Introduction

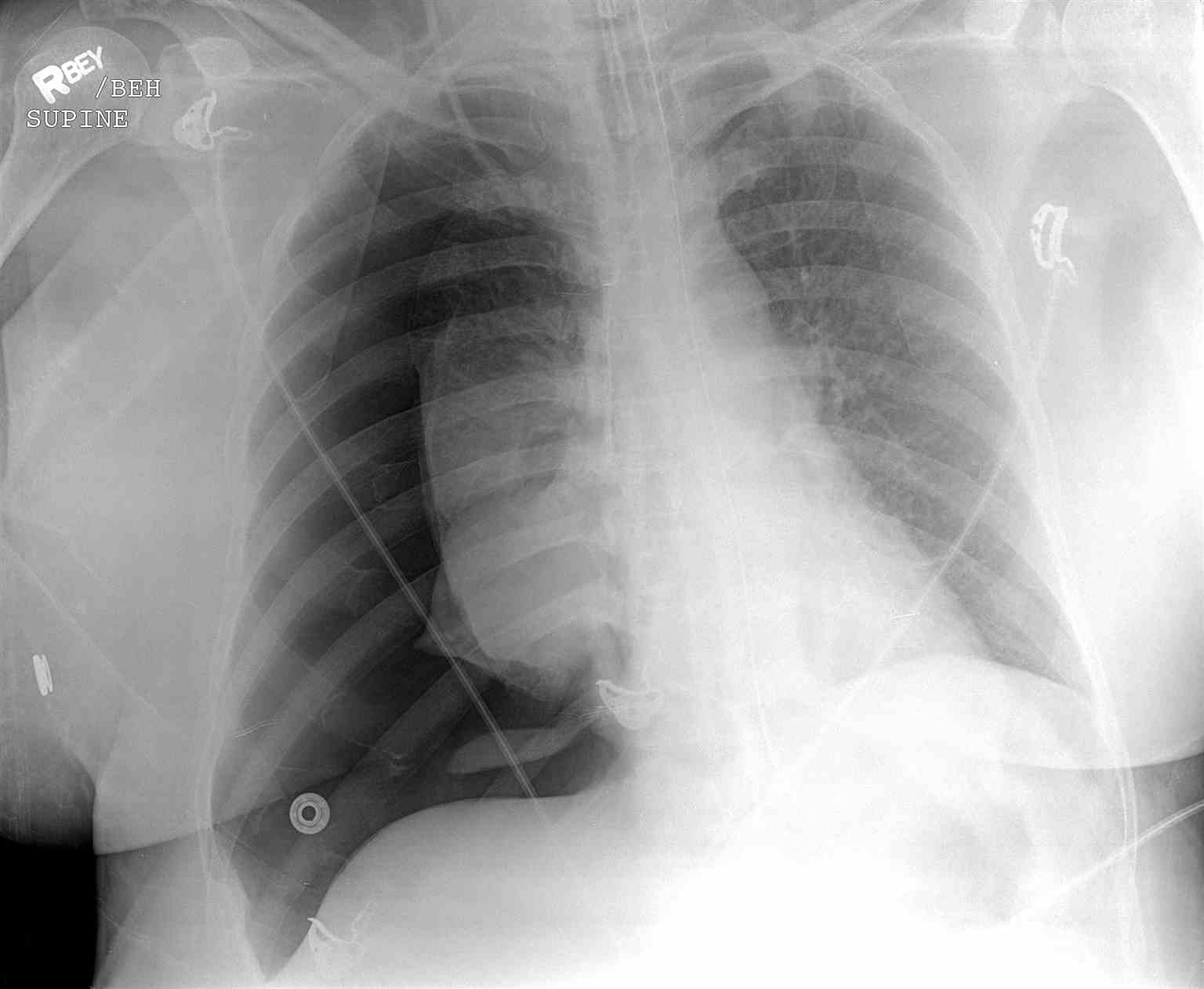

Pneumothorax is air collection in the pleural space, resulting in lung collapse from positive pleural pressure. Tension pneumothorax occurs when pleural pressure is transmitted to the mediastinum (see Image. Left-Sided Tension Pneumothorax Radiograph). This uncommon condition has a malignant course and might result in death if left untreated.[1][2] Tension pneumothorax may arise in the prehospital setting, emergency department, and intensive care unit.[3][4][5][6]

The thorax has 3 compartments: the right and left pulmonary cavities and the centrally located mediastinum. The pulmonary cavities are lined internally by the parietal pleura. The visceral or pulmonary pleura wraps around the lungs. The pleural cavity is the potential space between the parietal and visceral pleurae. Serous pleural fluid normally lubricates the pleural surfaces.

Diaphragmatic depression and the ribs' outward motion expand the lungs during normal inspiration. The lungs increase in size as the pleural pressure becomes slightly negative. Normal expiration occurs with diaphragmatic elevation and slight inward motion of the ribs. The positive pleural pressure pushes the air out of the lungs.

Pleural disruption can introduce air into the pleural cavity. Positive pleural pressure can cause lung contraction, reducing oxygenation and ventilation in the affected lung. High positive pleural pressure can also compress the mediastinum and its structures, notably the heart, great blood vessels, and the trachea. Tension pneumothorax arises, compromising respiration, venous return, and cardiac output.

Early recognition and management of tension pneumothorax saves lives. Rapid administration of emergency thoracic decompression is a skill all healthcare professionals must have.[7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Pneumothorax can be traumatic or atraumatic. Outside of the hospital, traumatic pneumothorax may arise from penetrating or blunt trauma, rib fractures, and pulmonary decompression sickness.[8][9] In the hospital setting, traumatic pneumothorax may arise iatrogenically from the following procedures:[10]

- Central venous catheterization (CVC) in the subclavian or internal jugular vein

- Lung biopsy

- Barotrauma due to positive pressure ventilation (PPV)

- Percutaneous tracheostomy

- Thoracentesis

- Pacemaker insertion

- Bronchoscopy

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Intercostal nerve block

Atraumatic pneumothorax may have an unknown etiology (primary) or arise as a complication of an underlying lung disease (secondary).

The possible causes of tension pneumothorax include all of the above.

Epidemiology

The actual incidence of tension pneumothorax is difficult to determine. Patients would have already received decompressive needle thoracotomy by the time they are transported to trauma centers. Patients who experience trauma tend to have an associated pneumothorax or tension pneumothorax 20% of the time. Severe chest trauma cases are associated with pneumothorax 50% of the time. The risk of traumatic pneumothorax depends on the size and mechanism of the injury. A review of military deaths from thoracic trauma suggests that up to 5% of combat casualties with thoracic trauma have tension pneumothorax at the time of death.[11][12]

Traumatic and tension pneumothorax cases are more common than spontaneous pneumothorax. Tension pneumothorax develops in 1% to 2% of cases initially presenting as idiopathic spontaneous pneumothorax. Meanwhile, the iatrogenic pneumothorax rate is rising in US hospitals because intensive care treatments have increasingly become dependent on PPV and CVC. Failed access at the initial vein, a subclavian vein approach, and PPV are all associated with increased pneumothorax risk.[13]

CVC-related pneumothorax risk increases when placed in the internal jugular or subclavian vein. The pneumothorax incidence after CVC is about 1% to 13% but can increase up to 30% in certain situations.[14] Ultrasound guidance reduces pneumothorax risk from CVC.

Iatrogenic pneumothorax usually causes substantial morbidity but rarely death. The incidence is 5 to 7 per 10,000 hospital admissions.

In a recent study, 95% of pneumothorax episodes were observed to be iatrogenic. Barotrauma secondary to mechanical ventilation was the cause in 69.6% of the cases, 41.1% of which progressed to tension pneumothorax. CVC insertion was responsible for 13.2% of cases.[15]

Pathophysiology

Tension pneumothorax is a direct complication of disrupting pleural cavity dynamics. Pleural cavity pressure is negative compared to lung pressure and atmospheric pressure. The lung tends to recoil inward but does not collapse because of the chest wall's outward recoil and the pressure gradient in the pleural cavity. Pneumothorax occurs when communication develops between the pleural cavity and the lung, causing air to enter the cavity. Pleural cavity pressure rises consequently, compressing the lung and reducing ventilation and oxygenation.[16]

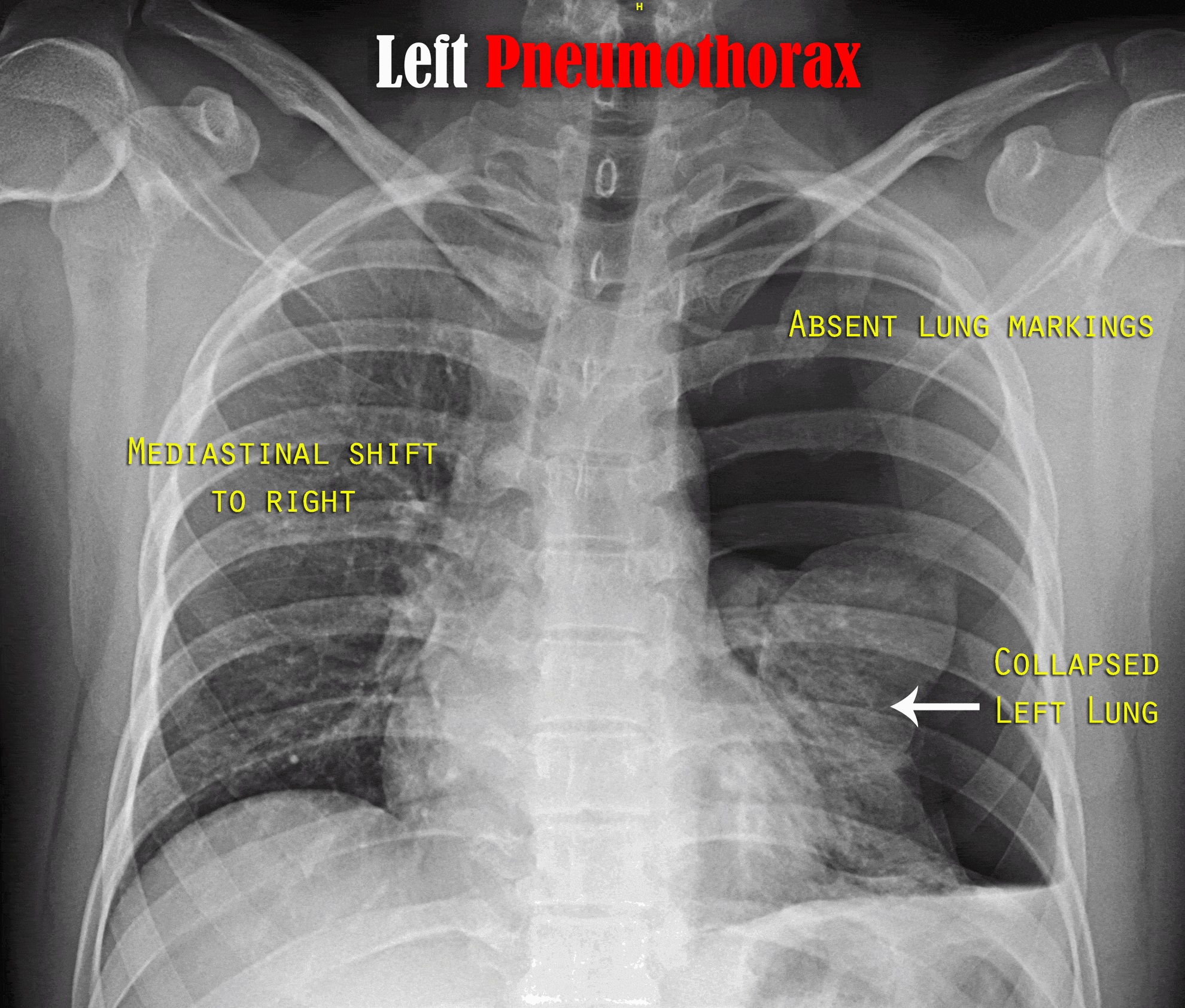

Tension pneumothorax occurs when the air accumulation is so sizable that it compresses the mediastinum and pushes it to the contralateral side (see Image. Left Tension Pneumothorax Radiograph). Compression of the superior vena cava impairs venous return and, consequently, cardiac output. Tracheal deviation results from mediastinal shifting.[17] The reduced cardiac output aggravates the hypoxemic state because it increases pulmonary vascular resistance. Circulatory collapse can produce acidosis. These complications can lead to cardiac arrest if tension pneumothorax is not managed in a timely fashion.[18][19]

History and Physical

Tension pneumothorax is an emergency. A quick, focused examination will reveal severe respiratory distress in a hypotensive patient. The affected hemithorax is enlarged and has no breath sounds. The trachea and mediastinum shift to the contralateral side. Air escaping after large-bore needle insertion in the 2nd anterior intercostal space (AICS) confirms the diagnosis.

History will reveal the cause of the tension pneumothorax. A history of recent trauma or receiving a medical procedure such as PPV or CVC is common. Some may have an underlying pulmonary condition like asthma or pneumonia. Besides shortness of breath, patients may complain of sharp, pleuritic chest pain radiating to the ipsilateral back or shoulder.

Other early physical findings include tachypnea, tachycardia, chest retractions, cyanosis, and jugular venous distension. The affected hemithorax will have reduced tactile fremitus and hyper-resonance. Subcutaneous emphysema may be seen in some cases.

Tension pneumothorax is a clinical diagnosis. Patients with this condition can easily decompensate and go into cardiac arrest if not managed immediately.[20] Unconscious patients without respirations or a pulse must be given immediate resuscitation regardless of the cause.

Evaluation

When in doubt about the diagnosis, the patient's status—whether stable or unstable—determines the next evaluation steps. A bedside ultrasound, if available, can confirm the diagnosis in the presence of hemodynamic instability. Patients should concurrently be stabilized, and the airway, breathing, and circulation assessed.

Ultrasound is 94% sensitive and 100% specific with a skilled operator. Bedside ultrasound can detect pneumothorax, which may be useful in unstable patients. Ultrasound findings include the absence of lung sliding and the presence of a lung point.[21][22][23][24][25] Needle decompression may still be performed if the diagnosis remains doubtful after performing a bedside ultrasound.

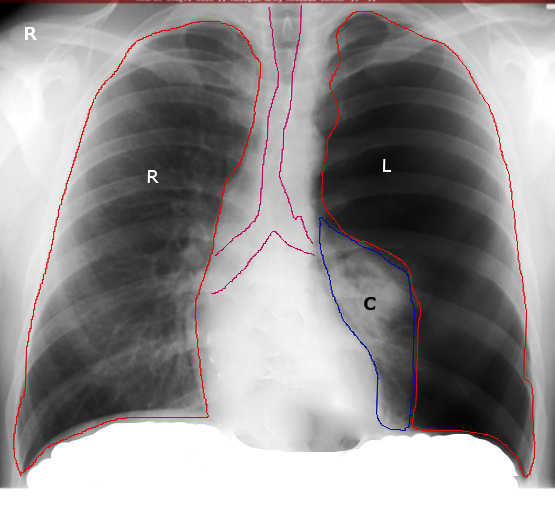

Radiographic evaluation is recommended when the patient is hemodynamically stable (see Image. Right Tension Pneumothorax Radiograph). The initial assessment involves a chest radiograph (CXR) to confirm the diagnosis.[26][27] CXR can demonstrate one or more of the following:

- A thin line representing the edge of the visceral pleura

- Effacement of lung markings distally to this line

- Complete ipsilateral lung collapse

- The mediastinal shift away from the pneumothorax in tension pneumothorax

- Subcutaneous emphysema

- Tracheal deviation to the contralateral side of tension pneumothorax

- Flattening of the hemidiaphragm on the ipsilateral side (tension pneumothorax)

A chest computed tomography (CT) can be done if the diagnosis is unclear on CXR. CT is the most reliable imaging study for diagnosing pneumothorax, though it is not recommended for routine use.

Treatment / Management

Tension pneumothorax can occur anywhere, and treatment depends on the circumstances at the time of onset. The condition is usually managed in the emergency department or the intensive care unit. Management strategies depend on the patient's hemodynamic stability. Airway, breathing, and circulation must be assessed in any patient presenting with chest trauma. Penetrating chest wounds must be covered with an airtight occlusive bandage and clean plastic sheeting.

Administration of 100% supplemental oxygen can help reduce the pneumothorax's size by decreasing the alveolar nitrogen partial pressure. Oxygen supplementation creates a diffusion gradient for nitrogen, thus accelerating pneumothorax resolution. Only 1.25% of the air is absorbed without oxygen in 24 hours. PPV should be avoided initially, as it may increase the tension pneumothorax's size. Patients may be placed on PPV after a chest tube is placed.[28][29](A1)

Immediate needle decompression must be performed without delay if the patient is hemodynamically unstable and clinical suspicion is high for pneumothorax. Needle placement is at the 2nd AICS in the midclavicular line above the rib with an angiocatheter. Needle decompression re-expands the collapsed lung. However, quick lung re-expansion increases the risk of pulmonary edema. A CXR is obtained, and CTT is performed following needle decompression.[30]

Serial CXRs can help assess pneumothorax resolution. The chest tube is removed when the lung has fully re-expanded, no air leaks are visible, and the patient has clinically improved.

Chest tubes are usually managed by experienced nurses, respiratory therapists, surgeons, and intensive care physicians. CTT suffices in 90% of pneumothorax cases. A video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or thoracotomy is performed on patients with pneumothoraces that do not resolve with CTT.[31][32][33][34](B2)

Patients requiring surgical intervention frequently have bilateral pneumothoraces, recurrent ipsilateral pneumothoraces, pulmonary decompression sickness, and more than 7 days of non-resolving air leaks. During VATS, the pneumothorax is treated with pleurodesis, which can be mechanical or chemical. Mechanical pleurodesis options include abrasive scratchpads, dry gauze, and parietal pleura stripping. Chemical pleurodesis is an alternative if the patient cannot tolerate mechanical pleurodesis. Chemical pleurodesis options include talc, minocycline, doxycycline, or tetracycline.

Recent studies show that pleurodesis can decrease the rate of pneumothorax recurrence. Mechanical pleurodesis reduces pneumothorax recurrence risk to less than 5%.[35][36](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of tension pneumothorax includes the following:

- Pulmonary embolism

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Acute aortic dissection

- Myocardial infarction

- Pneumonia

- Acute pericarditis

- Rib fracture

- Diaphragmatic injuries

The combined physical findings of severe respiratory distress, hypotension, an enlarged hemithorax, ipsilaterally absent breath sounds, and contralateral tracheal deviation will distinguish tension pneumothorax from the other conditions.

Prognosis

Tension pneumothorax arises from many causes and rapidly progresses to respiratory insufficiency, cardiovascular collapse, and death if not recognized and treated immediately. Diagnostic and management delays are associated with a poor prognosis.

Uncomplicated pneumothorax may recur within 6 months to 3 years, especially in smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).[37][38]

Ventilator-related tension pneumothorax has been found to have dire outcomes and frequently results in death.[39] By comparison, procedure-related tension pneumothorax has better outcomes than ventilator-related cases.[40]

Complications

Tension pneumothorax is potentially fatal. In patients who survive this condition, complications may arise from the lung injury itself or CTT, which include the following:

- Pneumopericardium

- Pneumoperitoneum

- Hemothorax

- Bronchopulmonary fistula

- Damage to the neurovascular bundle during CTT

- Pain and skin infection at the CTT site

- Empyema

- Pyopneumothorax

Timely diagnosis and management help improve outcomes in patients with tension pneumothorax.

Consultations

Needle decompression may be performed by the healthcare provider who detects the condition in a hypotensive patient with respiratory distress. After stabilizing the patient, one of the following specialists must be consulted for further evaluation and management:

- Thoracic surgeon

- Pulmonologist

- Interventional radiologist

- Intensivist

Early referral to these specialists can help refine management strategies and improve outcomes.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventing tension pneumothorax involves minimizing the risk factors that can lead to the development of this life-threatening condition. Patient education must include important preventive measures.

The first is to take precautions when performing high-risk activities. Using seatbelts and driving within the speed limit can prevent road mishaps. Other examples are adhering to workplace safety protocols and wearing protective gear during sports activities.

The second is treatment compliance in patients with chronic pulmonary disorders. Adequate control of medical conditions like COPD and asthma can reduce the likelihood of pneumothorax.

The third is practicing safe ascent for divers and pilots. Decompression sickness may be prevented by gradual ascent. Other measures that can prevent this condition are avoiding alcohol before a dive or flight, spacing multiple dives or flights adequately, avoiding air transport after a long, deep-sea dive, and physical fitness.[38]

The fourth is smoking cessation. Smoking is a risk factor for lung conditions that can predispose individuals to spontaneous pneumothorax.

Patients must also be advised to seek medical attention immediately for new or worsening symptoms, especially if trauma-related.

While some occurrences of tension pneumothorax may be unpredictable, practicing these preventive measures can significantly reduce the risk of developing tension pneumothorax and its complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

The following are the key points in managing tension pneumothorax:

- Tension pneumothorax is a clinical diagnosis. The condition may arise from traumatic and atraumatic causes and prehospital and in-hospital settings.

- If a patient is hemodynamically unstable and a tension pneumothorax is likely, needle decompression must be performed immediately, followed by CTT.

- If the patient is stable, diagnostic imaging like CXR can be obtained before treatment.

- Patients with pulmonary conditions predisposing them to high peak inspiratory pressures are at greater risk of tension pneumothorax.

- CTT suffices for managing most pneumothorax cases. Other surgical treatments like VATS with pleurodesis may be necessary in others.

Quick diagnosis and management can prevent significant morbidity and mortality from this condition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Tension pneumothorax diagnosis and management require a high level of cooperation among interprofessional healthcare team members. The following providers comprise this team:

- First responders: These providers are the first to identify the condition and perform needle decompression. The circumstances determine which providers are the first to respond to the crisis. At the prehospital level, it may be the emergency medical technicians (EMTs) or physicians designated as first responders. At the emergency department, it is the emergency medicine physician. In the intensive care unit, it is the intensivist.

- Nursing staff: Different nurses may be assigned to perform intravenous catheterization, initiate cardiac monitoring, and prepare the emergency cart while stabilizing a patient with tension pneumothorax. Once the patient is stable, nurses take charge of administering medications, coordinating care, and reinforcing patient education.

- Radiologist: This provider evaluates the extent of lung collapse or other associated injuries through imaging studies. The radiologist's role is critical to determining the definitive management of tension pneumothorax.

- Respiratory therapist: These providers assist in administering respiratory interventions like oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation to patients with tension pneumothorax.

- Trauma or thoracic surgeon: CTT may be performed by an emergency physician, trauma surgeon, or thoracic specialist. If pneumothorax does not resolve with CTT, a trauma or thoracic surgeon can perform another surgical procedure like VATS to correct the problem.

- Pulmonologist: This specialist renders care to patients on ventilatory support and manages the pulmonary conditions that may have caused the tension pneumothorax.

The collaboration and coordination among these interprofessional team members are crucial in the prompt recognition, immediate intervention, and comprehensive care of patients with tension pneumothorax.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Left-Sided Tension Pneumothorax Radiograph. This image shows a collapsed left lung and mediastinal contents shifting to the right.

Karthik Easvur, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Rojas R, Wasserberger J, Balasubramaniam S. Unsuspected tension pneumothorax as a hidden cause of unsuccessful resuscitation. Annals of emergency medicine. 1983 Jun:12(6):411-2 [PubMed PMID: 6859647]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceATLS Subcommittee, American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma, International ATLS working group. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS®): the ninth edition. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2013 May:74(5):1363-6. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828b82f5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23609291]

Roberts DJ, Leigh-Smith S, Faris PD, Ball CG, Robertson HL, Blackmore C, Dixon E, Kirkpatrick AW, Kortbeek JB, Stelfox HT. Clinical manifestations of tension pneumothorax: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic reviews. 2014 Jan 4:3():3. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-3. Epub 2014 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 24387082]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCameron PA, Flett K, Kaan E, Atkin C, Dziukas L. Helicopter retrieval of primary trauma patients by a paramedic helicopter service. The Australian and New Zealand journal of surgery. 1993 Oct:63(10):790-7 [PubMed PMID: 8274122]

Coats TJ, Wilson AW, Xeropotamous N. Pre-hospital management of patients with severe thoracic injury. Injury. 1995 Nov:26(9):581-5 [PubMed PMID: 8550162]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEckstein M, Suyehara D. Needle thoracostomy in the prehospital setting. Prehospital emergency care. 1998 Apr-Jun:2(2):132-5 [PubMed PMID: 9709333]

Diaz R, Heller D. Barotrauma and Mechanical Ventilation. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424810]

Melton LJ 3rd, Hepper NG, Offord KP. Incidence of spontaneous pneumothorax in Olmsted County, Minnesota: 1950 to 1974. The American review of respiratory disease. 1979 Dec:120(6):1379-82 [PubMed PMID: 517861]

Gupta D, Hansell A, Nichols T, Duong T, Ayres JG, Strachan D. Epidemiology of pneumothorax in England. Thorax. 2000 Aug:55(8):666-71 [PubMed PMID: 10899243]

Sharma A, Jindal P. Principles of diagnosis and management of traumatic pneumothorax. Journal of emergencies, trauma, and shock. 2008 Jan:1(1):34-41. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.41789. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19561940]

Toffel M, Pin M, Ludwig C. [Thoracic Surgical Aspects of Seriously Injured Patients]. Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie. 2020 Feb:145(1):108-120. doi: 10.1055/a-0903-1461. Epub 2020 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 32097982]

McPherson JJ, Feigin DS, Bellamy RF. Prevalence of tension pneumothorax in fatally wounded combat casualties. The Journal of trauma. 2006 Mar:60(3):573-8 [PubMed PMID: 16531856]

Vinson DR, Ballard DW, Hance LG, Stevenson MD, Clague VA, Rauchwerger AS, Reed ME, Mark DG, Kaiser Permanente CREST Network Investigators. Pneumothorax is a rare complication of thoracic central venous catheterization in community EDs. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2015 Jan:33(1):60-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.10.020. Epub 2014 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 25455050]

Tsotsolis N, Tsirgogianni K, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, Baka S, Papaiwannou A, Karavergou A, Rapti A, Trakada G, Katsikogiannis N, Tsakiridis K, Karapantzos I, Karapantzou C, Barbetakis N, Zissimopoulos A, Kuhajda I, Andjelkovic D, Zarogoulidis K, Zarogoulidis P. Pneumothorax as a complication of central venous catheter insertion. Annals of translational medicine. 2015 Mar:3(3):40. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.02.11. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25815301]

El-Nawawy AA, Al-Halawany AS, Antonios MA, Newegy RG. Prevalence and risk factors of pneumothorax among patients admitted to a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Indian journal of critical care medicine : peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2016 Aug:20(8):453-8. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.188191. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27630456]

Roberts DJ, Leigh-Smith S, Faris PD, Blackmore C, Ball CG, Robertson HL, Dixon E, James MT, Kirkpatrick AW, Kortbeek JB, Stelfox HT. Clinical Presentation of Patients With Tension Pneumothorax: A Systematic Review. Annals of surgery. 2015 Jun:261(6):1068-78. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001073. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25563887]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMartin M, Satterly S, Inaba K, Blair K. Does needle thoracostomy provide adequate and effective decompression of tension pneumothorax? The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2012 Dec:73(6):1412-7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825ac511. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22902737]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBarton ED, Rhee P, Hutton KC, Rosen P. The pathophysiology of tension pneumothorax in ventilated swine. The Journal of emergency medicine. 1997 Mar-Apr:15(2):147-53 [PubMed PMID: 9144053]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNelson D, Porta C, Satterly S, Blair K, Johnson E, Inaba K, Martin M. Physiology and cardiovascular effect of severe tension pneumothorax in a porcine model. The Journal of surgical research. 2013 Sep:184(1):450-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.05.057. Epub 2013 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 23764307]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLight RW. Pleural diseases. Disease-a-month : DM. 1992 May:38(5):266-331 [PubMed PMID: 1572232]

Gordon R. The deep sulcus sign. Radiology. 1980 Jul:136(1):25-7 [PubMed PMID: 7384513]

DORNHORST AC, PIERCE JW. Pulmonary collapse and consolidation; the role of collapse in the production of lung field shadows and the significance of segments in inflammatory lung disease. The Journal of the Faculty of Radiologists. Faculty of Radiologists (Great Britain). 1954 Apr:5(4):276-81 [PubMed PMID: 24543591]

Zhang M, Liu ZH, Yang JX, Gan JX, Xu SW, You XD, Jiang GY. Rapid detection of pneumothorax by ultrasonography in patients with multiple trauma. Critical care (London, England). 2006:10(4):R112 [PubMed PMID: 16882338]

Soldati G, Iacconi P. The validity of the use of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of spontaneous and traumatic pneumothorax. The Journal of trauma. 2001 Aug:51(2):423 [PubMed PMID: 11493817]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShostak E, Brylka D, Krepp J, Pua B, Sanders A. Bedside sonography for detection of postprocedure pneumothorax. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2013 Jun:32(6):1003-9. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.6.1003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23716522]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZarogoulidis P, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, Porpodis K, Lampaki S, Papaiwannou A, Katsikogiannis N, Zaric B, Branislav P, Secen N, Dryllis G, Machairiotis N, Rapti A, Zarogoulidis K. Pneumothorax: from definition to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of thoracic disease. 2014 Oct:6(Suppl 4):S372-6. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.09.24. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25337391]

Arao K, Mase T, Nakai M, Sekiguchi H, Abe Y, Kuroudu N, Oobayashi O. Concomitant Spontaneous Tension Pneumothorax and Acute Myocardial Infarction. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2019 Apr 15:58(8):1131-1135. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.1422-18. Epub 2019 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 30626814]

Vallee P, Sullivan M, Richardson H, Bivins B, Tomlanovich M. Sequential treatment of a simple pneumothorax. Annals of emergency medicine. 1988 Sep:17(9):936-42 [PubMed PMID: 3137850]

Henry M, Arnold T, Harvey J, Pleural Diseases Group, Standards of Care Committee, British Thoracic Society. BTS guidelines for the management of spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorax. 2003 May:58 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):ii39-52 [PubMed PMID: 12728149]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDominguez KM, Ekeh AP, Tchorz KM, Woods RJ, Walusimbi MS, Saxe JM, McCarthy MC. Is routine tube thoracostomy necessary after prehospital needle decompression for tension pneumothorax? American journal of surgery. 2013 Mar:205(3):329-32; discussion 332. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.01.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23414956]

Terada T, Nishimura T, Uchida K, Hagawa N, Esaki M, Mizobata Y. How emergency physicians choose chest tube size for traumatic pneumothorax or hemothorax: a comparison between 28Fr and smaller tube. Nagoya journal of medical science. 2020 Feb:82(1):59-68. doi: 10.18999/nagjms.82.1.59. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32273633]

Chen KC, Chen PH, Chen JS. New options for pneumothorax management. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2020 Jun:14(6):587-591. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2020.1740090. Epub 2020 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 32174202]

Eguchi M, Abe T, Tedokon Y, Miyagi M, Kawamoto H, Nakasone Y. [Traumatic Intercostal Lung Hernia Repaired by Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery;Report of a Case]. Kyobu geka. The Japanese journal of thoracic surgery. 2019 Nov:72(12):1038-1041 [PubMed PMID: 31701918]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnson G. Traumatic pneumothorax: is a chest drain always necessary? Journal of accident & emergency medicine. 1996 May:13(3):173-4 [PubMed PMID: 8733651]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePaydar S, Ghahramani Z, Ghoddusi Johari H, Khezri S, Ziaeian B, Ghayyoumi MA, Fallahi MJ, Niakan MH, Sabetian G, Abbasi HR, Bolandparvaz S. Tube Thoracostomy (Chest Tube) Removal in Traumatic Patients: What Do We Know? What Can We Do? Bulletin of emergency and trauma. 2015 Apr:3(2):37-40 [PubMed PMID: 27162900]

van den Brande P, Staelens I. Chemical pleurodesis in primary spontaneous pneumothorax. The Thoracic and cardiovascular surgeon. 1989 Jun:37(3):180-2 [PubMed PMID: 2763278]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHuang TW, Lee SC, Cheng YL, Tzao C, Hsu HH, Chang H, Chen JC. Contralateral recurrence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Chest. 2007 Oct:132(4):1146-50 [PubMed PMID: 17550937]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBritish Thoracic Society Fitness to Dive Group, Subgroup of the British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. British Thoracic Society guidelines on respiratory aspects of fitness for diving. Thorax. 2003 Jan:58(1):3-13 [PubMed PMID: 12511710]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHsu CW, Sun SF, Lee DL, Chu KA, Lin HS. Clinical characteristics, hospital outcome and prognostic factors of patients with ventilator-related pneumothorax. Minerva anestesiologica. 2014 Jan:80(1):29-38 [PubMed PMID: 24122035]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChen KY, Jerng JS, Liao WY, Ding LW, Kuo LC, Wang JY, Yang PC. Pneumothorax in the ICU: patient outcomes and prognostic factors. Chest. 2002 Aug:122(2):678-83 [PubMed PMID: 12171850]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence