Introduction

Lumbosacral spondylolisthesis is the forward translation of the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) over the first sacral vertebra (S1). Bilateral L5 pars defect (spondylolysis) or repetitive stress injury is the primary etiology behind lumbosacral spondylolisthesis. The degree of a slip often correlates with the degree of symptoms.

The prevalence of spondylolysis (pars defect), in the general population, is 6%, and a third of those will subsequently develop a degree of spondylolisthesis.[1] The majority of cases are mild or asymptomatic, and only a relatively small percentage of symptomatic patients require surgical intervention.

The most commonly affected populations are children and adolescents participating in sports that require repetitive lower back hyperextension (divers, pace cricket bowlers, baseball, softball, rugby, weightlifting, sailing, table tennis, wrestlers, gymnasts, dancers, and footballers). They usually present with lower back pain exacerbated by activity.[2] Occasionally pain can radiate to both buttocks and legs, and in advanced cases, the gait pattern and walking distance may be affected. Presentation in adults is more insidious and commonly associated with long-standing degenerative changes secondary to the slip, often leading to spinal canal stenosis and radicular pain.

Management of the majority of the cases is non-operative, but patients who fail non-operative treatment and continue having disabling symptoms may require surgical treatment.[2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A Wiltse-Newman classification describes different etiology of pars interarticularis failure [4]:

- Type I Dysplastic – congenital defect in pars

- Type II (isthmic) is the most common

- II A pars fatigue fracture

- II B pars elongation due to multiple healed stress fractures

- II C pars acute fracture

- Type III degenerative spondylolisthesis from degenerative facet instability without pars fracture

- Type IV Traumatic – due to acute posterior arch fracture other than pars

- Type V Neoplastic – pathologic destruction of the pars

Depending on the degree of the forward slip, the severity of this process is graded as mild, severe, or complete slip (spondyloptosis) - described later in Myerding classification.

In the most common isthmic spondylolisthesis, which leads to an L5/S1 slip, the following stages have been identified.

- Pars stress reaction (sclerosis with incomplete bone disruption/fracture)

- Spondylolysis (anatomic defect in the pars, radiolucent gap with adjacent bone sclerosis, without any translation of the vertebra)

- Spondylolisthesis (due to bilateral pars defect, forward translation of the superior vertebra over the inferior one)

The second most common types of spondylolisthesis are type I (dysplastic) and III (degenerative). Degenerative spondylolisthesis is most prevalent in the adult population, and levels affected most frequently are L4/L5 followed by L3/L4. Due to the chronicity of the instability, often associated degenerative changes in the intervertebral disc and facet joints occur. They often lead to secondary hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and subsequent spinal canal stenosis. This condition usually presents with bilateral buttock pain and neurogenic claudication (back pain eased by sitting down/leaning forward).

Epidemiology

Estimates are that 4 to 6% of the population has a degree of lumbosacral spondylolisthesis. The majority of cases are asymptomatic.[5]

Most of the symptomatic high-grade slips occur in the pediatric/adolescent population participating in sports involving repetitive hyperextension, while adults tend to present with milder and more chronic onset of symptoms.[6]

The most commonly affected adolescent groups are female dancers or gymnasts with hyperlordosis and hyper flexibility, male football players, or weight lifters with limited motion at lumbar spine undergoing a growth spurt, or novice athletes vigorously training while having poor core strength.[7]

There are reports of familial association and congenital abnormalities, including spina bifida occulta, thoracic hyperkyphosis (Shauerman disease) as predisposing factors as well as general ligamentous laxity.

Several anatomical factors described below predispose to spondylolisthesis.

Pathophysiology

Two mechanisms may cause the lytic defect. The first is the pincer effect due to repeated hyperextension.[8] The inferior facet of L4 and the superior facet of S1 creates a pincer effect on the pars interarticularis, causing a failure of the L5 pars. This condition is more likely to occur in a situation where the sacral slope has a low value with a more horizontally orientated superior sacral endplate. The second mechanism is when there is an increased sacral slope and hence increased traction on the pars interarticularis.[9] The repeated traction on the pars from a downsloping lumbosacral junction results in failure and fracture of the pars interarticularis. In high-grade slips, the anterosuperior part of the sacrum becomes dome-shaped, which may be due to repeated trauma to the anterosuperior apophyseal ring of the S1 vertebrae.[10]

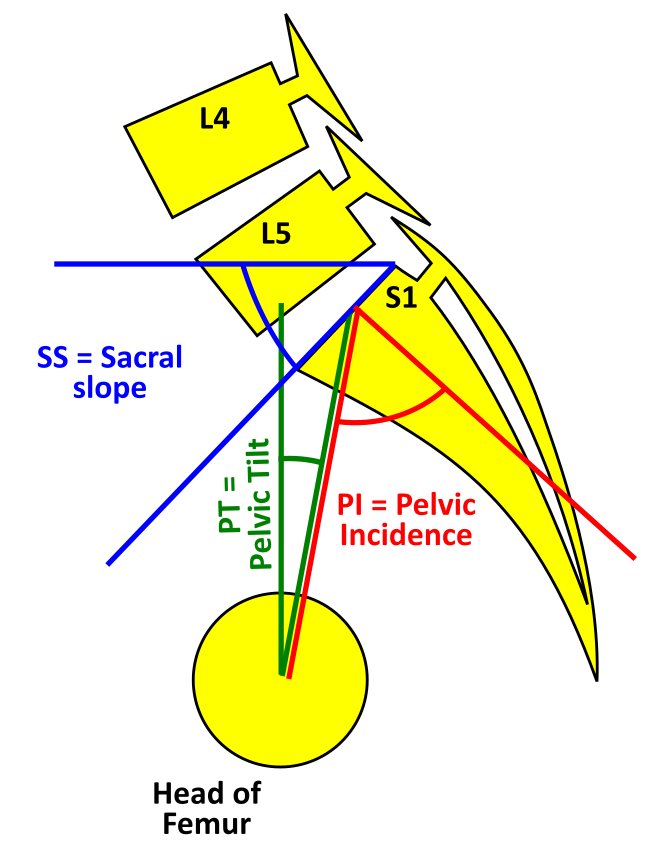

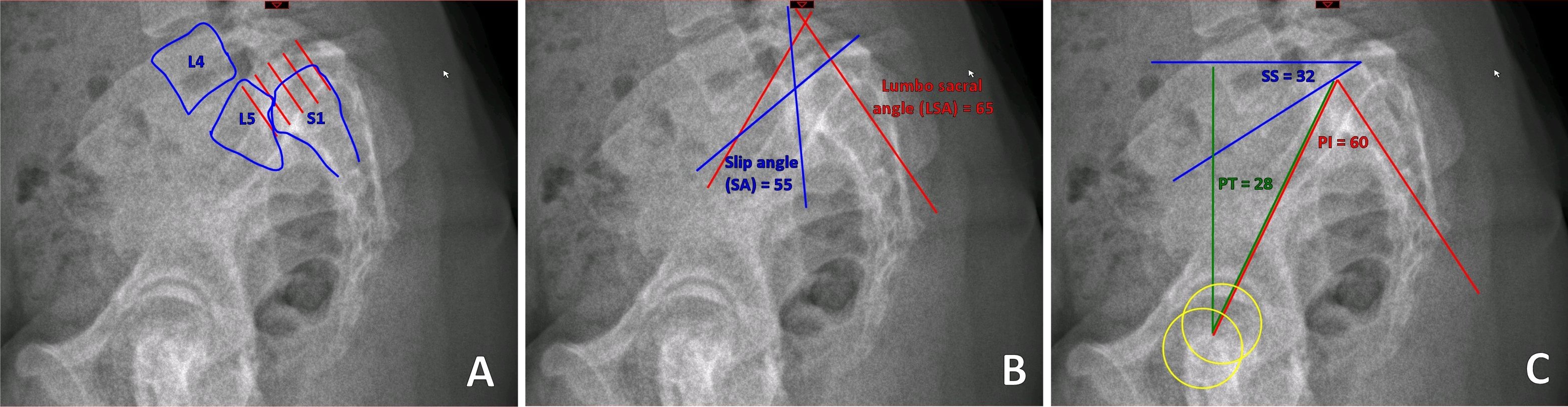

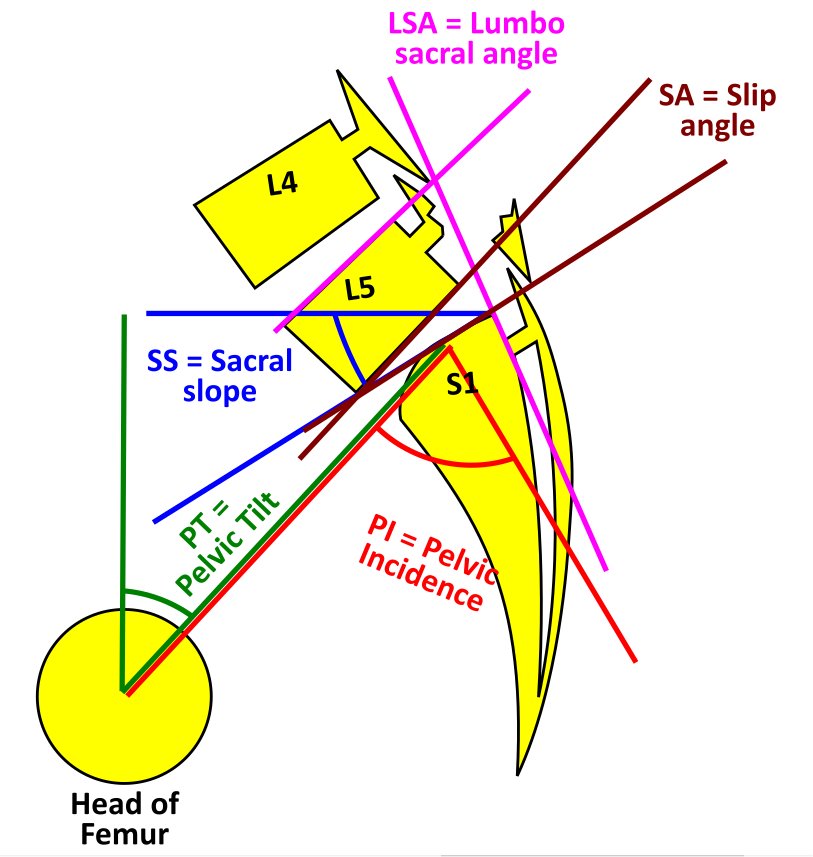

The spinopelvic balance and the global spinal alignment are essential in understanding the etiology, grading, and planning the treatment protocol.[11] These parameters are measured on a standing lateral radiograph. The main parameters and their definitions are as follows.

- Pelvic Tilt (PT) is the angle measured between a line drawn from the center of the superior endplate of S1 to the center of rotation of the femoral head and the vertical reference line.[11]

- Sacral Slope (SS) is the angle between the line drawn along the superior end of the S1 endplate and the horizontal reference line.[11] The pelvic tilt (PT) and the sacral slope are referenced to the vertical and horizontal planes and hence can vary based on the position of the pelvis. Though the standard measurements are on a standing radiograph, the values of PT and SS alter between sitting and standing.

- The Pelvic Incidence (PI) is the angle between a line starting at the midline between centers of rotation of each femoral head drawn towards the midpoint of S1 superior endplate and a line perpendicular to the line drawn along the superior endplate of S1.[10] The normal value is 50 degrees. An increased Pelvic Incidence (PI) is associated with higher severity of slips.[12] In comparison to the PT and SS, the Pelvic Incidence is a fixed value and does not change with the position of the pelvis or in adult life. A value of 70 to 80 degrees presents in patients with significant spondylolisthesis. Pelvic Incidence = Pelvic Tilt + Sacral Slope

- Boxall’s Slip Angle and Dubosset’s lumbosacral angle measures the relationship between L5 and S1.[13][14] The Boxalls slip angle is measured between the perpendicular to the posterior aspect of the S1 vertebrae and the lower border of L5. If slip angle measures >45 degrees, it is associated with a greater risk of slip progression, instability, and post-op pseudo-arthrosis. It predicts intervention and affects cosmesis as well as prognosis.[11] The Dubosset’s lumbosacral angle is measured between the posterior aspect of the S1 and the upper endplate of the L5. Unlike the slip angle, the lumbosacral angle does not involve surfaces that alter with dysplasia.

Forward translation of the vertebrae may cause a narrowing of the spinal canal at the level of the slip. This situation is rare as most of the slips are only grade I or II, but the secondary canal and foraminal stenosis can occur due to subsequent degenerative changes in facet joints, hypertrophy of ligamentum flavum, hypertrophic fibrous repair tissue of the pars defect, or bulging of L5/S1 disc. In severe L5/S1 slips, the L5 nerve root is most commonly affected by being pulled forward by the superior vertebra.

History and Physical

Most cases of spondylolisthesis are asymptomatic.

Severe slips are uncommon, and deformity rarely progresses beyond Meyerding grade II (see Evaluation chapter).

Typical history and examination findings in symptomatic cases involve:

History

- Child participating in back hyperextension activities (gymnastics, football, weight lifting), most common age at presentation is 4 to 6 yrs old.

- In adults insidious onset of axial back pain exacerbated by physical activity, periodic exacerbations that vary in intensity and duration

- L5 radicular symptoms (in severe slips), including weakness of the extensor hallucis longus

- Bladder and bowel dysfunction (including cauda equina syndrome in extreme cases)

- Neurologic claudication secondary to spinal canal stenosis (buttock and leg pain worse with walking but improving with leaning forward or sitting)

Examination Findings

- Pain with back hyperextension. Hyperextending the lower back while standing on one leg is termed the "stork test."

- Limitation of lumbar spine flexion and extension

- Increased popliteal angle

- Gait alteration with abductors weakness (L5) (pelvic waddle)

- Flattened lumbar lordosis or kyphosis of the lumbosacral junction

- Palpable step-off of the spinous process

- Hamstring tightness (in extreme cases walking with hips and knees flexed- due to vertical orientation of the sacrum causing pelvic retroversion and compensatory lumbar hyperlordosis + shortened stride and lurched posture)

- "Heart-shaped" buttocks in severe cases of significant lumbosacral kyphosis and sacral retroversion (sacrum becoming more vertical in orientation and moving away from the head of the femurs).

- Straight leg raise test may be positive.

- Scoliosis may be present - this may be secondary to pain.

Listhetic crisis (rapid progression of symptoms). Common during a growth spurt or increased physical activities with bilateral pars failure.

- Severe back pain aggravated by extension and relieved by rest.

- Neurologic deficit

- Hamstring spasm - walk with a crouched gait

Evaluation

Following the history and examination, the best screening tool is an AP and lateral weight-bearing X-ray of the lumbar spine.[15] Lumbosacral spondylolisthesis can be best assessed mainly on the lateral view, but occasional coronal deformity should not be missed. In cases where clinical examination indicates an abnormal sagittal balance of the spinal column, a whole spine lateral standing X-ray is indicated. In the majority of cases, an isthmic defect will be detected on radiographs but in doubtful cases. An MRI scan is recommended. Oblique X-rays of the lumbosacral junction, Computerised Tomography (CT) scan, SPECT scans may also identify the defect but involve ionic radiation.

MRI scans are more sensitive in identifying pars lesions.MRI can also identify stress reactions that occur even before a fracture line develops.[16] In dysplastic cases, dome-shaped or significantly inclined sacrum can present as well as trapezoid-shaped L5 and dysplastic facets of S1. Neoplasms and infections are an extremely rare primary cause of spondylolisthesis but should merit consideration as a differential diagnosis in patients with constitutional symptoms. To assess dynamic instability, flexion and extension views should be obtained. Either 4 mm of translation or 10 degrees of angulation of motion compared to the adjacent motion segment are diagnostic for spondylolisthesis.

Grading of the forward slip is classified by Meyerding classification:

- Grade I <25% of the width of the vertebra on the lateral view

- Grade II 25 to 50%

- Grade III 50 to 75%

- Grade IV 75 to 100%

- Grade V >100% (spondyloptosis)

Pelvic incidence (PI) has a direct correlation to Meyerding's grade.[12]

The Spinal Deformity Study Group has created a new classification that guides treatment. This scale takes into account the spinopelvic parameters and the overall spinal alignment.[17]

- I < 50% slip, PI <45 degrees, Surgery only if symptoms not controlled by non-operative methods.

- II < 50% slip, PI 45 to 60, Surgery only if symptoms not controlled by non-operative methods.

- III < 50% slip, PI >60 degrees, posterolateral fusion can be considered

- IV >50% slip, balanced pelvis high SS / low PT, decompression + / - Posterolateral fusion may be adequate

- V >50% slip, Unbalanced pelvis (retroverted) Low SS / High PT, reduction of slip, and circumferential fusion may be a consideration.

- VI >50% slip, Unbalanced spine (retroverted pelvis) Low SS / High PT + C7 plumbline anterior to femoral heads reduction of slip and circumferential fusion may be considered.

MRI (T-2 weighted sequence is best to assess spinal canal stenosis, foraminal stenosis, and nerve root impingement, as well as the morphology of lumbar and sacral vertebrae which presence correlated with history and examination findings, will dictate the surgical management). The most commonly affected nerve root is L5.

Treatment / Management

The majority of the cases can be treated non-operatively by:

- Thoracolumbosacral / lumbosacral brace.[18] In acute cases in the adolescent sportsperson bracing to prevent extension is shown to be superior to just activity modification.

- Activity modification (avoidance of hyperextension)[19]

- Core muscles strengthening focusing on the deep abdominal muscles and the multifidus muscle[20]

- Lumbar flexion-based exercises.[21]

- Analgesia

- In cases of adult degenerative spondylolisthesis with canal stenosis, an epidural steroid injection can provide short-term relief.[22] (A1)

Non-operative management of acute cases among sportspersons was successful in 95% of patients, and only 5% required surgical intervention. Among that treated non-operatively, 82% returned to their previous level of play.[19] Approximately one-third of patients with spondylolisthesis experience a disease progression over time. Operative treatment is reserved for those with intractable pain or neurological symptoms, including claudication or radiculopathy.[23]

Surgical intervention has shown >80% success in appropriately selected patients, with a low incidence of complications. Surgical techniques include the following:

- In the pediatric population with pars fracture or non-union, surgical repair of the pars may be an option with lag screw or tension band wire technique or pedicle screw hook fixation.[24][25]

- Uninstrumented fusion in situ, A randomized control trial by Moller [26] showed that there was no advantage in adding instrumentation. Pain, functional disability, and fusion rates were similar in both groups.

- Decompression, Though there was some skepticism in just performing decompression of the nerve roots without fusion, i.e Gills procedure, results show 70 % good results with regards to patient satisfaction. Only grade I and II patients met the inclusion criteria for the study.[27]

- Instrumented posterolateral fusion with decompression is the standard procedure.[26]

- Anterior / posterior / transforaminal and direct lateral lumbosacral interbody fusion, reduction, and fusion.[28] The anterior, posterior, transforaminal, and direct lateral indicate the path through which the interbody device or cage is inserted. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) involves the insertion of the cage between the vertebral bodies medial to facets. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) requires facetectomy and a more lateralized and transforaminal approach to the disc space. Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (ALIF) is via a trans or retroperitoneal approach and offers better access to disc space and endplate. They can also be associated with retrograde ejaculation and sexual dysfunction. Direct lateral or the transpsoas approach can only access the disc spaces above the L5 vertebrae. The iliac crest is in the path of reaching the L5/S1 disc on the direct lateral approach.[29]

- Reduction with spondylolectomy (vertebrectomy) of L5 and fusion of L4 on S1.[30] In severe slips removing the L5 vertebrae allows reduction and better spinal alignment

- Sacral dome resection and fusion.[31] (A1)

Operative options should be considered only if non-operative options fail or symptoms are significant. The reduction of the slip is controversial as in approximately 20% of cases, it causes L5 nerve root injury. Nevertheless, some evidence suggests better functional and cosmetic outcomes for patients who underwent reduction and instrumented fusion.[32] Foraminal decompression may also be necessary. Interbody fusion with the maintenance of intervertebral space improves the foraminal height, helps restore lumbar lordosis, and avoids fusion to L4 in high-grade slips. Each case requires an individual approach, and factors like the degree of spondylolisthesis, predominant neurological symptoms, and patients comorbidities should be taken into consideration.[33] Minimally invasive surgical techniques are gaining in popularity.[34](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

- Mechanical or muscular back pain

- Disc degeneration, facet joint osteoarthritis (OA), and/or cyst

- Lumbar canal stenosis secondary to degenerative changes

- Neoplastic process/metastases

- Infection (discitis, TB, paraspinal abscess)

- Vascular claudication (improves at rest in a standing position while neurological claudication improves with lumbar spine flexion - leaning forward or sitting)

Prognosis

Despite the estimate of up to 6% of the population suffering from spondylolisthesis, the majority of them are asymptomatic. Only a small percentage of symptomatic cases will require surgical treatment.

Worst prognosis in cases of:

- Very young age at presentation

- Female

- Slip angle >45 degrees

- High-grade slip

- Degenerative slip (most commonly in adults)

Complications

- The most common reported neurological complication after lumbosacral spondylolisthesis surgery is L5 nerve root dysfunction. It is most frequently associated with high-grade slips and attempts of slip reduction as well as foraminal stenosis decompression. L5 nerve root dysfunction is usually transient and resolves within a few months in the postoperative period. In their cadaveric study, Petraco et al. found out that 71% of total nerve strain occurs during the second half of the reduction.[35]

- Pseudoarthrosis

- Dural tear

- Adjacent segment disease (2 to 3%)

- Surgical site infection (0.1 to 2%)

- Positioning neuropathy: Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve - from a prone position with iliac bolster, ulnar nerve, or brachial plexopathy with inappropriate arm position)[36]

Complication rate increases with age, increased intraoperative blood loss, longer operative time, the number of levels fused.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Sports coaches and personal trainers working with children and adolescents especially those practicing gymnastics, football, or weight lifting, should be aware of the symptoms of spondylosis and spondylolisthesis. They should be able to identify cases when pain does not improve after rest and basic stretching and strengthening exercises. These sportspersons need to be referred for specialist evaluation to diagnose and treat. This is particularly important as braces that prevent extension and activity reduction have shown excellent results.

Affected patients should be educated about the importance of activity modifications and physiotherapy and engage with core muscle strengthening and flexion exercises for symptomatic treatment.

They should receive reassurance that most of the symptoms are transient. But at the same time, especially those with a high risk of slip progression should be followed up by a specialist Orthopedic surgeon and educated about symptoms and signs of slip progression and potentially serious complications like cauda equina syndrome.

Pearls and Other Issues

Pars interarticularis defects were common in sportsperson involved in increased activity. Hyperextension of the spine during the sport was a risk factor. In cricket fast bowlers extended and laterally flexed their spine, before throwing the ball to increase the speed of delivery. This repetitive movement increased the likelihood of developing a pars defect. In a recent review pars interarticularis defects were more common in the following sports, diving (35.38%), cricket (31.97%), baseball/softball (26.91%), rugby (22.22%), weightlifting (19.49%), sailing (17.18%), table tennis (15.63%), and wrestling (14.74%).[19] The suspicion that young adolescent sportspersons could develop spondylolysis is crucial in early diagnosis and prevention of progression. Bracing and activity restriction has shown excellent results with a good return to the same level of play.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A high level of suspicion within sports coaches, general practitioners, and parents is needed to recognize patients with symptoms of spondylolisthesis.

Groups at risk like adolescent gymnasts, football players, and weight lifters should undergo health screening checks at regular intervals, and those with a history of lower back pain associated with activities undergo further evaluation and examination with those with suggestive signs and symptoms undergoing radiological investigations.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Spondylolisthesis Classification. Spondylolysis with spondylolisthesis, showing spinopelvic parameters, slip, dysplasia of upper endplate of S1, Slip angle (SA = angle between inferior endplate of L5 and a line perpendicular to the S1 posterior wall), and lumbosacral angle (LSA = angle between the superior endplate of L5 and posterior wall of the S1).

Contributed by G Ampat, MBBS, MS, FRCS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Toueg CW, Mac-Thiong JM, Grimard G, Parent S, Poitras B, Labelle H. Prevalence of spondylolisthesis in a population of gymnasts. Studies in health technology and informatics. 2010:158():132-7 [PubMed PMID: 20543413]

Mansfield JT, Wroten M. Pars Interarticularis Defect. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855876]

Bydon M, Alvi MA, Goyal A. Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis: Definition, Natural History, Conservative Management, and Surgical Treatment. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2019 Jul:30(3):299-304. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2019.02.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31078230]

Wiltse LL, Newman PH, Macnab I. Classification of spondylolisis and spondylolisthesis. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1976 Jun:(117):23-9 [PubMed PMID: 1277669]

Beutler WJ, Fredrickson BE, Murtland A, Sweeney CA, Grant WD, Baker D. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: 45-year follow-up evaluation. Spine. 2003 May 15:28(10):1027-35; discussion 1035 [PubMed PMID: 12768144]

DeWald CJ, Vartabedian JE, Rodts MF, Hammerberg KW. Evaluation and management of high-grade spondylolisthesis in adults. Spine. 2005 Mar 15:30(6 Suppl):S49-59 [PubMed PMID: 15767887]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcCleary MD, Congeni JA. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of spondylolysis in young athletes. Current sports medicine reports. 2007 Jan:6(1):62-6 [PubMed PMID: 17212915]

NATHAN H. Spondylolysis; its anatomy and mechanism of development. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1959 Mar:41-A(2):303-20 [PubMed PMID: 13630966]

Labelle H, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J, O'Brien M. The importance of spino-pelvic balance in L5-s1 developmental spondylolisthesis: a review of pertinent radiologic measurements. Spine. 2005 Mar 15:30(6 Suppl):S27-34 [PubMed PMID: 15767882]

Sairyo K, Nagamachi A, Matsuura T, Higashino K, Sakai T, Suzue N, Hamada D, Takata Y, Goto T, Nishisho T, Goda Y, Tsutsui T, Tonogai I, Miyagi R, Abe M, Morimoto M, Mineta K, Kimura T, Nitta A, Higuchi T, Hama S, Jha SC, Takahashi R, Fukuta S. A review of the pathomechanism of forward slippage in pediatric spondylolysis: the Tokushima theory of growth plate slippage. The journal of medical investigation : JMI. 2015:62(1-2):11-8. doi: 10.2152/jmi.62.11. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25817277]

Tebet MA. Current concepts on the sagittal balance and classification of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Revista brasileira de ortopedia. 2014 Jan-Feb:49(1):3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2014.02.003. Epub 2014 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 26229765]

Hanson DS, Bridwell KH, Rhee JM, Lenke LG. Correlation of pelvic incidence with low- and high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2002 Sep 15:27(18):2026-9 [PubMed PMID: 12634563]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoxall D, Bradford DS, Winter RB, Moe JH. Management of severe spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1979 Jun:61(4):479-95 [PubMed PMID: 438234]

Dubousset J. Treatment of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1997 Apr:(337):77-85 [PubMed PMID: 9137179]

Alvi MA, Sebai A, Yolcu Y, Wahood W, Elder BD, Kaufmann T, Bydon M. Assessing the Differences in Measurement of Degree of Spondylolisthesis Between Supine MRI and Erect X-Ray: An Institutional Analysis of 255 Cases. Operative neurosurgery (Hagerstown, Md.). 2020 Apr 1:18(4):438-443. doi: 10.1093/ons/opz180. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31381804]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRush JK, Astur N, Scott S, Kelly DM, Sawyer JR, Warner WC Jr. Use of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of spondylolysis. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2015 Apr-May:35(3):271-5. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000244. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24978120]

Labelle H, Mac-Thiong JM, Roussouly P. Spino-pelvic sagittal balance of spondylolisthesis: a review and classification. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2011 Sep:20 Suppl 5(Suppl 5):641-6. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1932-1. Epub 2011 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 21809015]

Steiner ME, Micheli LJ. Treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis with the modified Boston brace. Spine. 1985 Dec:10(10):937-43 [PubMed PMID: 3914087]

Tawfik S, Phan K, Mobbs RJ, Rao PJ. The Incidence of Pars Interarticularis Defects in Athletes. Global spine journal. 2020 Feb:10(1):89-101. doi: 10.1177/2192568218823695. Epub 2019 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 32002353]

O'Sullivan PB, Phyty GD, Twomey LT, Allison GT. Evaluation of specific stabilizing exercise in the treatment of chronic low back pain with radiologic diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1997 Dec 15:22(24):2959-67 [PubMed PMID: 9431633]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSinaki M, Lutness MP, Ilstrup DM, Chu CP, Gramse RR. Lumbar spondylolisthesis: retrospective comparison and three-year follow-up of two conservative treatment programs. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1989 Aug:70(8):594-8 [PubMed PMID: 2527488]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKraiwattanapong C, Wechmongkolgorn S, Chatriyanuyok B, Woratanarat P, Udomsubpayakul U, Chanplakorn P, Keorochana G, Wajanavisit W. Outcomes of fluoroscopically guided lumbar transforaminal epidural steroid injections in degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis patients. Asian spine journal. 2014 Apr:8(2):119-28. doi: 10.4184/asj.2014.8.2.119. Epub 2014 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 24761192]

Karsy M, Bisson EF. Surgical Versus Nonsurgical Treatment of Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2019 Jul:30(3):333-340. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2019.02.007. Epub 2019 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 31078234]

Buck JE. Direct repair of the defect in spondylolisthesis. Preliminary report. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1970 Aug:52(3):432-7 [PubMed PMID: 4916960]

Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H. Repair of defects in spondylolysis by segmental pedicular screw hook fixation. A preliminary report. Spine. 1996 Sep 1:21(17):2041-5 [PubMed PMID: 8883209]

Möller H, Hedlund R. Instrumented and noninstrumented posterolateral fusion in adult spondylolisthesis--a prospective randomized study: part 2. Spine. 2000 Jul 1:25(13):1716-21 [PubMed PMID: 10870149]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArts M, Pondaag W, Peul W, Thomeer R. Nerve root decompression without fusion in spondylolytic spondylolisthesis: long-term results of Gill's procedure. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2006 Oct:15(10):1455-63 [PubMed PMID: 16676154]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHu SS, Tribus CB, Diab M, Ghanayem AJ. Spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis. Instructional course lectures. 2008:57():431-45 [PubMed PMID: 18399601]

Ozgur BM, Aryan HE, Pimenta L, Taylor WR. Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF): a novel surgical technique for anterior lumbar interbody fusion. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2006 Jul-Aug:6(4):435-43 [PubMed PMID: 16825052]

Gaines RW, Nichols WK. Treatment of spondyloptosis by two stage L5 vertebrectomy and reduction of L4 onto S1. Spine. 1985 Sep:10(7):680-6 [PubMed PMID: 4071276]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMin K, Liebscher T, Rothenfluh D. Sacral dome resection and single-stage posterior reduction in the treatment of high-grade high dysplastic spondylolisthesis in adolescents and young adults. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2012 Aug:21 Suppl 6(Suppl 6):S785-91. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1949-5. Epub 2011 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 21800032]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchulte TL, Ringel F, Quante M, Eicker SO, Muche-Borowski C, Kothe R. Surgery for adult spondylolisthesis: a systematic review of the evidence. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2016 Aug:25(8):2359-67. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4177-6. Epub 2015 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 26363561]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceResnick DK, Watters WC 3rd, Sharan A, Mummaneni PV, Dailey AT, Wang JC, Choudhri TF, Eck J, Ghogawala Z, Groff MW, Dhall SS, Kaiser MG. Guideline update for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Part 9: lumbar fusion for stenosis with spondylolisthesis. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2014 Jul:21(1):54-61. doi: 10.3171/2014.4.SPINE14274. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24980586]

Parker SL, Mendenhall SK, Shau DN, Zuckerman SL, Godil SS, Cheng JS, McGirt MJ. Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis: comparative effectiveness and cost-utility analysis. World neurosurgery. 2014 Jul-Aug:82(1-2):230-8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.01.041. Epub 2013 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 23321379]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePetraco DM, Spivak JM, Cappadona JG, Kummer FJ, Neuwirth MG. An anatomic evaluation of L5 nerve stretch in spondylolisthesis reduction. Spine. 1996 May 15:21(10):1133-8; discussion 1139 [PubMed PMID: 8727186]

Cho KT, Lee HJ. Prone position-related meralgia paresthetica after lumbar spinal surgery : a case report and review of the literature. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2008 Dec:44(6):392-5. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2008.44.6.392. Epub 2008 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 19137086]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence