Introduction

The bladder is a subperitoneal, hollow muscular organ that acts as a reservoir for urine. The bladder is located in the lesser pelvis when empty and extends into the abdominal cavity when full. In children, the bladder is located in the abdomen and does not completely descend into the pelvis until puberty. The bladder is a distensible organ and is typically able to hold up to 500 milliliters of urine.

The size of the pediatric bladder can be predicted by the following: (Age + 2) x 30 mL.

The bladder is situated just posterior to the pubic symphysis. Posteriorly, the anterior wall of the vagina sits behind the bladder in females. In males, the rectum is located posterior to the bladder. Inferiorly, the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm support the bladder. The bladder is a relatively free organ in the subcutaneous fat of the sub peritoneum except for some fixed ligamentous connections at the bladder neck. The superior and part of the posterior surfaces of the bladder are covered by peritoneum. The inferior portion and inferolateral sides of the bladder are covered by endopelvic fascia.

Anatomically, the bladder is contiguous with the ureters above and the urethra below. It is divided into four anatomical parts: the apex or dome, body, fundus, and neck. The apex is the anterosuperior part of the bladder that points towards the abdominal wall. The fundus, or base, is the posteroinferior part of the bladder. The body is the large area situated between the apex and the fundus. The neck of the bladder is the constricted part of the bladder that leads to the urethra.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The bladder functions as a reservoir and active excretory organ for urine. Urine excreted by the kidneys passes through the ureters and the ureterovesical junction into the bladder. As the bladder fills with urine, sensory nerves traveling back to the central nervous system communicate with efferent somatic and autonomic nerves to control the release of urine through stimulation of the detrusor (bladder) muscle with simultaneous relaxation of the internal and external urethral sphincters.

Embryology

The bladder is mostly a mesodermal organ but does contain some endoderm as well. Between weeks 4 to 7 of fetal development, the cloaca divides into the urogenital sinus ventrally, and the anal canal dorsally. The urogenital sinus is continuous with the allantois anteriorly. The base of the allantois expands and develops into the bladder while its anterior portion gives rise to the urachus. The urachus later develops into a fibrous cord, the median umbilical ligament.[1]

Through mechanisms not clearly explained, the mesonephric ducts and ureteric buds connect to the posterior bladder wall and form a part of the trigone. The mesonephric ducts also migrate ventrally and come together to give rise to the urethra.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The superior and inferior vesicle arteries provide the blood supply to the bladder. These are indirect branches of the internal iliac arteries. The bladder also receives some of its blood supply from the obturator artery and the inferior gluteal artery. In some cases, the inferior vesicle artery may be a branch of the internal pudendal artery.

Blood is drained from the bladder via the vesical venous plexus that empties into the internal iliac vein. Lymphatics are drained via various lymph nodes associated with the veins in the area, with most of the drainage occurring via the external iliac lymph nodes.[2]

Nerves

The bladder receives its innervation through a network of parasympathetic, sympathetic and somatic nerve fibers. Parasympathetic fibers arise from sacral spinal nerves (S2-S4) that coalesce to form the pelvic splanchnic nerves. Sympathetic control arises from the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spinal levels (T10-L2) in the form of the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses and nerves. The pudendal nerve (S2-S4), a branch of the sacral plexus, provides voluntary somatic control to the striated muscles of the external urethral sphincter.[3] These fibers originate in the ventral horn of the sacral spinal cord which is called Onuf's nucleus.

Mechanoreceptors in the bladder wall respond to the stretch of the muscle with distension. These receptors send sensory information to the central nervous system (CNS) via general visceral afferent (GVA) fibers of the hypogastric and pelvic splanchnic nerves. Sensory information from the superior bladder wall follows the path of the sympathetic innervation, while that from the inferior part of the bladder follows the parasympathetic nerves. The speed of the stimulus sent back to the CNS corresponds to the degree of distension of the bladder, such that a mildly distended bladder will generate slow stimuli, while a fully distended bladder will increase the speed of the stimuli to the CNS.[3]

The micturition center, which regulates the process of bladder filling and voiding is located in the pons of the brainstem (pontine micturition center). In general, the parasympathetic response stimulates bladder emptying, and the sympathetic response promotes bladder filling.[3]

Parasympathetic nerves stimulate the detrusor muscle to contract and the internal urethral sphincter to relax to allow for micturition. Sympathetic stimulation allows for relaxation or filling of the detrusor muscle and constriction of the internal sphincter. Local spinal reflexes primarily regulate the process of bladder filling; that, of voiding, however, requires action from the pontine micturition center in the brainstem.[3][4][3]

As an empty bladder fills with urine, mechanoreceptors detect the stretch in the wall of the detrusor muscle and send slow afferent fibers back to the spinal cord. This stimulates the sympathetic response on the detrusor and internal sphincter via the hypogastric nerves, causing them to relax and constrict, respectively. The parasympathetic response is inhibited at this time. Signals from the pudendal nerve to the external urethral sphincter are also stimulated to keep the external urethra contracted and closed. When the bladder becomes fully distended, sensory fibers travel to the pontine micturition center, stimulating the parasympathetic response and inhibiting the sympathetic tone to allow for contraction of the detrusor muscle and relaxation of the internal sphincter. Throughout this, somatic innervation to the external urethral sphincter remains tonically active to keep the sphincter contracted. When voiding is appropriate, activity from the pudendal nerve is inhibited to allow relaxation of the sphincter and the release of urine. Stimuli sent to the cortex during the filling process also play a role in voiding. The cortex processes emotional, sensory and social stimuli and acts on cells in the PMC and the periaqueductal gray (PAG) to prevent voiding until the appropriate time.[5]

Muscles

The detrusor muscle is the primary muscle of the bladder. It is divided into the body, fundus, apex or dome, and neck. The detrusor muscle is smooth muscle composed of transitional epithelium or urothelium. Transitional epithelium is stratified epithelium, and its cells change shape depending on the volume of urine in the bladder. When the bladder is empty, the cells of the urothelium are round and large. As the bladder fills with urine, the cells transition into flatter cells to accommodate a greater volume of urine. The detrusor muscle wall contains muscarinic (M3) receptors regulated under parasympathetic control. It also contains beta-adrenergic receptors for sympathetic regulation.[2]

The internal urethral sphincter is found in the neck of the bladder leading into the urethra. This is also composed of smooth muscle cells and contains alpha-adrenergic receptors for sympathetic regulation. Stimulation of this receptor causes constriction to allow for bladder filling, and disinhibition causes relaxation for voiding.[4]

The external urethral sphincter is composed of striated skeletal muscle. Nicotinic receptors are found on these cells and are under the control of the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve contains somatic nerve fibers that constantly fire to keep the sphincter contracted until the appropriate time to void. During toilet-training, humans learn to voluntarily control the regulation of the external urethral sphincter to prevent voiding at inappropriate occasions.[4]

Physiologic Variants

The development of voluntary control of micturition is a highly complex process that involves many levels of the brain, brainstem, spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system. Infants and children lack voluntary control of urination until their nervous system develops, typically between 2 to 4 years of age. Prior to this, voiding occurs via spinal reflexes activated when the bladder reaches a specific volume.[3]

Surgical Considerations

Urinary dysfunction after surgery for colorectal cancer or gynecological surgeries is a well-known, postoperative complication secondary to damage of the pelvic autonomic plexus. High complication rates associated with surgeries such as abdominoperineal (close to 50%) or low anterior resections (15% to 20%) have led to the development of newer surgical techniques that have decreased complication rates. Variations in pelvic anatomy, however, continue to make urinary dysfunction a complication, not only of colorectal surgery, but gynecological, prostatic and other pelvic surgeries. Patients present with a number of symptoms, including but not limited to urinary urgency, stress incontinence, and impaired detrusor contractility. Erectile dysfunction secondary to damage to the pudendal nerve can also occur.[4]

Clinical Significance

The bladder is the cause of many medical conditions that present to various clinicians in the medical field. Bacterial infections are one of the most common causes of urinary tract infections. More than 7 million office visits in the United States are due to urinary tract infections (UTI). UTIs also result in more than 1 million emergency department visits. UTIs occur in both men and women, but women are at greater risk due to their shorter urethra. The increase in antibiotic resistance has also increased rates of pyelonephritis.[6] Typical causes of UTIs include incomplete bladder emptying, vesicoureteral reflux, urinary stones, neurogenic bladder, and poor personal hygienic practices.

Incontinence is also a common presenting patient complaint. It mostly presents in the post-menopausal population; however, it can occur as a post-surgical complication or after pregnancy. Prostatic hyperplasia or cancer can also result in incontinence or urinary retention. There are various forms of incontinence. Some of the most common causes include urge, stress, overflow, mixed, and functional incontinence. Urge incontinence occurs secondary to overactive detrusor muscle contractility. Stress incontinence is caused by weakening of the pelvic floor muscles and/or fascia and increased intra-abdominal pressure. Muscles of the pelvic floor play a role in keeping the sphincters contracted. Loss of their support results in increased urethral mobility with a resultant uncontrolled urinary loss. Overflow incontinence occurs in those with bladder outlet dysfunction that prevents complete bladder emptying. This is frequently seen in those with prostatic hyperplasia, impaired detrusor contractility or narrowing of the urethra such as from stricture disease, all of which can prevent the bladder from completely emptying. As a result, the bladder overfills with urine, resulting in a continuous leakage or dribbling of urine. Functional incontinence occurs when one recognizes the need to void but is not able to make it to the bathroom. This can be caused by many reasons such as immobility, dementia, psychological disorders (anxiety, depression, among others), or lack of access to a bathroom.[7]

Other Issues

Autonomic dysreflexia, a potentially life-threatening condition in patients with spinal cord injuries at or above T6, is caused by bladder issues (usually a blocked Foley catheter or overdistension) about 85% of the time. Typically, this disorder presents as an intense headache along with bradycardia and severe hypertension. Above the injury, there is vasodilation, but below the level of injury, the skin will feel cold and clammy. Treatment requires immediate relief of the triggering event, usually changing the Foley catheter.

Media

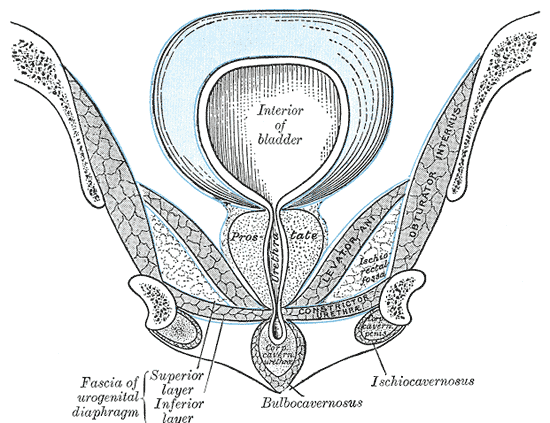

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor, Interior of bladder, Anal Canal, Diaphragmatic part of pelvic fascia; Superior Layer and Inferior Layer, Tendinous Arch, Fascia Endopelvic, Vesicula Seminalis, Ductus Deferens, Rectovesical layer, Alcock's Canal, Obturator Internus

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

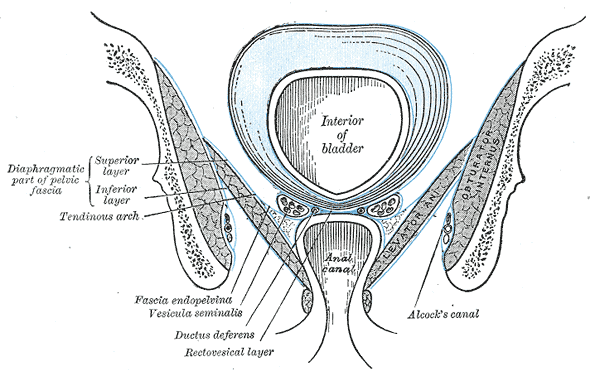

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Median Sagittal Section of Male Pelvis Anatomy. Anatomy includes pelvis, sacrum, peritoneum, vesical layer, fascia of urogenital diaphragm, superior and inferior layer, bladder, prostate, symphysis pubis, rectum, anal canal, corpus cavernosum penis and urethra, bulb, scrotum, urogenital diaphragm, Colles fascia, transversus perinei superficialis, rectal layer, vesicula seminalis, rectovesical layer, and capsule of prostate.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

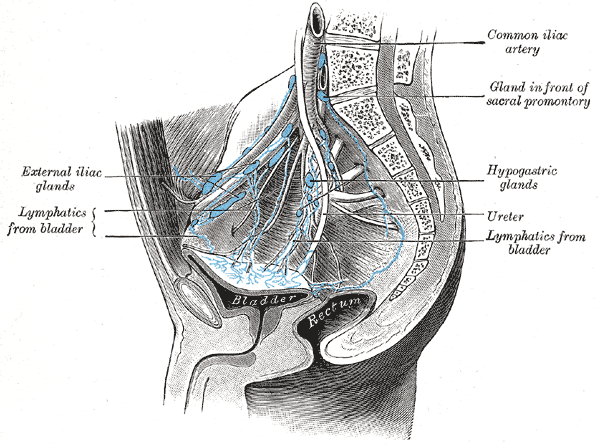

(Click Image to Enlarge)

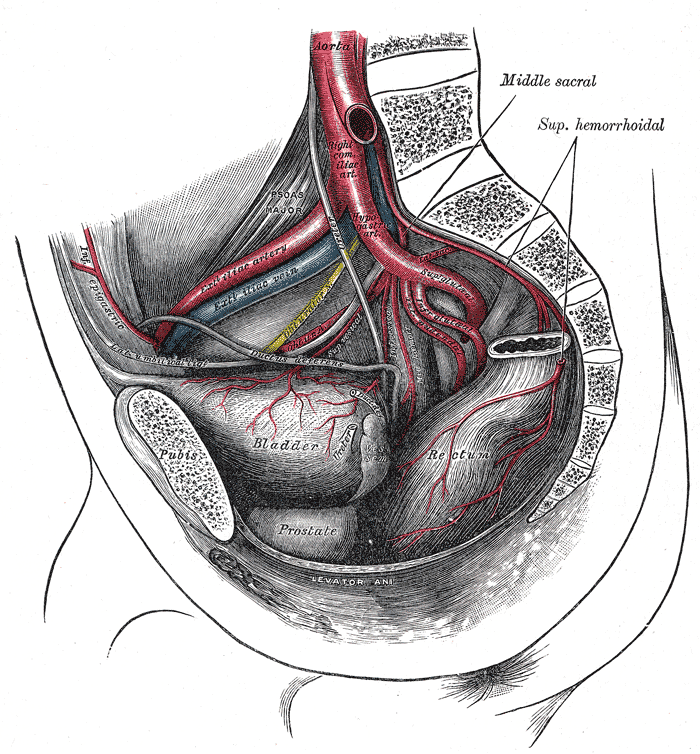

(Click Image to Enlarge)

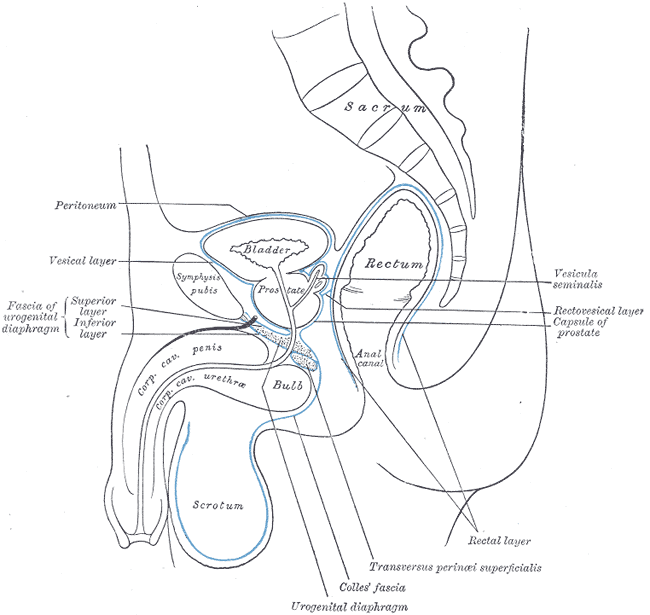

Arteries of the Pelvis, Male Abdomen. The right common iliac artery, hypogastric artery, superior gluteal artery, infra gluteal artery, inferior gluteal artery, external Iliac vein, external iliac artery, bladder, prostate, and rectum are seen in the illustration.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

DeSouza KR, Saha M, Carpenter AR, Scott M, McHugh KM. Analysis of the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway in normal and abnormal bladder development. PloS one. 2013:8(1):e53675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053675. Epub 2013 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 23308271]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSam P, Nassereddin A, LaGrange CA. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Bladder Detrusor Muscle. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489195]

Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, de Groat WC. The neural control of micturition. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2008 Jun:9(6):453-66. doi: 10.1038/nrn2401. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18490916]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSam P, Jiang J, Leslie SW, LaGrange CA. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sphincter Urethrae. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494045]

de Groat WC, Griffiths D, Yoshimura N. Neural control of the lower urinary tract. Comprehensive Physiology. 2015 Jan:5(1):327-96. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130056. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25589273]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSimmering JE, Tang F, Cavanaugh JE, Polgreen LA, Polgreen PM. The Increase in Hospitalizations for Urinary Tract Infections and the Associated Costs in the United States, 1998-2011. Open forum infectious diseases. 2017 Winter:4(1):ofw281. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw281. Epub 2017 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 28480273]

Aoki Y, Brown HW, Brubaker L, Cornu JN, Daly JO, Cartwright R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2017 Jul 6:3():17042. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.42. Epub 2017 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 28681849]