Introduction

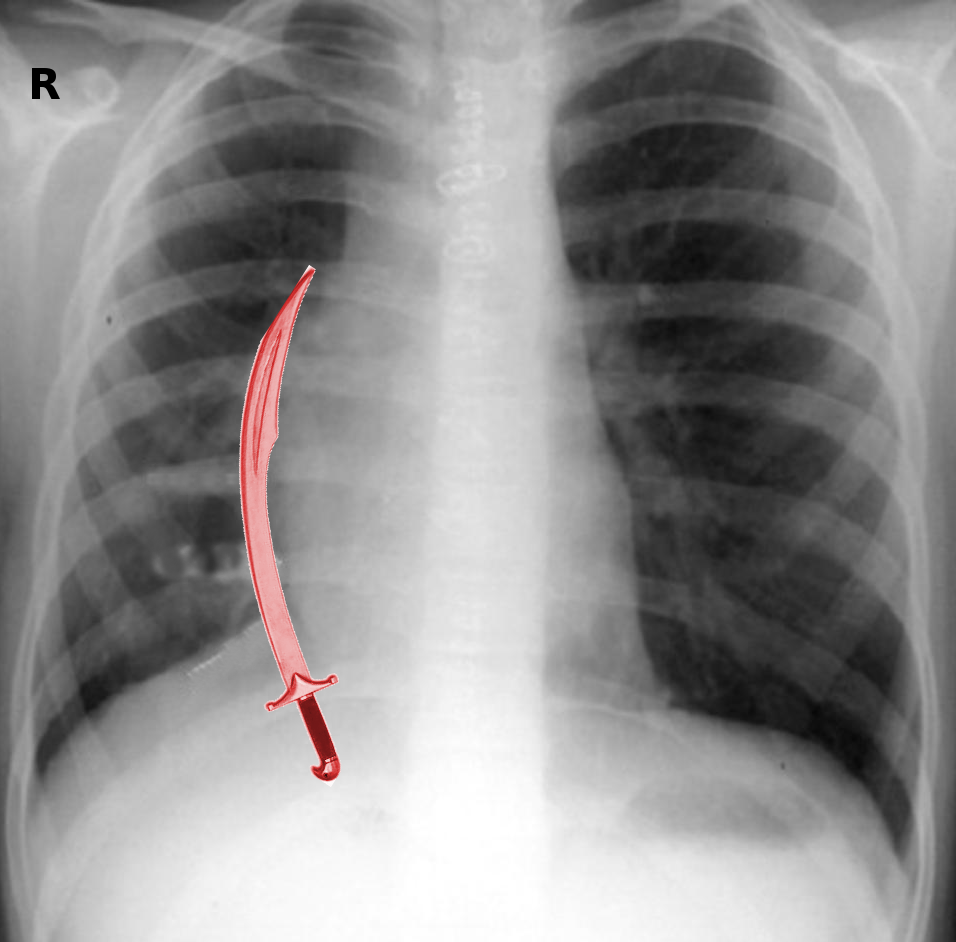

Scimitar syndrome; also known as congenital venolobar syndrome, Halasz syndrome, mirror-image lung syndrome, hypogenetic lung syndrome, and vena cava bronchovascular syndrome, is a rare congenital heart defect. It is a variant of a partial anomalous pulmonary venous return that results in a left-to-right shunt, with a characteristic anatomic feature that resembles a backsword or a saber with a curved blade known as the Middle Eastern or Turkish sword, "scimitar."

The distinct characteristics that constitute scimitar syndrome are:

1) Partial or entire anomalous curved venous drainage of the right lung to the inferior vena cava.

2) Association with variable right lung and pulmonary artery hypoplasia.

3) Dextraposition of the heart.

4) An anomalous systemic blood supply to the ipsilateral lung.

Other associated findings include atrial septal defects and aortopulmonary collaterals. Scimitar syndrome was first described by George Cooper in 1836 while conducting an autopsy of a 10-month-old infant. The first imaging diagnosis was made with cardiac catheterization and described by Dotter et al. in 1949. First surgical intervention performed in 1950 by Drake and Lynch, which involved resection the right lower lung. First corrective surgery in 1956 by Kirklin et al. Schramel et al. with recognition two variations of scimitar veins; a simple classic vein that goes from the middle portion of the right lung running to the cardiophrenic angle and a second type in which a double-arched vein in the lower and upper lung zones drain into the left atrium and inferior vena cava.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact process that contributes to the development of scimitar syndrome is not currently understood, but it is probably attributable to an embryological error of the fundamental development of the lung bud in early embryogenesis.[2]

Epidemiology

There is an estimated incidence of 1 to 3 per 100000 live births, although the true incidence may be higher. It has a female predominance with a female/male ratio of 2 to 1. It presents in 3 to 6% of patients with a partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection.[2][3][4]

History and Physical

Scimitar syndrome has a variable presentation, ranging from an asymptomatic patient with an isolated finding with a benign outcome, to a patient with signs of congestive heart failure and/or respiratory distress. There are two main presentations: infantile and childhood/adult variant; that can divide into three different groups: those associated with other clinically significant cardiac defects, and patients without significant cardiac defects that present either early in infancy or milder forms that present later in childhood/adulthood. The most common associated cardiac defects are atrial septal defect (80%), patent ductus arteriosus (75%), ventricular septal defect (30%) and pulmonary vein stenosis (20%); but you can also find tetralogy of Fallot, aortic arch hypoplasia or coarctation and hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

The infantile form usually correlates with higher comorbidities that include multiple congenital defects (accessory diaphragm, eventration or partial absence of the diaphragm; phrenic cyst; horseshoe lung; and pericardial absence), complicated with severe pulmonary hypertension causing congestive heart failure, contributing to significant mortality. These patients are generally diagnosed within the first few months of life, presenting as failure to thrive, with tachypnea and heart failure, causing a picture of a severely ill and agitated patient with a mortality rate of up to 45%. Patients present with clinical signs of right-to-left shunt if there is pulmonary hypertension, and contributing factors for this development of increased pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratio include:

- Infra diaphragmatic aorta to the lower right lung flow

- Shunts through associated cardiac defects

- Stenosis of the scimitar vein or the pulmonary veins

- Large left-to-right shunts from the scimitar vein

- Pulmonary hypoplasia that leads to increased pulmonary vascular resistance in both lungs

Patients may present with pulmonary infections (especially of the right lower lobe), bronchiectasis and interstitial pulmonary disorders.

The childhood/adult variant tends to be milder with lower mortality rates. Patients present with an incidental finding of an unexplained right heart dilation, as well as frequent pulmonary infections predominant on the right side. Due to mildly elevated pulmonary artery pressure and right-sided volume overload, up to 50% of the patients may experience right ventricular hypertrophy with right bundle branch block. Physical examination characteristically demonstrates a shift of the heart sounds and cardiac impulse to the right, associated with a systolic murmur.[1][2][3][4]

Evaluation

Scimitar syndrome is primarily an imaging diagnosis and gives a characteristic abnormal chest X-ray that shows the shadow of the descending pulmonary vein along the right cardiac border, a hypoplastic lung, as well as dextroposition of the heart. There can be mediastinal shifting in association with atelectasis or pulmonary agenesis.

Echocardiography is a better imaging study to start work-up; it helps to delineate the scimitar vein and any systemic arterial supply to the right lung. Also, identified associated cardiac defects can present in patients with severe symptoms. Fetal echocardiography aid with the prenatal diagnosis by visualization of an obstructed pulmonary venous pathway, confluence behind the right atrium and a vertical vein. The flow velocity pattern that the scimitar vein has is monophasic and extends throughout the cardiac cycle with no reverse flow during atrial contraction different from the normal pulmonary venous flow usually biphasic or triphasic and with reversal of flow during atrial contraction.

Three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) and cardiac-gated magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the best diagnostic modalities, providing an excellent delineation of the anatomy of the abnormal pulmonary vein, its course, connection, and drainage. They can particularly aid with the detection of a horseshoe lung. Cine MRI and 3-D contrast-enhanced MR angiography allow the quantification of the pulmonary venous blood flow and help with the determination of the pulmonary to systemic flow ratio. These imaging modalities will also give a complete anatomical and functional diagnosis preventing the further need for more invasive techniques.

Cardiac catheterization and angiography are the most useful diagnostic studies to confirm the diagnosis of scimitar syndrome but not always necessary. They provide the pulmonary vascular resistance, the degree of the left-to-right shunt, clarification of the exact anatomy with the precise course of the anomalous vein, degree of pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary arterial anatomy, associated cardiac defects and can demonstrate additional systemic arterial collaterals from the thoracoabdominal aorta to the lung.[2][3][5]

Treatment / Management

Scimitar syndrome always needs a multidisciplinary approach. With the infantile form that tends to present with signs of heart failure, medical therapy should be started promptly, allowing the patient to grow until further interventions are needed. A catheter-based approach during angiography consists of obliterating the abnormal systemic arteries from the aorta to the right lung. This will allow for the clinical improvement by reducing the amount of shunt and decreasing the pulmonary arterial pressures. However, this may not work if the patient has associated cardiac defects, requiring early surgical intervention. The childhood/adult form requires surgical intervention with symptomatic patients or when the pulmonary to systemic flow ratio is greater than 1.5 in asymptomatic patients.

The surgical approach to correct scimitar syndrome varies with each case and surgeon preference, depending on the anatomic and pathologic features. Surgical treatment is achievable by either resecting the lung drained by the anomalous scimitar vein or by a corrective method with a re-routing of the flow. Corrective surgical techniques can be performed by either baffling a tunnel or a direct re-implantation to the left atrium of the anomalous pulmonary venous drainage, with or without circulatory arrest. Methods of cardiopulmonary bypass that have been used include: a direct anastomosis of the scimitar vein into the back of the left atrium when the atrial septum is intact, reported by Honey; or 2) division and reimplantation of the anomalous pulmonary vein into the right atrium with baffled flow through an existing or created ASD into the left atrium, proposed by Schumacker and Judd. If stenosis occurs as a complication, dilation with a percutaneous balloon can be performed, with good hemodynamic and symptomatic improvement.

Another approach to redirect the flow from the anomalous pulmonary vein to the left atrium through an ASD is by creating a tunnel with an intra-atrial patch, described by Zubiate and Kay, or by using the free wall of the right atrium, Puig-Massana, and Revuelta. These two surgical procedures require a hypothermic circulatory arrest for appropriate suturing of the intra-atrial baffle. Brown et al. and Lam et al. presented a surgical technique with no baffles or cardiopulmonary bypass by direct re-implantation of the scimitar vein and the left atrium or an interposed tube graft between the scimitar vein and the left atrium respectively. Other techniques that have been used utilize a 14 mm Dacron graft as an extracardiac conduit between the scimitar vein and the left atrium, or as an intra-atrial conduit between the anomalous pulmonary vein and an enlarged ASD. However, the long term patency of the grafts in a venous position is not clear, and some physicians use anticoagulation therapy as an attempt to maximize patency.

Lobectomy or pneumonectomy is only indicated in a patient with recurrent infections, diffuse bronchiectasis, thrombosed intra-atrial baffles, persistent hemoptysis, or marked hypoplasia of the right lung.[2][3][6]

Differential Diagnosis

Other conditions, can simulate the imaging findings, including[2]:

- An abnormal artery associated with hypoplasia of the right lung and aplasia of the pulmonary artery

- An abnormal meandering vein that drains from a hypoplastic right lung to the left atrium

- A bronchopulmonary mass with systemic arterial supply

- Pulmonary sequestration

Prognosis

Historically, the prognosis was grim for the infantile form. Nowadays, with early diagnosis and an established surgical strategy, the outcomes tend to be good with low a low rate of morbidity and mortality after corrective surgery.[2]

Complications

As a general complication, there is a high incidence of postoperative pulmonary venous obstruction and diminished perfusion of the right lung after surgical intervention. The incidence of postoperative complications, mortality, and the need for re-intervention increases with the presence of pulmonary hypertension and associated lesions.[2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should receive information about the therapeutic options available, and the case management approach must be interprofessional so that they have all the information necessary to make informed decisions about their treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Scimitar syndrome is a rare congenital syndrome that requires an interprofessional team approach that includes a pediatrician, pediatric cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, and radiologist. If not diagnosed early, scimitar syndrome can have poor outcomes, especially with the infantile form. An early diagnosis with advance imaging facilitates the surgical strategy, contributing to low morbidity and mortality rates after corrective surgery. There remains a need to define the best surgical option, but longer follow-up is needed.[2]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Wang H, Kalfa D, Rosenbaum MS, Ginns JN, Lewis MJ, Glickstein JS, Bacha EA, Chai PJ. Scimitar Syndrome in Children and Adults: Natural History, Outcomes, and Risk Analysis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2018 Feb:105(2):592-598. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.06.061. Epub 2017 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 29054305]

Ciçek S, Arslan AH, Ugurlucan M, Yildiz Y, Ay S. Scimitar syndrome: the curved Turkish sabre. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. Pediatric cardiac surgery annual. 2014:17(1):56-61. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2014.01.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24725718]

Kahrom M, Kahrom H. Scimitar syndrome and evolution of managements. The Pan African medical journal. 2009 Dec 17:3():20 [PubMed PMID: 21532729]

Abdul Aziz A, Thomas S, Lautner D, Al Awad EH. An Unusual Neonatal Presentation of Scimitar Syndrome. AJP reports. 2018 Apr:8(2):e138-e141. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1656533. Epub 2018 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 29930881]

Masrani A, McWilliams S, Bhalla S, Woodard PK. Anatomical associations and radiological characteristics of Scimitar syndrome on CT and MR. Journal of cardiovascular computed tomography. 2018 Jul-Aug:12(4):286-289. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2018.02.001. Epub 2018 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 29550261]

. Corrigendum to: The natural history and surgical outcome of patients with scimitar syndrome: a multi-centre European study. European heart journal. 2019 Feb 7:40(6):552. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy878. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30590510]