Introduction

Thalassemias are a heterogeneous grouping of genetic disorders that result from a decreased synthesis of alpha or beta chains of hemoglobin (Hb). Hemoglobin serves as the oxygen-carrying component of the red blood cells. It consists of two proteins, an alpha, and a beta. If the body does not manufacture enough of one or the other of these two proteins, the red blood cells do not form correctly and cannot carry sufficient oxygen; this causes anemia that begins in early childhood and lasts throughout life. Thalassemia is an inherited disease, meaning that at least one of the parents must be a carrier for the disease. It is caused by either a genetic mutation or a deletion of certain key gene fragments.

Alpha thalassemia is caused by alpha-globin gene deletion which results in reduced or absent production of alpha-globin chains. Alpha globin gene has 4 alleles and disease severity ranges from mild to severe depending on the number of deletions of the alleles. Four allele deletion is the most severe form in which no alpha globins are produced and the excess gamma chains (present during the fetal period) form tetramers. It is incompatible with life and results in hydrops fetalis. One allele deletion is the mildest form and is mostly clinically silent.

Beta thalassemia results from point mutations in the beta-globin gene. It is divided into three categories based on the zygosity of the beta-gene mutation. A heterozygous mutation (beta-plus thalassemia) results in beta-thalassemia minor in which beta chains are underproduced. It is mild and usually asymptomatic. Beta thalassemia major is caused by a homozygous mutation (beta-zero thalassemia) of the beta-globin gene, resulting in the total absence of beta chains. It manifests clinically as jaundice, growth retardation, hepatosplenomegaly, endocrine abnormalities, and severe anemia requiring life-long blood transfusions. The condition in between these two types is called beta-thalassemia intermedia with mild to moderate clinical symptoms.

- One mutated gene: Mild signs and symptoms. The condition is called thalassemia minor.

- Two mutated genes: Signs and symptoms will be moderate to severe. This condition is called thalassemia major, or Cooley anemia. Babies born with two mutated beta hemoglobin genes are usually healthy at birth but disease starts to manifest after 6 months of life when fetal hemoglobin (Hb-gamma) disappears and is replaced by adult Hb.

The excess unpaired alpha-globin chains in beta-thalassemia aggregate and form precipitates that damage red cell membranes and result in intravascular hemolysis. This premature death of erythroid precursor cells leads to ineffective erythropoiesis and later results in extramedullary expansion of hematopoiesis.

Coinheritance of alpha thalassemia: Beta-thalassemia patients with coinheritance of alpha thalassemia have a milder clinical course due to a less severe alpha-beta chain imbalance.

Coexistence of sickle cell trait: The presence of sickle cell trait with beta-thalassemia is a major hemoglobinopathy and results in manifestations of sickle cell disease. Unlike sickle cell trait in which major Hb is HbA, in the co-existence state the major Hb is HbS which constitutes more than 60% of Hb depending on the nature of the disease (beta-zero or beta-plus0.)

Hemoglobin (HbE) is also a common Hb variant found in Southeast Asia population. It has a correlation with a beta-thalassemia phenotype, as people with thalassemia in this territory are commonly found to have HbE.

Two new terminologies being used more often in clinical settings are transfusion requiring and non-transfusion requiring thalassemias and all the basic classification falls into these two types depending on the requirement of frequent blood transfusions or not.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Thalassemia is autosomal recessive, which means both the parents must be affected with or carriers for the disease to transfer it to the next generation. It is caused by mutations or deletions of the Hb genes, resulting in underproduction or absence of alpha or beta chains. There are over 200 mutations identified as the culprits for causing thalassemias. Alpha thalassemia is caused by deletions of alpha-globin genes, and beta thalassemias are caused by a point mutation in splice site and promoter regions of the beta-globin gene on chromosome 11.[4]

Epidemiology

Alpha thalassemia is prevalent in Asian and African populations while beta-thalassemia is more prevalent in the Mediterranean population, although it is relatively common in Southeast Asia and Africa too. Prevalence in these regions may be as high as 10%. The true numbers of thalassemia affected patients in the United States are unknown, as there is no effective screening method in place.[4]

History and Physical

Thalassemia presentation varies widely depending on the type and severity. A complete history and physical examination can give several clues that are sometimes not obvious to the patient themselves. The following findings can be noted:

Skin

Skin can show pallor due to anemia and jaundice due to hyperbilirubinemia resulting from intravascular hemolysis. Patients usually report fatigue due to anemia as the first presenting symptom. Extremities examination can show ulcerations. Chronic iron deposition due to multiple transfusions can result in bronze skin.

Musculoskeletal

Extramedullary expansion of hematopoiesis results in deformed facial and other skeletal bones and an appearance known as chipmunk face.

Cardiac

Iron deposition in cardiac myocytes due to chronic transfusions can disrupt the cardiac rhythm, and the result is various arrhythmias. Due to chronic anemia, overt heart failure can also result.

Abdominal

Chronic hyperbilirubinemia can lead to precipitation of bilirubin gall stones and manifest as typical colicky pain of cholelithiasis. Hepatosplenomegaly can result from chronic iron deposition and also from extramedullary hematopoiesis in these organs. Splenic infarcts or autophagy result from chronic hemolysis due to poorly regulated hematopoiesis.

Hepatic

Hepatic involvement is a common finding in thalassemias, particularly due to the chronic need for transfusions. Chronic liver failure or cirrhosis can result from chronic iron deposition or transfusion-related viral hepatitis.

Slow Growth Rates

Anemia can inhibit a child's growth rate, and thalassemia can cause a delay in puberty. Particular attention should focus on the child's growth and development according to age.

Endocrinopathies

Iron overload can lead to its deposition in various organ systems of the body and resultant decreased functioning of the respective systems. The deposition of iron in the pancreas can lead to diabetes mellitus; in the thyroid or parathyroid glands can lead to hypothyroidism and hypoparathyroidism, respectively. The deposition in joints leads to chronic arthropathies. In the brain, iron prefers to accumulate in the substantia nigra and manifests as early-onset Parkinson's disease and various other physiatry problems. These symptoms fall in the vast kingdom of hemochromatosis.[5]

Evaluation

Several laboratory tests have been developed to screen and diagnose thalassemia:

Complete blood count (CBC): CBC is often the first investigation in a suspected case of thalassemia. A CBC showing low hemoglobin and low MCV is the first indication of thalassemia, after ruling out iron deficiency as the cause of anemia. The calculation of the Mentzer index (mean corpuscular volume divided by red cell count) is useful. A Mentzer lower than 13 suggests that the patient has thalassemia, and an index of more than 13 suggests that the patient has anemia due to iron deficiency.[6]

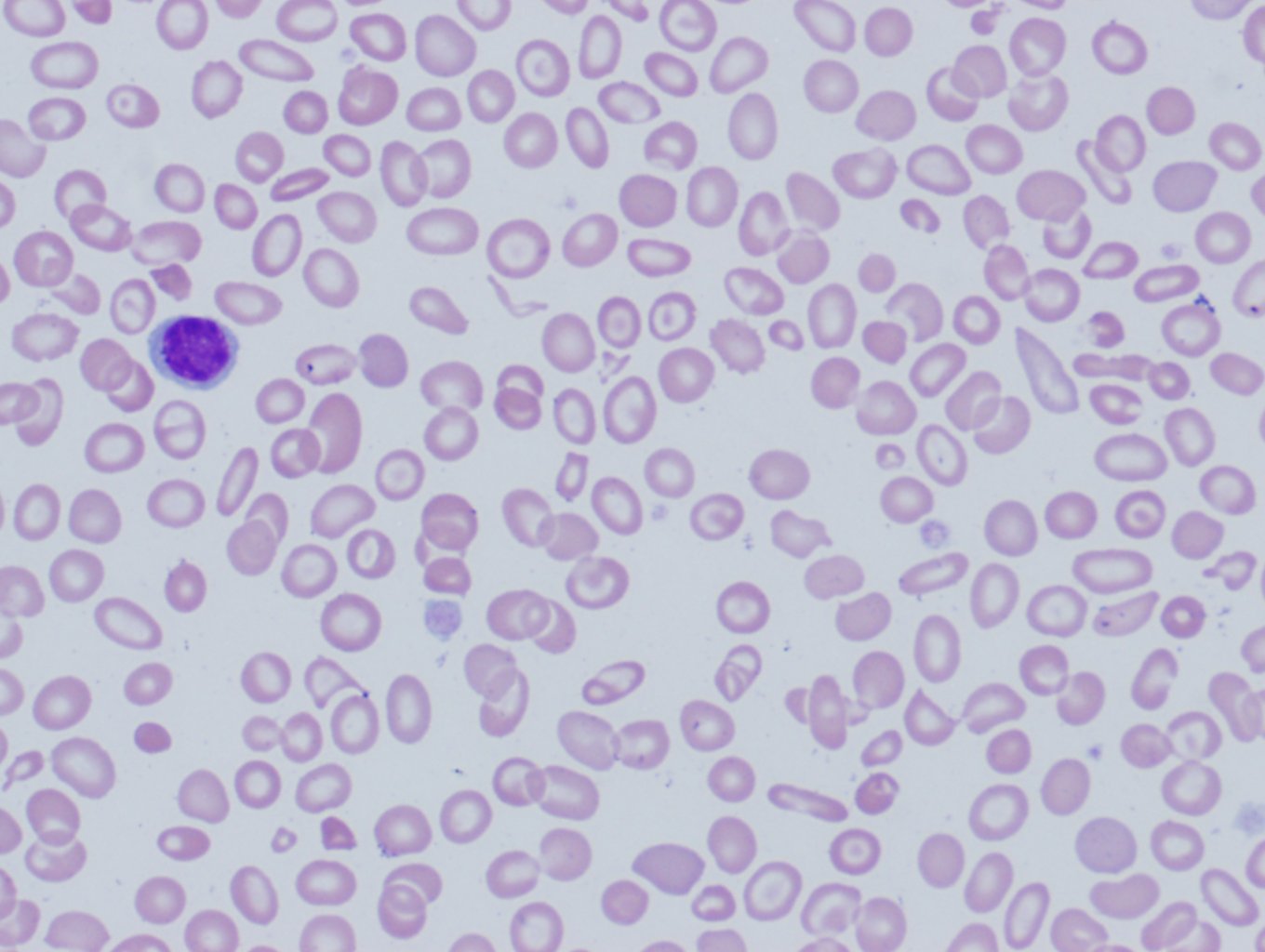

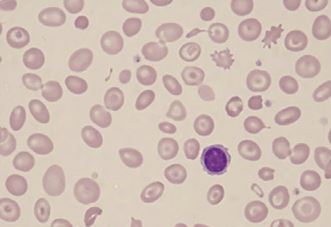

Peripheral blood smear: A blood smear (also called peripheral smear and manual differential) is next, to assess additional red cell properties. Thalassemia can present with the following findings on the peripheral blood smear:

- Microcytic cells (low MCV)

- Hypochromic cells

- Variation in size and shape (anisocytosis and poikilocytosis)

- Increased percentage of reticulocytes

- Target cells

- Heinz bodies

Iron studies (serum iron, ferritin, unsaturated iron-binding capacity (UIBC), total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and percent saturation of transferrin) are also done to rule out iron deficiency anemia as the underlying cause.

Erythrocyte porphyrin levels may be checked to distinguish an unclear beta-thalassemia minor diagnosis from iron deficiency or lead poisoning. Individuals with beta-thalassemia will have normal porphyrin levels, but those with the latter conditions will have elevated porphyrin levels.

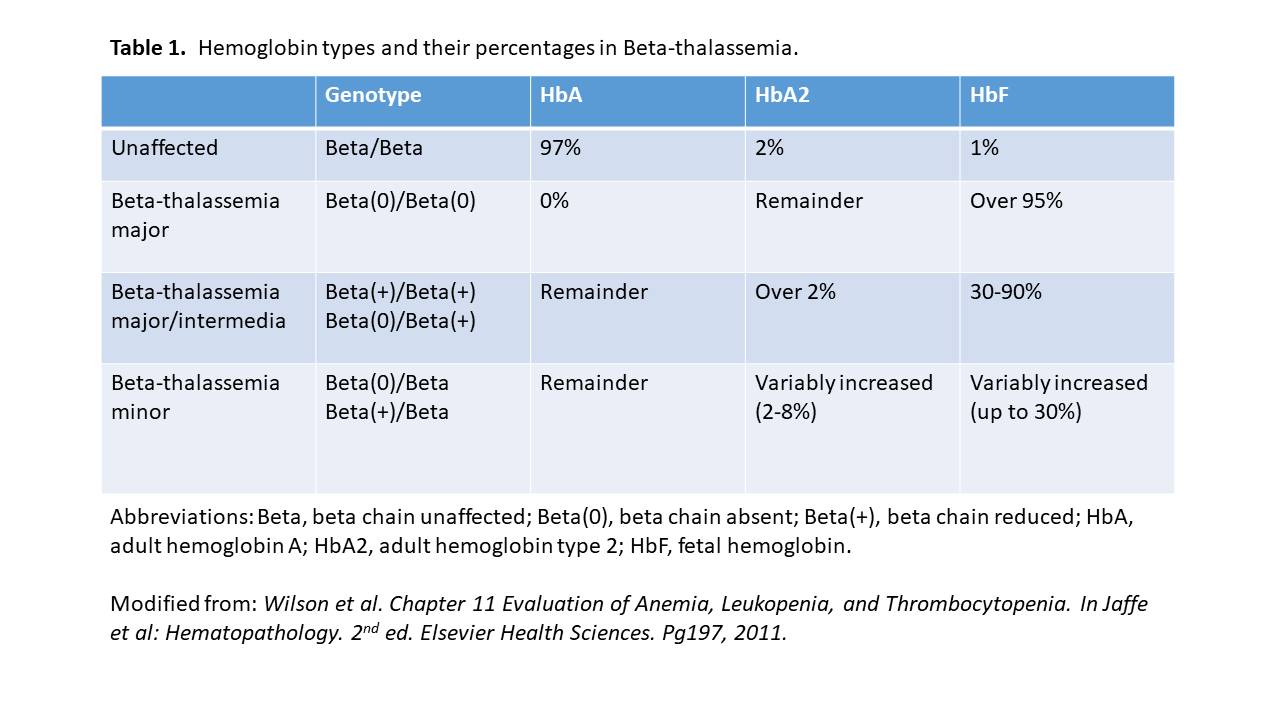

Hemoglobin electrophoresis: Hemoglobinopathy (Hb) evaluation assesses the type and relative amounts of hemoglobin present in red blood cells. Hemoglobin A (HbA), composed of both alpha and beta-globin chains, is the type of hemoglobin that typically makes up 95% to 98% of hemoglobin for adults. Hemoglobin A2 (HbA2) is normally 2% to 3% of hemoglobin, while hemoglobin F usually makes up less than 2% of hemoglobin in adults.

Beta thalassemia disturbs the balance of beta and alpha hemoglobin chain formation. Patients with the beta-thalassemia major usually have larger percentages of HbF and HbA2 and absent or very low HbA. Those with beta-thalassemia minor usually have a mild elevation of HbA2 and mild decrease of HbA. HbH is a less common form of hemoglobin that may be seen in some cases of alpha thalassemia. HbS is the hemoglobin prevalent in people with sickle cell disease.

Hemoglobinopathy (Hb) assessment is used for prenatal screening when parents are at high risk for hemoglobin abnormalities and state-mandated newborn hemoglobin screening.

DNA analysis: These tests serve to help confirm mutations in the alpha and beta globin-producing genes. DNA testing is not a routine procedure but can be used to help diagnose thalassemia and to determine carrier status if needed.

Since having relatives carrying mutations for thalassemia increases a person's risk of carrying the same mutant gene, family studies may be necessary to assess carrier status and the types of mutations present in other family members.

Genetic testing of amniotic fluid is useful in those rare instances where a fetus has an increased risk for thalassemia. This is particularly important if both parents likely carry a mutation because that increases the risk that their child may inherit a combination of abnormal genes, causing a more severe form of thalassemia. Prenatal diagnosis with chorionic villi sampling at 8 to 10 weeks or by amniocentesis at 14 to 20 weeks’ gestation can be carried out in high-risk families.[7][6]

Multisystem evaluation: Evaluation of all related systems should be done on a regular basis due to their frequent involvement in the disease progression. Biliary tract and gall bladder imaging, abdominal ultrasonography, cardiac MRI, serum hormone measurements are a few examples that can be done or repeated depending on the clinical suspicion and case description.

Treatment / Management

Thalassemia treatment depends on the type and severity of the disease.

Mild thalassemia (Hb: 6 to 10g/dl):

Signs and symptoms are generally mild with thalassemia minor and little if any, treatment is needed. Occasionally, patients may need a blood transfusion, particularly after surgery, following childbirth, or to help manage thalassemia complications.

Moderate to severe thalassemia (Hb less than 5 to 6g/dl):

- Frequent blood transfusions: More severe forms of thalassemia often require regular blood transfusions, possibly every few weeks. The goal is to maintain Hb at around 9 to 10 mg/dl to give the patients a sense of well being and also to keep a check on erythropoiesis and suppress extramedullary hematopoiesis. To limit transfusion-related complications, washed, packed red blood cells (RBCs) at approximately 8 to 15 mL cells per kilogram (kg) of body weight over 1 to 2 hours are recommended.

- Chelation therapy: Due to chronic transfusions, iron starts to get deposited in various organs of the body. Iron chelators (deferasirox, deferoxamine, deferiprone) are given concomitantly to remove extra iron from the body.

-

Stem cell transplant: Stem cell transplant, (bone marrow transplant), is a potential option in selected cases, such as children born with severe thalassemia. It can eliminate the need for lifelong blood transfusions.[8] However, this procedure has its own complications, and the clinician must weigh these against the benefits. Risks include including graft vs. host disease, chronic immunosuppressive therapy, graft failure, and transplantation-related mortality.[9]

- Gene therapy: It is the latest advancement in severe thalassemia management. It involves harvesting the autologous hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from the patient and genetically modifying them with vectors expressing the normal genes. These are then reinfused to the patients after they have undergone the required conditioning to destroy the existing HSCs. The genetically modified HSCs produce normal hemoglobin chains, and normal erythropoiesis ensues. (B2)

- Genome editing techniques: Another recent approach is editing genomic libraries, such as zinc-finger nucleases, transcription activator-like effectors, and cluster regulated interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) with Cas9 nuclease system. These techniques target specific mutation sites and replace them with the normal sequence. The limitation of this technique is to produce a large number of corrected genes sufficient to cure the disease.[10]

- Splenectomy: Patients with thalassemia major often undergo splenectomy to limit the number of required transfusions. Splenectomy is the usual recommendation when the annual transfusion requirement increases to or more than 200 to 220 mL RBCs/kg/year with a hematocrit value of 70%. Splenectomy not only limits the number of required transfusions but also controls the spread of extramedullary hematopoiesis. Postsplenectomy immunizations are necessary to prevent bacterial infections, including Pneumococcus, Meningococcus, and Haemophilus influenzae. Postsplenectomy sepsis is possible in children, so this procedure is deferred until 6 to 7 years of age, and then penicillin is given for prophylaxis until they reach a certain age.

- Cholecystectomy: Patients can develop cholelithiasis due to increased Hb breakdown and bilirubin deposition in the gallbladder. If it becomes symptomatic, patients should undergo cholecystectomy at the same time when they are undergoing splenectomy.

Diet and exercise:

Reports exist that drinking tea aids in reducing iron absorption from the intestinal tract. So, in thalassemia patients tea might be a healthy drink to use routinely. Vitamin C helps in iron excretion from the gut, especially when used with deferoxamine. But using vitamin C in large quantities and without concomitant deferoxamine use, there is a higher risk for fatal arrhythmias. So, the recommendation is to use low quantities of vitamin C along with iron chelators (deferoxamine).[10]

Differential Diagnosis

- Iron deficiency anemia: This is ruled out by iron studies and Mentzer index.

- Anemia of chronic disease and renal failure: Elevated markers of inflammation (CRP, ESR) point in this direction.

- Sideroblastic anemias: These are ruled out by iron studies and peripheral blood smear.

- Lead poisoning: This is ruled out by measuring serum protoporphyrin level.

Prognosis

Thalassemia minor is usually asymptomatic and has a good prognosis. It normally does not increase morbidity or mortality.

Thalassemia major is a severe disease, and the long-term prognosis depends on the treatment adherence to transfusion and iron chelation therapies.[11]

Complications

Thalassemia major can produce the following complications[12][13]:

- Jaundice and gall stones due to hyperbilirubinemia

- Cortical thinning and distortion of bones due to extramedullary hematopoiesis

- High output cardiac failure due to severe anemia, cardiomyopathies, and arrhythmias - cardiac involvement is the major cause of mortality in thalassemia patients

- Hepatosplenomegaly due to extramedullary hematopoiesis and excess iron deposition due to repeated blood transfusions

- Excess iron can lead to findings of primary hemochromatosis such as endocrine abnormalities, joint problems, skin discoloration, etc.

- Neurological complications such as peripheral neuropathies

- Slow growth rate and delayed puberty

- Increased risk of parvovirus B19 infection

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated to keep a check on their disease by following an appropriate treatment plan and adopting healthy living habits.

- Avoid excess iron. Unless the doctor recommends otherwise, patients should avoid multivitamins or other supplements that contain iron.

- Eat a healthy diet. Eating a balanced diet that contains plenty of nutritious foods can help the patient feel better and boost energy. Doctors sometimes also recommend taking a folic acid supplement to help make new red blood cells.

- Avoid infections. Patients should try maximally to protect themselves from infections, especially following a splenectomy. An annual flu shot, meningitis, pneumococcal, and hepatitis B vaccines are recommended to prevent infections.

Patients should also receive education about the hereditary nature of the disease. If both parents have thalassemia minor, there is a 1/4th chance that they will have a child with thalassemia major. If one parent has beta-thalassemia minor and the other parent has some form of beta-globin gene defect, i.e., sickle cell defect, they should also be counseled about the possibility of disease transfer to their children. Patients with thalassemias should understand that their disease is not due to iron deficiency and that iron supplements will not cure the anemia; in fact, it will lead to more iron buildup if they are already receiving blood transfusions.[14]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Thalassemia has negative repercussions for many organs, and without a cure, it has high morbidity. The disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a thalassemia care team, cardiologist, hepatologist, endocrinologist, and psychologist. Also, family care, nursing support, and social support are an integral part of the management. A lead consultant should be in charge of the patient care, and a nurse specialist, along with other specialists in the respective fields, should be involved to cover all the aspects of the disease. Patient education is crucial, and social worker involvement, including a geneticist, is essential. In some parts of the world, preventive strategies include prenatal screening, restrictions on issuing marriage licenses to two people with the same disease. The screening of children and pregnant women who visit clinicians is an effective strategy to limit the disease morbidity. The social worker should ensure that the caregiver/patient has adequate support and financial resources so that they can continue with treatment. Nurses should educate patients on the importance of treatment compliance to avoid serious complications, as well as monitoring treatment progress. Pharmacists may soon play a greater role as there are new drug products to assist in gene therapy on the horizon that can eliminate the need for ongoing transfusions.

Active collaboration and discussion between interprofessional team members help in the better understanding of the progression or control of the disease.[Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

He LN, Chen W, Yang Y, Xie YJ, Xiong ZY, Chen DY, Lu D, Liu NQ, Yang YH, Sun XF. Elevated Prevalence of Abnormal Glucose Metabolism and Other Endocrine Disorders in Patients with β-Thalassemia Major: A Meta-Analysis. BioMed research international. 2019:2019():6573497. doi: 10.1155/2019/6573497. Epub 2019 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 31119181]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVichinsky E, Cohen A, Thompson AA, Giardina PJ, Lal A, Paley C, Cheng WY, McCormick N, Sasane M, Qiu Y, Kwiatkowski JL. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of nontransfusion-dependent thalassemia in the United States. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2018 Jul:65(7):e27067. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27067. Epub 2018 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 29637688]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAhmadpanah M, Asadi Y, Haghighi M, Ghasemibasir H, Khanlarzadeh E, Brand S. In Patients with Minor Beta-Thalassemia, Cognitive Performance Is Related to Length of Education, But Not to Minor Beta-Thalassemia or Hemoglobin Levels. Iranian journal of psychiatry. 2019 Jan:14(1):47-53 [PubMed PMID: 31114617]

Jalil T, Yousafzai YM, Rashid I, Ahmed S, Ali A, Fatima S, Ahmed J. Mutational Analysis Of Beta Thalassaemia By Multiplex Arms-Pcr In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC. 2019 Jan-Mar:31(1):98-103 [PubMed PMID: 30868793]

Puar N, Newell B, Shao L. Blueberry Muffin Skin Lesions in an Infant With Epsilon Gamma Delta Beta Thalassemia. Pediatric and developmental pathology : the official journal of the Society for Pediatric Pathology and the Paediatric Pathology Society. 2019 Nov-Dec:22(6):599-600. doi: 10.1177/1093526619850663. Epub 2019 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 31088202]

Singha K, Taweenan W, Fucharoen G, Fucharoen S. Erythrocyte indices in a large cohort of β-thalassemia carrier: Implication for population screening in an area with high prevalence and heterogeneity of thalassemia. International journal of laboratory hematology. 2019 Aug:41(4):513-518. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.13035. Epub 2019 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 31099487]

Ansari S, Rashid N, Hanifa A, Siddiqui S, Kaleem B, Naz A, Perveen K, Hussain Z, Ansari I, Jabbar Q, Khan T, Nadeem M, Shamsi T. Laboratory diagnosis for thalassemia intermedia: Are we there yet? Journal of clinical laboratory analysis. 2019 Jan:33(1):e22647. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22647. Epub 2018 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 30221402]

Jariwala K, Mishra K, Ghosh K. Comparative study of alloimmunization against red cell antigens in sickle cell disease & thalassaemia major patients on regular red cell transfusion. The Indian journal of medical research. 2019 Jan:149(1):34-40. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_940_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31115372]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSarkar SK, Shah MS, Begum M, Yunus AM, Aziz MA, Kabir AL, Khan MR, Rahman F, Rahman A. Red Cell Alloantibodies in Thalassaemia Patients Who Received Ten or More Units of Transfusion. Mymensingh medical journal : MMJ. 2019 Apr:28(2):364-369 [PubMed PMID: 31086152]

Darvishi Khezri H, Emami Zeydi A, Sharifi H, Jalali H. Is Vitamin C Supplementation in Patients with β-Thalassemia Major Beneficial or Detrimental? Hemoglobin. 2016 Aug:40(4):293-4. doi: 10.1080/03630269.2016.1190373. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27492769]

Zhang H, Zhabyeyev P, Wang S, Oudit GY. Role of iron metabolism in heart failure: From iron deficiency to iron overload. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease. 2019 Jul 1:1865(7):1925-1937. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.08.030. Epub 2018 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 31109456]

Benites BD, Cisneiros IS, Bastos SO, Lino APBL, Costa FF, Gilli SCO, Saad STO. Echocardiografic abnormalities in patients with sickle cell/β-thalassemia do not depend on the β-thalassemia phenotype. Hematology, transfusion and cell therapy. 2019 Apr-Jun:41(2):158-163. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2018.09.003. Epub 2018 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 31084765]

Paul A, Thomson VS, Refat M, Al-Rawahi B, Taher A, Nadar SK. Cardiac involvement in beta-thalassaemia: current treatment strategies. Postgraduate medicine. 2019 May:131(4):261-267. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1608071. Epub 2019 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 31002266]

Manzoor I,Zakar R, Sociodemographic determinants associated with parental knowledge of screening services for thalassemia major in Lahore. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2019 Mar-Apr; [PubMed PMID: 31086537]