Introduction

Corticobulbar tract supplies upper motor neuron innervation to the cranial nerves supplying head and face. The precentral gyrus in the posterior part of the frontal lobe of the cerebrum is the part of the primary motor cortex from where several motor pathways originate. Some fibers to cortico-bulbar tract (as with corticospinal tract) also come from the Pre-motor area and supplementary area.

The corticobulbar tract starts in the precentral gyrus. From here, the corticobulbar fibers pass through the corona radiata, genu of the internal capsule, peduncle of the cerebrum, base of the pons, and then to the medullary pyramid. They synapse at the motor nuclei of cranial nerve nuclei. The corticobulbar tract may synapse either directly on the motor nuclei or indirectly through interneurons. Corticobulbar tract supplies input bilaterally to trigeminal, facial, and hypoglossal nerve nuclei.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Cell bodies of these neurons are situated mainly in the Broadman’s areas number 4, 6. The organization of the motor cortex is in a somatotopic manner. Cortical homunculus is a map of the representation of different parts of the body in specific areas of the motor cortex with face situated most laterally.

From the cerebral cortex, the corticobulbar fiber passes into the corona radiata. Most of the fibers of corona radiata arrange themselves into a compact bundle called the internal capsule, which is situated between caudate nucleus and thalamus medially and lentiform nucleus laterally. Corticobulbar fibers pass through the genu or bend of the internal capsule. From the internal capsule, these fibers enter into crus cerebri of the cerebral peduncles in the midbrain. Corticobulbar fibers pass through middle 1/3 of crus cerebri and then enter the pons and medulla to terminate at corresponding nerve nuclei.

The corticobulbar tract provides input to the nuclei innervating muscles of the face, muscles of mastication, muscles of the tongue, muscles of the pharynx, muscles of larynx, sternocleidomastoid, and trapezius, etc. This innervation is bilateral for most of the cranial nerves, with the exception of corticobulbar fibers providing input to the lower facial nucleus, which receives contralateral innervation. Both right and left half of the motor cortex of the brain gives fibers to the dorsal division of the motor nucleus of the facial nerve ( bilateral innervation), but the lower division of facial nerve nucleus receives unilateral upper motor neuron fibers. The dorsal division of the facial nerve nucleus gives lower motor neuron fibers to the upper half of the face, and the lower half of the face receives fibers from the ventral division of the facial nerve nucleus.[1][2][3][4]

Embryology

The cerebral hemisphere forms from the telencephalon. The cerebral cortex forms from the roof and lateral aspect of telencephalon forming cerebral hemisphere. Initially, no sulci, gyri are present, but after six months of intrauterine life, sulci and gyri start appearing. The precentral gyrus forms in front of central sulcus. Cranial nerve motor nuclei formed from the basal plate of the brain stem. Processes of neurons situated in percental gyrus terminating at cranial nerve nuclei directly or indirectly through interneuron form corticobulbar tract.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Corticobulbar tact receives supply from branches of the middle cerebral artery, anterior cerebral artery, and basilar artery.[6]

Thrombosis, embolism, rupture, trauma, or compression of a blood vessel supplying genu of the internal capsule can cause injury to corticobulbar and adjacent tracts. As in the internal capsule, tracts are closely packed, infarction of small areas can lead to damage of several descending and ascending tracts.

Muscles

Corticobulbar tract carries upper motor neuron input to motor nuclei of trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory, and hypoglossal nerves. The motor component of trigeminal nerves supplies muscles of mastication. The facial nerve supplies the muscles of facial expression. Glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory nerve innervates muscles of the pharynx, muscles of larynx, sternocleidomastoid, and trapezius muscle. Tongue muscles receive fibers from the hypoglossal nerve.

The corticobulbar tract indirectly affects muscles supplied by third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve through medial longitudinal fasciculus and paramedian part of the pontine formation.

Physiologic Variants

The corticobulbar tract extends from the precentral cortex to cranial nerve nuclei supplying the head and neck region. Similarly, upper motor fibers for the body are carried by the corticospinal tract, which connects the cerebral cortex to the spinal cord.[3]

Surgical Considerations

Injury to corticobulbar tract between the cerebral cortex and brain stem leads to symptoms of upper motor neuron damage of cranial nerves supplying the face, head, and neck. Common causes of damage to the corticobulbar tract are cerebrovascular accidents, space-occupying lesions, trauma, degenerative diseases of the brain, etc. Symptoms of corticobulbar fiber lesion are dysarthria, dysphagia, difficulty in the jaw and facial movements, spasm of the tongue, and increased reflex.[7][8]

Clinical Significance

Pseudobulbar palsy is a condition in which there is bilateral damage to corticobulbar fibers leading to dysarthria, dysphagia, spasticity of the tongue, hyperreflexia, and difficulty with jaw and facial movements. The pseudobulbar impact of the labile effect is a common symptom of pseudobulbar palsy. The pseudobulbar affect or labile effect characteristically presents as an episode of emotional imbalance (excessive crying or laughing).[9][10]

Pseudobulbar palsy can be due to multiple reasons such as:

- Infarction of cerebral hemisphere bilaterally

- Demyelinating motor neuron disease

- Tumors in the upper part of the brain stem

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Parkinson’s Disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- Trauma

If there is damage to the corticobulbar tract of one side anywhere between precentral gyrus to the motor nucleus of the facial nerve. It results in paralysis of muscles of the opposite lower half of the face.

For example- If a corticobulbar tract of right side carrying fibers to the facial nucleus gets damaged, facial muscles of the lower half of the face on the left side get paralyzed. Muscles of the upper half of the left side remain unaffected as it receives innervation from corticobulbar fibers of facial nerve of both sides.

Supranuclear lesions of the hypoglossal nerve can occur at any site extending from the cerebral cortex to hypoglossal nerve nuclei. Tongue atrophy does not occur in supranuclear lesions, but it can lead to uncoordinated, slow but spastic tongue movements. Infranuclear lesions of hypoglossal nerve cause weakness, ipsilateral atrophy of the tongue with fasciculations.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a disease in which there is the progressive degeneration of neuronal tissue. When degeneration involves corticobulbar tract signs and symptoms of upper motor neuron disease in the form of muscular weakness, difficulty in speech, difficulty in tongue movement appears.

Media

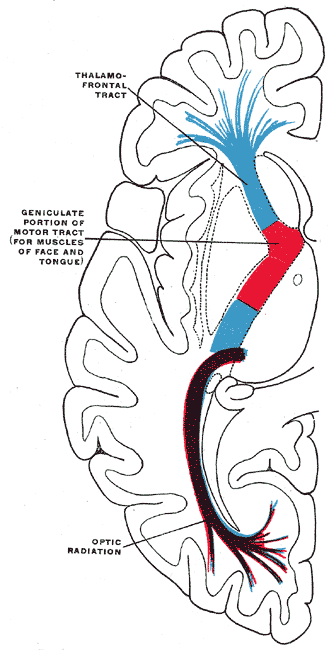

(Click Image to Enlarge)

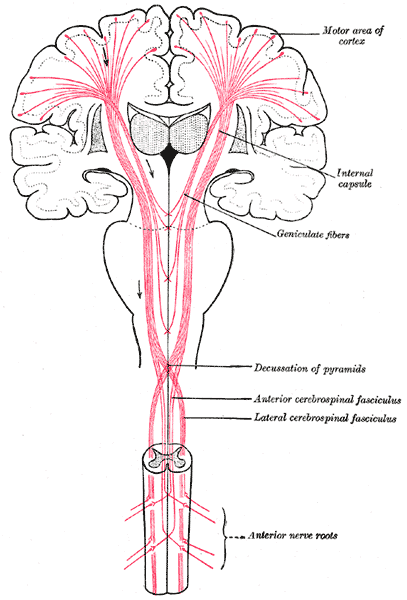

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pathways From the Brain to the Spinal Cord. The figure shows the motor tract, anterior nerve roots, anterior and lateral cerebrospinal fasciculus, decussation of pyramids, geniculate fibers, internal capsule, and motor area of cortex.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Emos MC, Rosner J. Neuroanatomy, Upper Motor Nerve Signs. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082126]

Emos MC, Agarwal S. Neuroanatomy, Upper Motor Neuron Lesion. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725990]

Reid CS, Serrien DJ. Primary motor cortex and ipsilateral control: a TMS study. Neuroscience. 2014 Jun 13:270():20-6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.04.005. Epub 2014 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 24726982]

Meyer BU, Werhahn K, Rothwell JC, Roericht S, Fauth C. Functional organisation of corticonuclear pathways to motoneurones of lower facial muscles in man. Experimental brain research. 1994:101(3):465-72 [PubMed PMID: 7851513]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStiles J, Jernigan TL. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychology review. 2010 Dec:20(4):327-48. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9148-4. Epub 2010 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 21042938]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEmos MC, Khan Suheb MZ, Agarwal S. Neuroanatomy, Internal Capsule. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194338]

Fregosi M, Contestabile A, Badoud S, Borgognon S, Cottet J, Brunet JF, Bloch J, Schwab ME, Rouiller EM. Changes of motor corticobulbar projections following different lesion types affecting the central nervous system in adult macaque monkeys. The European journal of neuroscience. 2018 Aug:48(4):2050-2070. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14074. Epub 2018 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 30019432]

Cavazos JE, Bulsara K, Caress J, Osumi A, Glass JP. Pure motor hemiplegia including the face induced by an infarct of the medullary pyramid. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 1996 Feb:98(1):21-3 [PubMed PMID: 8681473]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSaleem F, Munakomi S. Pseudobulbar Palsy. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31985953]

Nagaoka M, Suzuki H, Kanayama K, Ozone Y. Inability to close mouth and dysphagia caused by pseudobulbar palsy: trial treatment by vibration-induced mastication-like movement. BMJ case reports. 2019 Dec 30:12(12):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-232061. Epub 2019 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 31892622]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence