Introduction

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) is a rare but severe form of childhood epilepsy that was first described by Dr. Henri Gastaut in Marseille, France in 1966.[1]. Dr. William G. Lennox from Boston, United States, described the characteristic electroencephalogram (EEG) features of this condition.[2] The syndrome is aptly named after these two neurologists. LGS is characterized by a triad of multiple seizure types, characteristic EEG findings,[3] and intellectual impairment.[4][5] It is one of the epileptic encephalopathies.[6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) can occur for many reasons; however, approximately 25% of cases have no identified cause. Etiology can be divided into two subtypes:

-

Secondary or Symptomatic LGS: An underlying pathology can be identified with this subtype and is usually from diffuse cerebral injury. Secondary LGS constitutes approximately 75% of cases.[7] Causes include tuberous sclerosis, infections/inflammation such as encephalitis, meningitis, injuries to the frontal lobes of the brain, birth injury/trauma, metabolic causes, and developmental brain malformations. West syndrome, or infantile spasms, is not a specific cause of LGS, but about 30% of children who develop LGS have a prior history of West syndrome[8] and usually have a more severe clinical course.[9]. Secondary LGS tends to have a worse prognosis.

- Idiopathic or Cryptogenic LGS: No underlying pathology can be identified in this subtype, and LGS tends to have a later onset[9]; however, recent genetic studies have found de novo mutations in certain genes, including SCN1A,[10] GABRB3, ALG13, and CHD2.[11][12][13] The significance and actual contribution of these mutations to the development of LGS is unknown at this time.

Epidemiology

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) accounts for approximately 2-5% of all childhood epilepsies,[14][15] but it is responsible for roughly 10% of epilepsy cases occurring before the age of five years.[16][7][15][17][18] The incidence of LGS is estimated at 0.1 to 0.28 per 100,000 population.[7] In children, the incidence is estimated at 2 per 100,000.[7]. The overall prevalence is about 26 per 100,000 people.[7] LGS is more common in males than in females[16]. There are no reports about racial differences. As diffuse brain injury is responsible for a majority of cases, children with developmental and/or intellectual problems are more frequently diagnosed with LGS.

History and Physical

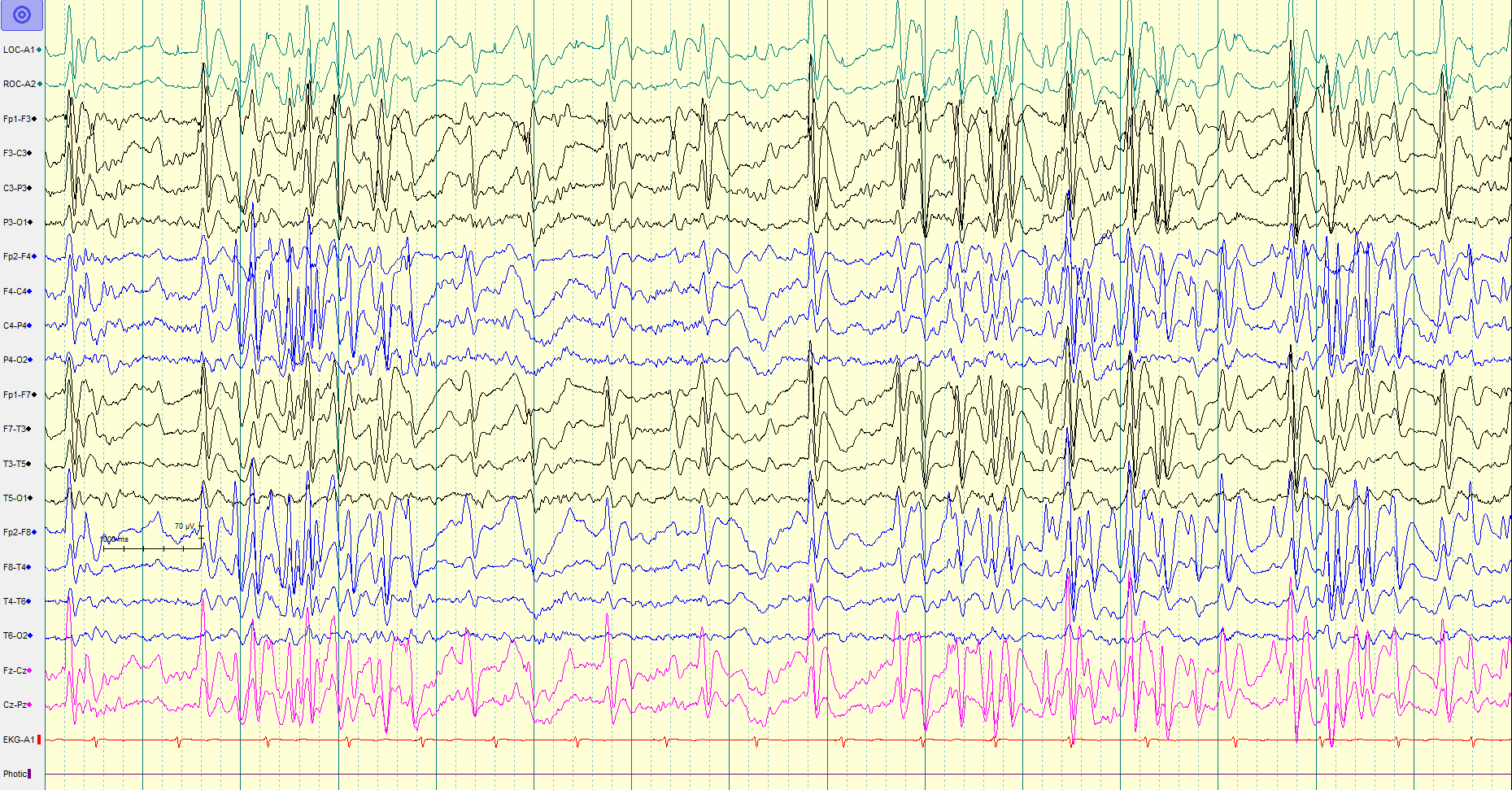

As mentioned, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) is characterized by a triad of multiple seizure types, characteristic electroencephalogram (EEG) findings, and intellectual impairment.[5]

- Seizures: Seizures begin in early childhood, usually between the ages of 1 and 7 years, peaking at around 3 years.[14] Multiple seizure types are seen including tonic, atonic or drop attacks, atypical absence, myoclonic, and generalized tonic-clonic. Tonic seizures are most commonly seen, often occur at night, and are a distinctive feature of LGS.[19] Atypical absence seizures are the second most common subtype seen in LGS. They differ from typical absence seizures in that they have more than just staring episodes associated with eye blinking. Atonic seizures, also known as drop attacks, are seen in over half of the patients and can cause recurrent falls and consequent injuries. Control of atonic seizures is considered an important factor in guiding treatment because of the risks associated with recurrent falls. Approximately half of the patients with LGS go into non-convulsive status epilepticus at some point. It can present with dizziness, staring, apathy, stupor, and unresponsiveness and adds to developmental delay and eventual cognitive issues.[5] It is difficult to identify seizure types in a majority of patients because of the multiple, daily seizure episodes.[5][19] Another confounding factor in the identification of seizures is the emergence of different seizure types over time and a change in frequency. Continuous or video EEG monitoring can be helpful in identifying seizure types in this scenario.[20]

- Characteristic EEG pattern: Please see the "Evaluation" section.

-

Intellectual Impairment: The initial growth in a child with LGS is unremarkable. The decline is seen only after the seizures start and is in the form of developmental delay, intellectual impairment, diminished learning abilities, and behavioral problems. This decline is observed in the majority of the patients and gets worsens with age.[5][19][21] Memory and cognition can still be normal in up to 20% of patients, but these patients will lag in processing information. Patients with LGS show psychomotor regression which means a loss of previously acquired skills. Behavior problems include irritability, hyperactivity, and psychosis.[22] Sometimes, it is difficult to differentiate seizures from behavioral issues. Most patients will eventually have a cognitive disability and static encephalopathy.

Evaluation

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) is diagnosed based on appropriate clinical history (seizure types and intellectual impairment) in the presence of characteristic electroencephalogram (EEG) criteria.[5][19] A standard evaluation with comprehensive birth (prenatal, perinatal, postnatal) history, history of presenting illness/seizures since the onset, history of associated complaints like psychomotor regression, and a full systemic and neurological examination is necessary. Laboratory investigations include hematology and chemistry panel, urinalysis, urine drug screen, serum ammonia, lactic acid, serum amino acids, acylcarnitine profile, and urine organic acids. Imaging studies include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with and without contrast with seizure protocol. An EEG with awake and sleep recording (with activating procedures such as photic stimulation and hyperventilation if possible) is essential. A video EEG may be done to capture and characterize the different seizure types.

Characteristic EEG Pattern: The background activity usually shows generalized slowing with bursts of spike and wave discharges (1.5 to 2.5 Hertz) and paroxysms of fast activity (10 to 20 Hertz).[5][19][23] The spike and wave activity has the highest amplitude over the frontal region, can be periodic or continuous, and can be focal or generalized. Sleep EEG is very important as there are some electrographic features that are activated during sleep and/or seen exclusively during sleep.[5] The spike and wave epileptiform discharges are more frequent and generalized during the non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) EEG as compared to the REM EEG. Tonic seizures are difficult to diagnose, especially in sleep. It is difficult to differentiate the EEG pattern of tonic seizures from infantile spasm.

Diagnosis of idiopathic/cryptogenic LGS can be a challenge initially as the EEG might not be classic, seizures and clinical symptoms evolve over time, and there is no biological marker for the disease. Regular follow up and repeat EEGs are needed to arrive at the final diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) revolves around seizure control and includes medical, dietary, and surgical management. Seizure control is associated with improvement in cognition, mood, alertness, and overall quality of life.

Medical Management: The goal of treatment in LGS is seizure control. Medications help, but only to a certain extent. Seizures are usually refractory, are of different types, and need multiple medications. Control of tonic and atonic seizures are usually given priority because of associated falls and accidents.[24][25] Complications arise frequently because when one medication controls one type of seizures, it can cause or worsen another already existent seizure type. For example, carbamazepine might worsen drop attacks. Thus, knowing seizure types becomes important. Multiple medications have been approved for LGS including felbamate, lamotrigine, rufinamide, valproate, benzodiazepines, topiramate, and recently, cannabidiol oral solution.[26][27][28] [29] Valproate, lamotrigine, and topiramate are considered first-line medications for LGS.[25] A summary of the medications is as follows: (A1)

- Felbamate: Mainly treats atonic and tonic-clinic seizures. Although one of the first medications approved for LGS by the FDA (in 1993); it is also the last one to be used and only if all others fail (has multiple and severe side effects).[30][31][32]

- Lamotrigine: Useful for tonic-clonic seizures and can potentially improve mood and behavior along with speech.[25][26] The FDA approved it in 1998 to be used in combination with other medications for patients > 2 years of age.

- Valproate: Treats multiple seizure types. It is frequently started as the first medication and can be used as monotherapy (since it treats different seizure types) or in combination with other medications.[25]

- Rufinamide: Treats atonic and tonic-clonic seizures.[33] The FDA approved it in 2008 for treatment of LGS in children > 4 years of age or in adults. A distinction of rufinamide is that it does not make other seizure types worse.

- Clobazam: It is a long-acting benzodiazepine and was approved by the FDA in 2011 as an adjunctive for the treatment of seizures in LGS patients > 2 years of age.[29][34]

- Topiramate: Useful in treating tonic-clonic seizures. The FDA approved it as an add-on treatment for seizures in LGS in children >2 years of age.[25][27]

- Cannabidiol (CBD) oral solution: It has been found useful especially for drop attacks but also treats other seizures.[35] It is the latest medication approved by the FDA (in 2018) for children > 2 years of age with LGS.

- Medications like vigabatrin, zonisamide, ethosuximide, clonazepam, levetiracetam have also been used but not well studied in regards to LGS.[25]

- Phenytoin, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, gabapentin, lacosamide, phenobarbital are not used as they can aggravate some seizure types associated with LGS.[36]

- There are reports that corticosteroid[37] and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)[38] therapy may reduce seizure frequency but these reports are not backed by rigorous clinical studies. (A1)

Dietary management: Seizures in LGS are often refractory to medical management. The next step is dietary modifications. These modifications have been studied in children and adults and can decrease seizures and perhaps reduce medication doses. Different diets that have been tested include Ketogenic diet,[39] modified Atkins diet,[40] and low-glycemic-index diet, with some effect.[41](B2)

Surgical management: If medical management and dietary restrictions fail, the next step in the management of LGS is surgical management.[42] Specifically, surgical management is considered when the first two seizure medications fail. This could be in the form of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)[41] or brain surgery.

- Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS): VNS is combined with medical therapy and is most useful for the treatment of drop attacks and tonic-clonic seizures.[43] Interestingly, VNS results usually improve over time, unlike seizure medications. VNS can also be useful for mood and behavior improvement.

- Brain surgery: Surgical options include resection, disconnection (corpus callosotomy), and hemispherectomy. In the past, LGS patients were considered ineligible for surgery, as it was thought to be a generalized epilepsy syndrome. However, patients with secondary LGS can have a resectable lesion (tubers, tumors, malformations) which is the source of seizure activity and can be considered for resection. In LGS, seizures tend to affect both sides of the brain and disconnection by a corpus callosotomy is thought to stop the spread of the seizures from one side to the other. Corpus callosotomy is helpful with atonic, tonic, and tonic-clonic seizures.[44] A limited resection in the form of partial corpus callosotomy is often done as well.[45] (A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Since there is an evolution of symptoms with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS), it is difficult to arrive at a diagnosis right away and requires many years of follow-up.[46] Differential diagnoses include Dravet syndrome, myoclonic-atonic epilepsy (Doose syndrome), atypical benign focal epilepsy of childhood, Pseudo-Lennox-syndrome, and West syndrome.[47]

Prognosis

Overall, the outcome remains poor for patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS). The mortality rate is between 3% and 7% in 8 to 10 years of follow-up. Frequently, death can be from accidents. If there is a history of infantile spasms or West syndrome, the outcome is usually worse with seizure control as well as cognitive status[8][7] while idiopathic LGS patients have less severe symptoms and resultant impairment. SUDEP or Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy may be more common among LGS patients as they generally have uncontrolled seizures[48].

Deterrence and Patient Education

The frequent seizures, resultant intellectual impairment, and complex treatment regimen for a patient (child or adult) with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) require substantial effort by the parents and family. The majority of the time, LGS patients will require 24/7 support in some form. A coordinated approach is needed from a team including a pediatrician, neurologist, psychiatrist, neuropsychologist, and surgeon. Most patients and families will benefit from assessment and help from social and rehabilitation services (physical, occupational, and speech therapy). Efforts need to be made so that patients with LGS receive early intervention whether it be regarding diagnosis, treatment, education, or support services. Families need to be given information about the LGS Foundation and the Epilepsy Foundation of America to optimize outcomes and improve quality of life.

Pearls and Other Issues

Every year, November 1 is observed as International Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (LGS) Awareness Day.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) is a rare but severe form of childhood epilepsy characterized by a triad of multiple seizure types, characteristic EEG findings, and intellectual impairment. It is one of the epileptic encephalopathies. The frequent seizures, resultant intellectual impairment, and complex treatment regimen for a patient (child or adult) with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) require substantial effort by the parents and family. The majority of the time, LGS patients will require 24/7 support in some form. A coordinated interprofessional team approach is needed to improve patient outcomes and quality of life. A team of clinicians including pediatricians, neurologists, psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, and often surgeons is needed to provide a comprehensive treatment plan while minimizing the adverse outcomes.

A team of nurses consisting of pediatric specialty nurses and psychiatric specialty trained nurses is needed to assist the team to augment this treatment plan. The nurses are able to provide parents and patients with the necessary education in regards to the expected course and complications to allow early and prompt treatment of adverse events. The nurses can help individualize patient care by communicating these findings with the clinical providers.

Given the side-effect profile and multitude of medications used to treat LGS the role of the pharmacists becomes vital in the care of LGS. The pharmacist can help directly in treatment planning by providing adequate treatment options and doses of each medication when used in combination with others. The pharmacist is essential in communicating with the providers potential adverse effects of the chosen regimen, as well as inter-drug interactions that may lower the efficacy of antiepileptic agents.

Most patients and families will benefit from assessment and help from social and rehabilitation services (physical, occupational, and speech therapy) to enhance the quality of life for both the patients and their caregivers.

A collaborative interprofessional team approach is needed to ensure that patients with LGS receive early intervention whether it be regarding diagnosis, treatment, education, or support services, to improve patient care and outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gastaut H, Tassinari CA, Roger J, Soulayrol R, Saint Jean M, Regis H, Bernard R, Pinsard N, Dravet C. [Epileptic encephalopathy in children with slow diffuse spike-wares (or petit mal variant) or Lennox syndrome]. Recenti progressi in medicina. 1968 Aug:45(2):117-46 [PubMed PMID: 4984443]

LENNOX WG, DAVIS JP. Clinical correlates of the fast and the slow spike-wave electroencephalogram. Pediatrics. 1950 Apr:5(4):626-44 [PubMed PMID: 15417264]

Markand ON. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (childhood epileptic encephalopathy). Journal of clinical neurophysiology : official publication of the American Electroencephalographic Society. 2003 Nov-Dec:20(6):426-41 [PubMed PMID: 14734932]

Archer JS, Warren AE, Jackson GD, Abbott DF. Conceptualizing lennox-gastaut syndrome as a secondary network epilepsy. Frontiers in neurology. 2014:5():225. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00225. Epub 2014 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 25400619]

Camfield PR. Definition and natural history of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2011 Aug:52 Suppl 5():3-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03177.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21790560]

Khan S, Al Baradie R. Epileptic encephalopathies: an overview. Epilepsy research and treatment. 2012:2012():403592. doi: 10.1155/2012/403592. Epub 2012 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 23213494]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTrevathan E, Murphy CC, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Prevalence and descriptive epidemiology of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome among Atlanta children. Epilepsia. 1997 Dec:38(12):1283-8 [PubMed PMID: 9578523]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOhtahara S, Yamatogi Y, Ohtsuka Y. Prognosis of the Lennox syndrome-long-term clinical and electroencephalographic follow-up study, especially with special reference to relationship with the West syndrome. Folia psychiatrica et neurologica japonica. 1976:30(3):275-87 [PubMed PMID: 992512]

Widdess-Walsh P, Dlugos D, Fahlstrom R, Joshi S, Shellhaas R, Boro A, Sullivan J, Geller E, EPGP Investigators. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome of unknown cause: phenotypic characteristics of patients in the Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project. Epilepsia. 2013 Nov:54(11):1898-904. doi: 10.1111/epi.12395. Epub 2013 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 24116958]

Selmer KK, Lund C, Brandal K, Undlien DE, Brodtkorb E. SCN1A mutation screening in adult patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome features. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2009 Nov:16(3):555-7. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.08.021. Epub 2009 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 19782004]

Epi4K Consortium, Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project, Allen AS, Berkovic SF, Cossette P, Delanty N, Dlugos D, Eichler EE, Epstein MP, Glauser T, Goldstein DB, Han Y, Heinzen EL, Hitomi Y, Howell KB, Johnson MR, Kuzniecky R, Lowenstein DH, Lu YF, Madou MR, Marson AG, Mefford HC, Esmaeeli Nieh S, O'Brien TJ, Ottman R, Petrovski S, Poduri A, Ruzzo EK, Scheffer IE, Sherr EH, Yuskaitis CJ, Abou-Khalil B, Alldredge BK, Bautista JF, Berkovic SF, Boro A, Cascino GD, Consalvo D, Crumrine P, Devinsky O, Dlugos D, Epstein MP, Fiol M, Fountain NB, French J, Friedman D, Geller EB, Glauser T, Glynn S, Haut SR, Hayward J, Helmers SL, Joshi S, Kanner A, Kirsch HE, Knowlton RC, Kossoff EH, Kuperman R, Kuzniecky R, Lowenstein DH, McGuire SM, Motika PV, Novotny EJ, Ottman R, Paolicchi JM, Parent JM, Park K, Poduri A, Scheffer IE, Shellhaas RA, Sherr EH, Shih JJ, Singh R, Sirven J, Smith MC, Sullivan J, Lin Thio L, Venkat A, Vining EP, Von Allmen GK, Weisenberg JL, Widdess-Walsh P, Winawer MR. De novo mutations in epileptic encephalopathies. Nature. 2013 Sep 12:501(7466):217-21. doi: 10.1038/nature12439. Epub 2013 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 23934111]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLund C, Brodtkorb E, Øye AM, Røsby O, Selmer KK. CHD2 mutations in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2014 Apr:33():18-21. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.02.005. Epub 2014 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 24614520]

Capelli LP, Krepischi AC, Gurgel-Giannetti J, Mendes MF, Rodrigues T, Varela MC, Koiffmann CP, Rosenberg C. Deletion of the RMGA and CHD2 genes in a child with epilepsy and mental deficiency. European journal of medical genetics. 2012 Feb:55(2):132-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2011.10.004. Epub 2011 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 22178256]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBourgeois BF, Douglass LM, Sankar R. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: a consensus approach to differential diagnosis. Epilepsia. 2014 Sep:55 Suppl 4():4-9. doi: 10.1111/epi.12567. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25284032]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHeiskala H. Community-based study of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 1997 May:38(5):526-31 [PubMed PMID: 9184597]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAsadi-Pooya AA, Sharifzade M. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in south Iran: electro-clinical manifestations. Seizure. 2012 Dec:21(10):760-3. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.08.003. Epub 2012 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 22921514]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCrumrine PK. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Journal of child neurology. 2002 Jan:17 Suppl 1():S70-5 [PubMed PMID: 11918467]

Goldsmith IL, Zupanc ML, Buchhalter JR. Long-term seizure outcome in 74 patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: effects of incorporating MRI head imaging in defining the cryptogenic subgroup. Epilepsia. 2000 Apr:41(4):395-9 [PubMed PMID: 10756403]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceArzimanoglou A, French J, Blume WT, Cross JH, Ernst JP, Feucht M, Genton P, Guerrini R, Kluger G, Pellock JM, Perucca E, Wheless JW. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: a consensus approach on diagnosis, assessment, management, and trial methodology. The Lancet. Neurology. 2009 Jan:8(1):82-93. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70292-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19081517]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBare MA, Glauser TA, Strawsburg RH. Need for electroencephalogram video confirmation of atypical absence seizures in children with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Journal of child neurology. 1998 Oct:13(10):498-500 [PubMed PMID: 9796756]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOguni H, Hayashi K, Osawa M. Long-term prognosis of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 1996:37 Suppl 3():44-7 [PubMed PMID: 8681912]

Glauser TA. Following catastrophic epilepsy patients from childhood to adulthood. Epilepsia. 2004:45 Suppl 5():23-6 [PubMed PMID: 15283708]

Asadi-Pooya AA, Dlugos D, Skidmore C, Sperling MR. Atlas of Electroencephalography, 3rd Edition. Epileptic disorders : international epilepsy journal with videotape. 2017 Sep 1:19(3):384. doi: 10.1684/epd.2017.0934. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28872032]

Shyu HY, Lin JH, Chen C, Kwan SY, Yiu CH. An atypical case of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome not associated with mental retardation: a nosological issue. Seizure. 2011 Dec:20(10):820-3. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2011.08.001. Epub 2011 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 21862354]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMichoulas A, Farrell K. Medical management of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. CNS drugs. 2010 May:24(5):363-74. doi: 10.2165/11530220-000000000-00000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20158289]

Motte J, Trevathan E, Arvidsson JF, Barrera MN, Mullens EL, Manasco P. Lamotrigine for generalized seizures associated with the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Lamictal Lennox-Gastaut Study Group. The New England journal of medicine. 1997 Dec 18:337(25):1807-12 [PubMed PMID: 9400037]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSachdeo RC, Glauser TA, Ritter F, Reife R, Lim P, Pledger G. A double-blind, randomized trial of topiramate in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Topiramate YL Study Group. Neurology. 1999 Jun 10:52(9):1882-7 [PubMed PMID: 10371538]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGlauser T, Kluger G, Sachdeo R, Krauss G, Perdomo C, Arroyo S. Rufinamide for generalized seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Neurology. 2008 May 20:70(21):1950-8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303813.95800.0d. Epub 2008 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 18401024]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNg YT, Conry J, Mitchell WG, Buchhalter J, Isojarvi J, Lee D, Drummond R, Chung S. Clobazam is equally safe and efficacious for seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome across different age groups: Post hoc analyses of short- and long-term clinical trial results. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2015 May:46():221-6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.01.037. Epub 2015 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 25940107]

Felbamate Study Group in Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. Efficacy of felbamate in childhood epileptic encephalopathy (Lennox-Gastaut syndrome). The New England journal of medicine. 1993 Jan 7:328(1):29-33 [PubMed PMID: 8347179]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDevinsky O, Faught RE, Wilder BJ, Kanner AM, Kamin M, Kramer LD, Rosenberg A. Efficacy of felbamate monotherapy in patients undergoing presurgical evaluation of partial seizures. Epilepsy research. 1995 Mar:20(3):241-6 [PubMed PMID: 7796796]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceO'Neil MG, Perdun CS, Wilson MB, McGown ST, Patel S. Felbamate-associated fatal acute hepatic necrosis. Neurology. 1996 May:46(5):1457-9 [PubMed PMID: 8628501]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJaraba S, Santamarina E, Miró J, Toledo M, Molins A, Burcet J, Becerra JL, Raspall M, Pico G, Miravet E, Cano A, Fossas P, Fernández S, Falip M. Rufinamide in children and adults in routine clinical practice. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 2017 Jan:135(1):122-128. doi: 10.1111/ane.12572. Epub 2016 Feb 29 [PubMed PMID: 26923380]

Wheless JW, Isojarvi J, Lee D, Drummond R, Benbadis SR. Clobazam is efficacious for patients across the spectrum of disease severity of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: post hoc analyses of clinical trial results by baseline seizure-frequency quartiles and VNS experience. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2014 Dec:41():47-52. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.09.019. Epub 2014 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 25282105]

Devinsky O, Marsh E, Friedman D, Thiele E, Laux L, Sullivan J, Miller I, Flamini R, Wilfong A, Filloux F, Wong M, Tilton N, Bruno P, Bluvstein J, Hedlund J, Kamens R, Maclean J, Nangia S, Singhal NS, Wilson CA, Patel A, Cilio MR. Cannabidiol in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy: an open-label interventional trial. The Lancet. Neurology. 2016 Mar:15(3):270-8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00379-8. Epub 2015 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 26724101]

Asadi-Pooya AA, Emami M, Ashjazadeh N, Nikseresht A, Shariat A, Petramfar P, Yousefipour G, Borhani-Haghighi A, Izadi S, Rahimi-Jaberi A. Reasons for uncontrolled seizures in adults; the impact of pseudointractability. Seizure. 2013 May:22(4):271-4. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2013.01.010. Epub 2013 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 23375939]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePera MC, Randazzo G, Masnada S, Dontin SD, De Giorgis V, Balottin U, Veggiotti P. Intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy for children with epileptic encephalopathy. Functional neurology. 2015 Jul-Sep:30(3):173-9 [PubMed PMID: 26910177]

Mikati MA, Kurdi R, El-Khoury Z, Rahi A, Raad W. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in intractable childhood epilepsy: open-label study and review of the literature. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2010 Jan:17(1):90-4. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.10.020. Epub 2009 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 20004620]

Caraballo RH, Fortini S, Fresler S, Armeno M, Ariela A, Cresta A, Mestre G, Escobal N. Ketogenic diet in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Seizure. 2014 Oct:23(9):751-5. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.06.005. Epub 2014 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 25011392]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSharma S, Jain P, Gulati S, Sankhyan N, Agarwala A. Use of the modified Atkins diet in Lennox Gastaut syndrome. Journal of child neurology. 2015 Apr:30(5):576-9. doi: 10.1177/0883073814527162. Epub 2014 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 24659735]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKim SH, Kang HC, Lee EJ, Lee JS, Kim HD. Low glycemic index treatment in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Brain & development. 2017 Sep:39(8):687-692. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2017.03.027. Epub 2017 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 28431772]

Douglass LM, Salpekar J. Surgical options for patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2014 Sep:55 Suppl 4():21-8. doi: 10.1111/epi.12742. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25284034]

Lancman G, Virk M, Shao H, Mazumdar M, Greenfield JP, Weinstein S, Schwartz TH. Vagus nerve stimulation vs. corpus callosotomy in the treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: a meta-analysis. Seizure. 2013 Jan:22(1):3-8. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.09.014. Epub 2012 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 23068970]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAsadi-Pooya AA, Malekmohamadi Z, Kamgarpour A, Rakei SM, Taghipour M, Ashjazadeh N, Inaloo S, Razmkon A, Zare Z. Corpus callosotomy is a valuable therapeutic option for patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and medically refractory seizures. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2013 Nov:29(2):285-8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.08.011. Epub 2013 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 24012506]

Asadi-Pooya AA, Sharan A, Nei M, Sperling MR. Corpus callosotomy. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2008 Aug:13(2):271-8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.04.020. Epub 2008 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 18539083]

Kerr M, Kluger G, Philip S. Evolution and management of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome through adolescence and into adulthood: are seizures always the primary issue? Epileptic disorders : international epilepsy journal with videotape. 2011 May:13 Suppl 1():S15-26. doi: 10.1684/epd.2011.0409. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21669559]

Wirrell E, Farrell K, Whiting S. The epileptic encephalopathies of infancy and childhood. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 2005 Nov:32(4):409-18 [PubMed PMID: 16408569]

Berg AT, Nickels K, Wirrell EC, Geerts AT, Callenbach PM, Arts WF, Rios C, Camfield PR, Camfield CS. Mortality risks in new-onset childhood epilepsy. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul:132(1):124-31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3998. Epub 2013 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 23753097]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence