Introduction

Lipodermatosclerosis, also referred to as sclerosing panniculitis or hypodermitis sclerodermaformis, is a persistent inflammatory disorder characterized by the development of subcutaneous fibrosis and induration of the skin of the lower extremities. Huriez et al published the first account of lipodermatosclerosis in 1955, describing the findings of this condition.[1] The pathophysiologic mechanisms of this disease process are not well understood; several pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed. While existing evidence strongly supports the association between lipodermatosclerosis and venous insufficiency, irregularities in fibrinolysis have also been implicated.[2] The diffusion of capillary contents, including fibrinogen and other inflammatory mediators, into the dermis and subcutis, is thought to occur due to increased pressure within the venous circulation of the lower extremities.

Progressive fibrosing panniculitis ultimately leads to the classic appearance of lipodermatosclerosis, characterized by a lower extremity exhibiting an inverted champagne bottle shape. This classic description is representative of advanced-stage lipodermatosclerosis; the clinical presentation of this condition can vary significantly depending on the phase of the disease. The diagnosis is usually made clinically, relying solely upon hallmark features. In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, histological examination can provide confirmation.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Lipodermatosclerosis generally arises in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency, which can result from the loss of venous valvular integrity, an impediment to venous flow, or reduced functionality of the calf muscle pump. Several risk factors most commonly associated with developing chronic venous insufficiency and lipodermatosclerosis are obesity, aging, a prior history of deep venous thrombosis, a family history of venous insufficiency, and tobacco use. There is a higher incidence of chronic venous insufficiency in patients who are sedentary and those whose occupations involve prolonged periods of standing. Similarly, immobilization of the ankle joint can give rise to symptoms comparable to chronic venous insufficiency.[4]

A recent study employed venous Doppler ultrasonography and air plethysmography to determine that most patients with acute lipodermatosclerosis had underlying venous insufficiency, even without overt symptoms of chronic stasis. These findings support the prevailing theory that lipodermatosclerosis results from chronic venous disease.[1][2] While chronic venous insufficiency appears to be the driving force for developing lipodermatosclerosis, other factors may contribute. A connection between abnormalities of fibrinolysis and hypercoagulable states, such as protein C and S deficiencies, and the development of lipodermatosclerosis has been suggested, but the exact nature of this relationship is not fully understood.[5]

Epidemiology

Lipodermatosclerosis classically demonstrates a predilection for females; it is also associated with immobility and a high body mass index.[6] The incidence of lipodermatosclerosis is highest in middle-aged and older patients. While most cases of lipodermatosclerosis are diagnosed in women over 40, the onset of the disease process may occur as late as age 75.[7][8]

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of lipodermatosclerosis is likely multifactorial, with chronic venous insufficiency playing a significant role in driving key pathological alterations.[2] Chronic venous insufficiency and venous hypertension result in blood pooling in the lower extremities' venous system. The subsequent increase in capillary permeability promotes leukocyte accumulation within veins, which migrate into the adjacent tissue. These leukocytes undergo activation, emitting inflammatory mediators and cytokines and establishing a chronic inflammatory condition.[4] The leakage of fibrinogen and the formation of fibrin cuffs around vessels can disrupt oxygen exchange and contribute to tissue hypoxia, with a concurrent increase in collagen synthesis contributing to subcutaneous fat fibrosis.[8] There also appears to be a downregulation of angiogenesis in response to increased local expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (VEGFR-1) and angiopoietin-2.[9]. The downregulation of angiogenesis and increased activity of metalloproteinases predisposes the involved tissue of the lower extremities to ulceration.[1]

Chronic lesions of lipodermatosclerosis exhibit septal sclerosis, increased dermal fibroblast proliferation, and elevated expression of procollagen type 1 mRNA and transforming growth factor β1.[10][11] Advanced stages of lipodermatosclerosis are associated with reduced inflammation, decreased plasma fibrinolytic activity, low levels of proteins C and S, and alterations in matrix turnover.

The development of the characteristic manifestations of lipodermatosclerosis involves a complex interplay of underlying pathophysiological mechanisms that evolve throughout different stages of the disease. Additional research is needed to elucidate further each of the primary factors driving the pathogenesis of this condition.[5][8]

Histopathology

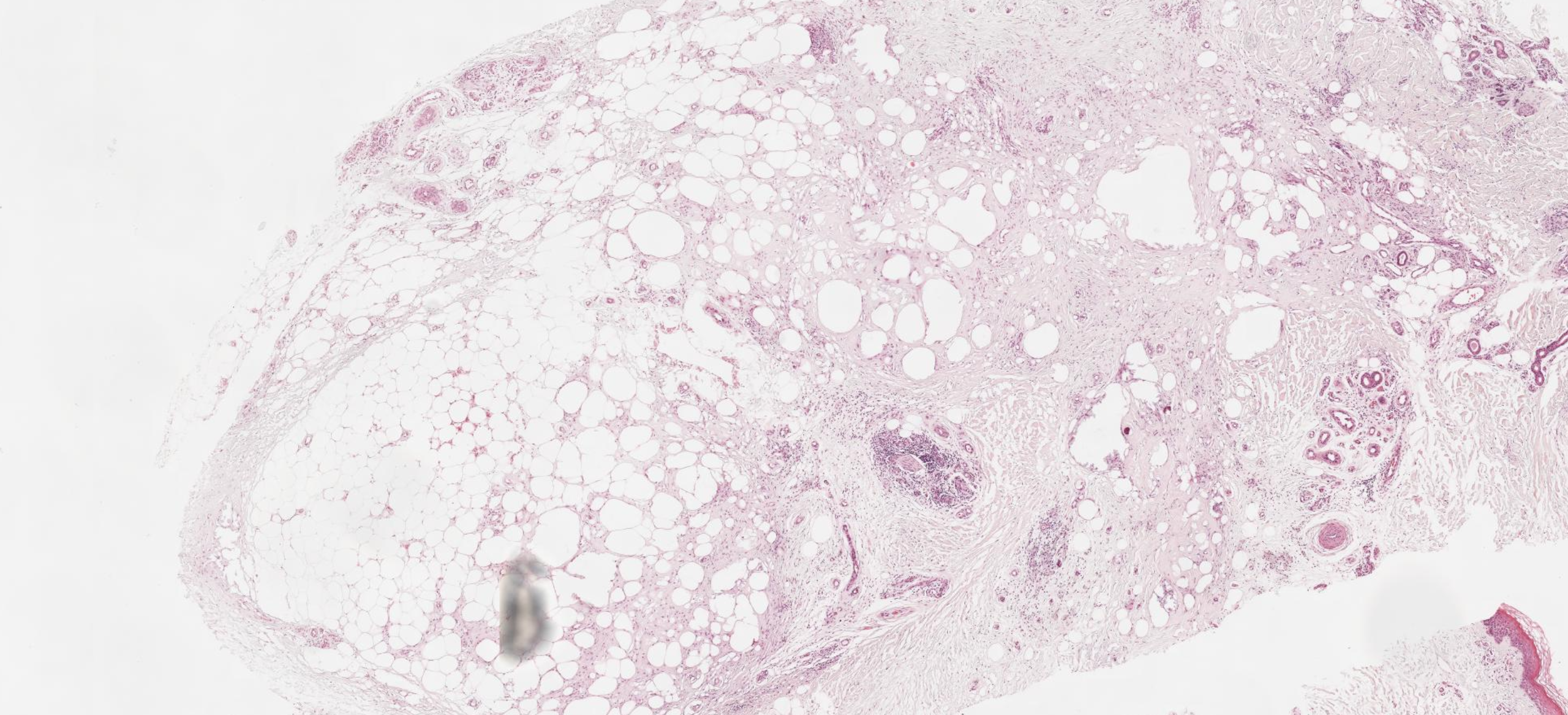

The histological appearance of lipodermatosclerosis will vary widely based on the evolutionary stage of the disease process. In the acute phase, there is often lymphocytic infiltration of the septa surrounding fat lobules with cystic fat necrosis and capillary hemorrhage accompanied by hemosiderin deposition (see Image. Lipodermatosclerosis on Histology).

The characteristic histopathological features of more advanced lipodermatosclerosis generally include lobular panniculitis with a mixed cellular infiltrate, breakdown of adipocytes, and lipomembranous change leading to the formation of "pseudocysts" within the subcutaneous tissue.[7] The lipomembranous change is defined by deteriorating adipocytes with thick, eosinophilic borders and is a histologic feature highly suggestive of lipodermatosclerosis.[12] Additionally, chronic lipodermatosclerosis is associated with significant septal fibrosis and hyaline sclerosis superimposed on a background of chronic stasis changes.[7]

Various staining techniques can be employed to highlight the presence of perivascular fibrin cuffing, which can aid in establishing the diagnosis of lipodermatosclerosis.[12] Despite varying degrees of panniculitis and necrosis, vasculitis is not commonly associated with lipodermatosclerosis and is not generally appreciable at any point of disease progression.[13]

History and Physical

Lipodermatosclerosis typically occurs in patients with a history of chronic venous insufficiency and will often be accompanied by chronic venous stasis changes such as venous varicosities, scarring from prior ulcerations, and pitting edema of the lower extremities. Hyperpigmentation is also common in individuals with lipodermatosclerosis and is attributed to hemosiderin deposition (see Image. Lipodermatosclerosis).[7] Classically, lipodermatosclerosis presents bilaterally across the lower limbs. However, one study of 97 patients with lipodermatosclerosis demonstrated bilateral involvement of the lower extremities in only 45% of cases.[14]

Lipodermatosclerosis can be categorized by the length of time symptoms have been present: acute (<1 month), subacute (1 month to 1 year), and chronic (>1 year).[15] The presentation of subacute lipodermatosclerosis varies widely, often displaying acute and chronic lipodermatosclerosis features.[15][3]

The acute phase of the disease is typically associated with isolated, tender, poorly demarcated, erythematous plaques, which can be mistaken for a bacterial infection; many patients are initially treated with antibiotic therapy for cellulitis in the acute stage. At the time of onset, the initial lesions and accompanying tenderness are generally more prominent in the medial leg, particularly above the medial malleolus.[1]

The chronic phase of lipodermatosclerosis is characterized by well-defined, circumferential, thick, darkly pigmented, nontender plaques. These plaques are often described as having a firm, “woody” induration, and the sclerotic change with circumferential narrowing of the lower leg and concurrent proximal and distal edema produces the classic “inverted champagne bottle” appearance of the lower extremity (see Image. Venous Insufficiency and Lipodermatosclerosis). The rounded cork of the champagne bottle is symbolic of the edematous foot, the central fibrosis around the ankle represents the neck, and the bottle's body embodies the lymphedema proximal to the area of constriction.

Evaluation

The evaluation of lipodermatosclerosis begins with obtaining a comprehensive medical history and performing a thorough physical examination. In most cases, the diagnosis of lipodermatosclerosis is determined by clinical features alone and can be treated empirically without additional diagnostic testing.[16] However, further investigation with biopsy and histological evaluation should be considered in any patient not responding to first-line therapy or deviating from the expected clinical course. In general, when considering panniculitides of the lower extremities, biopsy should be avoided initially if possible due to this anatomic region's characteristically poor wound healing ability.

When the pathophysiology of a disease process is suspected to occur predominantly beneath the dermis, the tissue obtained with biopsy must contain a significant amount of subcutaneous tissue for histopathological analysis. The fibrous thickening in the lower dermis in lipodermatosclerosis poses a challenge for smaller punch biopsies as they may not capture subcutaneous fat from the affected skin area. Consequently, tissue is best obtained via an elliptical excisional biopsy or a 6-mm to 8-mm punch biopsy. However, as many patients with chronic venous insufficiency and lipodermatosclerosis demonstrate poor wound healing, excisional biopsy will likely result in a more cosmetic outcome. The location of the highest diagnostic yield for biopsy is the peripheral margin of the lesion of interest rather than the area of central involvement.

Patients suspected to have lipodermatosclerosis typically do not require laboratory, radiographic, or other diagnostic testing.[17] In cases where the biopsy is inconclusive, or the patient exhibits findings concurrent with a more critical disease state, additional testing may be warranted.[10]

Treatment / Management

The data regarding the effectiveness of differing treatment approaches to lipodermatosclerosis is primarily derived from case studies, as only a limited number of sizeable clinical trials are available.[14] However, initial management options for lipodermatosclerosis generally employ compression therapy combined with leg elevation. These methods aid in alleviating associated symptoms and disease progression. Using mechanical compression therapy with compression stockings and elevation of the lower extremities is the foundation for managing lipodermatosclerosis by facilitating venous blood flow, minimizing edema, and reducing pain [18].(B2)

For acute lipodermatosclerosis, topical corticosteroids have demonstrated benefit in reducing symptoms. Intralesional corticosteroids can be employed if the presentation is limited to several isolated, indurated plaques. However, topical application is preferred if the affected area is more diffuse or circumferential. Adjunctive management methods for lipodermatosclerosis include increasing physical activity and weight reduction. Physical activity should be encouraged to improve the functionality of the calf muscle pump, and weight reduction is particularly effective if obesity is present.[19]

Systemic therapy with oral anabolic steroids has proven effective for chronic lipodermatosclerosis or acute disease unresponsive to initial therapies.[13] Specifically, positive outcomes have been documented following oral administration of danazol and oxandrolone.[20] Stanozolol, no longer available by prescription in the United States, has also demonstrated therapeutic benefits and reduces dermal thickness.[18] These oral anabolic agents augment fibrinolysis and exhibit the potential to alleviate pain, decrease skin induration, and limit disease extent. Nevertheless, their utility is hindered by adverse effects such as sodium retention, lipid profile abnormalities, hepatotoxicity, and the potential for virilization in females. Consequently, oral anabolic steroids are generally contraindicated for patients with uncontrolled hypertension or heart failure.[21](B3)

Interventional therapy may be an option for patients whose lipodermatosclerosis has proven refractory to systemic therapeutic options. Ultrasound treatment for lipodermatosclerosis was first described more than 25 years ago. Since then, numerous smaller trials have been conducted on its effectiveness, and recent studies have demonstrated promising results in reducing hardness and erythema when ultrasound is combined with compression stockings. This treatment approach may potentially reverse the associated fibrotic and inflammatory changes. Consequently, ultrasound therapy can safely be incorporated into the treatment regimen of those resistant to initial therapies.[22](B3)

Other adjunct therapies, such as capsaicin cream, may address the chronic pain associated with lipodermatosclerosis but do not prevent disease progression. Additionally, for patients with lipodermatosclerosis where nonsurgical and systemic therapy fails, a referral to a vascular surgeon or interventional radiologist may be required to treat underlying varicosities.[23]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for lipodermatosclerosis will include many conditions depending on the stage of the disease. The acute stage of lipodermatosclerosis is often mistaken for conditions such as cellulitis, erythema nodosum, trauma-induced fat necrosis, and other panniculitides.[24] When encountering well-defined, hardened, and extremely tender plaques affecting the lower legs that resemble cellulitis, clinicians should always consider the possibility of lipodermatosclerosis.

If the patient does not respond to first-line therapies for lipodermatosclerosis or deviates from the expected clinical course, a biopsy of the lesion will aid in culling the differential diagnosis. On histopathological evaluation, cellulitis is characterized by perivascular inflammation predominantly composed of neutrophils, and a complete blood count may be performed if an infection is suspected.[25] In comparison, erythema nodosum presents with septal panniculitis and a mixed cellular infiltrate without vasculitis and is characterized by a prominent granulomatous infiltrate with giant cells.[26] Fat necrosis manifests as isolated lesions, often associated with a history of trauma.[27]

During the subacute and chronic stages of lipodermatosclerosis, the differential diagnosis includes several conditions not typically considered in the acute phase, such as morphea, necrobiosis lipoidica, and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Morphea presents with ivory-colored, indurated plaques with a characteristic purple-colored ring and, microscopically, demonstrates thick collagen bundles without lipomembranous dystrophy.[28] Necrobiosis lipoidica manifests as asymptomatic patches or yellow or red plaques with an alternating, layered inflammatory process seen on histopathological evaluation.[29] Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is associated with gadolinium exposure in individuals with impaired renal function.[30]

Prognosis

Studies assessing the prognosis and treatment course of lipodermatosclerosis demonstrate variability in disease timeline and outcomes. A recent investigation involving nearly 30 patients reported the complete resolution of acute-phase symptoms in all cases through compression bandages. However, upon discontinuing the compression therapy, approximately 50% of patients progressed to the chronic stage of lipodermatosclerosis over the next 12 months, while the remaining 50% did not exhibit further disease advancement.[16] Nevertheless, most conditions associated with venous insufficiency manifest as chronic and recurrent conditions, including lipodermatosclerosis. Despite the potential for treatment to lessen symptoms and decelerate disease progression, lipodermatosclerosis typically follows a prolonged and advancing course.[19]

Complications

The chronic stage of lipodermatosclerosis is frequently regarded as a distinct phase preceding ulceration, characterized by impaired wound healing due to the persistent inflammatory state and fibrosis. However, venous ulcers often coexist with lipodermatosclerosis (see Image. Chronic Lipodermatosclerosis and Venous Stasis Ulceration).[3] Numerous studies have suggested a direct correlation between the extent of skin induration, subsequent ulceration risk, and healing potential. Even minor traumas like scratching can lead to ulcers in individuals with substantial induration.

Another potential complication of lipodermatosclerosis is lower extremity pain, recently identified by a case series as the foremost persistent symptom observed in patients with lipodermatosclerosis. The acute phase of lipodermatosclerosis is classically accompanied by severe, burning pain; individuals with more advanced lipodermatosclerosis may develop chronic, aching pain in the lower extremities.[1]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Although the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, the relationship between chronic venous insufficiency and the development of lipodermatosclerosis is well-established.[14] Close monitoring of patients with chronic venous insufficiency is essential for the early prevention and detection of associated complications and improvement in long-term outcomes.[4] Lifestyle interventions, including physical activity and leg elevation, are recommended to reduce edema in individuals with chronic venous insufficiency. Compression stockings may be added if lifestyle measures are ineffective, and patients must be instructed in their proper use to achieve compliance. Compression therapy has been shown to reduce edema, prevent vascular compromise, and promote the healing of lower extremity wounds while minimizing recurrences.[18] Individuals who use tobacco products or have a high body mass index are at an increased risk of developing chronic venous insufficiency and subsequent lipodermatosclerosis. Therefore, weight loss and smoking cessation are also recommended interventions.[31]

Prompt intervention of chronic venous insufficiency in its early stages can effectively prevent the subsequent onset of lipodermatosclerosis. Consequently, in cases where initial therapeutic measures have failed to alleviate associated edema and skin alterations, patients should be referred for a comprehensive duplex examination of the lower extremities to confirm the diagnosis of chronic venous insufficiency. This investigative approach serves to validate the presence of venous reflux. The study must be conducted by a qualified vascular sonographer, interventional radiologist, or vascular surgeon with the necessary duplex ultrasound expertise. Optimal visualization of lower extremity veins is achieved when the veins are maximally dilated. To facilitate venous distension, the examination should be performed with the patient upright, replicating the intravascular pressure within the veins during standing.[32] Studies conducted while supine may produce false negative results. For patients with confirmed, symptomatic varicose veins and venous reflux with lipodermatosclerosis or a history of ulceration, early intervention through venous ablation is recommended to prevent disease progression and mitigate further skin alterations.[33]

Anyone who develops a new skin lesion with unknown characteristics to seek evaluation from a dermatologist or other healthcare professional. The acute onset of lipodermatosclerosis can lead to tender lesions resembling cellulitis, requiring a comprehensive assessment to determine the potential need for antibiotic therapy. If left untreated, long-lasting fibrosis can occur, leading to recurrent ulceration and permanent scarring in affected individuals.[1]

Patients diagnosed with chronic venous insufficiency or lipodermatosclerosis should be educated about the importance of monitoring and maintaining the skin barrier, including regular inspection of the skin for local injury and signs of infection and meticulous application of emollients to inhibit the formation of fissures or ulceration. Patients should receive education on proper wound care and be encouraged to seek specialized care from wound care specialists when ulcers develop.[34] It is vital to inform patients about all available medical therapies for lipodermatosclerosis, including potential adverse effects. Furthermore, patients should know that lipodermatosclerosis and venous disease are chronic conditions requiring diligent commitment to the prescribed treatment regimen and continuing care with healthcare providers to prevent progression and complications.[35]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lipodermatosclerosis is a complication of chronic venous insufficiency, and effective management of the underlying venous disease is crucial for preventing and managing lipodermatosclerosis. Consequently, lipodermatosclerosis requires a multidisciplinary, interprofessional approach for optimal management. The healthcare team might include a primary care practitioner, dermatologist, wound care nurse, physical therapist, dietician, pharmacist, vascular surgeon, and interventional radiologist.

Primary care providers are most likely to establish the initial diagnosis and primary management of chronic venous insufficiency, ruling out other causes of lower limb edema and assessing for the possibility of underlying infection.[35] Pharmacists can review medications, identify medications that exacerbate vasodilation, and assist in developing alternative treatment plans. Referral to dermatology for further evaluation is recommended once associated skin changes develop; this evaluation may include skin biopsy and administration of topical or systemic therapies. Consultation with wound care specialists and nursing can be considered when addressing complications like venous ulcers. Ultimately, patients may require referral to interventional radiology, general surgery, or vascular surgery experts in non-healing ulcers or disease recurrence cases.[36] Close patient follow-up is essential to prevent disease progression and recurrence. Effective communication and interprofessional collaboration among healthcare team members ensure safe and effective treatment, optimizing patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Chronic Lipodermatosclerosis and Venous Stasis Ulceration. Pictured are the typical ulcer features of a shallow wound base, irregular borders, healthy red granulation tissue, and surrounding lipodermatosclerosis in the classic region of the lower medial leg, also referred to as the gaiter region.

Contributed by MA Dreyer, DPM, FACFAS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Miteva M, Romanelli P, Kirsner RS. Lipodermatosclerosis. Dermatologic therapy. 2010 Jul-Aug:23(4):375-88. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01338.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20666825]

Greenberg AS, Hasan A, Montalvo BM, Falabella A, Falanga V. Acute lipodermatosclerosis is associated with venous insufficiency. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996 Oct:35(4):566-8 [PubMed PMID: 8859285]

Kaya Ö, Kaya H. Stasis dermatitis: A skin manifestation of poor prognosis in patients with heart failure. Hippokratia. 2022 Jan-Mar:26(1):13-18 [PubMed PMID: 37124274]

Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Smith PD, Nicolaides AN, Boisseau MR, Eklof B. Chronic venous disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Aug 3:355(5):488-98 [PubMed PMID: 16885552]

Falanga V, Bontempo FA, Eaglstein WH. Protein C and protein S plasma levels in patients with lipodermatosclerosis and venous ulceration. Archives of dermatology. 1990 Sep:126(9):1195-7 [PubMed PMID: 2144413]

Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Lipodermatosclerosis: a clinicopathological study of 25 cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010 Jun:62(6):1005-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20466175]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJorizzo JL, White WL, Zanolli MD, Greer KE, Solomon AR, Jetton RL. Sclerosing panniculitis. A clinicopathologic assessment. Archives of dermatology. 1991 Apr:127(4):554-8 [PubMed PMID: 2006882]

Kirsner RS, Pardes JB, Eaglstein WH, Falanga V. The clinical spectrum of lipodermatosclerosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1993 Apr:28(4):623-7 [PubMed PMID: 8463465]

Herouy Y, Kreis S, Mueller T, Duerk T, Martiny-Baron G, Reusch P, May F, Idzko M, Norgauer Y. Inhibition of angiogenesis in lipodermatosclerosis: implication for venous ulcer formation. International journal of molecular medicine. 2009 Nov:24(5):645-51 [PubMed PMID: 19787198]

Ortega MA, Fraile-Martínez O, García-Montero C, Álvarez-Mon MA, Chaowen C, Ruiz-Grande F, Pekarek L, Monserrat J, Asúnsolo A, García-Honduvilla N, Álvarez-Mon M, Bujan J. Understanding Chronic Venous Disease: A Critical Overview of Its Pathophysiology and Medical Management. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021 Jul 22:10(15):. doi: 10.3390/jcm10153239. Epub 2021 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 34362022]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDegiorgio-Miller AM, Treharne LJ, McAnulty RJ, Coleridge Smith PD, Laurent GJ, Herrick SE. Procollagen type I gene expression and cell proliferation are increased in lipodermatosclerosis. The British journal of dermatology. 2005 Feb:152(2):242-9 [PubMed PMID: 15727634]

Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK, Aliaga A. Lipomembranous changes in chronic panniculitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1988 Jul:19(1 Pt 1):39-46 [PubMed PMID: 3042817]

Requena C, Sanmartín O, Requena L. Sclerosing panniculitis. Dermatologic clinics. 2008 Oct:26(4):501-4, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.06.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18793983]

Bruce AJ, Bennett DD, Lohse CM, Rooke TW, Davis MD. Lipodermatosclerosis: review of cases evaluated at Mayo Clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002 Feb:46(2):187-92 [PubMed PMID: 11807428]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSuehiro K, Morikage N, Harada T, Samura M, Nagase T, Mizoguchi T, Hamano K. Compression Therapy Using Bandages Successfully Manages Acute or Subacute Lipodermatosclerosis. Annals of vascular diseases. 2019 Mar 25:12(1):77-79. doi: 10.3400/avd.cr.18-00135. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30931064]

Suehiro K, Morikage N, Harada T, Takeuchi Y, Mizoguchi T, Ike S, Otuska R, Kurazumi H, Suzuki R, Hamano K. Post-treatment course of acute lipodermatosclerosis. Phlebology. 2023 Mar:38(2):73-79. doi: 10.1177/02683555221147473. Epub 2022 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 36529929]

Diaz Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W. Panniculitis: definition of terms and diagnostic strategy. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2000 Dec:22(6):530-49 [PubMed PMID: 11190446]

Vesić S, Vuković J, Medenica LJ, Pavlović MD. Acute lipodermatosclerosis: an open clinical trial of stanozolol in patients unable to sustain compression therapy. Dermatology online journal. 2008 Feb 28:14(2):1 [PubMed PMID: 18700104]

Bonkemeyer Millan S, Gan R, Townsend PE. Venous Ulcers: Diagnosis and Treatment. American family physician. 2019 Sep 1:100(5):298-305 [PubMed PMID: 31478635]

Hafner C, Wimmershoff M, Landthaler M, Vogt T. Lipodermatosclerosis: successful treatment with danazol. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2005:85(4):365-6 [PubMed PMID: 16191868]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSegal S, Cooper J, Bolognia J. Treatment of lipodermatosclerosis with oxandrolone in a patient with stanozolol-induced hepatotoxicity. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2000 Sep:43(3):558-9 [PubMed PMID: 10954677]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDamian DL, Yiasemides E, Gupta S, Armour K. Ultrasound therapy for lipodermatosclerosis. Archives of dermatology. 2009 Mar:145(3):330-2. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.24. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19289773]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChokkalingam Mani B, Delgado GA. Varicose Vein Treatment: Radiofrequency Ablation Therapy. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310580]

Bailey E, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: diagnosis and management. Dermatologic therapy. 2011 Mar-Apr:24(2):229-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2011.01398.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21410612]

Brown BD, Hood Watson KL. Cellulitis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31747177]

Pérez-Garza DM, Chavez-Alvarez S, Ocampo-Candiani J, Gomez-Flores M. Erythema Nodosum: A Practical Approach and Diagnostic Algorithm. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2021 May:22(3):367-378. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00592-w. Epub 2021 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 33683567]

Akyol M, Kayali A, Yildirim N. Traumatic fat necrosis of male breast. Clinical imaging. 2013 Sep-Oct:37(5):954-6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.05.009. Epub 2013 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 23849832]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChiu YE, Abban CY, Konicke K, Segura A, Sokumbi O. Histopathologic Spectrum of Morphea. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2021 Jan 1:43(1):1-8. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001662. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33337624]

Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis Lipoidica. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083569]

Shamam YM, De Jesus O. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33620831]

Gourgou S, Dedieu F, Sancho-Garnier H. Lower limb venous insufficiency and tobacco smoking: a case-control study. American journal of epidemiology. 2002 Jun 1:155(11):1007-15 [PubMed PMID: 12034579]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNecas M. Duplex ultrasound in the assessment of lower extremity venous insufficiency. Australasian journal of ultrasound in medicine. 2010 Nov:13(4):37-45. doi: 10.1002/j.2205-0140.2010.tb00178.x. Epub 2015 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 28191096]

A Randomized Trial of Early Endovenous Ablation in Venous Ulceration., Gohel MS,Heatley F,Liu X,Bradbury A,Bulbulia R,Cullum N,Epstein DM,Nyamekye I,Poskitt KR,Renton S,Warwick J,Davies AH,, The New England journal of medicine, 2018 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 29688123]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCollins L, Seraj S. Diagnosis and treatment of venous ulcers. American family physician. 2010 Apr 15:81(8):989-96 [PubMed PMID: 20387775]

Klejtman T, Lazareth I, Yannoutsos A, Priollet P. Specific management of lipodermatosclerosis (sclerotic hypodermitis) in acute and chronic phase. Journal de medecine vasculaire. 2022 Oct:47(4):186-190. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmv.2022.10.006. Epub 2022 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 36344029]

Patel SK, Surowiec SM. Venous Insufficiency. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613694]