Introduction

The aorta is the largest vessel within the human body. It originates from the left ventricle of the heart anterior to the pulmonary artery before arching posteriorly and descending along the posterior mediastinum. It descends to the level of the L4 vertebral body where it bifurcates into the left and right common iliac arteries. It is the main artery in the body and distributes oxygenated blood to the entire systemic circulation. This section will be limited to the thoracic portion of the aorta, which includes the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and descending thoracic aorta before it crosses the level of the diaphragm where it becomes the abdominal aorta. The thoracic aorta is responsible for supplying oxygenated blood to multiple structures, including the head, neck, upper extremities, and thoracic structures.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The thoracic aorta originates from the left ventricle, guarded by the aortic valve. Just above the cusp of the aortic valve, the aorta gives off the left and right main coronary arteries that run along coronary grooves of the heart and are responsible for perfusion of the myocardium. The initial portion of the aorta ascending behind the sternum is referred to as the ascending aorta, extends approximately to the level of the T4 vertebral body. From this point, it is known as the aortic arch and begins to arch posteriorly and to the left of the vertebral bodies in the posterior mediastinum. The aortic arch both begins and ends at the level of the second rib; it lies within the superior mediastinum. in the chest radiographs, the aortic arch is identifiable as "the aortic knob." The aortic arch gives off three branches including:

- Brachiocephalic artery (also known as the innominate artery) is the first arch vessel to branch off - it travels superiorly and to the right side of the body and bifurcates into the right subclavian artery and right common carotid artery

- The left common carotid artery is the subsequent vessel to branch from the aortic arch

- Left subclavian artery is the third arch vessel to branch from the aortic arch

The final section of the aortic arch is just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery and is known as the aortic isthmus. There is a mild narrowing of the aorta that occurs at the site of the ligamentum arteriosum, which is a remnant of the ductus arteriosus. From the fourth thoracic vertebra, it continues as the descending aorta to travels downward to the diaphragmatic hiatus at the level of T12 where it exits the thorax. The descending aorta gives off multiple vessels before exiting the thoracic cavity, including arteries to supply the pericardium, bronchi, mediastinum, and esophagus; it also gives off the superior phrenic arteries, posterior intercostal arteries, and subcostal arteries.

Embryology

The aorta develops during the third gestational week.[1] The ascending aorta and aortic arch develop independently from two different embryologic tracts. The ascending aorta develops from the truncus arteriosus which is a component of heart development. The truncus arteriosus is a single outflow tract that forms during heart development. It originates from both the left and right ventricle of the heart. The truncus arteriosus is then divided by the aorticopulmonary septum to give rise to two separate outflow tracts, later known as the pulmonary artery and ascending aorta.

The aortic arch forms through the development of the branchial arch arteries. There are six branchial arch arteries, also known as the pharyngeal arch vessels. These develop into the following[2][3]:

- The first branchial arch artery forms the maxillary and external carotid arteries

- The second branchial arch artery leads to the formation of the stapedial arteries

- The third branchial arch artery contributes to the formation of the right common carotid arteries and proximal internal carotid artery

- The fourth branchial arch artery forms the main portion of the aortic arch, as well as the proximal right subclavian artery - the left subclavian artery arises from the left seventh intersegmental artery, which describes a set of arteries that develop from the dorsal aorta

- The fifth branchial arch does not form vessels and regresses

- The sixth branchial arch leads to the formation of the main pulmonary artery, left and right pulmonary artery, and ductus arteriosus

Surgical Considerations

Coarctation of the aorta

Coarctation of the aorta refers to a congenital condition in which the aorta narrows, obstructing distal blood flow; this most commonly occurs in proximity to the ductus arteriosus with classifications of preductal coarctation, ductal coarctation, and postductal coarctation.

Preductal coarctation occurs proximal to the ductus arteriosus; this most often occurs as a result of a congenital heart anomaly the leads to decreased blood flow to the left side of the heart and aorta, resulting in hypoplastic development.

Ductal coarctation occurs at the insertion of the ductus arteriosus and most often appears at birth as the ductus arteriosus obliterates.

Postductal coarctation occurs distal to the ductus arteriosus, which is the most common form in adults. It often presents as hypertension in the upper extremities and weak pulses in the lower extremities. This presentation is due to increased blood flow through the aortic arch vessels and decreased blood flow to the descending aorta distal to the stenotic segment. Collateral vessels may increase in size to aid in the delivery of blood to the descending aorta. This collateralization most often occurs through the subclavian artery into the internal thoracic artery which goes to the anterior intercostal artery, to the posterior intercostal artery, and finally into the descending thoracic aorta. The dilation of the intercostal arteries may result in the characteristic finding of rib notching on chest x-ray.[4][5]

Coarctation of the aorta results in significant morbidity in patients with severe narrowing and poor outcome in patients who survive beyond one year of age.[6] Treatment options include surgical repair, balloon angioplasty, and endovascular stent placement. Although these options are available, the decision on an optimal treatment strategy can be complicated. There is not a standard of care practice or algorithm in treating these patients.[7] Management is at the physician's discretion with age at presentation and complexity of coarctation influencing treatment choice.

Clinical Significance

Aortic aneurysm

A thoracic aortic aneurysm refers to a dilatation of the proximal ascending aorta; this is most often the result of chronic hypertension when seen in adults. In young adults, the most common underlying factor is a connective tissue disorder such as Marfan syndrome or Ehler-Danlos syndrome. An aortic aneurysm is of concern because dilation of the aorta results in weakening of the aortic wall, increasing risk of aortic rupture or dissection. For this reason, elective repair is often the recommendation once an aneurysm has reached a diameter of 5.5cm or greater.[8][9] Elective repair can reduce the risk of rupture and survival to near normal.

Aortic dissection

Aortic dissection refers to the disruption of the innermost layer of the aorta, allowing blood to tunnel through the central portion of the aortic wall. It most often occurs at the proximal portion of the ascending aorta, just distal to the aortic valve. Aortic dissections can then propagate distally or proximally through the aortic wall. Aortic dissections are a life-threatening emergency that requires surgical repair to increase the chances of survival. Nearly 40% of patients with acute aortic dissections expire immediately. Of those who survive the initial event, approximately 80% will die within two weeks.[10]

Patent ductus arteriosus

The ductus arteriosus is a communication between the pulmonary artery and the aortic arch in fetal life. It usually closes by the second day after birth in full-term babies. If this communication persists beyond two days, it is called patent ductus arteriosus. Depending upon the size of patency this condition can lead to failure to thrive and heart failure.[1]

Other aberrant conditions of development seen in the aorta are hypoplastic ascending aorta, interrupted aortic arch, right aortic arch, and double aortic arch.[1]

Media

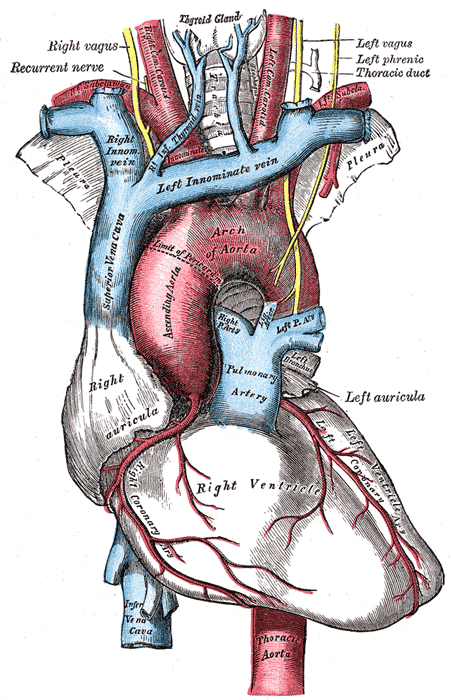

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Branches of the Aorta. This illustration includes the right common carotid artery, right vertebral artery, right subclavian artery, brachiocephalic artery, ascending aorta, left coronary artery, right coronary artery, left common carotid artery, left vertebral artery, left subclavian artery, left axillary artery, left brachial artery, arch of aorta, and descending aorta.

Contributed by Beckie Palmer

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kau T, Sinzig M, Gasser J, Lesnik G, Rabitsch E, Celedin S, Eicher W, Illiasch H, Hausegger KA. Aortic development and anomalies. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2007 Jun:24(2):141-52. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-980040. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21326792]

Dungan DH, Heiserman JE. The carotid artery: embryology, normal anatomy, and physiology. Neuroimaging clinics of North America. 1996 Nov:6(4):789-99 [PubMed PMID: 8824131]

Bamforth SD, Chaudhry B, Bennett M, Wilson R, Mohun TJ, Van Mierop LH, Henderson DJ, Anderson RH. Clarification of the identity of the mammalian fifth pharyngeal arch artery. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2013 Mar:26(2):173-82. doi: 10.1002/ca.22101. Epub 2012 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 22623372]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, Bozkurt B, Broberg CS, Colman JM, Crumb SR, Dearani JA, Fuller S, Gurvitz M, Khairy P, Landzberg MJ, Saidi A, Valente AM, Van Hare GF. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019 Apr 2:139(14):e698-e800. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30586767]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKaraosmanoglu AD, Khawaja RD, Onur MR, Kalra MK. CT and MRI of aortic coarctation: pre- and postsurgical findings. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2015 Mar:204(3):W224-33. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12529. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25714305]

Campbell M. Natural history of coarctation of the aorta. British heart journal. 1970 Sep:32(5):633-40 [PubMed PMID: 5470045]

Torok RD,Campbell MJ,Fleming GA,Hill KD, Coarctation of the aorta: Management from infancy to adulthood. World journal of cardiology. 2015 Nov 26; [PubMed PMID: 26635924]

Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Hammond GL, Kopf GS, Elefteriades JA. Surgical intervention criteria for thoracic aortic aneurysms: a study of growth rates and complications. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1999 Jun:67(6):1922-6; discussion 1953-8 [PubMed PMID: 10391339]

Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Hammond GL, Mandapati D, Darr U, Kopf GS, Elefteriades JA. What is the appropriate size criterion for resection of thoracic aortic aneurysms? The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1997 Mar:113(3):476-91; discussion 489-91 [PubMed PMID: 9081092]

Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Goldstein LJ, Elefteriades JA. Natural history, pathogenesis, and etiology of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Cardiology clinics. 1999 Nov:17(4):615-35; vii [PubMed PMID: 10589336]