue. The insertions of the rectus muscle are also much more precise than other muscle insertions; every one of these muscle originates at the annulus of Zinn, extends anteriorly and inserts on the globe at a specific distance from the limbus. For example, the lateral rectus muscle inserts about a 6.9mm from the limbus.

Along with the medial rectus, the lateral rectus forms the horizontal rectus muscle whereas superior and inferior rectus muscles form the vertical rectus muscles.

Physiologic Variants

Abnormal origin of the lateral rectus muscle is known to cause misalignment or strabismus. In addition, there are case reports of an absent lateral rectus muscle.

Surgical Considerations

Sometimes, it is necessary to correct strabismus surgically; by performing surgery, one can change the malalignment of the eye so that the patient can use both eyes together and reestablish their binocular function. Surgery can also improve the appearance of the eyes.

Because of the position of the nerve, it is sometimes possible for it to suffer damage during surgery; this can happen if the surgeon advances with the instruments about 3cm posterior to the insertion of the lateral rectus muscle.

The blood supply can also suffer damage during surgery. The blood vessels that supply lateral rectus muscle also provide blood to half of the anterior segment of the eye, specifically, the nasal half of the anterior segment. Thus, the surgeon has to be aware of the vascular supply to the lateral rectus muscle during surgery.[2]

Clinical Significance

Lateral rectus muscle abducts the eye and, consequently, allows people to look to the right with the right eye and to the left with the left eye. Clinicians usually test every extraocular muscle at the same time making the patient look in the nine directions with the eyes following the doctor’s finger or pen tracing an “H” form in the air.

Sometimes further tests, like cover-test, are needed to diagnose pathology of extraocular muscles.

The most common lateral rectus pathology encountered is a sixth nerve palsy, known as abducens palsy. In this case, the patient will not be able to abduct the eye and as a consequence, will experience diplopia or double vision. The diplopia will be binocular, meaning that if the patient covers one eye, he or she will not experiment double vision. Diplopia caused by lateral rectus muscle palsy gets worse when the clinician makes the patient look in the direction of the palsied muscle. For example, a case of right lateral rectus palsy, the patient will experience diplopia when looking to the right. Although complete lateral rectus palsy is easy to diagnose, sometimes microvascular damage to the nerve causes a “micro palsy,” where the patient seems to have the movements preserved but has double vision.[3]

The most common cause for sixth nerve palsy is microvascular or vascular damage to the nerve. However, tumor, infections, and inflammation could cause sixth nerve palsy too. The sixth cranial nerve is the most sensitive nerve to hydrocephalus,[4] and this condition should be suspected in any patient with bilateral lateral rectus palsy. Rarer causes of sixth nerve palsy include petrosal sinus thrombosis and autoimmune diseases.[5]

The literature has described lateral rectus myositis, which is a rare condition and usually reflects a rare inflammatory disorder. Lateral rectus muscle myositis may be a rare presentation of a non-Hodgkin B cell mucosa-associated lymphoma (MALT).

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

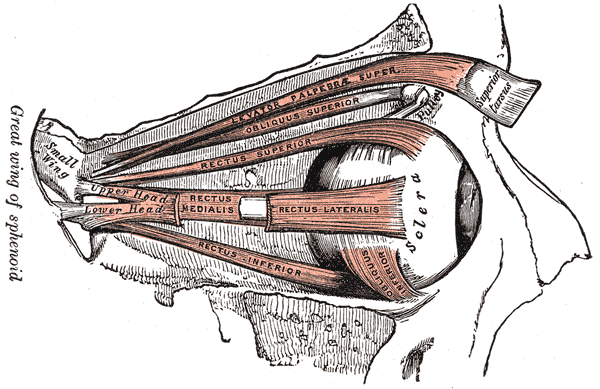

Orbital Muscles. This image shows the anatomical relationships between the levator palpebrae superioris, superior and inferior obliques, and superior, lateral, inferior, and medial recti. The sphenoid's greater wing, the sclera, and the superior tarsus are also referenced.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Bohnsack BL, Gallina D, Thompson H, Kasprick DS, Lucarelli MJ, Dootz G, Nelson C, McGonnell IM, Kahana A. Development of extraocular muscles requires early signals from periocular neural crest and the developing eye. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2011 Aug:129(8):1030-41. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.75. Epub 2011 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 21482859]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShumway CL, Motlagh M, Wade M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Eye Extraocular Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137849]

Elder C, Hainline C, Galetta SL, Balcer LJ, Rucker JC. Isolated Abducens Nerve Palsy: Update on Evaluation and Diagnosis. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2016 Aug:16(8):69. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0671-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27306521]

Nieto-Calvache AJ, Loaiza-Osorio S, Casallas-Carrillo J, Escobar-Vidarte MF. Abducens Nerve Palsy In Gestational Hypertension: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada : JOGC. 2017 Oct:39(10):890-893. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.04.031. Epub 2017 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 28602444]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMittal SO, Siddiqui J, Katirji B. Abducens nerve palsy due to inferior petrosal sinus thrombosis. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2017 Jun:40():69-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2017.02.018. Epub 2017 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 28242132]