Introduction

Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE) is an uncommon benign adnexal tumor originating from the hair follicle, first described by Zeligman in 1960 as a "solitary trichoepithelioma."[1] The lesion is classified into 3 subgroups: multiple familial trichoepithelioma, solitary nonhereditary trichoepithelioma, and desmoplastic trichoepithelioma.[2] In 1977, MacDonald et al referred to DTE as a "sclerosing epithelial hamartoma," and Brownstein and Shapiro later coined the term "desmoplastic trichoepithelioma," which remains in use today.[3][4]

Typically presenting as an asymptomatic annular, papular nodule with a "thread-like elevated border," DTE is usually <2 cm in diameter and commonly occurs in young to middle-aged women, particularly in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the cheeks, forehead, and chin.[1][5] Histopathologically, DTE is characterized by nests and cords of basaloid cells within a dense, fibrous stroma, occasionally containing small cystic spaces filled with keratinous material.[1] Peripheral palisading of cells is observed; significant mitotic activity is generally absent.[6] These features distinguish DTE from other skin neoplasms like basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and microcystic adnexal carcinoma, which exhibit more aggressive histologic features.[6]

Clinically, DTE manifests as a slow-growing, skin-colored facial plaque or nodule with a depressed center, developing very slowly before stabilizing.[7] Despite its benign nature and low risk of malignant transformation, DTE tends to grow if untreated and has a propensity for recurrence due to its poorly circumscribed histologic growth pattern.[8] Familial cases have been reported, suggesting a potential genetic predisposition.[9] Often an incidental finding during routine skin cancer examinations, DTE can frequently be diagnosed clinically by experienced dermatologists.[10] The preferred treatment is surgical excision, with Mohs micrographic surgery recommended to ensure clear margins, especially in cosmetically challenging areas like the face.[11]

DTE is a unique tumor due to its benign nature, distinct histopathological features, and superficial invasion. Accurate diagnosis relies on careful clinical and histopathological evaluation to distinguish it from more aggressive neoplasms.[12]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

DTE is a benign tumor with slow progression, typically developing over several years or even decades without a tendency to ulcerate.[6] The exact etiology of DTE remains unclear, but it is believed to arise from hair follicle structures, classifying it as an adnexal tumor. Unlike other skin tumors, there is no strong association with ultraviolet radiation or apparent environmental factors.

Chromosomal mutations, particularly on 9p21 and 16q12-q13, significantly contribute to the development of DTE, indicating a genetic basis for the condition.[7] Familial forms of DTE, though much rarer, result from an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by a positive family history and multiple papules or nodules.[6] Affected individuals may have a family history of multiple trichoepitheliomas or syndromes like Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Notable cases include a mother and 2 daughters developing facial lesions and a mother and son exhibiting multiple lesions on the scalp and face.[13] Despite the genetic predisposition, the exact mechanism through which these mutations lead to tumor formation is not fully understood. Sporadic mutations are likely responsible for the majority of DTE cases. There is usually no associated systemic disease with DTE, and the tumor's development is typically localized to the skin.[6]

Epidemiology

DTE has an incidence of approximately 2 per 10,000 individuals, accounting for <1% of all cutaneous tumors.[7] DTE exhibits a bimodal age distribution, commonly occurring in young children and middle-aged adults around 45 years.[6] Studies show that DTE typically appears from birth to the fourth decade of life, though recent cases have been reported in patients ranging from 8 to 79 years of age.[1] DTE commonly exhibits a slow growth pattern with no discernible inheritance pattern. The tumor predominantly affects females, with a strong predominance of approximately 85%.[6]

Pathophysiology

DTE is an adnexal tumor originating from follicular germinative cells, characterized by the proliferation of basaloid cells within a densely fibrotic stroma that can differentiate into numerous parts of the folliculosebaceous apocrine complex.[14] Histologically, DTE presents with tiny strands of basaloid cells, keratinous cysts, and calcifications, demonstrating follicular differentiation.[7] Immunohistochemically, DTE shows CD34-positive stromal cells and CK20-positive Merkel cells within tumor nests, supporting its follicular origin and aiding in differentiation from other neoplasms, such as BCC.[2][7] While most cases of DTE are sporadic, there have been reports of familial cases involving both solitary and multiple lesions.[15]

Histopathology

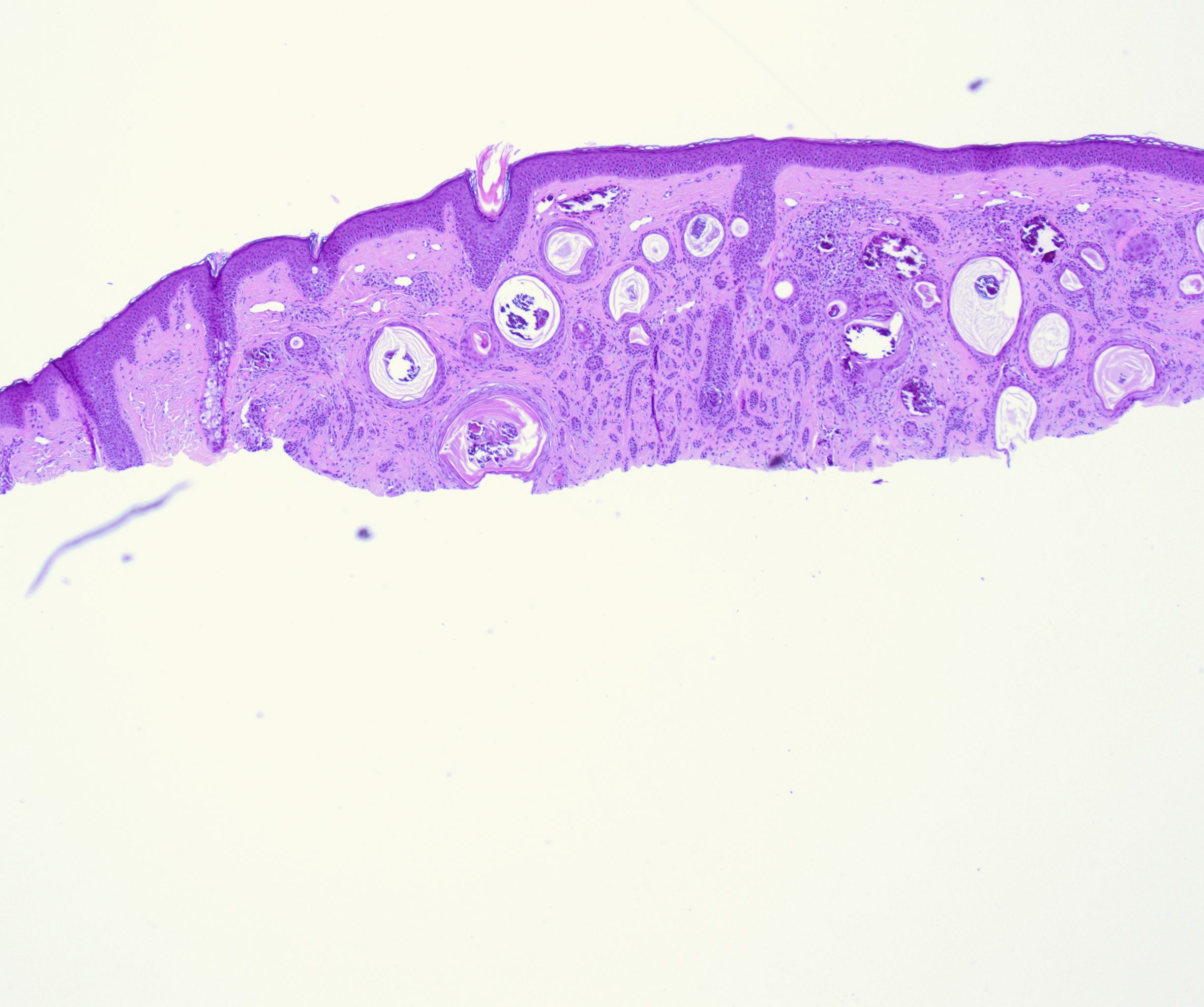

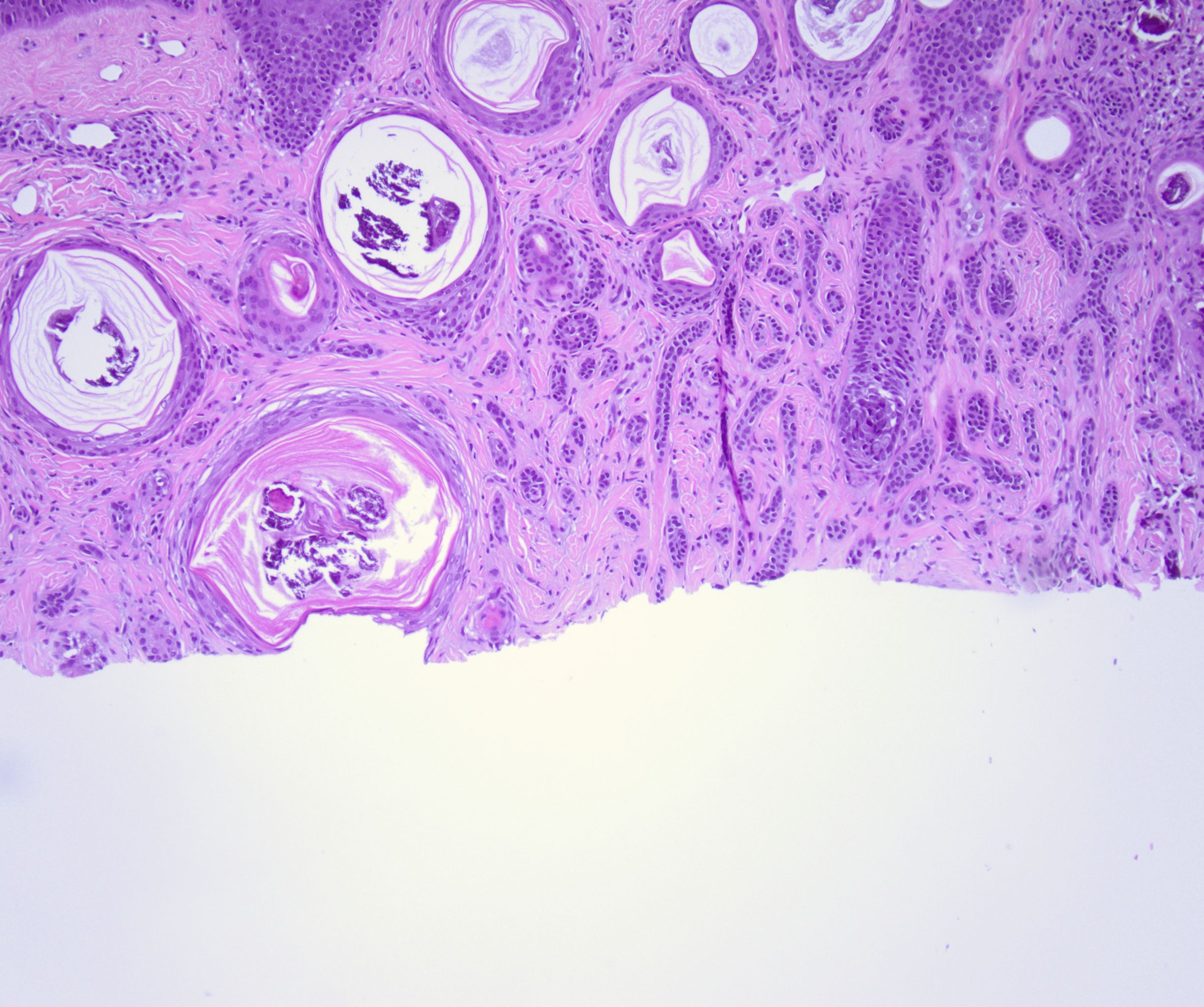

Histologically, DTE is characterized by a triad of features: narrow strands of basaloid tumor cells, keratinous cysts, and desmoplastic stroma, a combination that has remained the hallmark of DTE since Brownstein and Shapiro's study (see Image. Histopathology of a Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma at Low Power).[7] The basaloid tumor cells are arranged in strands 1 to 3 cells thick, with small, prominent oval nuclei and minimal cytoplasm.[1] These basaloid cells form slender strands or cords with peripheral palisading and typically exhibit no mitotic figures, pleomorphism, or apoptotic activity.[10] Keratinous cysts represent cystic spaces containing keratinaceous material lined by stratified squamous epithelium, sometimes with calcification, indicating differentiation toward hair structures.[4] Additionally, slightly refractile "shadow" cells with keratolysis can be seen in the cysts' epithelial lining.[1] Surrounding these structures is a densely collagenous and hypocellular stroma.[4][11]

DTE tumors are usually well-circumscribed, symmetrical, and confined to the papillary dermis and the upper two-thirds of the reticular dermis, seldom reaching the lower dermis or subcutaneous fat (see Image. Histopathology of a Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma at Medium Power).[16] Foreign body granulomas, calcification, ossification, and acantholysis are frequently observed.[4] A key distinguishing feature is the lack of loose stroma and large tumor cell masses histologically seen in other tumors like conventional trichoepithelioma.[1] Although DTE can invade perineural and intraneural regions, this is not specific to DTE and can also be seen in other skin tumors.[1]

Immunohistochemically, DTE can stain positive for CK20, BerEP4, PHLDA1, CK15, and CD34, aiding in its differentiation from other neoplasms, such as BCC, which may present similarly but have different treatment implications.[5][7] CD34-positive stromal cells are particularly indicative of the desmoplastic stroma in DTE.[6] Accurate diagnosis is crucial to avoid overtreatment or mismanagement, emphasizing the importance of recognizing these histological and immunohistochemical features in clinical practice.

History and Physical

DTE is more frequently observed in females and generally appears as a single lesion, though multiple lesions can occur in rare cases.[7] The lesion exhibits a bimodal age distribution, commonly affecting both young children and adults, with a notable occurrence in middle-aged individuals around 45 years.[6] Patients often report that lesions are present for many years, with a slow but steady growth pattern, but most are present for less than 5 years.[1][15]

The lesions are characterized by a raised annular border and a depressed, nonulcerating center, sometimes accompanied by a ring of papules or milia-like components.[4] Although typically asymptomatic, the cosmetic appearance and potential for facial disfigurement are significant concerns for patients.[1] DTE lesions are often discovered incidentally during routine skin examinations and may remain stable without significant changes for extended periods.[5] Overall, DTE exhibits benign behavior with slow progression, with rare reports of aggressive behavior such as ulceration or recurrence likely attributable to misdiagnosed follicular tumors.[1]

DTE exhibits distinct dermoscopic features that aid in its differentiation from other similar lesions. The dermoscopic features specific to DTE include an ivory white background, prominent arborizing telangiectasias, and numerous white clods corresponding histologically to keratin cysts and desmoplastic stroma.[16][17] Shiny white linear structures resembling "chrysalides" may also be present under dermoscopy.[6] Unlike BCC, DTE does not display pigmented structures such as "maple leaf" patterns or "gray-blue ovoid nests."[6] The presence of discrete white circular structures, which enhance under nonpolarized light, is common in adnexal tumors like DTE and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. These white structures likely represent keratin cysts and calcification within the tumor.[18] In some cases, an erythematous background with white dots has been observed, which may indicate an early phase of progressing desmoplastic stroma, particularly in patients of color.[19]

Additionally, confocal laser reflectance microscopy can be helpful in analyzing DTE, providing detailed visualization of the keratin-filled cysts and confirming the dermoscopic findings.[6] The combination of these dermoscopic features, particularly the ivory white background and arborizing telangiectasias, is pathognomonic for DTE and assists in distinguishing it from other skin lesions.[19]

Evaluation

DTE is sometimes diagnosed through clinical evaluation alone, potentially avoiding the need for a skin biopsy. However, a skin biopsy is essential for a definitive diagnosis when the lesion's morphology, location, or changes raise suspicion.[10] DTE can mimic other benign and malignant tumors, such as morpheaform BCC, syringoma, conventional trichoepithelioma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma, making diagnosis challenging even for experts.[7] Combining clinical and histological findings may still result in misdiagnosis, underscoring the importance of thorough evaluation.[20]

A full-thickness biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis, as small or incomplete biopsies can lead to diagnostic uncertainty due to the histopathological similarities between DTE and other tumors. In such cases, resampling or re-excision may be necessary.[5] The pathology report is essential to determine whether the lesion should be surgically removed or managed conservatively. Histopathological examination reveals basaloid cells among thick collagen bundles with keratin plugs, helping distinguish DTE from other malignancies. Immunohistochemistry markers can further aid in confirming the diagnosis of DTE, especially in complex cases.[7][21]

Optional noninvasive imaging techniques like dermoscopy, reflectance confocal microscopy, and high-definition optical coherence tomography have emerged, enhancing the accuracy of in vivo diagnosis and sometimes avoiding invasive biopsy.[22] These imaging modalities provide detailed visualization of the tumor's structural features, aiding in differentiation from similar tumors by highlighting specific characteristics such as low-reflective dermal tumor islands and surrounding reflective collagen.[22]

Integrating clinical features with histopathological and imaging findings is crucial for an accurate diagnosis. By considering all of these aspects, dermatologists can ensure effective diagnosis and management of DTE.[7][10]

Treatment / Management

While most DTEs grow slowly and may stabilize without intervention, some cases present diagnostic challenges and may require a more invasive approach to management.[10] A thorough diagnostic evaluation involving a full-thickness biopsy is critical in these instances. A biopsy allows for accurate histopathological examination, differentiating DTE from malignant conditions and pointing clinicians toward a specific pathology for treatment. Current options for treating DTE include observation, dermabrasion, laser surgery, excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery.[23]

Given that DTE is a slow-growing, benign tumor, observation is a potential option, especially for lesions in children.[21] There have been cases of DTEs stabilizing without any treatment and even having spontaneous improvement.[10][21] Despite its benign nature, DTE has the potential to exhibit aggressive histologic features and penetrate deeply, necessitating precise excision techniques.[1] DTE is most commonly managed through surgical excision, with Mohs micrographic surgery often being the preferred method, especially for lesions on the face.[7] Mohs micrographic surgery ensures clear margins and reduces the risk of local recurrence, which is crucial given the tumor's propensity for cosmetically sensitive areas.[5][7](B3)

There is a well-known debate within the medical community regarding the necessity of Mohs micrographic surgery for DTE cases. Suggesting that all DTEs should be removed with Mohs micrographic surgery can be considered an overly aggressive approach for a benign tumor, the majority of which will cause no harm.[10] Some experts argue that conservative management, including observation, may be appropriate for many patients, especially given the slow growth and benign nature of most DTEs.[10] However, given the potential for misdiagnosis and the occurrence of DTEs in cosmetically sensitive areas, Mohs micrographic surgery is often advocated as the treatment of choice to prevent recurrence and ensure clear margins.[12] (A1)

Complete excision is recommended to exclude malignancy and prevent possible malignant transformation in cases with multiple lesions or any diagnostic uncertainty.[7] Techniques like curettage, dermabrasion, laser surgery, and observation are treatment options typically reserved for less ambiguous cases or those not located in sensitive areas.[21](B3)

Overall, the management of DTE should be tailored to the individual patient, considering factors such as lesion location, growth behavior, and diagnostic clarity. A comprehensive discussion with the patient about various treatment options and their potential risks and benefits is essential to ensure optimal outcomes.[15] Long-term follow-up is highly recommended to monitor for recurrence, particularly in cases with a high risk of cosmetic disfigurement.[12] In any case of diagnostic doubt, excision should be performed, with Mohs micrographic surgery as the recommended excision technique.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of DTE is particularly challenging due to its histopathological similarities with other skin lesions, most importantly, syringoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, BCC (eg, morpheaform BCC), and cutaneous metastatic breast cancer.[7] Differentiating DTE from other skin lesions involves a detailed clinical and histopathological examination. Due to the superficial nature of some biopsy specimens, re-excision or resampling may be necessary to make a definitive diagnosis.[1]

DTEs and BCCs share certain dermoscopic features, including arborizing telangiectasias and crystalline structures; however, cyst-like structures are more suggestive of DTE.[5] The absence of surface telangiectasias and a thin epidermis can aid in differentiating DTE from BCC.[1] Histologically, DTE lacks atypia, large tumor masses, and peripheral palisading, features common in BCCs.[11] DTE and infiltrative BCC share histomorphological features, such as small strands of basaloid cells within a sclerotic stroma.[2] Reliable criteria distinguishing DTE from infiltrative BCC include architectural symmetry, well-circumscribed lesions, central depression, connection to infundibula, granulomatous giant cell reaction due to ruptured keratinous cysts, foci of calcification and ossification, absence of tumor-stroma clefting and solar elastosis, and association with melanocytic nevus.[2]

The most significant histologic differential diagnosis for DTE is morpheaform BCC, which shares similar features but is often asymmetrical, lacks horn cysts and shows cellular atypia and peripheral palisading, which are absent in DTE.[11] Immunohistochemical markers also help distinguish between DTE and morpheaform BCC. CD34-positive spindle cells surround DTE but do not surround morpheaform BCC, and DTE shows retained or increased CK20-positive Merkel cells, unlike morpheaform BCC.[20] Furthermore, the Bcl-2 stain has been found to stain more diffusely in morpheaform BCC than in DTE but is not a reliable marker.[1] The AR-negative, CK20-positive phenotype is sensitive and specific for DTE, while the AR-positive, CK20-negative phenotype is specific for BCC.[7] Other markers, such as PHLDA1, help differentiate DTE from nonulcerated BCCs, with PHLDA1 staining positive in DTE.[7]

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma can resemble DTE on physical examination and under the microscope and must be included in the differential diagnosis of DTE.[1] Clinically, microcystic adnexal carcinoma presents as a slowly growing plaque or nodule, often on the face, and is distinguished from DTE by its diffuse infiltration into the subcutis with perineural invasion and the expression of markers such as CK19 and Ber-EP4/EpCAM.[7] Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is typically asymmetric, has frequent ductal structures, is poorly circumscribed, and extends beyond the reticular dermis.[20] Therefore, when a biopsy is superficial, microcystic adnexal carcinoma can commonly be misdiagnosed as DTE.[11]

A syringoma, which lacks cornified cysts or calcifications, typically presents with multiple lesions, often in the periorbital region, contrasting with the solitary nature of DTE.[6][20] Syringomas exhibit distinct narrow strands of tumor cells that show ductal differentiation, while DTEs exhibit continuous strands with horn cysts and hyperplasia of the epidermis.[7] The CK20 marker is nearly always positive in DTE but rarely or never in syringoma, while DTE is negative for carcinoembryonic antigen, unlike syringoma.[20]

Breast cancer has the potential to present with cutaneous manifestations, either in the form of skin metastases or direct tumor extension, and it can sometimes be challenging to differentiate DTE from cutaneous metastatic breast cancer.[7] Cutaneous metastatic breast cancer, which typically involves the chest, can be differentiated from DTE by its location, histological features, and strong positivity for pan-cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen.[7] Histological characteristics of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer include glandular patterns, single-file line patterns of malignant cells between collagen fibers, lymphatic embolization by cancerous cells, and fibrotic and epidermotropic patterns.[7]

Other less frequently discussed conditions that mimic DTE's clinical and histological features include sebaceous hyperplasia, granuloma annulare, scar tissue, and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.[20] Overall, the differentiation of DTE requires a combination of clinical presentation, histological examination, and immunohistochemical staining to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.[2]

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Recent studies on DTE have focused on improving diagnostic accuracy and understanding its clinical behavior. Advances in dermatoscopy and histopathological techniques have aided in better differentiating DTE from other skin lesions, particularly BCC, which it often mimics. Molecular and genetic studies are also shedding light on the potential hereditary patterns in familial cases of DTE, although the tumor remains overwhelmingly sporadic. New research on immunohistochemical markers has helped refine diagnostic criteria, providing better tools for pathologists. These studies underscore the importance of continuous advancements in diagnostic techniques to improve outcomes for patients with DTE.

Prognosis

DTE has an excellent prognosis due to its benign nature.[2] Accurate diagnosis is critical as it influences the treatment approach and prognosis compared to other tumors that mimic DTE, which may require more aggressive management.[7] Despite its aggressive histological features that can cause diagnostic uncertainty, DTE does not metastasize and has a very favorable outcome with low recurrence rates after complete surgical excision.[7] Differentiation from other structurally similar but biologically distinct tumors is essential and involves a detailed histopathological examination, immunohistochemical staining, and correlation with clinical findings to ensure precise identification and appropriate management.[7]

Regular follow-up is recommended to monitor for any signs of recurrence, although rare.[7] Patient education regarding the benign nature of DTE and the importance of routine dermatological check-ups can help alleviate anxiety and ensure ongoing monitoring. By maintaining vigilance in follow-up and patient counseling, health care professionals can ensure optimal long-term outcomes for patients with DTE.

Complications

DTE is generally benign, but its complications primarily stem from diagnostic challenges and potential mismanagement. Due to its histopathological similarities to more aggressive tumors, DTE can be misdiagnosed, leading to unnecessary aggressive treatments such as extensive surgical excisions.[7] Conversely, if a malignant tumor is incorrectly diagnosed as DTE, there may be a delay in appropriate treatment, potentially worsening the patient's prognosis.

The dense stromal desmoplasia and basaloid cell strands in DTE complicate its distinction from other adnexal tumors, often necessitating comprehensive histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluations to avoid diagnostic pitfalls.[1][2] These diagnostic complexities underscore the importance of accurate identification and appropriate clinical management to prevent potential overtreatment or undertreatment.[7]

Incomplete excision of DTE, especially when not recognized as benign, can result in local recurrence due to its poorly circumscribed growth pattern. Additionally, surgical removal of DTE, particularly from cosmetically sensitive areas like the face, may lead to scarring or disfigurement, emphasizing the need for careful diagnosis and precise surgical techniques like Mohs micrographic surgery.

Consultations

Patients with DTE often require consultations with various specialists to ensure accurate diagnosis and effective management. A dermatologist is typically the first to evaluate the lesion, and their expertise is crucial for identifying suspicious features and guiding the need for a biopsy. Pathologists play a pivotal role in distinguishing DTE from other similar neoplasms, such as BCC, through histopathological examination, often using immunohistochemical markers. In cases requiring surgical intervention, particularly when the tumor is located in cosmetically sensitive areas like the face, consultation with a dermatologic surgeon or plastic surgeon is essential to ensure precise excision while minimizing scarring and recurrence. In some cases, a geneticist may be consulted for familial or multiple lesions. Primary care physicians may also be involved in long-term follow-up and care coordination, ensuring comprehensive management and patient education.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education are critical components in the management of DTE. Given its benign nature and favorable prognosis, patients should be reassured about the nonaggressive behavior of DTE. Educating patients about the importance of distinguishing DTE from similarly appearing skin lesions, such as BCC, is vital to avoid unnecessary anxiety and overtreatment.[7] Patients should be informed about the typical clinical presentation of DTE, including its appearance as a small, firm, annular papule, often with a central depression.[1] Regular dermatologic evaluations and monitoring of skin lesions are recommended to ensure early and accurate diagnosis. Patients should also be educated on the importance of seeking evaluation from a dermatology expert when new or changing skin lesions are observed. Clear communication about the benign prognosis of DTE and the importance of differential diagnosis can improve patients' engagement in their care.[2]

Pearls and Other Issues

When diagnosing and managing DTE, several key insights can aid in clinical decision-making, which include the following:

- DTE commonly presents as a small, firm, skin-colored nodule with a "thread-like" raised border, typically located on the face, particularly the cheeks, forehead, and chin.

- DTE is most prevalent in young to middle-aged women and is slow-growing, usually less than 2 cm in diameter.

- Histopathologically, DTE is characterized by nests and cords of basaloid cells in a dense, fibrotic stroma, often with peripheral palisading and occasional keratin-filled cysts.

- Critical differential diagnoses include BCC and microcystic adnexal carcinoma; biopsy and histopathology are essential for accurate differentiation.

- Though benign, incomplete excision can lead to recurrence, making Mohs micrographic surgery the preferred treatment in cosmetically sensitive areas.

- DTE has a low risk of malignant transformation but should be monitored in familial cases with possible genetic predisposition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An effective interprofessional team plays a vital role in delivering patient-centered care, improving outcomes, and ensuring safety for individuals with DTE. Each team member contributes distinct skills and responsibilities, and effective communication is key to optimizing care coordination.

Physicians, particularly dermatologists and pathologists, need diagnostic expertise, utilizing clinical evaluation and histopathology to distinguish DTE from malignancies.[1] Dermatologic surgeons bring surgical skills, often employing techniques like Mohs micrographic surgery to minimize recurrence and scarring. Advanced practitioners collaborate with physicians to assess, diagnose, and manage patients. They may assist in biopsies, provide patient education, and support decision-making. Nurses play a key role in patient education and care coordination, assisting with preoperative and postoperative procedures, monitoring for complications, and ensuring adherence to follow-up plans. Nurses act as liaisons between patients and other health care professionals, enhancing care continuity and patient safety through effective communication. Pharmacists may manage postoperative medications, particularly guiding analgesics or antibiotics, ensuring patient safety by reviewing interactions and adverse effects.

Effective interprofessional communication is critical for optimal team performance. Regular case discussions, shared patient records, and transparent communication channels help avoid missteps, ensure accurate diagnosis, and provide a comprehensive treatment plan. Clear, consistent messaging to the patient ensures informed consent and enhances patient satisfaction.

Care coordination is especially important in cases requiring surgical intervention, where multiple appointments and follow-ups are involved. Each team member must work collaboratively to ensure seamless transitions between diagnostic, therapeutic, and follow-up phases, thereby improving patient-centered care and outcomes.[7]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mamelak AJ, Goldberg LH, Katz TM, Graves JJ, Arnon O, Kimyai-Asadi A. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010 Jan:62(1):102-106. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.06.066. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20082889]

Bartoš V. Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma: An Uncommon but Diagnostically Problematic Benign Adnexal Tumor. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC. 2019 Dec:27(4):282-284 [PubMed PMID: 31969246]

Macdonald DM, Jones EW, Marks R. Sclerosing epithelial hamartoma. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 1977 Jun:2(2):153-60 [PubMed PMID: 884894]

Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Cancer. 1977 Dec:40(6):2979-86 [PubMed PMID: 589563]

Phillips D, Chaudhry IH, Morton JD, West EA. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: an uncommon adnexal tumour with a predilection for cosmetically sensitive sites. British journal of hospital medicine (London, England : 2005). 2022 Jul 2:83(7):1-3. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2021.0437. Epub 2022 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 35938754]

Huet P, Barnéon G, Cribier B. [Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: The correlation between dermatopathology and dermatoscopy]. Annales de dermatologie et de venereologie. 2019 Nov:146(11):760-763. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2019.09.001. Epub 2019 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 31601440]

Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, Murtazaliev S, Sonawane S. Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma: Histopathologic and Immunohistochemical Criteria for Differentiation of a Rare Benign Hair Follicle Tumor From Other Cutaneous Adnexal Tumors. Cureus. 2020 Aug 12:12(8):e9703. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9703. Epub 2020 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 32923292]

Mohanty SK, Sardana R, McFall M, Pradhan D, Usmani A, Jha S, Mishra SK, Sampat NY, Lobo A, Wu JM, Balzer BL, Frishberg DP. Does Immunohistochemistry Add to Morphology in Differentiating Trichoepithelioma, Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma, Morpheaform Basal Cell Carcinoma, and Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma? Applied immunohistochemistry & molecular morphology : AIMM. 2022 Apr 1:30(4):273-277. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000001002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35384877]

Lovgren ML, Rajan N, Joss S, Melly L, Porter M. Inherited desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2019 Oct:44(7):e238-e239. doi: 10.1111/ced.13876. Epub 2019 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 30697781]

Moynihan GD, Skrokov RA, Huh J, Pardes JB, Septon R. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011 Feb:64(2):438-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.053. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21238832]

Moon SH, Choi HS, Kwon HI, Ko JY, Kim JE. A Case of Multiple Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma. Annals of dermatology. 2016 Jun:28(3):411-3. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.3.411. Epub 2016 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 27274652]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNanda R, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. A Systematic Review of the Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, Treatment, and Outcomes for Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma: Underscoring Mohs Micrographic Surgery in Management. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2024 Aug 1:50(8):695-698. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000004194. Epub 2024 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 38595132]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCarter JJ, Kaur MR, Hargitai B, Brown R, Slator R, Abdullah A. Congenital desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2007 Sep:32(5):522-4 [PubMed PMID: 17459070]

Matsuki T, Hayashi N, Mizushima J, Igarashi A, Kawashima M, Harada S. Two cases of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. The Journal of dermatology. 2004 Oct:31(10):824-7 [PubMed PMID: 15672712]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShehan JM, Huerter CJ. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: report of a case illustrating its natural history. Cutis. 2008 Mar:81(3):236-8 [PubMed PMID: 18441846]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhelifa E, Masouyé I, Kaya G, Le Gal FA. Dermoscopy of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma reveals other criteria to distinguish it from basal cell carcinoma. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2013:226(2):101-4. doi: 10.1159/000346246. Epub 2013 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 23363889]

Kunz M, Kerl K, Braun RP. Basal Cell Carcinoma Mimicking Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma: A Case with Correlation of Dermoscopy and Histology. Case reports in dermatology. 2018 May-Aug:10(2):133-137. doi: 10.1159/000489164. Epub 2018 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 29928202]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCostello CM, Han MY, Severson KJ, Maly CJ, Yonan Y, Nelson SA, Swanson DL, Mangold AR. Dermoscopic characteristics of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma. International journal of dermatology. 2021 Mar:60(3):e83-e84. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15040. Epub 2020 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 32686120]

Twaseem PM, Criton S, Abraham UM, Francis A. A Case of Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma with a New Dermoscopy Finding. Indian journal of dermatology. 2022 Sep-Oct:67(5):589-590. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_1000_21. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36865851]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang Q, Ghimire D, Wang J, Luo S, Li Z, Wang H, Geng S, Xiao S, Zheng Y. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: A clinicopathological study of three cases and a review of the literature. Oncology letters. 2015 Oct:10(4):2468-2476 [PubMed PMID: 26622873]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNuno-Gonzalez A, Colmenero I, de Prada I, Noguera-Morel L, Martorell-Calatayud A, Hernandez-Martin A, Torrelo A. Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma: An Infrequent Entity not to be Missed: Report of Two Cases. Pediatric dermatology. 2015 Sep-Oct:32(5):e208-9. doi: 10.1111/pde.12622. Epub 2015 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 26060036]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOliveira A, Arzberger E, Zalaudek I, Hofmann-Wellenhof R. Imaging of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2015 Apr:41(4):522-5. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000311. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25775446]

Singh S, Rapini R, Schwartz M, Friedman-Musicante R, Friedman PM. Challenging the dogma of "watchful waiting" for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2013 Mar:39(3 Pt 1):483-6. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12051. Epub 2012 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 23279599]