Introduction

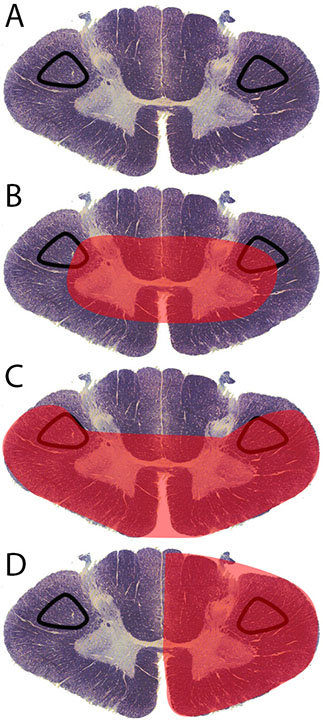

The corticospinal tract controls primary motor activity for the somatic motor system from the neck to the feet. It is the major spinal pathway involved in voluntary movements. The tract begins in the primary motor cortex, where the soma of pyramidal neurons are located within cortical layer V. Axons for these neurons travel in bundles through the internal capsule, cerebral peduncles, and ventral pons. They stay in the ventral position within the medulla as the pyramids. A majority of the axons cross the midline at the pyramidal decussation between the brainstem and spinal cord to form the lateral corticospinal tract (Figure 1A). This crossover causes the left side of the brain to control the right side of the spinal cord and the right side of the brain to control the left side of the spinal cord. A small number of axons remain on the ipsilateral side to form the anterior corticospinal tract. Axons of both anterior and lateral corticospinal tracts move into the gray matter of the ventral horn to synapse onto lower motor neurons. These lower motor neurons exit the spinal cord to contract muscle.[1] While the anterior corticospinal tract assists with axial muscle motor control, the lateral corticospinal tract is the primary pathway for motor information to the body. Injuries to the lateral corticospinal tract results in ipsilateral paralysis (inability to move), paresis (decreased motor strength), and hypertonia (increased tone) for muscles innervated caudal to the level of injury.[2] The lateral corticospinal tract can suffer damage in a variety of ways. The most common types of injury are central cord syndrome, Brown-Sequard syndrome, and anterior spinal cord syndrome.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There are numerous causes for spinal cord injuries: trauma, ischemic events, and disease are the most common methods of damage. Central cord syndrome (Figure 1B) affects the central portion of the spinal cord. It results from hyperextension of the cord, typically within the cervical region. This type of injury is common in shaken baby syndrome. Another cause can be motor vehicle accidents where the head hyper-extends due to contact with the vehicle or air-bag or high impact contact sports such as football.[3]

Anterior spinal cord syndrome is the result of damage or obstruction of the anterior spinal artery (Figure 1C). The spinal cord has one anterior spinal artery and two posterior spinal arteries. The anterior spinal artery supplies the anterior 2/3 of the spinal cord.[4] Thrombosis or an embolism can lead to damage. One of the more common sites of anterior spinal injury is at the artery of Adamkiewcz. This radicular artery branches from the aorta at the level of the 9 to 12 intercostal spaces in most individuals. In a small percentage of people, it originates between L1-L2 or T5-T8.[5] The artery of Adamkiewcz terminates at an acute angle that makes it more prone to damage. Because the artery of Adamkiewcz is prone to damage from surgical procedures that involve the retroperitoneal space, identification and preservation of the artery is important for numerous surgical procedures (e.g., thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair, thoracic or lumbar spine surgery, removal of intramedullary tumors, and retroperitoneal procedures).[6] Other forms of damage that cause anterior spinal cord syndrome include atherosclerotic disease, spinal muscular atrophy, multiple sclerosis, or infections (e.g., West Nile virus, poliomyelitis).[7]

Brown-Sequard syndrome is a condition in which the left or right half of the spinal cord is damaged (Figure 1D). Its typical cause is traumatic injuries such as gunshot and stabbing wounds, motor vehicle accidents, or fractured vertebra due to falls.[7] Other causes for this disorder include vertebral disc herniation, cervical spondylosis, tumors, multiple sclerosis, decompression sickness, cystic disease, as well as infections (e.g., meningitis, tuberculosis, transverse myelitis, and herpes zoster).[8]

Epidemiology

Central cord syndrome (Figure 1B) has a bimodal distribution (young and old age groups), mostly affecting males, and accounts for 9.0% of adult spinal cord injuries and 6.6% of pediatric spinal cord injuries.[3] Central cord syndrome is prevalent among patients with cervical stenosis and the elderly with spinal diseases. However, it is more common in younger patients with cervical spine fractures, disk herniation, or shaken baby syndrome.[9]

Anterior spinal cord syndrome is most common in adults as a result of postoperative complications.[10] It is most prevalent after either retroperitoneal surgeries or spinal surgeries.

Brown-Sequard syndrome is rare, estimated to account for 2 to 4% of spinal cord injuries.[2] Eleven thousand new cases are reported yearly within the United States.[8] Some form of penetrating trauma is the most common cause.

Pathophysiology

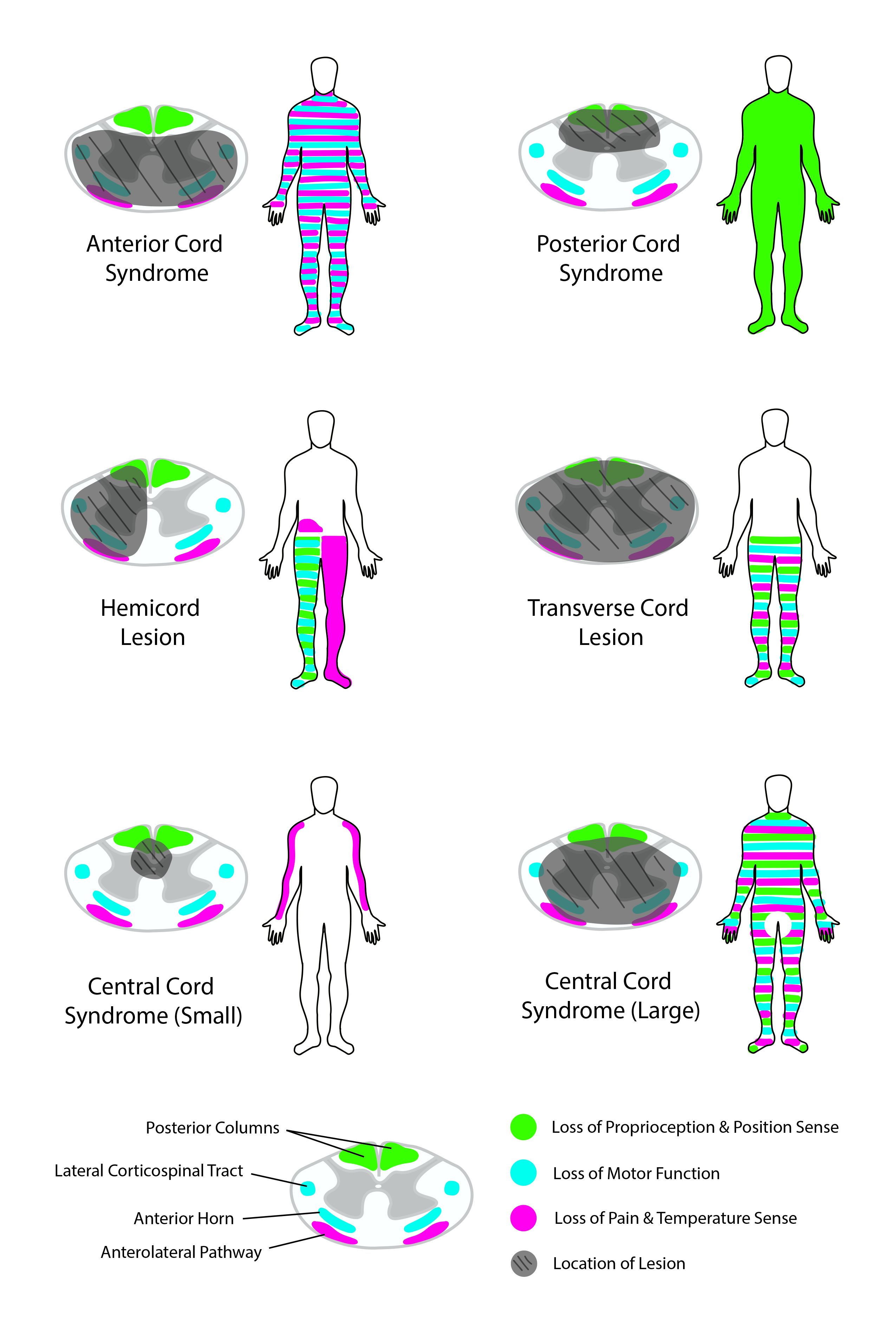

Patients with central cord syndrome have compression of the dorsal column tracts, lateral corticospinal tracts, and spinothalamic tracts. The compression of the dorsal column tracts causes bilateral sensory impairments below the level of injury. Sensory impairment is typically experienced in a “cape-like’ distribution across the upper back and down the posterior side of the upper limbs.[11] Damage to the lateral corticospinal tracts causes bilateral weakness of the upper body, but patients retain strength in the lower limbs.[3] Compression of the spinothalamic tracts results in the bilateral loss of pain/temperature for the upper body more than the lower body. Deficits affecting upper body functions more than the lower body result from compression of the central aspect of the cord. Both corticospinal and spinothalamic tracts have homunculi in which the upper body is located centrally while the lower body is located more peripherally within the spinal cord.[11]

Patients with anterior spinal cord syndrome have bilateral deficits to the corticospinal tracts and spinothalamic tracts. They experience bilateral paralysis and paresis below the site of the lesion.[10] They also experience bilateral pain/temperature and light touch deficits due to the injury of the spinothalamic tract.[12] Sacral sparing of the spinothalamic tract occurs due to a dual blood supply by the posterior spinal arteries. The posterior spinal arteries wrap around the peripheral aspect of the cord. This secondary supply enables the full functionality of the peripheral spinothalamic tract, which transmits pain, temperature, and light touch for the feet.

Patients with Brown-Sequard syndrome have a unilateral deficit of the lateral cord.[8] Deficits associated with this syndrome include ipsilateral paralysis, paresis, and hypertonia; ipsilateral proprioception loss; and contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation.[2][8]

In any of these syndromes, the locus of the injury can cause additional symptoms. If the injury is at or above T1-L2, a compression will disrupt sympathetic neurons within the intermediolateral nucleus in the lateral horn of the spinal cord and cause an ipsilateral Horner syndrome. Similarly, injuries within the lower lumbar region can cause autonomic dysfunction that induces bladder, bowel, or sexual dysfunction.[8][10]

History and Physical

For any spinal cord lesion, the extent of trauma needs to be evaluated. If the injury involves the cervical region, cervical immobilization should be performed during the initial evaluation to prevent additional injury to the cord. An exam should include all primary functions of the spinal cord (i.e., motor, primary touch, proprioception, autonomic function, and pain, temperature, and light touch). Assessment of sensory function for primary touch as well as pain and light touch can be performed by touching a patient at various dermatome regions of the body with a blunt or sharp object. To assess corticospinal tract function, examine muscle tone and spasticity for extensors and flexors of the arms and legs. Test for motor strength and function by having the patient move different groups of muscles with and without resistance — test for proprioception with a finger to nose test, rapid alternating movements test, or Romberg test. If the patient is ambulatory, examine their gate for motor ability and coordination.[13] If the injury occurs in the lower lumbar region, the bowel and bladder can be affected.[8] In these cases, the rectal tone can be assessed to determine the severity of autonomic compromise.

Evaluation

Examination of spinal cord injury caused by trauma should include radiographs to reveal fractures and dislocations of the spine. In addition, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be performed to identify impingement in these cases.[10][11] Impingement in Brown-Sequard syndrome will appear as an “owl’s eye” configuration in the anterior horns.[4] If the anterior spinal syndrome is suspected, a spinal cord angiogram may also be a consideration.[10]

If there is no observable evidence of trauma in the physical exam, a purified protein derivative and sputum for acid-fast bacilli along with a chest X-ray should be performed to ensure that an infectious etiology is not the cause of the symptoms.[8]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of corticospinal lesions involves steroid (methylprednisolone or corticosteroids) administration within the first 8 hours to reduce swelling and pressure on the cord.[11] However, steroids are not recommended for Brown-Sequard syndrome patients because they may make the patient more prone to subsequent infections.[8] If the injury is in the high thoracic or cervical regions, respiratory support may be required, with recommendations for respiratory therapy treatment.[8]

Decompression surgery can be a consideration for patients with a traumatic injury or with a tumor or abscess that causes cord compression.[8][11] After stabilizing the spine, physical rehabilitation is needed to preserve motor activity, muscle strength and to maintain coordination.[10] Wheelchairs, limb supports, and splints can assist the patient with ambulation.[8] Occupational therapy may also be needed to improve and maintain the activity of the upper limbs, specifically in performing daily actions.[10](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for spinal cord syndromes:[8][11]

- Bilateral brachial plexus injuries

- Cysts

- Dislocations

- Epidural abscesses or hematomas

- Fractures

- Infection

- Other spine pathologies and traumas

- Strokes

- The trauma of peripheral nerve roots leading to avulsion in a bilateral distribution

- Tumors

- Vascular injuries

Prognosis

Most patients with central cord syndrome have some recovery of function. Patients who receive treatment soon after the injury have better outcomes. A typical patient will recover in stages. Improvement usually originates in the legs, followed by bladder/bowel, and finally, the arms and hands. Patients with central cord syndrome have a good prognosis but, some factors can put the patient at risk for a lower likelihood of recovery (e.g., advanced age and severity of injury).[3]

The prognosis of patients with Brown-Sequard syndrome depends on the cause and severity of the spinal cord injury. More than half of patients recover and regain motor function.[8] Motor recovery is faster on the contralateral side versus the ipsilateral side.[8] In 90% of cases where bowel and bladder function were affected, patients regain these functions.[8] Recovery typically occurs within 3 to 6 months to two years.[8]

Of the spinal cord syndromes, anterior spinal cord syndrome cases have the worst prognosis. Only 39% of patients recover motor function.[2] Fifty percent of individuals diagnosed with this disorder show no improvement of symptoms over time.[14]

Complications

Complications associated with spinal cord injuries include autonomic dysregulation, neurogenic bladder, and chronic pain.[11] If left untreated, additional symptoms such as hypotension, spinal shock, pulmonary embolism, and infections of the lung or urinary tract can occur.[8]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

In all cases of corticospinal tract lesions, strong recommendations are for physical and occupational therapy. Therapy sessions will help patients regain motor function and adjust to daily life post-injury. Wheelchairs, limb supports, and splints may be utilized to assist the patient to ambulate.[8] Patients and their families will need education on their specific limitations, therapies, and home safety precautions.[10]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients and their families need counseling and education on dysfunctions, deficits, complications, and patient limitations associated with their condition. They need to understand how to manage ambulation and functions of daily living and complications such as neuropathic pain, neurogenic bowel and bladder, and sexual dysfunction.[10] The patient will need to identify strategies on how to return to daily life after injury. Clinicians should also educate the family in specific physical, psychological, and social methods to assist the patient in recovery.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of corticospinal tract lesions are made with an interprofessional team consisting of a neurologist, neurosurgeon, trauma physician, emergency department physician, physical therapist, occupational therapist, and internist.[11] It is crucial to have surgeons involved early on in the case, as surgery can lead to early decompression and stabilization when necessary.[8] After spinal cord stabilization, physical and occupational therapists, nurses, and pharmacists will be instrumental in assisting in long-term recovery that focuses on improving daily life for the patient.[8]

Corticospinal trace lesions require an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and physical and occupational therapists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Welniarz Q, Dusart I, Roze E. The corticospinal tract: Evolution, development, and human disorders. Developmental neurobiology. 2017 Jul:77(7):810-829. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22455. Epub 2016 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 27706924]

Diaz E, Morales H. Spinal Cord Anatomy and Clinical Syndromes. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2016 Oct:37(5):360-71. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2016.05.002. Epub 2016 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 27616310]

Brooks NP. Central Cord Syndrome. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2017 Jan:28(1):41-47. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2016.08.002. Epub 2016 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 27886881]

Harada K, Chiko Y, Toyokawa T. Anterior spinal cord syndrome-"owl's eye sign". Journal of general and family medicine. 2018 Mar:19(2):63-64. doi: 10.1002/jgf2.156. Epub 2018 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 29600133]

Milen MT, Bloom DA, Culligan J, Murasko K. Albert Adamkiewicz (1850-1921)--his artery and its significance for the retroperitoneal surgeon. World journal of urology. 1999 Jun:17(3):168-70 [PubMed PMID: 10418091]

Charles YP, Barbe B, Beaujeux R, Boujan F, Steib JP. Relevance of the anatomical location of the Adamkiewicz artery in spine surgery. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2011 Jan:33(1):3-9. doi: 10.1007/s00276-010-0654-0. Epub 2010 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 20589376]

Lindeire S, Hauser JM. Anatomy, Back, Artery Of Adamkiewicz. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422566]

Shams S, Arain A. Brown-Sequard Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30844162]

Ghatan S, Ellenbogen RG. Pediatric spine and spinal cord injury after inflicted trauma. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2002 Apr:13(2):227-33 [PubMed PMID: 12391706]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKlakeel M, Thompson J, Srinivasan R, McDonald F. Anterior spinal cord syndrome of unknown etiology. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2015 Jan:28(1):85-7 [PubMed PMID: 25552812]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmeer MA, Tessler J, Munakomi S, Gillis CC. Central Cord Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722961]

Imbert B, Brion JP, Janbon B, Gonzales M, Micoud M. [Erythema nodosum associated with parvovirus B19 infection]. Presse medicale (Paris, France : 1983). 1989 Oct 28:18(35):1753-4 [PubMed PMID: 2555812]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDavenport D, Colaco HB, Kavarthapu V. Examination of the adult spine. British journal of hospital medicine (London, England : 2005). 2015 Dec:76(12):C182-5. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2015.76.12.C182. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26646344]

Schneider GS. Anterior spinal cord syndrome after initiation of treatment with atenolol. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2010 Jun:38(5):e49-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.08.061. Epub 2008 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 18597977]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence