Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Quadriceps Muscle

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Quadriceps Muscle

Introduction

The quadriceps femoris is the most voluminous muscle of the human body.

From a sporting point of view, it is an extraordinarily important muscle, but it is often subject to trauma due to the stress it receives. The quadriceps is essential for daily activities, such as climbing stairs or getting up from a chair. Quadriceps can become a diagnostic tool in some pathological conditions, studying the intrinsic adaptations of muscle tissue. Some muscle tissue flaps can be used to repair parts of the skull or other contractile districts.[1]

Recent information on the function and anatomy of this muscle will improve the understanding of the functional coordination between the different vasti and allow the implementation of a clinical and rehabilitative approach. Its functions affect the knee joint, hip joint, posture, walking, and the relationship between the pelvis and the spine.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The actions of the quadriceps femoris have repercussions on the knee and hip joints. The rectus femoris can flex the hip, while its synergistic action with vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius extends the knee.

The myoelectric balance of the quadriceps is essential for the correct movement of the patella.

The proprioceptive afferents of the muscle contribute to maintaining adequate posture. Recent studies show that the activation of these afferents allows the contralateral quadriceps muscle to improve its coordination, increasing postural balance. The quadriceps muscles allow an independent walk, help with stair climbing, and enable one to lift from a chair.

The rectus femoris can activate its fibers in the longitudinal mode. It can activate the proximal fibers in the absence of contraction of the most distal fibers. If the action of the quadriceps continues, it will activate the most distal fibers in the absence of the most proximal ones. It is probably a mechanism to delay the onset of fatigue.

The patellar tendon insertion of the vastus medialis is small and cannot generate a force capable of medially stabilizing the patella during knee extension. The force expressed by the vastus medialis during the extension is modest. In reality, during its contraction, it pulls the aponeurosis of the vastus intermedius, counteracting the lateral forces on the patella of the vastus lateralis. The vastus medialis acts indirectly as a patellar stabilizer, placing its contractile force on the median axis of the femur.

The strength expressed by the vastus lateralis increases with the increase in knee flexion. This mechanism is due to the length of the fibers compared to the connective structure of the muscle. Longer fibers express greater strength and make better use of the elasticity or resistance of the connective tissue. When the knee is extended, the vastus lateralis places a small force that is useful for maintaining the position with minimal effort.

The following are the functions of the quadriceps muscle:

- Knee extension

- Hip flexion

- Maintenance of posture

- Proper stage of step/gait cycle

- Maintenance of patellar stability

Anatomy

The quadriceps femoris muscle is part of the anterior muscles of the thigh, along with the sartorius muscle. It is composed of five muscle bellies.

- It consists of the rectus femoris (RS) that originates from the anterior inferior iliac spine with the direct tendon and the upper rim of the acetabulum with the indirect tendon. With a third and small tendon (reflected tendon), it attaches to the hip joint capsule anteriorly. The first 2 RS tendons continue downward with two aponeurotic laminae, up to two-thirds of the rectus femoris. The direct tendon will become the superficial lamina, while the indirect tendon continues as a central sagittal lamina.[2]

- The vastus lateralis (VL) originates from the lateral face of the great trochanter, the gluteal tuberosity, and the lateral lip of the linea aspera.[3]

- The vastus medialis (VM) runs from the anatomical neck of the femur and the medial lip of the linea aspera. The vastus medialis is deeply inserted in the aponeurosis of the vastus intermedius, while the tensor of the vastus intermedius is inserted in the same aponeurosis, more superficial.

- The vastus intermedius (VI) originates from the proximal three-fourths of the anterior and lateral faces of the femoral body and the lateral lip of the linea aspera. Some bundles of the vastus intermedius are inserted in the upper recess of the supra-patellar bursae, making up the articular muscle of the knee.

The four heads are directed downward to form a single tendon, the quadriceps muscle tendon, which fits on the patella. The most superficial fibers of the tendon continue and cover the patella, inserting on the tibial tuberosity called the patellar ligament. The connective fibers of the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis attach themselves to the margins of the patella; the connective fibers of the vastus intermedius insert at the base of the patella. Some connective fibers come from the RS and, together with connective fibers of vastus lateralis/vastus medialis, will form the lateral and medial retinacula of the patella.

- Recently, another muscle, the tensor of the vastus intermedius (TVI), has been identified as part of the quadriceps femoris. The tensor of the vastus intermedius starts from the anteroinferior portion of the great trochanter. It joins with a wide flat aponeurosis between vastus lateralis and vastus intermedius in the central area of the thigh, and they join with a single tendon in the upper part of the patella, merging into the quadriceps tendon. At the dorsal level of the thigh, the muscle fibers of these three muscles merge in the vicinity of the linea aspera of the femur. At the level of the great trochanter, this muscle also can originate from the gluteus minimus.

We do not know much about its functions; however, it probably allows, together with the other aspects, a correct movement of the patella and/or puts the intermedius muscle in tension.[4]

Embryology

The limb buds exit from the ventrolateral surface of the body wall. The gems contain the mesenchyme of somatopleural, covered by an apical ectodermal crest. The cells of the hypomere (ventral part of the myotome of a somite) migrate from the somite inside the buds to form the muscle cells. The connective tissue of the limbs derives from the mesenchyme of the somatopleural. This happens around the fifth week of gestation. The gems rotate about 90 degrees medially, along with a longitudinal axis. This movement of the knee area will be located in the front portion.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The femoral artery nourishes the quadriceps muscle. It represents the continuation of the external iliac artery (behind the inguinal ligament). It descends in the anteromedial portion of the thigh to the ring of the adductor channel, where it becomes a popliteal artery. It is possible to imagine the femoral artery as a straight line connecting the center of the inguinal canal to the posterior portion of the medial condyle of the femur. Among its most important branches for the quadriceps muscle, we mention the superficial and deep femoral artery.[5]

The femoral vein is the continuation of the popliteal vein, to arrive, following the path of the femoral artery, up to the inguinal ligament, and become the external iliac vein.

The lymphatic vessels of the lower limb reach the lumbar aortic lymph nodes, which are part of the right and left lumbar trunks; drainage will reach the cisterna chyli.

Nerves

The femoral nerve originates from L2 to L4, innervating the contractile areas of the thigh anteriorly (quadriceps muscle, sartorius muscle), of the hip (comb), and the skin in the anteromedial portion of the thigh, knee, leg, and the back of the foot. It also contains fibers from L1. The roots converge downward and sideways in the thickness of the large psoas muscle, joining in a single trunk near the transverse process of L5. The formed nerve descends and exits caudally from the outer portion of the psoas muscle and continues traveling caudally in the middle of the psoas/iliac muscle complex. This area is covered by the iliac fascia, which separates it from the parietal peritoneum, the cecum colon on the right, and the sigmoid colon on the left.[6]

The fascial system that constitutes the nerve involves the tissues it crosses from the electrical point of view and the mechanical point of view. This is because a reduction in its elasticity will decrease the ability of the joints involved in its passage to move. When an entrapment syndrome is recorded, the nerve acts like a fascial brake.

Arriving at the inguinal ligament, the femoral nerve follows the iliopsoas musculature and divides into some ramifications at about 2 centimeters beyond the inguinal ligament, medial to the sartorius muscle, and lateral to the femoral artery. The nerve in this area is wider and flattened; in some subjects, the nerve can become arborized before it passes the inguinal ligament. At this level, the femoral nerve gives small superficial ramifications to the skin and the fascial structures.

Before branching, the femoral nerve enters (having passed the inguinal ligament) into the femoral lacuna (consisting of the femoral nerve and the iliopsoas muscle complex).

It continues in the Scarpa triangle or femoral triangle (pyramidal fossa with the caudal oriented apex found in the anterosuperior and medial area of the thigh, where the apex is formed by the adductor and sartorius muscle, the lateral portion consists of the sartorius muscle, and the medial one from the long adductor). Here there are vessels and lymphatic pathways (the Cloquet lymph node).

The ramifications of the femoral nerve are found for the most part in the Scarpa triangle, where we find the medial sartorius nerve, the pectineus nerve, the medial and lateral musculocutaneous nerve, the femoral nerve directed to the quadriceps muscle branches by the various vasti muscles, and the saphenous nerve.

The femoral nerve directed to the vastus lateralis is divided into two branches, which will divide into two other branches, each with a course from anteriorly and proximally to posteriorly and distally.

The femoral nerve innervating the vastus medialis follows the anteromedial border of the muscular district. The vastus intermedius receives innervation from the femoral nerve, which arrives in the medial portion of the vastus. The tensor of the vastus intermedius is innervated starting from its proximal portion. The rectus femoris receives innervation near the anterior inferior iliac spine.

Muscles

The femoral quadriceps muscle has more superficial anaerobic fibers while going to the depth, and there will be more aerobic fibers. The first fibers are less vascularized than the oxidative fibers; the white fibers will be activated after the activation of the red fibers. During a contraction, there will be slower deoxygenation of the deeper fibers.

Men express a greater percentage of contractile strength and speed than women, probably because men have greater muscle mass for men and hormone levels. Testosterone facilitates the speed of the motor unit's electrical impulse, promotes a greater amount and speed of calcium release within the fibers (faster contraction), and stimulates a faster repair process and a larger hypertrophic response. In men, the percentage of white fibers is higher.

Physiologic Variants

The Tensor of the Vastus Intermedius

The tensor of the vastus intermedius can be classified into four morphological types based on the position of the aponeurosis.

- The first type, or independent form, originates from the upper portion of the intertrochanteric line and the anterior portion of the great trochanter. Its origin is separated from the origin of the vastus intermedius in about 33% of the population. The fascia or aponeurosis remains separated from the vastus lateralis and the vastus intermedius.

- The second type originates together with the vastus intermedius; the aponeurosis is separable from the vastus lateralis. This morphology involves about 8% of the population.

- In the third type, the muscle originates from the vastus lateralis, while the aponeurosis is separable from the vastus intermedius. The percentage is around 30%.

- The typology of type four, or common typology, originates from the vastus lateralis, with the aponeurosis separable from the lateral vastus and the vastus intermedius. The finding is about 27%.

Vastus Medialis

According to some authors, the vastus medialis can be divided into vastus medialis obliquus and vastus medialis longus, based on the orientation of the fibers. The first portion is more innervated than the second portion.

Vastus Lateralis

In the literature are not reported important changes in the vastus lateralis. Its origin and insertion remain constant, as studies on cadavers confirm.

Vastus Intermedius

This portion of the quadriceps muscle may exhibit variations in its insertions or origin. It may present with a smaller area of the femur or wider attachment; it can involve the vastus lateralis in its origin, forming a single origin of the two vasti.

Rectus Femoris

The rectus femoris may have accessory muscles. A muscle slip could result from the acetabulum and fit directly into the vastus lateralis. Two distinct muscular districts could constitute the rectus femoris. Its origin may vary from deriving from the upper anterior iliac spine to deriving only from the lower anterior iliac spine in the absence of the acetabular origin. The vastus could fit directly into the vastus intermedius.

Surgical Considerations

Quadriceps Tendon Ruptures

Distal quadriceps tendon ruptures most commonly occur in patients over 40 years of age. Distal quadriceps tendon ruptures most commonly occur at its insertion point at the superior pole of the patella and have an incidence rate greater than that of its patellar tendon rupture counterpart.[7][8]

Unless medical comorbidities preclude the overwhelming benefits and positive outcomes from primary repair, surgical intervention is recommended. Indications for nonoperative management are limited to partial tears when the patient still has an intact extensor mechanism. In the latter situation, the patient can be placed in a knee immobilizer or a hinged knee brace locked in extension for 2 to 3 weeks, depending on the degree of partial injury. After repeat clinical evaluation, the patient is immediately prescribed a rigorous physical therapy regimen to combat impending knee stiffness and quadriceps atrophy. Until the patient can demonstrate adequate quadriceps muscle control, the knee brace is to be worn during ambulation. Once the quadriceps demonstrate post-rehabilitation strength comparable to the contralateral extremity, the brace serves an assisting role in augmenting the dynamic stability of the knee joint itself. Any injuries affecting muscles, tendons, or ligaments crossing the knee joint (in this case, the quadriceps functionally crosses the knee joint via the extensor mechanism and patellar tendon) should be treated following the same rehabilitation clinical pearls and parameters.

The same rehabilitation parameters mentioned above are accurate in the postoperative period following primary repair. Immediately following the repair, patients are kept in a brace locked in extension for about two weeks and allowed to weight bear as tolerated (WBAT) with bilateral crutch assistance. Physical therapy starts at this time in the postoperative period, utilizing quad stimulation modalities to help mitigate prolonged atrophy. The therapist also should be working on aggressive patellar mobilization in all directions. Patellar mobility is imperative as this plays a critical role in preventing knee stiffness. Keeping the actual patella itself mobile as the knee remains limited secondary to pain and immobility during the entire recovery period is crucial in giving the patient the best chance of achieving the best possible outcome. Early passive range of motion (ROM) is performed by the therapist, focusing on getting the knee "straight" to terminal extension and progressively increasing flexion goals from week to week (as defined by the surgeon). No active knee extension is allowed at least for the first four weeks to protect the surgical repair as the tendon is allowed to heal. Active flexion is again defined by the surgeon and starts early on in the rehab process.

While individual therapy protocol will vary based on the operating surgeon, most begin more aggressive increases in active and active-assist knee flexion goals by week 5, when they may institute active knee extension exercises. Aquatic therapy often allows for early active knee extension protocols. By six weeks, most surgeons aim for unlocking the knee brace progressively with ambulation. This usually begins by weeks 5 or 6, to hopefully achieve ROM 0 to 120 by weeks 6 to 8 postoperatively. A 2008 study outlined ROM goal parameters to 50 consecutive patients with either quad or patellar tendon rupture repairs. Both groups of patients hit the 0 to 120-degree ROM mark between 7 and 8 weeks postoperatively. By 12 weeks, all 50 patients achieved knee flexion equal to or within 10 degrees of the normal contralateral knee. By six months, 80% of patients demonstrated no evidence of any residual extensor lag.[8]

Setting patient expectations with respect to the recovery process is important. According to the literature, recovery is very slow and unsatisfactory for the patient, regardless of the surgical approach. One of the causes is the pain that could persist and the presence of scar tissue and adherence to the tendinous tissue. This leads to an inability to completely use the quadriceps muscle and the partial loss of proprioceptive information useful to the muscle. Patients reporting an unsatisfactory outcome is overwhelmingly secondary to an extensor lag and knee stiffness that compromises the ability to either return to sport (at prior competition level) or return to baseline recreational activity and/or ADLs.

Other Surgical Considerations

Surgical Approaches in Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA)[9]

The most common approaches for the standard primary TKA procedure include the medial parapatellar, midvastus, and subvastus approaches. While each approach has theoretical advantages and disadvantages, overall, the literature remains controversial concerning the best overall surgical approach for TKA.

The medial parapatellar approach is commonly utilized and entails proximal dissection through a medial cuff of the quadriceps tendon to facilitate superior tissue quality closure at the conclusion of the procedure. Distally, a meticulous, continuous medial subperiosteal dissection sleeve is performed while maintaining intimacy with the proximal tibial bone. The extent of dissection is often dictated by the anticipated amount of deformity to be corrected. In general, this medial release is aggressive in cases of severe varus deformity and most minimal in cases of moderate to advanced valgus knee deformity. The medial meniscus is also resected with this sleeve of soft tissue.

Alternatives to the standard medial parapatellar arthrotomy include the midvastus and subvastus approaches. The midvastus approach spares the quadriceps tendon. Instead, the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) muscle belly is dissected along a trajectory directed toward the superomedial aspect of the proximal pole of the patella.

The subvastus approach also spares the quadriceps tendon and lifts the muscle belly of the VMO off the intermuscular septum. The subvastus approach preserves the vascularity of the patella and requires caution as it can limit exposure in particularly challenging cases or particularly obese patients.

Quadriceps Muscles During Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA)

Postoperatively following THA, the majority of patients report a satisfactory outcome.[10] With respect to quadriceps considerations, early rehabilitation and progressive ambulation (including gait re-training protocols) are imperative to strengthen the lower extremity muscles. Surgically, the anterior thigh is given specific attention during the direct anterior approach for THA.

The DA approach is becoming increasingly popular among THA surgeons. The internervous interval is between the tensor fascia lata (TFL) and sartorius on the superficial end and the gluteus medius and rectus femoris (RF) on the deep side. DA THA advocates cite the theoretical decreased hip dislocation rates in the postoperative period and the avoidance of the hip abduction musculature.

The disadvantages include the learning curve associated with the approach, as the literature documents the decreased complication rates after a surgeon surpasses the 100-case mark. Other disadvantages include increased wound complications in particularly obese patients with large panni (without the use of an abdominal binder), difficult femoral exposure, the risk of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) paresthesias, and a potentially higher rate of intra-operative femur fractures. Finally, many surgeons need access to a specialized operating table with appropriately trained personnel and surgical technicians to assist in the procedure. Although the latter is not always required, learning to do the procedure on a regular operating table also requires a substantial learning curve that must be considered.[11]

Reconstruction of Quadriceps Muscle

Sarcomas are a type of cancer that may occur in the anterior compartment of the thigh. The surgeon can choose which muscle flap to remove from the lower limb to reconstruct that part of the sectioned quadriceps muscle. The decision will depend not only on the surgeon's technique but also on the size and depth of the tumor. The prognosis of recovery of the quadriceps functions is never positive because strength and muscle mass are lost, and persistent pain, scars, and adherence makes the movement of the limb more disadvantaged.

Following trauma, the need to rebuild part of the muscle may arise. The prognosis will always be negative, with a recovery that will depend on the extent of the surgery.

Another cause of quadriceps surgery is the repair of the rectus femoris. The latter vastus is rich in white fibers and can produce significant force, particularly during an eccentric contraction. In sports where movements are required, such as sudden decelerations or slowing down to counteract a critical load, the possibilities of muscle breakdown, total or parcel, increase. In those cases where the patient requires functional restoration, reconstruction surgery is used. According to the few data in the literature, the prognosis may be good, but the presence of scar and adherence could alter the original function of the rectus femoris.

Muscle Flap

Recent literature has shown that using the quadriceps muscle flap (vastus intermedius) is effective for reconstructing an area of the neurocranium (after trauma or resection of tumors and for aesthetic objectives). We have no data on the functional recovery of the quadriceps muscle.

The quadriceps muscle flap can be used to repair the portion of the gluteus medius.

During prosthetic hip implantation or a hip surgery for resection of tumors or the detachment of the insertion of the gluteus medius from the great trochanter, the latter muscle may be injured, compromising its function. To avoid loss of abductive function of the hip and in the active presence of the superior gluteal nerve, it is feasible to use a quadriceps muscle flap (generally the vastus lateralis) to create a useful compensation for walking.

Other General Surgical Considerations

Any time surgery is performed, an emphasis is placed on the recovery process. This includes more subtle examples, for example, non-extremity-based surgeries like bariatric surgery. Bariatric surgery, for example, gastric bypass, although it may improve physical function in general, involves a loss of mass and strength of the quadriceps muscles. This means a loss of coordination between the different vasti, increasing possible patient falls. Muscle recovery (mass and strength) should be taken into consideration in this type of patient.

More obvious scenarios include any lower extremity surgery, including the surgeries mentioned above, and arthroscopic procedures such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) reconstruction.

ACL Reconstruction

Following ACL reconstruction, recovery to the original function is very slow, and it is not always possible to completely recover the contractile function. Half of the athletes who undergo surgery do not return to previous performance levels; of the latter, about 20% to 30% will resort to a second operation or develop osteoarthritis problems over ten years.

Several rehabilitative approaches are used to restore the function of the quadriceps, but they are not always effective, such as isokinetic, electrostimulation, or exercises that try to segment the work on each vastus muscle.

In reality, it is necessary to perform exercises that reflect the functions of the muscle, both as a range of movements (movements capable of exhaustively exploiting shortening and full elongation) and as a usual neuromotor intervention (athletic gesture or daily gesture, without non-physiological stimuli such as isokinetic or electrostimulation).

Furthermore, the different metabolic structure of the muscle must be considered, such as red fibers and white fibers. One should include strength training exercises to recover strength, coordination, and muscle mass, while for aerobic metabolism and endurance exercises, one does not exclude the other.

PCL Reconstruction

After the surgical reconstruction of the posterior cruciate ligament, the functional recovery of the quadriceps is faster, although there is an incomplete recovery of strength and muscle mass. One theory is that the proprioceptive afferents of the injured anterior cruciate ligament cannot send adequate information to the central nervous system compared to the posterior ligament. Probably, there would be a greater receptor complexity for the anterior ligament in relation to the function of the quadriceps muscle.

Clinical Significance

A manual test to evaluate the femoral nerve is the sign of Nachlas. The patient is prone while the operator grabs the ankle, bending the knee with the thigh resting on the bed and bringing the heel closer to the buttock. If a radial pain in the thigh is recorded anteriorly, it may indicate the presence of compression or irritation to the femoral nerve; if other symptoms appear in the buttock or on the articular sacroiliac level, the problem must be sought elsewhere.

Another evaluation can be performed with the patient resting on the side. The operator, from behind, grasps the thigh of the side not in support, bringing the limb towards the extension, first with the knee extended and then using the same maneuver with a knee flexed. Flexion of the knee and extension of the hip causes traction of the femoral nerve; the pain radiating on the anterior portion of the thigh denotes a problem at the root of L3 in particular, while the symptomatology elicited in the medial tibial area shows issues related to L4. Possible symptomatology on the opposite side during the execution of the test would indicate a contraction was suffered or a contralateral root irritation.

Exams

Manual clinical evaluation is not sufficient to differentiate minor traumas or limit the size of a lesion. X-rays are useful in patients of peri-pubertal age, as it allows the practitioner to see any apophyseal detachments that are typical of the age group. Intramuscular calcifications of the quadriceps muscle also can be seen.

Because of the costs, MRI remains the secondary choice, although it may evaluate the different types of tissue.

Ultrasound of the muscle has low costs and good visibility of the soft tissues, and the absence of contraindications. It also allows the practitioner to evaluate the muscles with different positions and contractions, comparing the healthy side in cases of doubt. It is feasible to visualize the presence of hematomas, which, if large and untreated, can produce fibrous scar tissue, calcifications, and pseudocysts.

Classifications of Muscle Injuries

Muscle injuries can be divided into the following three causes:

- Direct trauma

- Indirect trauma (stretching and tearing)

- Lacerations

Direct traumas or contusions are divided into light, moderate, or severe, based on the limitation of the joint movement that these traumas cause. In addition to scars, a complication of direct traumas not appropriately treated is myositis ossificans. The vastus lateralis and intermedius are the vastii most affected by traumas during sports activities, being the most exposed.

Indirect traumas are divided into three classes based on the number of muscle fibers involved.

- The first degree involves a reduced number of lacerated fibers. Generally, the first-degree lesion does not increase the size of the muscle.

- The second degree of injury involves three-quarters of the muscular area. In the second degree, there may be a localized increase in muscle volume.

- The last degree exceeds the previous dimension, with the possibility of complete rupture of the muscle or the muscle-tendon junction. In the third degree, the retraction of the involved muscular district is observed.

The rectus femoris is the muscle portion most involved in indirect lesions, and in 60% of patients, the trauma involves the most proximal area. The distal area of the rectus femoris will be affected in 10% of cases, with a lesion level of the third degree.

Complete rupture of the quadriceps muscle is rare in athletes; it is easier to find this type of lesion in elderly patients or those using steroids or with systemic diseases. A complete rupture of a vastus could occur in asymptomatic mode, mimicking another problem. For example, the appearance of back pain with anterior irradiation of the leg, as reported in the literature. A total rupture of a vastus or more vastii could result from worsening hypertrophy caused by an existing disease, for example, neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis or an orthopedic disease such as ankylosing spondylitis.

Other Issues

Adaptations of the Quadriceps Muscle in the Presence of Disease

Skeletal muscle adapts in the presence of systemic diseases. This means that the function of the muscle changes both metabolism and volumes, worsening the symptomatic picture.

As has been demonstrated in chronic respiratory and cardiac diseases, there is no direct correlation between the symptom (dyspnea and fatigue) and the values of the cardiac function (ejection rate) and pulmonary function (FEV1). It is the musculature that determines, over time, the manifestation of the disease, fatigue, and dyspnoea. Knowing how to adapt the muscles allows better orientation during the rehabilitation process.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

The presence of chronic and ingravescent respiratory diseases such as COPD determines a decrease in muscle mass of the quadriceps femoris muscle, an increase of the connective tissue, and fibrosis phenomena. This will lead to decreased contractile capacity, less strength, and less balance during walking or standing posture. The anaerobic fibers will increase at the expense of the oxidative fibers; the muscles will be more easily fatigued. It increases intramuscular fat with local and systemic metabolic alteration (increased cardiovascular risk). The female gender will suffer more from the functional alteration of the muscle than the male gender.

Chronic Heart Failure

In patients with chronic heart failure (CHF), there are very similar muscular changes to chronic respiratory diseases. The muscle mass decreases, as well, as the red fibers decrease. Muscle cells have less ability to repair themselves, with a constant inflammatory pattern. The quadriceps has less strength and less neuromuscular control.

Diabetes

In the quadriceps muscle of patients with diabetes, a functional alteration occurs, with loss of volumes, precocious senescence of the muscle cells (primarily for women), and a greater decrease for the oxidative fibers in a cellular environment with inflammation and strong oxidation. Exhaustive neuromuscular coordination is lost with an increased rate of falls.

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is characterized by the absence of the dystrophin protein, which is essential for muscle fiber repair. The muscular cell presents with necrotic fibers, increased intramuscular fat, and fibrosis. The quadriceps muscle loses shape and function, with diminished restorative capacity and volumes.

Multiple Sclerosis

In multiple sclerosis, the quadriceps muscle loses muscle mass and strength, with a decrease in oxidative fibers but an increase in anaerobic fibers. Although there is an increase in the number of white fibers, the latter suffer more atrophy. Increase intramuscular fat and fibrosis processes.

Aging

The muscular adaptation of the quadriceps muscle with advancing age changes its morphology and function. Tendentially, the musculature loses mass, and volume (sarcopenia) decreases strength and coordination. Motor units are lost (denervation processes) while the percentage of red fibers increases. This increases the fibrosis processes and intramuscular fat.

Fibromyalgia

Muscle cells have lower amounts of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and PCr (phosphocreatine), with less contractile capacity. There is mitochondrial suffering of red fibers and a marked hypotrophy of white fibers; DNA fragmentation; reduced capillarization with thickening of the endothelium; and increases in intramuscular fat.

The Quadriceps Muscle as a Diagnostic Tool

There is a close direct relationship between muscle mass and the capillary network; the latter directly relates to insulin sensitivity. Studies on a human model have shown that evaluating the capillarization of the quadriceps muscle can give important indications regarding the insulin sensitivity of the whole body system.

A recent study has shown that studying the quadriceps fibers to determine if inflammatory myocarditis exists is a fathomable and correct procedure. With the increase of intramuscular lymphocytes, the presence of lymphocytic myocarditis can be predicted, with a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 100%.

Knee pain Without Surgery

Patients suffering from chronic unilateral knee pain lack bilateral quadriceps muscle coordination and less resistance to effort.[12] Patients who suffer from knee pain anteriorly and who have not undergone previous operations demonstrate a reduction in strength compared to patients who have undergone previous surgery (meniscus and anterior cruciate ligament).[13]

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis demonstrate a functional slowing of the performance of the quadriceps muscle (neuromuscular incoordination) and a lower strength expressed. The quadriceps musculature appears to have fewer muscle fibers (hypotrophy) and reduced the pennation angle.[14]

Media

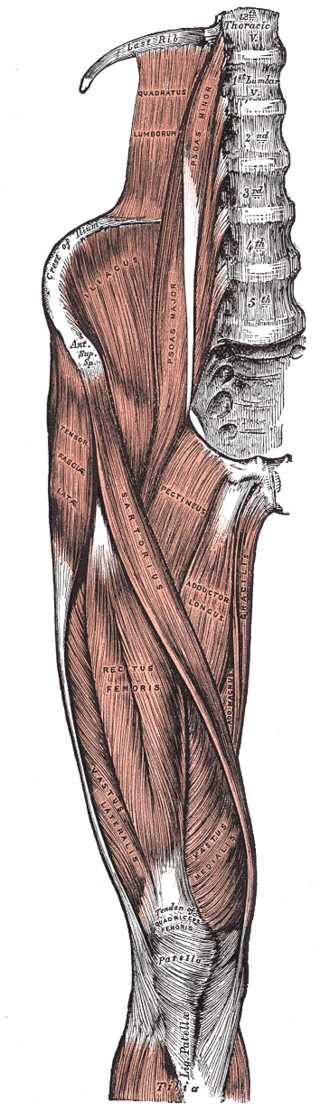

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Right Hip and Femoral Muscles, Anterior View. This illustration shows the tensor fasciae latae, thoracic vertebrae, quadratus lumborum, psoas minor and major, crest of ilium, anterior superior iliac spine, iliacus, sartorius, pectineus, adductor longus, gracilis, adductor magnus, rectus femoris, vastus lateralis and medialis, tibia, patella, and quadriceps tendon.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Deleget A. Overview of thigh injuries in dance. Journal of dance medicine & science : official publication of the International Association for Dance Medicine & Science. 2010:14(3):97-102 [PubMed PMID: 21067687]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurdock CJ, Mudreac A, Agyeman K. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Rectus Femoris Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969719]

Biondi NL, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Vastus Lateralis Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335342]

O'Sullivan ST, Harty JA. Patellar stabilization surgeries in cases of recurrent patellar instability: a retrospective clinical and radiological audit. Irish journal of medical science. 2021 May:190(2):647-652. doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02344-x. Epub 2020 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 32815116]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWilliams M, Caterson J, Cogswell L, Gibbons CLMH, Cosker T. A cadaveric analysis of the blood supply to rectus Femoris. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2019 Apr:72(4):616-621. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2018.12.045. Epub 2019 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 30658952]

Huser AJ, Kwak YH, Rand TJ, Paley D, Feldman DS. Anatomic Relationship of the Femoral Neurovascular Bundle in Patients With Congenital Femoral Deficiency. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2021 Feb 1:41(2):e111-e115. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001709. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33165261]

Boublik M, Schlegel TF, Koonce RC, Genuario JW, Kinkartz JD. Quadriceps tendon injuries in national football league players. The American journal of sports medicine. 2013 Aug:41(8):1841-6. doi: 10.1177/0363546513490655. Epub 2013 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 23735426]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWest JL, Keene JS, Kaplan LD. Early motion after quadriceps and patellar tendon repairs: outcomes with single-suture augmentation. The American journal of sports medicine. 2008 Feb:36(2):316-23 [PubMed PMID: 17932403]

Varacallo M, Luo TD, Johanson NA. Total Knee Arthroplasty Techniques. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763071]

Varacallo M, Chakravarty R, Denehy K, Star A. Joint perception and patient perceived satisfaction after total hip and knee arthroplasty in the American population. Journal of orthopaedics. 2018 Jun:15(2):495-499. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.03.018. Epub 2018 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 29643693]

Varacallo M, Luo TD, Johanson NA. Total Hip Arthroplasty Techniques. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939641]

Kim S, Park J. Patients with chronic unilateral anterior knee pain experience bilateral deficits in quadriceps function and lower quarter flexibility: a cross-sectional study. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2022 Nov:38(13):2531-2543. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2021.1946871. Epub 2021 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 34253159]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKim S, Kim D, Park J. Knee Joint and Quadriceps Dysfunction in Individuals With Anterior Knee Pain, Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction, and Meniscus Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of sport rehabilitation. 2020 Apr 1:30(1):112-119. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2018-0482. Epub 2020 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 32234996]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBlum D, Rodrigues R, Geremia JM, Brenol CV, Vaz MA, Xavier RM. Quadriceps muscle properties in rheumatoid arthritis: insights about muscle morphology, activation and functional capacity. Advances in rheumatology (London, England). 2020 May 19:60(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s42358-020-00132-w. Epub 2020 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 32429993]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence