Introduction

Aortic dissection, though uncommon, is a catastrophic vascular disorder characterized by a tear in the intimal layer of the aorta, leading to the separation of the aortic wall layers. Blood enters between the intima and media, propagating the dissection either proximally or retrograde, resulting in compromised blood flow to vital organs. Acute aortic dissection carries extremely high mortality rates, with many patients dying before reaching emergency care. Patients with chronic aortic dissection, defined as a dissection present for more than 2 weeks, have a slightly better prognosis.

While the classic presentation of acute aortic dissection involves sudden, severe, “tearing” chest pain, subtle presentations often lead to missed diagnoses. Despite the literature, many aortic dissections are missed in the emergency department; only 15% to 43% of verified cases are accurately diagnosed at first presentation.[1][2][3] Without treatment, mortality approaches 50% within 48 hours of symptom onset. Despite its rarity, acute aortic dissection requires prompt diagnosis and multidisciplinary healthcare intervention, with better outcomes observed in high-volume centers utilizing experienced teams, “aorta code” protocols, and specialized aortic centers.[4] Further, implementing a multidisciplinary strategy with vascular surgery and cardiology expertise is essential to improving patient outcomes in these life-threatening cases. Aortic dissections are classified anatomically by 2 systems: the Stanford and DeBakey classification systems.

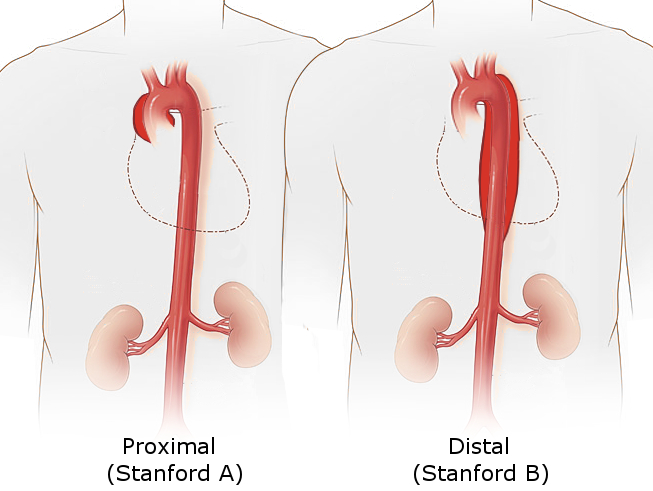

The Stanford system categorizes dissections into 2 types based on whether the ascending or descending part of the aorta is involved (see Image. Stanford Classification of Aortic Dissection).

- Stanford Type A: This involves the ascending aorta, regardless of the site of the primary intimal tear (see Image. Type A Aortic Dissection), and is defined as a dissection proximal to the brachiocephalic artery.

- Stanford Type B: This originates distal to the left subclavian artery and involves only the descending aorta; the Society for Vascular Surgery and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons define Stanford type B dissections as those where the entry tear occurs beyond the origin of the innominate artery.[5]

The DeBakey system further subdivides dissections into 3 types based on the origin and extent of the dissection:

- DeBakey Type 1: Originates in the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and descending aorta

- DeBakey Type 2: Originates in and is limited to the ascending aorta

- DeBakey Type 3: Begins in the descending aorta and extends distally above the diaphragm (type 3a) or below the diaphragm (type 3b)

Ascending dissections (Stanford type A or DeBakey types 1 and 2) are nearly twice as common as descending dissections (Stanford type B or DeBakey type 3), necessitating an urgent, specialized approach to reduce the risk of fatal complications such as aortic rupture, stroke, or myocardial infarction (see Image. Aortic Dissection, Type A).[6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Predisposing high-risk factors for nontraumatic aortic dissection include:

- Hypertension (occurs in 70% of patients with distal Stanford type B dissections)

- An abrupt, transient, severe increase in blood pressure (eg, strenuous weight lifting and use of sympathomimetic agents such as cocaine, ecstasy, or energy drinks)

- Genetic conditions include:

- Marfan syndrome

- In an International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) review, Marfan syndrome was present in 50% of those younger than 40, compared with only 2% of older patients.

- In patients with Marfan syndrome, cystic medial necrosis is seen in the tissues.

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Turner syndrome

- Bicuspid aortic valve

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Marfan syndrome

- Preexisting aortic aneurysm

- Atherosclerosis

- Pregnancy and delivery

- This risk is compounded in pregnant women with connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome.

- Family history

- Aortic instrumentation or surgery (eg, coronary artery bypass, aortic or mitral valve replacement, and percutaneous stenting or catheter insertion)

- Inflammatory or infectious diseases that cause vasculitis (eg, syphilis, cocaine use) [7]

Epidemiology

Acute aortic dissection is a rare but life-threatening condition, with an incidence of 5 to 30 cases per 1 million people per year. This contrasts sharply with acute myocardial infarction, which has approximately 4400 cases per 1 million people annually. Aortic dissection accounts for 3 out of every 1000 emergency department presentations involving acute chest, back, or abdominal pain. The condition predominantly affects individuals between 40 and 70, with most cases occurring in patients aged 50 to 65. Approximately 75% of dissections happen in this age range, highlighting age as a key risk factor.

While men are 3 times more likely to develop aortic dissection than women, women often present later in the disease course and have worse outcomes.[8] The risk profile differs between older and younger patients: older patients are more likely to have hypertension, atherosclerosis, prior aortic aneurysm, or iatrogenic dissection, while younger patients, particularly those younger than 40, are more likely to have connective tissue disorders like Marfan syndrome. Type A dissections involving the ascending aorta are twice as common as type B dissections and are more likely to be fatal without urgent intervention. Hypertension is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor, present in about 75% of patients, while other risk factors include atherosclerosis, connective tissue disorders, and previous cardiac surgery.

Pathophysiology

Aortic dissection occurs when a tear in the intimal layer of the aortic wall allows blood to enter the space between the intima and media, creating a false lumen. The aortic wall has 3 layers: the intima, media, and adventitia. Chronic exposure to high pulsatile pressure and shear stress, especially in susceptible individuals, weakens these layers, leading to the initial intimal tear. This tear typically occurs in the ascending aorta, particularly in the right lateral wall, where shear forces are highest. The blood then flows into the space between the intima and media, expanding the false lumen.

In most cases, the dissection propagates either anterograde (distally) or retrograde (proximally). The direction of propagation dictates the complications that arise: distal propagation can obstruct blood flow to the major branches of the aorta, leading to ischemia in affected territories such as the coronary, cerebral, spinal, or visceral arteries. Proximal propagation, as seen in type A dissections, often causes life-threatening complications like acute aortic regurgitation, cardiac tamponade, or even rupture.[9] As the false lumen develops, it typically becomes larger than the true lumen, increasing the risk of aneurysm formation and eventual rupture if left untreated. The 3 most common sites for acute aortic dissection include:

- The area approximately 2 to 2.5 cm above the aortic root (the most frequent site)

- Just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery

- Within the aortic arch

These dissections are highly lethal if not recognized and treated promptly, often leading to death due to aortic rupture or tamponade.

Histopathology

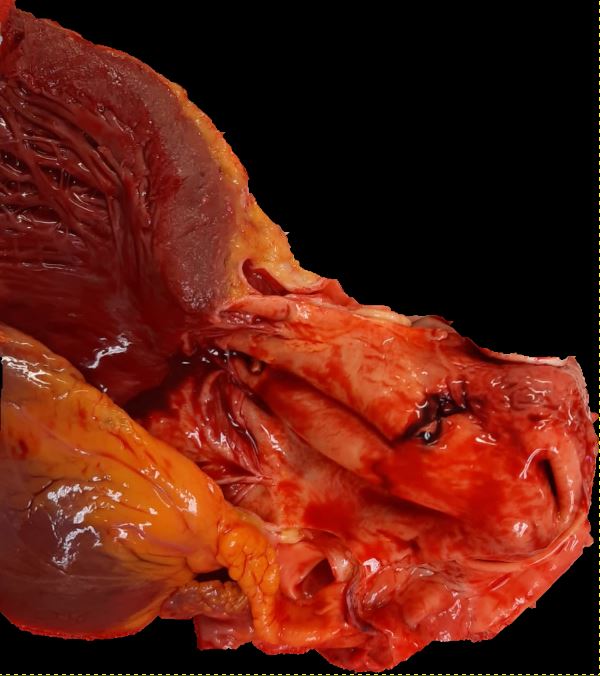

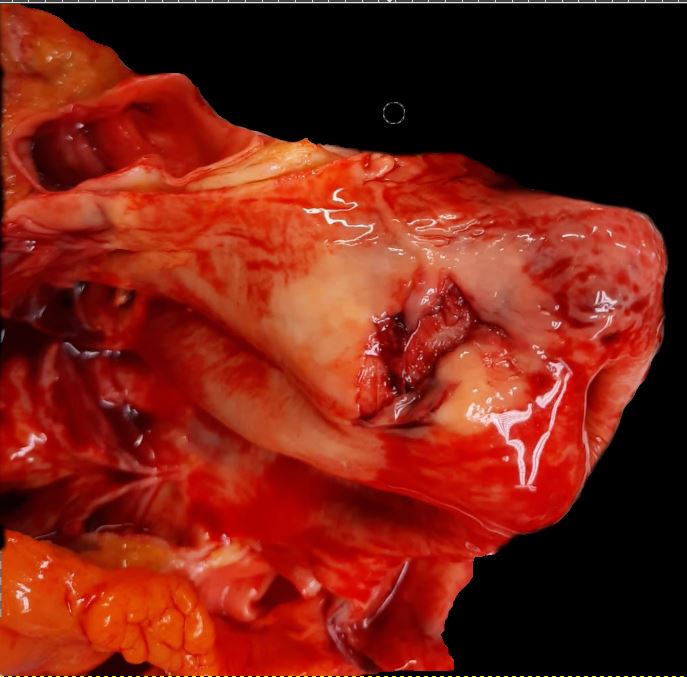

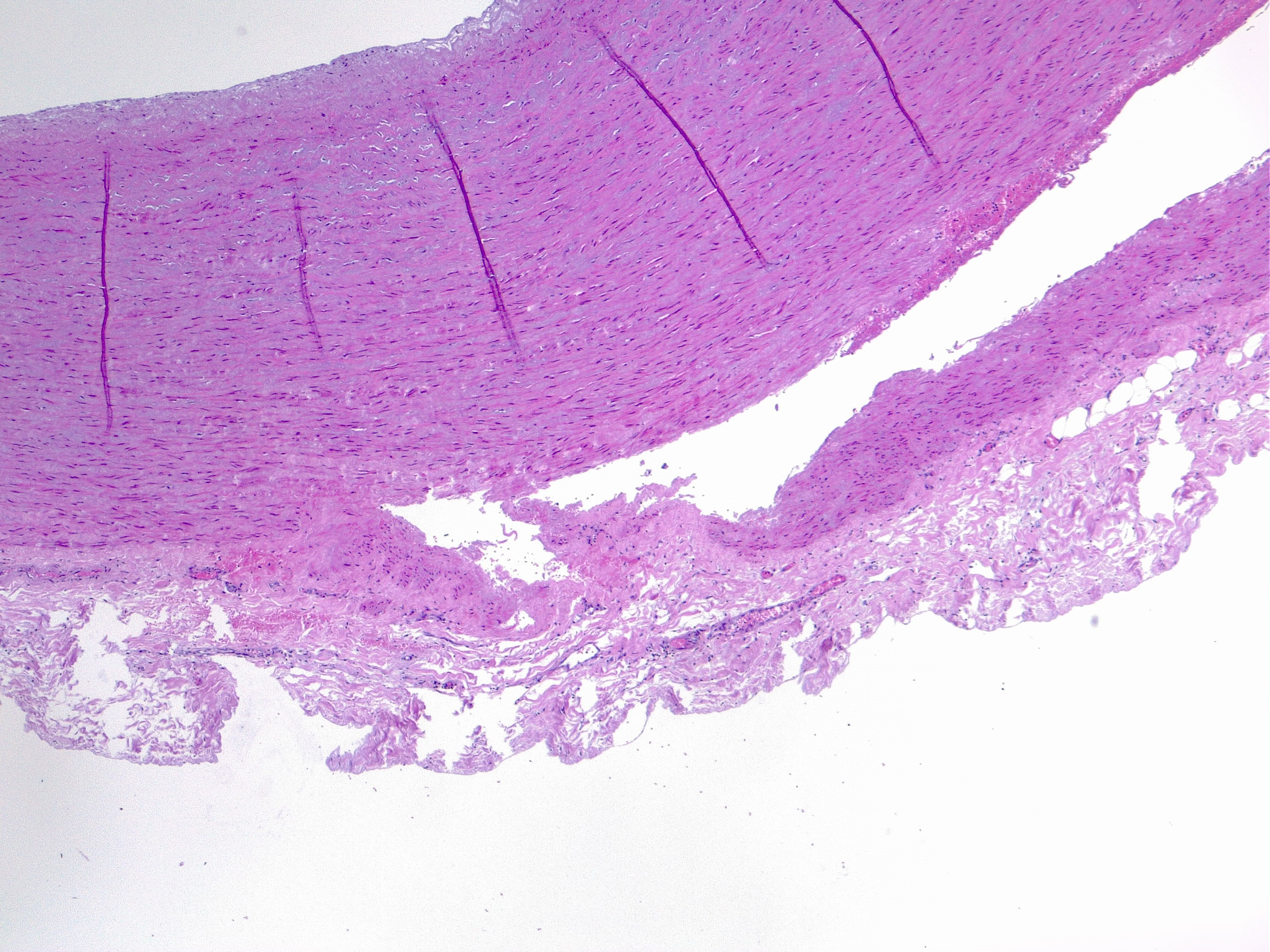

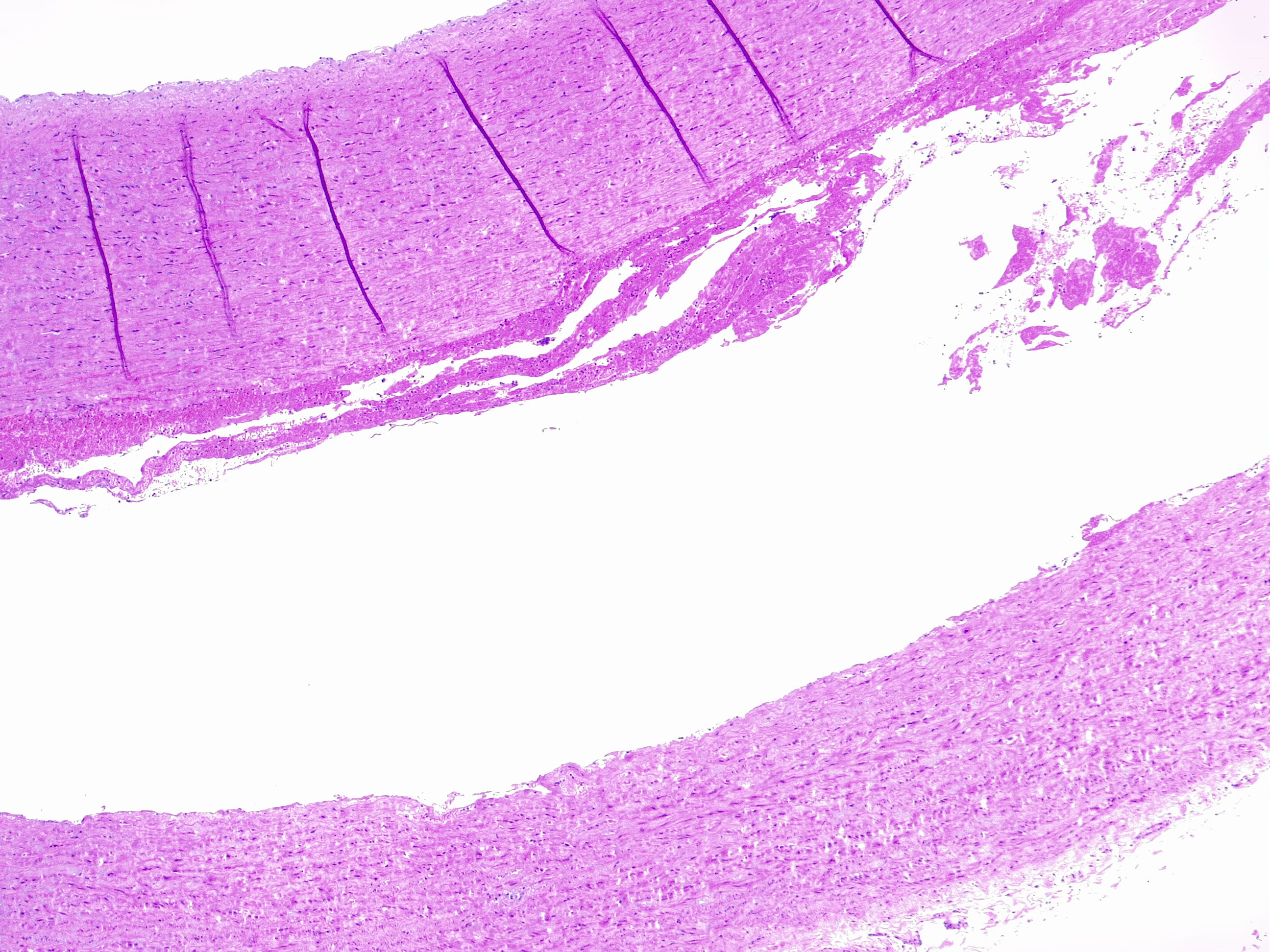

Aortic dissection is an acute life-threatening condition that occurs when a tear in the intimal layer of the aorta allows blood to flow between the layers of the aortic wall, creating a false lumen between the intima-media and media-adventitia layers (see Image. Aortic Dissection Seen in Histology). This process can lead to a sudden drop in systemic blood pressure and cause catastrophic complications such as hemopericardium and cardiac tamponade, which can result in sudden death.[10] The dissection commonly occurs in the outer one-third of the aortic media, a structurally vulnerable area due to chronic injury and repair processes often triggered by hemodynamic forces like hypertension (see Image. Histologic Image of Aortic Dissection).[11] The dissection can progress in anterograde or retrograde directions, potentially obstructing branches of the aorta and leading to ischemia in organs such as the brain, heart, or kidneys.

The media layer of the aorta, composed of smooth muscle cells, elastic fibers, collagen fibers, and extracellular matrix components such as hyaluronic acid, undergoes pathological changes in the setting of chronic hypertension or genetic predisposition. These changes, collectively termed cystic medial degeneration, include:

- Mucoid accumulation

- This occurs in the extracellular matrix and increases the interlamellar or translamellar space, creating the so-called “cystic degeneration” of the media that decreases vessel resistance. The main component of mucin accumulation is chondroitin-6-sulfate.[12]

- Alteration of elastic fibers

- Under normal conditions, a dense meshwork of elastic fibers in the media maintains the aorta's structural integrity. These fibers provide elasticity and resistance to the constant pulsatile forces exerted by blood pressure. Alterations in these elastic fibers, such as fragmentation, thinning, and disorganization, compromise the aorta's ability to withstand these forces.

- Fragmentation of elastic fibers increases the spaces between the lamellar layers (translamellar spaces), weakening the aorta's mechanical strength and elasticity. This renders the vessel more prone to dissection, as the weakened wall can't resist the high shear forces of blood flow very well.

- Thinning these fibers further weakens the vessel wall, widening the spaces between elastic fibers and reducing the aorta's overall resilience. This makes the aorta susceptible to dilation, aneurysm formation, and dissection.

- Disorganization refers to the loss of the parallel arrangement of elastic fibers, which are normally aligned in an orderly fashion to withstand pressure. When disorganized, the fibers are haphazardly arranged and unable to function effectively, leading to a loss of structural cohesion and increasing the risk of tears within the aortic wall.

- Under normal conditions, a dense meshwork of elastic fibers in the media maintains the aorta's structural integrity. These fibers provide elasticity and resistance to the constant pulsatile forces exerted by blood pressure. Alterations in these elastic fibers, such as fragmentation, thinning, and disorganization, compromise the aorta's ability to withstand these forces.

- Altered smooth muscle cells

- Smooth muscle cells undergo nuclear loss and disorganization.

- Nuclear cell loss, so-called “smooth muscle cell necrosis,” can appear in bands or as wide areas where only the ghost cell contours are visible. The disarray of smooth muscle cells can be focal or nodular.

- Smooth muscle cells undergo nuclear loss and disorganization.

- Laminar medial collapse

- The collapsing of elastic fibers represents “laminar medial necrosis” and is coupled with significant loss of interposed smooth muscle cells.

- Collagen fibrosis

- Collagen fibers can become fibrotic; this is the least common process in degenerative aortic disease.

These findings are often combined and must be carefully recognized to accurately grade the degree of medial degeneration as mild, moderate, or severe. This grading is determined by evaluating the severity and distribution of the degenerative lesions observed within the aortic wall.[13][14] Each category reflects the extent of structural damage, including alterations in elastic fibers, smooth muscle cell integrity, and the extracellular matrix. Identifying these changes is crucial for understanding the underlying pathology and predicting potential outcomes, as more severe degeneration is associated with a higher risk of complications such as aortic dissection or rupture. Histopathological evaluation using stains like Verhoeff-Van Gieson, Alcian blue, and Masson trichrome can reveal the extent of these alterations.

The vasa vasorum, a network of small vessels supplying the outer layers of the aortic wall, plays a critical role in maintaining the integrity of the media. Dysfunction of the vasa vasorum, such as obstruction or thickening, can lead to medial necrosis and contribute to the development of aortic dissection. Hypertension is the most important risk factor for medial degeneration and aortic dissection, causing intimal thickening, aortic stiffness, and damage to the elastic fibers.[15][16] Aging exacerbates these degenerative processes, with a loss of elastin, increased collagen deposition, and microcalcifications in the media, further increasing the risk in older populations.[17] This is the primary physiological reason for the high epidemiological correlation between age and aortic diseases such as aneurysms and dissection.[12] Genetic factors also contribute to aortic dissection risk. Conditions such as Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Loeys-Dietz syndrome result in altered elastic fiber meshwork, predisposing individuals to aneurysms and dissections. Additionally, congenital cardiovascular diseases like a bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation of the aorta, and tetralogy of Fallot are associated with structural abnormalities of the aortic wall, further increasing the risk of dissection in affected individuals.

History and Physical

Acute aortic dissection presents with a range of symptoms that reflect the extent of the dissection and the specific cardiovascular structures involved. The patient’s history plays a crucial role in recognizing the dissection, and 3 key elements should be emphasized: the quality, radiation, and intensity of pain at the onset. Study results have identified pain intensity at onset as one of the most reliable historical factors in diagnosing acute aortic dissection. The classic presentation is a sudden, severe, tearing pain that often reaches maximum intensity within minutes. The location of the pain may vary, typically appearing in the anterior chest for dissections involving the ascending aorta and in the back for those involving the descending aorta. Additionally, the pain may migrate as the dissection extends distally. In about 10% of cases, especially in individuals with Marfan syndrome, patients may not report pain, complicating the clinical picture.

While the hallmark presentation of acute aortic dissection includes severe chest or back pain, it can be accompanied by neurological symptoms or limb ischemia, depending on the vessels involved. The presence of chest pain with neurological deficits (such as stroke-like symptoms, limb weakness, or paresthesia), the combination of chest and abdominal pain, or chest pain with syncope should all prompt suspicion of acute aortic dissection.[18] Neurological deficits are seen in approximately 20% of patients, and syncope is relatively common, which can be due to various mechanisms, including hypovolemia, arrhythmias, or myocardial infarction. If the dissection propagates into peripheral vessels, symptoms like loss of pulses, pain, and paresthesias in the extremities may occur. Physical findings are diverse and may provide critical diagnostic clues. Still, classical signs like blood pressure discrepancies between the upper extremities, pulse deficits, or a diastolic murmur are found in less than 50% of confirmed acute aortic dissection cases. These signs should raise clinical suspicion, especially if combined with typical pain and neurological symptoms. Blood pressure discrepancies greater than 20 mm Hg between arms, a pulse deficit, or wide pulse pressure are red flags in the physical exam.

Hypertension is common in acute aortic dissection, but hypotension is a grave sign, often indicating aortic rupture or cardiac tamponade. Patients may present with muffled heart sounds, syncope, and shock in such cases. A new diastolic murmur suggests aortic insufficiency, often associated with proximal dissections. If the dissection involves the carotid or subclavian arteries, signs of Horner syndrome (ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis) or hoarseness due to recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement may appear. Additionally, dyspnea and hemoptysis may result from dissection rupture into the mediastinum. Notably, if a patient presents with abdominal pain, renal or biliary colic, or bowel obstruction/perforation, nondissection-related mesenteric ischemia should be considered. Pulse deficit can be a sign of nondissection-related embolic phenomena or arterial occlusion.[19] In summary, the clinical presentation of acute aortic dissection varies widely. While the classic signs and symptoms are invaluable for diagnosis, the absence of these features does not rule out the condition. A combination of a detailed pain history, neurological findings, and physical examination features such as blood pressure discrepancies, pulse deficits, or murmurs should alert clinicians to the possibility of a dissection and prompt immediate diagnostic evaluation.

Evaluation

The evaluation and workup of acute aortic dissection are centered on rapid identification and confirmation of the condition, given its high mortality if left untreated. The diagnostic approach is guided by clinical suspicion, the patient’s hemodynamic stability, and the availability of imaging modalities. An integrated approach combining clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and advanced imaging modalities is essential to confirm the diagnosis and determine the appropriate management.

Clinical Evaluation

As previously discussed, the initial assessment begins with a focused history and physical examination. Once a patient with a possible aortic dissection is identified, further workup begins.

Electrocardiogram

Although an electrocardiogram (ECG) is routinely performed to evaluate chest pain, its findings are often nonspecific in an acute aortic dissection. ST-segment changes may suggest myocardial ischemia, particularly if the dissection extends to involve the coronary arteries. The presence of ECG findings consistent with an acute myocardial infarction occurs in 8% of cases of acute aortic dissection. However, a normal ECG does not exclude a dissection, and a high index of clinical suspicion should be maintained based on presenting symptoms and history.

Chest Radiography

A chest x-ray may reveal a widened mediastinum (>8 cm), abnormal aortic contour, pleural effusion, or loss of the aortic knob, suggesting aortic dissection. However, up to 20% of patients may have a normal chest x-ray, so the absence of findings does not rule out the diagnosis. Additional suggestive findings include:

- Left apical cap

- Pleural effusion

- Deviation of the esophagus or trachea

- Depression of the left mainstem bronchus

- Loss of the paratracheal stripe

Laboratory Evaluation

Laboratory tests are useful adjuncts but are not diagnostic for acute aortic dissection. They help assess the clinical status and organ function. Important laboratory tests include:

- D-dimer: Elevated D-dimer levels (>500 ng/mL) are highly sensitive to acute aortic dissection due to increased fibrinolytic activity from forming a false lumen. However, D-dimer lacks specificity and should not be used as a standalone test, but it may help rule out the condition in low-risk patients.

- Cardiac biomarkers, including troponin: Mildly elevated troponin levels may be seen, especially if there is coronary artery involvement or myocardial infarction.

- Complete blood count: Leukocytosis is common but nonspecific. A drop in hematocrit may suggest intraluminal blood loss.

- Renal function tests: Elevated creatinine levels can indicate renal ischemia from dissection involving the renal arteries.

- Serum lactate levels: Elevated lactate levels may indicate poor perfusion or tissue ischemia due to branch vessel involvement.

- Smooth muscle myosin heavy chain assay: An elevated smooth muscle myosin heavy chain SM-MHC assay is specific for acute aortic dissection. The SM-MHC assay is a rapid 30-minute test that can detect circulating SM-MHC protein. However, smooth muscle proteins can only detect the dissection after it occurs, and they are not useful for predicting or monitoring chronic aortic dissections.

Imaging Modalities

Definitive diagnosis of aortic dissection relies on advanced imaging to identify the intimal tear, evaluate the extent of dissection, and assess complications. The choice of imaging modality is determined by the patient’s stability, clinical scenario, and institutional availability:

- Computed tomography angiography

- Computed tomography (CTA) is the first-line imaging modality in most cases due to its high sensitivity and specificity, widespread availability, and rapid acquisition.[20] This modality provides detailed images of the aorta, showing the intimal flap, true and false lumens, aortic dilation, hematoma, and complications such as contrast leak (indicating rupture) and branch vessel involvement. CTA is particularly useful in differentiating type A and type B dissections.

- Transesophageal echocardiography

- Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is often the imaging modality of choice in hemodynamically unstable patients or when CTA is not available. TEE provides high-resolution, real-time images of the aortic root, ascending aorta, and descending thoracic aorta, enabling accurate detection of proximal dissections (type A) and complications like aortic regurgitation or cardiac tamponade. TEE is also valuable during intraoperative evaluations, guiding surgical or endovascular procedures, and assessing blood flow in the true and false lumens before and immediately after aortic interventions.[7] Findings may include:

- Dissection flap with differential Doppler flow

- True and false lumen in the ascending aorta

- Thrombosis in the false lumen

- Central displacement of intimal calcification

- Pericardial effusion

- Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is often the imaging modality of choice in hemodynamically unstable patients or when CTA is not available. TEE provides high-resolution, real-time images of the aortic root, ascending aorta, and descending thoracic aorta, enabling accurate detection of proximal dissections (type A) and complications like aortic regurgitation or cardiac tamponade. TEE is also valuable during intraoperative evaluations, guiding surgical or endovascular procedures, and assessing blood flow in the true and false lumens before and immediately after aortic interventions.[7] Findings may include:

- Magnetic resonance imaging

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is highly accurate but less commonly used in acute settings due to limited availability and longer acquisition times. This modality is particularly useful for follow-up in chronic dissections and patients with contraindications to iodinated contrast. MRI offers excellent visualization of branch vessel involvement and soft tissue contrast, making it preferred in selected cases.

- Transthoracic echocardiography

- Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is less reliable for diagnosing aortic dissections due to poor visualization of the distal aorta but is beneficial for evaluating patients with acute aortic syndromes and assessing complications such as aortic regurgitation, left ventricular dysfunction, and pericardial effusion (suggesting tamponade).[7] TTE can be used as an initial bedside tool in unstable patients.

- Aortography

- Once the gold standard for evaluating aortic dissections, aortography is now rarely used for initial diagnosis but may still be employed when planning endovascular stent placement.

Risk Stratification Tools

Clinical decision-making tools such as the Aortic Dissection Detection Risk Score (ADD-RS) can help identify high-risk AAD patients. This scoring system incorporates factors from history, physical examination, and imaging to guide the need for further testing. A high-risk ADD-RS score, combined with elevated D-dimer, increases the likelihood of AAD and may justify immediate imaging. Prompt recognition and diagnosis of AAD are crucial to prevent catastrophic complications, including aortic rupture, cardiac tamponade, or ischemic injury to vital organs. Timely imaging, particularly CTA, remains central to confirming the diagnosis and guiding management decisions.

Treatment / Management

Management of aortic dissection begins with immediate stabilization and consultation with a cardiothoracic or vascular surgeon, regardless of the location of the dissection. Due to the high mortality associated with untreated AAD, the approach to management involves a combination of urgent surgical intervention and medical therapy to reduce hemodynamic stress on the aorta.

Initial Stabilization and Medical Management

Once the diagnosis of acute aortic dissection is confirmed or highly suspected, a multidisciplinary team should be activated promptly. Initial management includes:

- Monitoring and access

- Continuous monitoring with an arterial line for real-time blood pressure measurements

- Placement of a central venous catheter for hemodynamic monitoring and administration of medications

- Foley catheter insertion to monitor urine output, as oliguria or anuria may indicate renal hypoperfusion

- Medical therapy

- Analgesia

- Pain control is crucial. Morphine is the preferred analgesic as it controls pain and decreases sympathetic tone, which helps reduce blood pressure and heart rate.

- Heart rate and blood pressure control

- Short-acting intravenous beta blockers (eg, esmolol or labetalol) are the first-line agents. The goal is to maintain a heart rate of approximately 60 beats per minute to reduce the force of left ventricular ejection against the aortic wall.

- Beta blockers should be used with caution in the setting of acute aortic regurgitation, where compensatory tachycardia may be beneficial for maintaining cardiac output.

- If beta blockers are contraindicated (eg, in patients with severe asthma or bronchospastic disease), nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers like diltiazem can be used as alternatives.

- Short-acting intravenous beta blockers (eg, esmolol or labetalol) are the first-line agents. The goal is to maintain a heart rate of approximately 60 beats per minute to reduce the force of left ventricular ejection against the aortic wall.

- Blood pressure target

- Systolic blood pressure should be lowered between 100 and 120 mm Hg, provided end-organ perfusion is not compromised. If additional blood pressure control is needed, nitroprusside can be added to the beta-blocker regimen. Other vasodilators, like nicardipine, may also be used.

- Management of hypotension

- In hypotensive patients, intravenous fluid resuscitation is the first approach. However, excessive fluid can exacerbate aortic wall stress, so caution is warranted. If hypotension persists, vasopressors (eg, norepinephrine) can be administered to maintain perfusion, but these agents should be used carefully as they can increase the force of ventricular contraction and potentially worsen the dissection.

- Analgesia

Definitive Treatment Based on AAD Classification

The type and location of the dissection—classified by the Stanford or DeBakey systems—determine the need for surgical or medical intervention.

- Stanford type A dissections (involving the ascending aorta)

- Urgent surgical intervention

- Type A dissections are considered surgical emergencies due to the risk of catastrophic complications such as cardiac tamponade, severe aortic regurgitation, myocardial infarction, or aortic rupture. Surgical mortality varies from 5% to 20%. Surgical intervention involves:

- Excision of the intimal tear

- Remove the primary tear site and obliterate entry points into the false lumen to prevent further propagation.

- Aortic replacement

- Placement of a synthetic graft to reconstitute the aortic architecture

- Aortic valve assessment and repair/replacement

- If the dissection extends into the aortic root or involves the aortic valve, valve repair or replacement with a prosthetic valve may be necessary. The decision to perform a Bentall procedure (combined aortic root and valve replacement) is based on the extent of root involvement.

- Excision of the intimal tear

- Type A dissections are considered surgical emergencies due to the risk of catastrophic complications such as cardiac tamponade, severe aortic regurgitation, myocardial infarction, or aortic rupture. Surgical mortality varies from 5% to 20%. Surgical intervention involves:

- Management of aortic arch involvement

- AADs that extend into the aortic arch are among the most complex to manage surgically, given the need for cerebral protection and the higher risk of neurologic complications, including paraplegia.

- Urgent surgical intervention

- Stanford type B dissections (involving the descending aorta)

- Medical management

- Uncomplicated type B dissections are typically managed with aggressive blood pressure and heart rate control. The goal is to reduce aortic wall stress, prevent progression, and monitor for complications.

- Indications for intervention

- Endovascular or surgical intervention is indicated for:

- Malperfusion syndromes

- Dissections causing ischemia to organs such as the kidneys, intestines, or limbs require urgent intervention.

- Aortic rupture or impending rupture

- Rapid expansion, recurrent pain, or signs of contained rupture mandate immediate repair.

- Malperfusion syndromes

- Endovascular or surgical intervention is indicated for:

- Interventions

- Endovascular stent-grafting

- Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) is preferred for complicated type B dissections.[2][21][22] TEVAR involves placing a stent-graft to seal the dissection entry tear and exclude the false lumen, promoting healing and remodeling of the aorta. TEVAR is associated with significantly lower morbidity and mortality compared to open surgical repair. However, patient selection is key, as factors like anatomy, dissection extent, and complications influence outcomes.

- Surgical repair

- Open surgery for type B dissections is reserved for cases where TEVAR is not feasible or for patients with severe complications. Open repair is associated with a higher risk of paraplegia due to potential spinal cord ischemia.

- Endovascular stent-grafting

- Medical management

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of aortic dissection include the following conditions:

- Myocardial infarction

- Aortic aneurysm

- Cardiac tamponade (from another cause)

- Esophageal rupture (Boerhaave syndrome)

- Spontaneous pneumothorax

- Pulmonary embolism

- Stroke or transient ischemic attack

Prognosis

The prognosis of aortic dissection varies significantly depending on multiple factors, including the type and location of the dissection, timing of intervention, and presence of complications. Acute aortic dissection is associated with high morbidity and mortality, particularly when diagnosis and management are delayed. A prompt and accurate diagnosis followed by appropriate treatment can markedly improve survival outcomes.

Prognosis Based on Dissection Type

- Stanford type A dissections

- Mortality without treatment

- Type A dissections are considered surgical emergencies due to the high risk of fatal complications, such as cardiac tamponade, aortic rupture, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Without intervention, the mortality rate increases by 1% to 2% per hour within the first 24 to 48 hours, reaching nearly 50% by the end of the first week.

- Surgical mortality

- With prompt surgical repair, the in-hospital mortality rate for type A dissections is around 15% to 30%, depending on factors such as patient age, presence of comorbidities, and intraoperative complications. Despite successful surgical intervention, long-term mortality remains high due to risks of recurrence, progressive aortic disease, and associated complications.

- Long-term outcomes

- The 5-year survival rate after surgical repair is approximately 70% to 80%, while the 10-year survival rate decreases to around 50% to 60%. Late mortality is often due to complications such as aortic aneurysms, redissection, and cardiovascular events.

- Mortality without treatment

- Stanford type B dissections

- Prognosis with medical management

- Uncomplicated type B dissections are typically managed conservatively with blood pressure control. The in-hospital mortality rate for medically managed type B dissections is around 10% to 15%. Patients who remain stable during the acute phase have a relatively favorable short-term prognosis.

- Prognosis with complications

- Complicated type B dissections, such as those associated with malperfusion syndromes, rupture, or rapid expansion, carry a higher risk of adverse outcomes. In these cases, in-hospital mortality can exceed 30% to 40% if not promptly treated with endovascular or surgical intervention.

- Long-term outcomes

- The 5-year survival rate for type B dissections is approximately 75% to 85%, but patients are at increased risk of aortic aneurysm formation, redissection, and rupture over time. Regular imaging surveillance and blood pressure control are critical to improving long-term prognosis.

- Prognosis with medical management

Prognostic Factors

Several clinical and anatomical factors influence the prognosis of patients with aortic dissection. Time to diagnosis and treatment is paramount, particularly for type A dissections, as delays in intervention significantly increase the risk of fatal outcomes due to rapid disease progression and life-threatening complications. The extent and location of the dissection also play a crucial role in prognosis, with dissections involving the aortic arch or extending into the abdominal aorta carrying a higher risk of complications, including organ malperfusion, neurologic deficits, and increased surgical complexity. The presence of complications such as pericardial tamponade, acute aortic regurgitation, myocardial infarction, stroke, or malperfusion syndromes is strongly associated with poor outcomes and increased mortality. Patient demographics and comorbidities, such as advanced age, history of hypertension, connective tissue disorders (eg, Marfan syndrome), and chronic kidney disease, further contribute to a worse prognosis. In particular, patients with genetic conditions like Marfan syndrome have an elevated risk of redissection and aneurysm formation, necessitating closer monitoring and follow-up. Hemodynamic status at presentation is a critical prognostic factor. Hypotension or shock at the time of diagnosis indicates severe complications, such as aortic rupture or tamponade, and is linked to a markedly increased risk of mortality. Similarly, surgical and postoperative complications, including neurologic deficits like stroke or spinal cord ischemia, renal failure, or prolonged intubation, are associated with elevated perioperative mortality and adverse long-term outcomes.

Even after successful initial treatment, patients remain at risk for long-term complications, including redissection and aneurysm formation. Recurrent dissection or aneurysmal dilation at the site of the initial dissection or other segments of the aorta is a significant concern, particularly in patients with residual dissection in the descending aorta or those with connective tissue disorders. Chronic aortic enlargement due to a residual false lumen can lead to progressive dilation, rupture, or the need for reintervention. Furthermore, these patients are at increased risk for subsequent cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure, particularly if the dissection involves the coronary arteries or aortic valve. Up to 20% to 30% of patients may require reintervention within 5 years due to recurrent dissection, aneurysm repair, or complications arising from the initial surgical or endovascular procedure. Regular follow-up with imaging and diligent management of modifiable risk factors is crucial to mitigating these risks and improving long-term outcomes.

Long-Term Complications and Recurrence Risk

Despite successful initial treatment, patients with aortic dissection remain at risk for long-term complications. One of the primary concerns is the possibility of redissection or aneurysm formation, either at the site of the initial dissection or in other segments of the aorta. This risk is particularly elevated in patients with connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome, or those with residual dissection in the descending aorta, which can predispose them to subsequent aortic pathology. Chronic aortic enlargement is another significant issue, particularly in patients with a persistent false lumen. Over time, the false lumen can lead to progressive aortic enlargement, ultimately resulting in aneurysmal dilation and, in severe cases, rupture or the need for additional surgical or endovascular interventions. Close monitoring with serial imaging is essential to detect these changes early and plan for timely intervention if needed.

Patients who have experienced aortic dissection are also at increased risk for subsequent cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure. This risk is especially prominent if the initial dissection involves the coronary arteries or the aortic valve, which can compromise cardiac function over time. Managing cardiovascular risk factors aggressively and maintaining regular follow-up are crucial for these patients. Reintervention rates are relatively high in this population, with up to 20% to 30% of patients requiring additional procedures within 5 years of the initial event. Reinterventions may be necessary due to recurrent dissection, aneurysm repair, or complications stemming from the initial surgical or endovascular approach. Long-term care and diligent follow-up are essential components of managing these patients to improve outcomes and reduce the risk of severe complications.

Prognosis and Quality of Life

Results from several studies indicate that outcomes are significantly improved when managed by an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals, which may include a cardiologist, intensivist, pulmonologist, nephrologist, cardiac surgeon, interventional radiologist, and anesthesiologist. Each member of this team plays a critical role in addressing the complex, multisystem nature of aortic dissection. Pharmacists are also integral in patient education, particularly regarding the importance of blood pressure control and medication adherence, which are crucial in preventing complications and disease progression. Notably, outcomes are generally better in high-volume centers, which handle more than 5 aortic dissection cases per year, compared to smaller centers that perform fewer procedures.[23][24][25]

Despite advances in surgical and endovascular techniques that have improved survival rates, the quality of life and functional status of survivors can be compromised. Persistent pain, reduced exercise capacity, and psychological effects such as anxiety and depression are common among patients who have experienced an aortic dissection. Long-term management includes lifestyle modifications, stringent blood pressure control, and regular follow-up with imaging to detect complications early and prevent disease progression. Overall, the prognosis of aortic dissection is largely influenced by early recognition, timely intervention, and diligent long-term monitoring. Comprehensive multidisciplinary care and patient adherence to treatment plans are essential to improving survival and reducing morbidity in this high-risk population.

Complications

Common complications of aortic dissection include:

- Multiorgan failure

- Stroke

- Myocardial infarction

- Paraplegia

- Renal failure

- Amputation of extremities

- Bowel ischemia

- Tamponade

- Acute aortic regurgitation

- Compression of superior vena cava

- Death

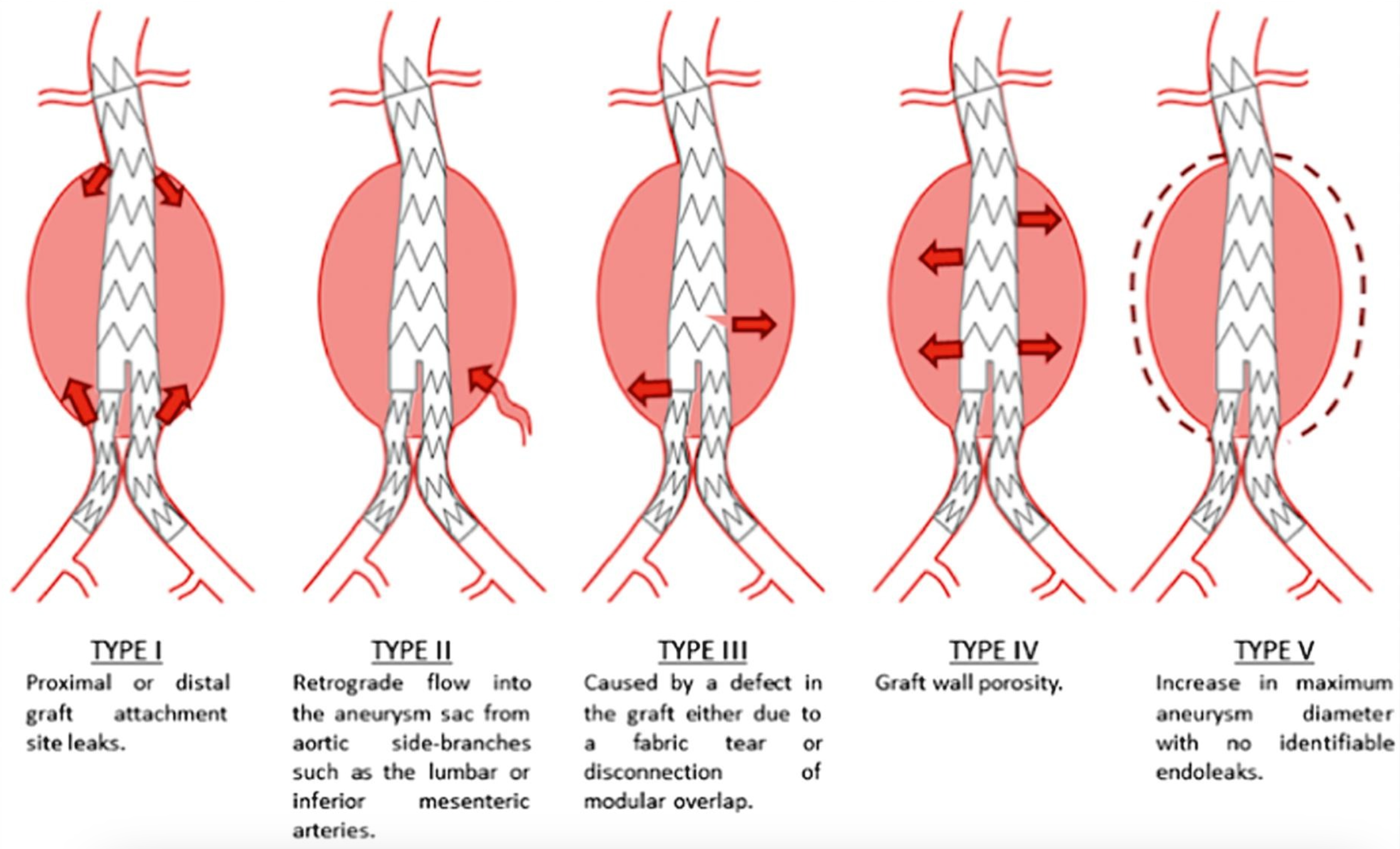

Endoleak is another common and significant complication in about 25% of patients after graft placement. An endoleak is the leakage of blood into an excluded aneurysmal sac, a term introduced by White et al. This complication can lead to aneurysm rupture over time, highlighting the need for regular imaging follow-ups for all patients after EVAR, as endoleaks may develop at any point.[26] CTA is the preferred imaging method for ongoing monitoring after EVAR. Endoleaks are categorized into 5 types, with the classification based on the source of the blood flow, which has a critical impact on subsequent patient management (see Image. Endoleak Types).[27] The type and location of endoleaks determine the management plan. Endoleaks are classified as:

- Type I

- Leakage at the attachment sites due to insufficient sealing

- IA: Proximal attachment leak

- IB: Distal attachment leak

- IC: Occurs with an aorto-mono-iliac graft and femoro-femoral bypass from the contralateral nongrafted iliac artery

- Leakage at the attachment sites due to insufficient sealing

- Type II

- Leakage through collateral vessels, such as the lumbar, inferior mesenteric, or internal iliac arteries

- Type III

- Leakage resulting from defects in the graft, including fractures or holes (mechanical failure of the graft)

- Type IV

- Leakage with no apparent source, attributed to graft porosity

- Type V

- Aneurysm expansion without visible leakage (endotension)

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative and Long-Term Management

After surgical or endovascular repair, patients require ongoing management to prevent recurrence and monitor for late complications:

- Blood pressure control

- Lifelong antihypertensive therapy is indicated to maintain a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg. Beta-blockers remain the first-line agents, and other antihypertensives, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or calcium channel blockers, may be added based on patient tolerance and comorbidities.

- Imaging surveillance

- Regular imaging follow-up with CT, MRI, or echocardiography is critical to monitor for aneurysm formation, residual dissection, or complications like endoleaks. Initial follow-up is typically performed at 3, 6, and 12 months after discharge, with annual imaging afterward.

- Lifestyle modifications

- Patients should be advised to avoid strenuous physical activity and heavy lifting to prevent increased aortic wall stress. Lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation, weight management, and adherence to antihypertensive therapy, are crucial for long-term outcomes.

- Management of complications

- Late complications such as aneurysm development, recurrent dissection, or graft complications may necessitate reintervention. Decisions should be guided by imaging findings and clinical symptoms.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Risk Factor Modification

Patients should be educated about the various modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors contributing to AAD's development. This includes:

- Hypertension management

- Hypertension is the most significant modifiable risk factor for AAD. Strict blood pressure control is crucial, typically with a target systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg. Patients should understand the importance of adhering to antihypertensive medications, dietary modifications (eg, reduced sodium intake), regular exercise, and avoiding excessive alcohol consumption.

- Avoidance of stimulants

- Cocaine and other stimulant drugs increase blood pressure and the risk of aortic dissection. Patient education should emphasize avoiding these substances and seeking help for substance use disorders.

- Atherosclerosis management

- Patients should be counseled on the importance of cholesterol management, smoking cessation, and maintaining a healthy weight. This involves regular lipid monitoring, dietary counseling, and smoking cessation support, as smoking accelerates atherosclerosis and increases the risk of dissection.

- Screening for connective tissue disorders

- Individuals with a family history of connective tissue disorders (eg, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) or genetic predispositions should undergo regular cardiovascular screening. Identifying these conditions early allows for tailored monitoring and preventive strategies, such as early elective surgical intervention in cases of progressive aortic dilation.

Patient Awareness of Symptoms

Early recognition of AAD symptoms is critical for timely intervention and reducing mortality. Patients should be educated to recognize and respond promptly to symptoms, including:

- Patients should understand that sudden, severe chest or back pain—often described as tearing or ripping—is a hallmark symptom of AAD and warrants immediate medical attention.

- They should be aware that symptoms such as sudden loss of consciousness, stroke-like symptoms, or limb weakness may indicate an aortic dissection involving branch vessels, necessitating urgent evaluation.

- Awareness of symptoms like shortness of breath, new onset of heart murmur, or signs of limb ischemia can be vital for early detection.

Encouraging patients to seek emergency care rather than waiting or self-medicating is essential for improving outcomes.

Medical Therapy Adherence and Long-term Monitoring

For patients with known aortic aneurysms or those at risk for AAD, long-term management and monitoring are key to preventing progression and complications:

- Medication adherence

- Beta-blockers are frequently prescribed to patients at risk for AAD to reduce heart rate and aortic wall stress. Patients should be counseled on the importance of adhering to their prescribed medications and understanding the rationale behind each medication to enhance compliance.

- Lifestyle adjustments

- Physical activities that significantly increase blood pressure or cause Valsalva maneuvers (eg, heavy lifting and competitive sports) should be avoided, especially in patients with a known aortic aneurysm or prior dissection. Moderate exercise, such as walking, is encouraged only after consulting with a healthcare provider.

- Regular follow-up and imaging

- Patients with connective tissue disorders or aortic aneurysms should have routine follow-ups and periodic imaging (eg, echocardiograms or CT/MRI) to monitor aortic size and integrity. Education should include the frequency and importance of these follow-ups, even without symptoms.

Genetic Counseling and Screening

For individuals with a family history of AAD or related connective tissue disorders, genetic counseling is crucial:

- First-degree relatives of patients with a history of AAD should be screened for aortic abnormalities. Genetic testing may be recommended, and positive results warrant routine surveillance and preventive measures.

- Women with a history of connective tissue disorders or aortic pathology should receive preconception counseling to assess the risk of aortic complications during pregnancy. Management strategies, such as elective repair prior to conception or high-risk obstetric care, should be discussed.

Psychosocial Support and Patient Education

The emotional burden of living with a risk for AAD or managing its aftermath can be significant. Providing patients and families with access to educational resources about AAD and support groups can improve coping mechanisms and adherence to management strategies.

Emergency Plans

Patients at high risk for AAD should have a clear emergency action plan. This includes:

- Knowing the location of the nearest hospital with advanced imaging capabilities

- Understanding when and how to call emergency services (eg, for sudden severe pain or neurological symptoms)

- Having a summary of their medical history, including prior imaging results and medications, readily available for healthcare providers in case of an emergency

Pearls and Other Issues

Despite optimal circumstances, diagnosing every case of AAD in the emergency department remains a significant challenge. One contributing factor is the variability in symptom severity, as some patients may present with relatively mild symptoms that do not immediately raise suspicion for AAD. The clinical presentation and laboratory findings may also mimic other conditions, such as acute coronary syndrome, leading to misdiagnosis. Another factor complicating diagnosis is the absence of expected physical exam findings, such as a pulse deficit or a widened mediastinum on chest x-ray, which are not always present even in confirmed cases of AAD. Every patient presenting with chest pain must be approached with the consideration that they could potentially have an AAD to minimize the risk of missed diagnoses. Establishing a detailed risk factor profile, maintaining a high index of suspicion, and being vigilant about atypical or subtle presentations are critical components of effective evaluation and diagnosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of aortic dissection requires a coordinated, patient-centered approach involving a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals, including advanced clinicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other allied healthcare professionals. Each team member enhances patient outcomes and ensures safety. Clinicians, such as cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons, lead diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making. At the same time, advanced clinicians and nurses provide continuous bedside monitoring, patient education, and early recognition of complications. Pharmacists contribute by optimizing pharmacologic therapies, ensuring medication safety, and counseling patients on medication adherence and blood pressure management, which is critical for long-term prognosis.

Open communication between team members is vital to improving outcomes.[22][28][29] Regular team meetings and a shared care plan help align treatment goals and strategies, minimizing the risk of errors and enhancing patient safety. This approach ensures that all providers are aware of the patient’s status, recent interventions, and any changes in management plans. Care coordination extends beyond the acute phase, with outpatient follow-up and rehabilitation planning guided by the team's collective expertise, including social workers and psychologists, to address psychosocial needs and support the patient’s return to daily life. By integrating the unique skills of each healthcare professional, maintaining open channels of communication, and fostering a collaborative environment, the interprofessional team can deliver comprehensive, high-quality care that enhances patient-centered outcomes and overall team performance.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Stanford Classification of Aortic Dissection. This illustration shows the proximal (Stanford A) and distal (Stanford B) classification of aortic dissection.

Npatchett, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Aortic Dissection Seen in Histology. In this case, the aortic dissection occurred in the lamina media, and there is histologic evidence of blood flow through the false lumen, as there are small thrombotic residues inside the false lumen. This image was produced using a hematoxylin-eosin stain and is magnified to 4×power.

Contributed by F Farci, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Spinelli D, Benedetto F, Donato R, Piffaretti G, Marrocco-Trischitta MM, Patel HJ, Eagle KA, Trimarchi S. Current evidence in predictors of aortic growth and events in acute type B aortic dissection. Journal of vascular surgery. 2018 Dec:68(6):1925-1935.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.05.232. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30115384]

Lau C, Leonard JR, Iannacone E, Gaudino M, Girardi LN. Surgery for Acute Presentation of Thoracoabdominal Aortic Disease. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2019 Spring:31(1):11-16. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2018.07.018. Epub 2018 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 30071280]

Wu L. The pathogenesis of thoracic aortic aneurysm from hereditary perspective. Gene. 2018 Nov 30:677():77-82. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.07.047. Epub 2018 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 30030203]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVilacosta I, San Román JA, di Bartolomeo R, Eagle K, Estrera AL, Ferrera C, Kaji S, Nienaber CA, Riambau V, Schäfers HJ, Serrano FJ, Song JK, Maroto L. Acute Aortic Syndrome Revisited: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021 Nov 23:78(21):2106-2125. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.022. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34794692]

Lombardi JV, Hughes GC, Appoo JJ, Bavaria JE, Beck AW, Cambria RP, Charlton-Ouw K, Eslami MH, Kim KM, Leshnower BG, Maldonado T, Reece TB, Wang GJ. Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Reporting Standards for Type B Aortic Dissections. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2020 Mar:109(3):959-981. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.10.005. Epub 2020 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 32000979]

Berretta P, Cefarelli M, Montalto A, Savini C, Miceli A, Rubino AS, Troise G, Patanè L, Di Eusanio M. [Surgical indications for thoracic aortic disease: beyond the "magic numbers" of aortic diameter]. Giornale italiano di cardiologia (2006). 2018 Jul-Aug:19(7):429-436. doi: 10.1714/2938.29539. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29989600]

Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J 3rd, Augoustides JG, Beck AW, Bolen MA, Braverman AC, Bray BE, Brown-Zimmerman MM, Chen EP, Collins TJ, DeAnda A Jr, Fanola CL, Girardi LN, Hicks CW, Hui DS, Schuyler Jones W, Kalahasti V, Kim KM, Milewicz DM, Oderich GS, Ogbechie L, Promes SB, Gyang Ross E, Schermerhorn ML, Singleton Times S, Tseng EE, Wang GJ, Woo YJ, Peer Review Committee Members. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022 Dec 13:146(24):e334-e482. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001106. Epub 2022 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 36322642]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBaliyan V, Parakh A, Prabhakar AM, Hedgire S. Acute aortic syndromes and aortic emergencies. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2018 Apr:8(Suppl 1):S82-S96. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2018.03.02. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29850421]

Zeng T, Shi L, Ji Q, Shi Y, Huang Y, Liu Y, Gan J, Yuan J, Lu Z, Xue Y, Hu H, Liu L, Lin Y. Cytokines in aortic dissection. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2018 Nov:486():177-182. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.08.005. Epub 2018 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 30086263]

Leonard JC, Hasleton PS, Hasleton PS, Leonard JC. Dissecting aortic aneurysms: a clinicopathological study. I. Clinical and gross pathological findings. The Quarterly journal of medicine. 1979 Jan:48(189):55-63 [PubMed PMID: 482591]

Osada H, Kyogoku M, Ishidou M, Morishima M, Nakajima H. Aortic dissection in the outer third of the media: what is the role of the vasa vasorum in the triggering process? European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2013 Mar:43(3):e82-8. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs640. Epub 2012 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 23277437]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSawabe M. Vascular aging: from molecular mechanism to clinical significance. Geriatrics & gerontology international. 2010 Jul:10 Suppl 1():S213-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00603.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20590836]

Leone O, Agozzino L, Angelini A, Bartoloni G, Basso C, Caruso G, D'Amati G, Pucci A, Thiene G, Gallo P. Criteria for histopathologic diagnosis of aortic disease consensus statement from the SIAPEC-IAP study group of "cardiovascular pathology" in collaboration with the association for Italian cardiovascular pathology. Pathologica. 2012 Feb:104(1):1-33 [PubMed PMID: 22799053]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHalushka MK, Angelini A, Bartoloni G, Basso C, Batoroeva L, Bruneval P, Buja LM, Butany J, d'Amati G, Fallon JT, Gallagher PJ, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Gouveia RH, Kholova I, Kelly KL, Leone O, Litovsky SH, Maleszewski JJ, Miller DV, Mitchell RN, Preston SD, Pucci A, Radio SJ, Rodriguez ER, Sheppard MN, Stone JR, Suvarna SK, Tan CD, Thiene G, Veinot JP, van der Wal AC. Consensus statement on surgical pathology of the aorta from the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology and the Association For European Cardiovascular Pathology: II. Noninflammatory degenerative diseases - nomenclature and diagnostic criteria. Cardiovascular pathology : the official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology. 2016 May-Jun:25(3):247-257. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2016.03.002. Epub 2016 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 27031798]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLarson EW, Edwards WD. Risk factors for aortic dissection: a necropsy study of 161 cases. The American journal of cardiology. 1984 Mar 1:53(6):849-55 [PubMed PMID: 6702637]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoberts WC. Frequency of systemic hypertension in various cardiovascular diseases. The American journal of cardiology. 1987 Sep 18:60(9):1E-8E [PubMed PMID: 2959147]

Gequelim GC, da Luz Veronez DA, Lenci Marques G, Tabushi CH, Loures Bueno RDR. Thoracic aorta thickness and histological changes with aging: an experimental rat model. Journal of geriatric cardiology : JGC. 2019 Jul:16(7):580-584. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2019.07.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31447898]

Pape LA, Awais M, Woznicki EM, Suzuki T, Trimarchi S, Evangelista A, Myrmel T, Larsen M, Harris KM, Greason K, Di Eusanio M, Bossone E, Montgomery DG, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, O'Gara P. Presentation, Diagnosis, and Outcomes of Acute Aortic Dissection: 17-Year Trends From the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015 Jul 28:66(4):350-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.029. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26205591]

Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, Bersin RM, Carr VF, Casey DE Jr, Eagle KA, Hermann LK, Isselbacher EM, Kazerooni EA, Kouchoukos NT, Lytle BW, Milewicz DM, Reich DL, Sen S, Shinn JA, Svensson LG, Williams DM, American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Society for Vascular Medicine. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2010 Aug 1:76(2):E43-86 [PubMed PMID: 20687249]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceErbel R. [Aortic diseases : Modern diagnostic and therapeutic strategies]. Herz. 2018 May:43(3):275-290. doi: 10.1007/s00059-018-4694-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29569149]

Mkalaluh S, Szczechowicz M, Dib B, Weymann A, Szabo G, Karck M. Open surgical thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: The Heidelberg experience. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2018 Dec:156(6):2067-2073. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.05.081. Epub 2018 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 30041925]

Sörelius K, Wanhainen A. Challenging Current Conservative Management of Uncomplicated Acute Type B Aortic Dissections. EJVES short reports. 2018:39():37-39. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvssr.2018.05.010. Epub 2018 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 29988823]

Piffaretti G, Bacuzzi A, Gattuso A, Mozzetta G, Cervarolo MC, Dorigo W, Castelli P, Tozzi M. Outcomes Following Non-operative Management of Thoracic and Thoracoabdominal Aneurysms. World journal of surgery. 2019 Jan:43(1):273-281. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4768-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30128772]

Gomibuchi T, Seto T, Komatsu M, Tanaka H, Ichimura H, Yamamoto T, Ohashi N, Wada Y, Okada K. Impact of Frailty on Outcomes in Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2018 Nov:106(5):1349-1355. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.06.055. Epub 2018 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 30086279]

Kim JH, Choi JB, Kim TY, Kim KH, Kuh JH. Simplified surgical approach to improve surgical outcomes in the center with a small volume of acute type A aortic dissection surgery. Technology and health care : official journal of the European Society for Engineering and Medicine. 2018:26(4):675-685. doi: 10.3233/THC-171169. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29966210]

White GH, Yu W, May J. Endoleak--a proposed new terminology to describe incomplete aneurysm exclusion by an endoluminal graft. Journal of endovascular surgery : the official journal of the International Society for Endovascular Surgery. 1996 Feb:3(1):124-5 [PubMed PMID: 8991758]

Stavropoulos SW, Charagundla SR. Imaging techniques for detection and management of endoleaks after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Radiology. 2007 Jun:243(3):641-55 [PubMed PMID: 17517926]

Kouchoukos NT. Endovascular surgery in Marfan syndrome: CON. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2017 Nov:6(6):677-681. doi: 10.21037/acs.2017.10.05. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29270380]

Krol E, Panneton JM. Uncomplicated Acute Type B Aortic Dissection: Selection Guidelines for TEVAR. Annals of vascular diseases. 2017 Sep 25:10(3):165-9. doi: 10.3400/avd.ra.17-00061. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29147169]