Introduction

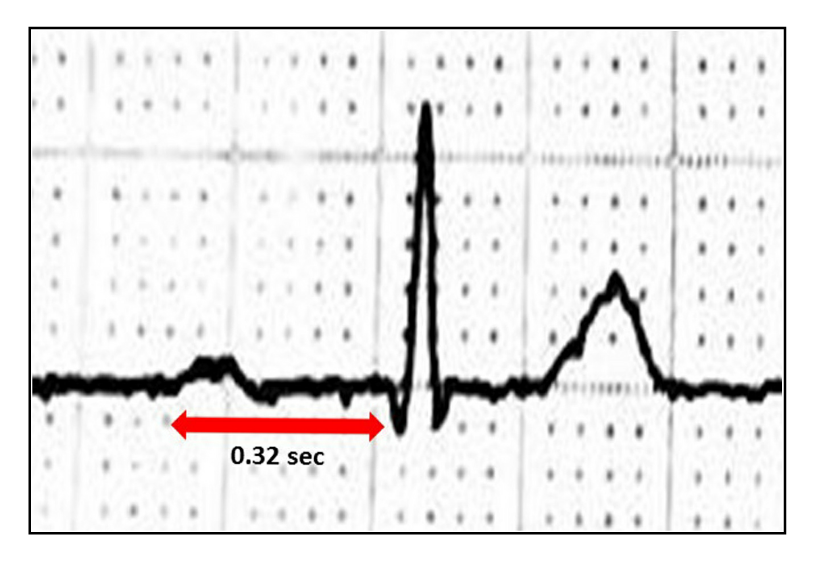

The definition of first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block is a PR interval of greater than 0.20 seconds on electrocardiograph (ECG) without disruption of atrial to ventricular conduction (see Image. First-Degree AV Block, Electrocardiograph). The normal measurement of the PR interval is 0.12 seconds to 0.20 seconds. When the PR interval prolongs more than 0.30 seconds, the first-degree atrioventricular block is called "marked." In certain situations, the P waves can be within the preceding T waves. It is generally asymptomatic and without significant complications. For the vast majority of patients, no treatment is necessary beyond routine observation for worsening conduction delay. Regular evaluation is essential, as affected patients have demonstrated an increased risk of developing atrial fibrillation or a higher degree of AV block.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Researchers have attributed first-degree AV bloc to increased vagal tone in younger patients, as many of the early population studies of the condition utilized young, healthy volunteers. Fibrotic changes in the cardiac conduction system appear to be one of the common etiologies in elderly patients. Additionally, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, electrolyte abnormalities (particularly hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia), inflammation, infections (endocarditis, rheumatic fever, Chagas disease, Lyme disease, diphtheria) drugs (antiarrhythmics Ia, Ic, II, III, IV and digoxin), infiltrative diseases (sarcoidosis), collagen vascular diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and scleroderma), idiopathic degenerative diseases (Lenegre and Lev diseases) and neuromuscular disorders are identifiable causes of first-degree AV block.[3][4]

Epidemiology

Prevalence increases with age, with most studies finding a prevalence of 1.0% to 1.5% until age 60, at which point the prevalence rises to approximately 6.0%. It is more common in males, with an approximate 2 to 1 ratio of males to females. Prevalence rates above 10% have been observed in populations of young athletes, suggesting that increased parasympathetic autonomic tone plays a role in the development of first-degree AV block in younger patients.[5][6]

Pathophysiology

Electrophysiological studies have shown that PR interval prolongation could be due to conduction delay located at the atrioventricular node, right atrium, or the His Purkinje system. However, the most commonly affected place is the AV node. The morphology and size of the QRS complex reflect that the His Purkinje system is the site of conduction delay. The presence of first-degree AV block on ECG represents prolonged conduction in the AV node, commonly due to increased vagal tone in younger patients and fibrosis of the conduction system in older patients.[7]

Even though conduction slows, every impulse originating from the atrium is passed to the ventricles. The conduction delay may also be due to dysfunction in the atria, at the bundle of His, or in the Purkinje system. Delayed conduction in these areas is more often due to underlying heart disease and more frequently progresses to a higher degree of AV blockade. Patients with conduction abnormalities originating in the His or Purkinje systems are more likely to have prolonged QRS intervals as well as the prolonged PR interval of first-degree AV block. Prolonged conduction is well-tolerated, especially when the PR interval remains shorter than 0.30 seconds. As the PR interval extends beyond 0.30 seconds, synchrony of atrial and ventricular systole worsens, potentially resulting in poor ventricular preload and symptoms of the “pacemaker syndrome,” further characterized below.[8] Poor ventricular filling due to prolonged PR intervals may also result in mitral regurgitation, which exacerbates conditions such as heart failure.

History and Physical

First-degree AV block is almost universally without associated symptoms. Patients will frequently be unaware of the condition until it appears on routine electrocardiography. Upon recognition of the PR interval prolongation, a thorough history should be obtained, with a specific focus on any history of congenital or acquired heart disease, risk factors for heart disease, family history of cardiac disease, the presence of neuromuscular disease, or family history of neuromuscular disease. In higher-grade first-degree block (PR interval greater than 0.30 seconds), patients may develop symptoms similar to pacemaker syndrome: dyspnea, malaise, lightheadedness, chest pain, or even syncope due to poor synchronization of atrial and ventricular contractions.[8] With the delay in ventricular contraction, patients will experience discomfort as the atria contract against closed atrioventricular valves. Similarly, the physical exam will typically be normal, and there are no common physical exam findings suggestive of first-degree AV block. It is sensible to conduct a general assessment for signs of cardiac diseases, such as auscultation for murmurs or additional heart sounds, palpation for JVD and peripheral edema, and a skin evaluation for cyanosis, clubbing, or other signs of chronic cardiac disease.

Evaluation

A PR interval of greater than 0.20 seconds on a surface ECG, without associated disruption of atrial to ventricular conduction, is diagnostic of first-degree AV block. When the clinician identifies this on ECG, they should query patients about the presence of pre-existing heart disease (acquired or congenital) and family history of heart disease. Patients with heart disease or with a family history of heart disease warrant investigation for organic causes of the PR interval prolongation.[9] In otherwise asymptomatic patients, further diagnostic evaluation may not be necessary. In symptomatic patients, those with associated prolongation of the QRS interval, and those with associated heart disease, referral for more invasive electrophysiologic studies may be indicated, which will help identify the location of the conduction delay.[1]

Treatment / Management

For the majority of patients with first-degree AV block, there is no need for treatment. The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines do not recommend permanent pacemaker placement for patients with first-degree AV block, with the exception of patients with PR interval greater than 0.30 seconds who are experiencing symptoms believed to be due to the AV block.[10] These symptoms are similar to those noted above and are frequently due to asynchrony of the atria and ventricles. Additionally, patients with first-degree AV block and coexisting neuromuscular disease or a prolonged QRS interval may also be candidates for pacemaker placement.(A1)

In patients with AV block related to myocardial infarction, pacemaker placement may be indicated, but is often delayed to determine if the AV block is transient as the patient recovers from the myocardial infarction. There is no indication for antiarrhythmic medication for first-degree AV block. In the absence of symptoms, patients do not require treatment beyond surveillance to assess for worsening AV block. This surveillance may be done with routine ECGs, and further investigation is rarely indicated if there is no worsening of the PR interval prolongation. Although generally believed to be a benign condition, cohort studies have shown that patients with first-degree AV block have a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation, pacemaker placement, and all-cause mortality than patients with normal PR intervals. At this time it is unknown if this is because first-degree AV block is more common in patients with organic heart disease or if first-degree AV block is a pathologic condition, prone to progress to higher-grade blocks, even in the absence of concomitant heart disease.[9][11][12](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for first-degree heart block includes the following:

- Atrioventricular block

- Atrioventricular dissociation

- Second-degree AV block

- Third-Degree AV block

Prognosis

Isolated first-degree heart block was initially thought to have a benign prognosis, as it has no direct clinical consequences. Patients with this condition demonstrate no direct symptomatology. The Framingham Study revealed that patients with prolonged PR intervals or first-degree heart block had twice the risk of developing atrial fibrillation and were three times more likely to require a pacemaker.[7]

Complications

While first-degree heart block is usually asymptomatic and an incidental ECG finding, patients should have routine follow-up monitoring to ensure the condition does not progress to worse cardiac conduction issues. Patients can generally lead a normal, symptom-free life absent any progression of the condition.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients often require no treatment first first-degree heart block. They should receive counseling on symptoms associated with worsening heart block, such as:

- Dizziness or fainting

- The feeling of a "missed" beat

- Chest pain

- Dyspnea or shortness of breath

- Unexplained nausea

- Easily fatigued

Pearls and Other Issues

First-degree AV block is generally asymptomatic and therefore well-tolerated. Studies show that as patients with this condition age, they become more likely to develop associated rhythm disturbances such as atrial fibrillation or high-degree AV blocks. Therefore, close observation of patients with known first-degree AV block is indicated as they advance in age or if they develop coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular disease, or another potentially complicating condition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

First-degree heart block is often an incidental finding on the ECG. The majority of patients may have no symptoms. Because these patients may present to almost any medical or surgical specialty, an understanding and management of this benign heart disorder is necessary for all healthcare workers. The prognosis for patients with first-degree heart block is excellent. Progression to a second-degree heart block is very rare. For those who have acquired Lyme-induced heart block, the condition usually resolves spontaneously in 2 to 10 days. While first-degree heart block has always been considered to be a benign disorder, epidemiological data from the Framingham study suggest that it may be associated with atrial arrhythmias, need for pacemaker implantation, and all-cause mortality.[7] The condition does not appear to be benign in the presence of a depressed ejection fraction, heart failure, or systolic dysfunction. When the condition is diagnosed by a primary care provider or nurse practitioner, an appropriate referral should be made to a cardiologist who can determine the extent and/or need for further workup.[1][3]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Lewalter T, Pürerfellner H, Ungar A, Rieger G, Mangoni L, Duru F, INSIGHT XT study investigators. "First-degree AV block-a benign entity?" Insertable cardiac monitor in patients with 1st-degree AV block reveals presence or progression to higher grade block or bradycardia requiring pacemaker implant. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2018 Aug:52(3):303-306. doi: 10.1007/s10840-018-0439-7. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30105427]

Lee S, Singla M. An Unrecognized Rash Progressing to Lyme Carditis: Important Features and Recommendations Regarding Lyme Disease. American journal of therapeutics. 2016 Mar-Apr:23(2):e566-9. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000217. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25730155]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNikolaidou T, Ghosh JM, Clark AL. Outcomes Related to First-Degree Atrioventricular Block and Therapeutic Implications in Patients With Heart Failure. JACC. Clinical electrophysiology. 2016 Apr:2(2):181-192. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2016.02.012. Epub 2016 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 29766868]

van Stigt AH,Overduin RJ,Staats LC,Loen V,van der Heyden MA, A Heart too Drunk to Drive; AV Block following Acute Alcohol Intoxication. The Chinese journal of physiology. 2016 Feb 29 [PubMed PMID: 26875557]

Rojas LZ, Glisic M, Pletsch-Borba L, Echeverría LE, Bramer WM, Bano A, Stringa N, Zaciragic A, Kraja B, Asllanaj E, Chowdhury R, Morillo CA, Rueda-Ochoa OL, Franco OH, Muka T. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in Chagas disease in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2018 Jun:12(6):e0006567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006567. Epub 2018 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 29897909]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMantovani A, Rigolon R, Pichiri I, Morani G, Bonapace S, Dugo C, Zoppini G, Bonora E, Targher G. Relation of elevated serum uric acid levels to first-degree heart block and other cardiac conduction defects in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes. Journal of diabetes and its complications. 2017 Dec:31(12):1691-1697. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.09.011. Epub 2017 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 29033310]

Cheng S, Keyes MJ, Larson MG, McCabe EL, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Vasan RS, Wang TJ. Long-term outcomes in individuals with prolonged PR interval or first-degree atrioventricular block. JAMA. 2009 Jun 24:301(24):2571-7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.888. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19549974]

Barold SS. Indications for permanent cardiac pacing in first-degree AV block: class I, II, or III? Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : PACE. 1996 May:19(5):747-51 [PubMed PMID: 8734740]

Holmqvist F, Daubert JP. First-degree AV block-an entirely benign finding or a potentially curable cause of cardiac disease? Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology : the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc. 2013 May:18(3):215-24. doi: 10.1111/anec.12062. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23714079]

Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, DiMarco JP, Dunbar SB, Estes NA 3rd, Ferguson TB Jr, Hammill SC, Karasik PE, Link MS, Marine JE, Schoenfeld MH, Shanker AJ, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Stevenson WG, Varosy PD, Ellenbogen KA, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hayes DL, Page RL, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO, American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, Heart Rhythm Society. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update of the 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. [corrected]. Circulation. 2012 Oct 2:126(14):1784-800. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182618569. Epub 2012 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 22965336]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceClowse MEB, Eudy AM, Kiernan E, Williams MR, Bermas B, Chakravarty E, Sammaritano LR, Chambers CD, Buyon J. The prevention, screening and treatment of congenital heart block from neonatal lupus: a survey of provider practices. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2018 Jul 1:57(suppl_5):v9-v17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key141. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30137589]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGeorgijević L, Andrić L. Electrocardiography in pre-participation screening and current guidelines for participation in competitive sports. Srpski arhiv za celokupno lekarstvo. 2016 Jan-Feb:144(1-2):104-10 [PubMed PMID: 27276869]