Introduction

Lateral ankle instability is a complex condition that can, at times, prove difficult to evaluate and treat for general practitioners. The difficulty in evaluation and treatment is due in part to the ankle complex is composed of three joints: talocrural, subtalar, and tibiofibular syndesmosis. All three joints function in conjunction to allow complex motions of the ankle joint. The main contributors to the stability of the ankle joint are the articular surfaces, the ligamentous complex and the musculature - which allows for the dynamic stabilization of the joints. The lateral ankle is comprised of the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) and the posterior talofibular ligaments (PTFL). The anterior talofibular ligament originates from the along the anterior colliculus of the lateral malleolus and inserts on the lateral talar articular facet, with its course running in 45-90 degrees to the longitudinal axis of the tibia. The primary function of the ATFL is to resist inversion in plantarflexion and anterolateral translation of the talus in the mortise. The calcaneal fibular ligament originates from the anterior border of the fibula approximately 9mm proximal to the distal tip and inserts on the calcaneus approximately 13mm distal to the subtalar joint and rooted to the peroneal tendon sheath. The CFL crosses both the subtalar joint and the ankle joint. The primary functions of the CFL are to resist inversion in neutral and dorsiflexed position and also restrains subtalar inversion, which limits talar tilt within the mortise. Lastly, the posterior talofibular ligament is the strongest of the lateral ligaments but only plays a supplementary role in ankle stability. The PTFL originates on the posterior border of the fibula and inserts on the posterolateral tubercle of the talus and runs perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the tibia. Of the three ligaments (ATFL, CFL, and PTFL) only the CFL ligament is extracapsular to the ankle joint.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Lateral ligament instability can result from either of two means; functional or mechanical instability. Mechanical instability arises either via an acute injury or chronic repetitive stress resulting in attenuation and alteration of the mechanical structures of the ligaments. The most common mechanism of injury in lateral ankle sprain occurs with a plantar-flexory force on an inverted ankle as the body moves over the foot. The ATFL is the most commonly injured ligament followed by the CFL, and then the PTFL [1]. Ligaments often heal in an elongated position which can lead to plastic deformation, which further reduces the ability to provide restraint. Functional instability is the feeling of ankle instability or recurrent, symptomatic ankle sprains due to proprioceptive deficits. Lateral ankle instability can also be caused by hereditary ligamentous laxity that is associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome and Turner’s syndrome.

Epidemiology

40% of all athletic injuries are ankle sprains, making ankle sprains the most commonly sustained injury during sporting events[2]. Over 50% of basketball injuries and almost 30% of soccer injuries can be attributed directly to ankle injuries[3]. Over 10% of the emergency room visits in the United States are due to ankle sprains with an incidence of 30,000 per day[4]. 75% of ankle injuries involve the lateral ankle with an equal distribution between male and females. Some literature has reported a 25% higher rate of grade I sprains in females compared to males, and a higher predisposition to suffering future sprains once having sustained an ankle sprain [5][6][7][8]. 90% of all ankle sprains involve the ATFL, while 50-75% of the time the CFL is engaged, and only 10% of the time is the PTFL involved[9][10][11][12]. 55-72% of patients who sustain a lateral ankle sprain suffer residual symptoms. In the USA the estimated incidence rate of ankle sprains in the general population presenting to emergency departments is 2.15 per 1,000 person- per year. The incidence of ankle sprains in the military has been reported to be up to 27-fold higher than in the general population. [13]

Pathophysiology

As previously stated, ankle sprains are a common injury, which can lead to ligament attenuation of the lateral ankle and can further propagate ankle instability. An injury to the lateral ankle can lead to both functional and mechanical instability of the ankle. Lateral ankle instability can also be caused by hereditary ligamentous conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome and Turner’s syndrome.

History and Physical

A thorough history can point practitioners in the right direction when evaluating a patient with ankle instability or pain. A history of recurrent or recent ankle sprains can raise a red flag to guide a physician for a more in-depth examination of the ankle and its stability. Patients will often report repeated episodes of the ankle “giving way” on uneven terrain or a feeling of looseness and may be especially mindful of specific activities in which they are aware they may have the potential for injuries. Pain itself can also be a complaint, though generally not the chief complaint.

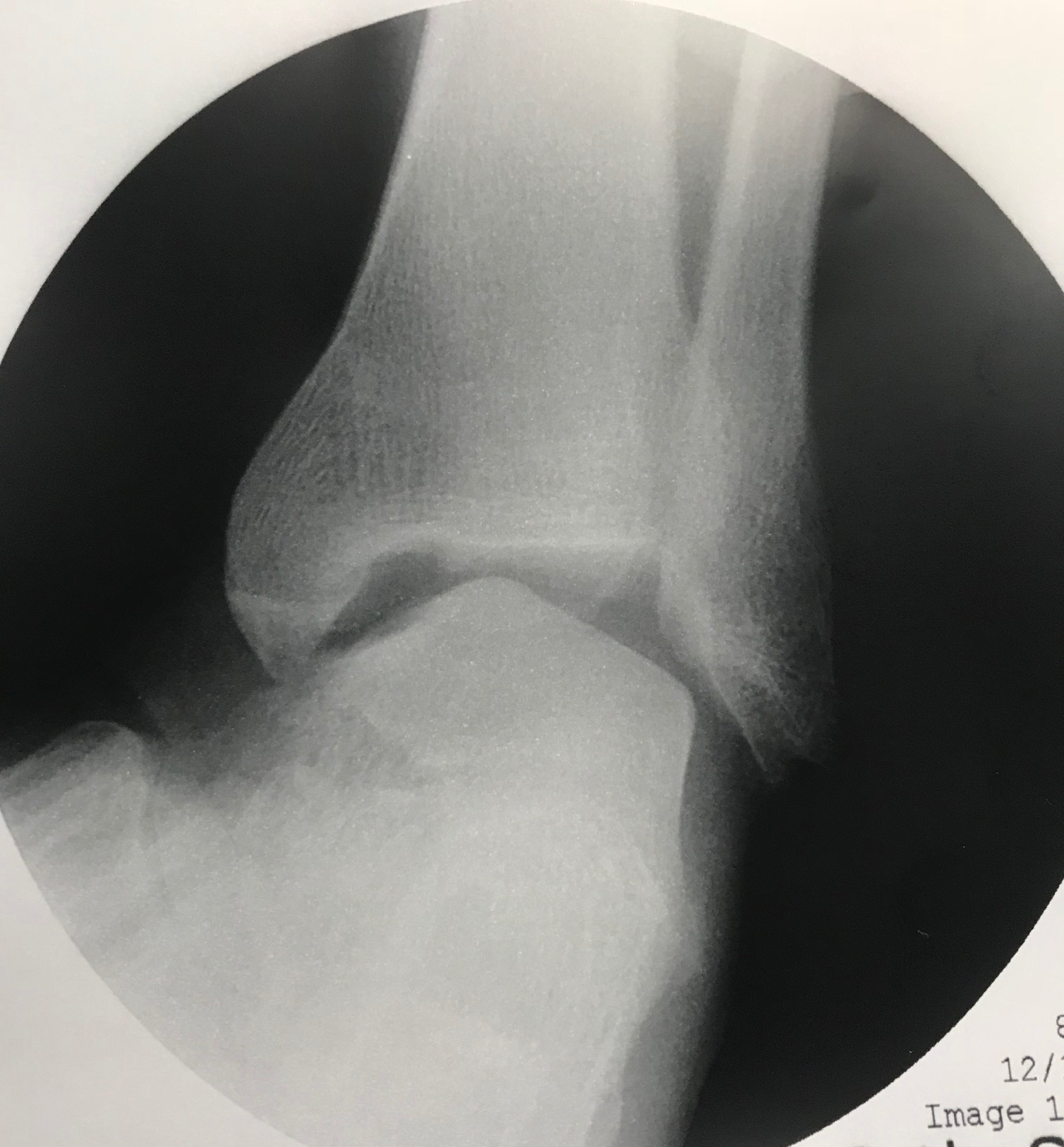

Physical of examination of the foot and ankle when approaching ankle instability should always include assessment of alignment, as individual factors such as cavus or varus may predispose patient to recurrent instability. Hypermobility should also be a consideration when initially evaluating patients as laxity may predispose to further injury. The range of motion and strength are also crucial to a full examination, especially when compared to the contralateral extremity. Stress examinations including the talar tilt and anterior drawer test individually evaluate the lateral ankle ligaments. The Anterior drawer should be performed with the foot in 20 plantarflexion, and then compared to the contralateral extremity. A shift during the anterior drawer test of more than 8mm is considered pathological. The talar tilt examination assesses CFL integrity, and a value of greater than 10 degrees or more than 5 degrees compared to the contralateral side is considered pathological when viewed on a radiograph. Physiological talar tilt can range from 5 to 23 degrees.

Evaluation

Evaluation of lateral instability consists of the history, and physical described previously but also includes radiographs of the ankle to assess for syndesmosis widening, foot or ankle deformities which may predispose patients to instability. Stress radiographs such as with the anterior drawer test or talar tilt test are also essential to evaluate for structural abnormalities. Patients with mechanical instability will display radiological evidence, patients with functional instability may have a negative anterior drawer or talar tilt tests. MRI can be useful to evaluate the lateral ankle complex, and it can also identify concomitant pathologies such as talar dome osteochondral defects, peroneal tendon pathology and can be of assistance in surgical planning. Evaluation can consist of the staging of the injury to the lateral ankle, and there have been many classification descriptions over the years.

Anatomic

- Grade I - stretching of the lateral ligament complex

- Grade II - Partial tearing of one or several of the ligaments in the lateral ligament complex

- Grade III - Complete rupture of the lateral ligament complex.

Functional

- Grade I - the patient can fully bear weight and walk.

- Grade II - patient walks with a noticeable limp.

- Grade III - patient unable to walk

Stage I - ATFL involvement - microscopic tears

Stage II - ATFL involvement predominantly with CFL injury

Stage III - ATFL and CFL involvement with complete disruption of both ligaments and gross laxity noted upon examination.

Treatment / Management

Conservative treatment of lateral ankle instability consists of early functional rehabilitation; including rest, ice, elevation, compression, initial range of motion, progressive weight-bearing guided by symptom tolerance, and physical therapy. Even with proper functional rehabilitation 10 to 40% of patients will go on to develop chronic ankle instability following acute ankle sprains. Multiple studies have been published which show both the benefits of conservative therapy as well as surgical treatment for cases that do not adequately respond to conservative treatment.

There have been more than 70 different operative techniques described in the literature for correcting ankle instability, and can be divided into three main categories; anatomic, non-anatomic, and anatomic augmented tenodesis reconstruction.

Anatomic reconstruction consists of the Brostrom procedure, which includes direct repair of the ATFL in pants over vest fashion, this reduces any redundancy due to ligamentous laxity and can be used for completely torn ligaments. The Brostrom procedure has been modified and can include the use of the extensor retinaculum to increase the efficacy of the repair.

Non-anatomic reconstructions are aptly named because they do not repair or recreate the native lateral ligament complex. The use of the peroneus brevis tendon in the Evans and Christman-Snook procedure recreates stability to the lateral ankle.

Anatomic augmented tenodesis reconstructions typically combine a traditional Brostrom procedure with either autograft or allograft tissue and can be accomplished via suture anchors or interference screws.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of lateral ankle instability includes other conditions which can cause pain and weakness to the lateral ankle including:

- Hereditary ligamentous laxity disorders (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan's syndrome, and Turner's syndrome)

- Acute ankle injury/instability

- Chronic ankle instability

- Fracture

- Sinus tarsi syndrome

- Osteochondral defects

- Peroneal tendinopathy

- Subtalar instability

Prognosis

Literature reveals that anatomic repairs faired with the best results, averaging 85-95% good to excellent postoperative results, however patients who had poor tissue quality, long-standing instability, or cavovarus foot type with ligamentous laxity failed to recover as well following repair. Surgical repair was utilizing other than anatomic reconstruction, still showed promising results with about 88% of patients relating good to excellent results. Another article which employed high demand athletes with chronic lateral ankle instability reported a 94% return to previous sports after surgical repair[14].

Complications

Complications of surgery can include; continued pain, infection, failure of procedure (continued instability), nerve injury (3.8-9.7%)[15], wound healing complications (4%), stiffness, impingement from overtightening, amputation, and death.

Chronic lateral ankle instability without surgical intervention may lead to an unbalance ankle and subtalar joint thus resulting in early-onset of degenerative joint disease.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The focus of rehabilitation should be a return to previous activity levels. Range-of-motion exercise and isometric and isotonic strength-training exercises should be included as part of recovery. During the progression of rehabilitation, a succession of proprioceptive training should be incorporated, followed by sports specific activities to prepare the athlete to return to competition [16].

Following surgery, the operative extremity is placed in a well-padded splint with the foot in a neutral or slightly everted position. The patient will remain non-weight bearing until directed otherwise by his surgeon. Sutures remain intact for 2-3 weeks following the procedure, and at that time the surgeon may initiate a gentle range of motion exercises to promote venous circulation. The patient will then be placed in a short leg walking cast or boot and allowed to transition to full protected weight-bearing over the next 2-4 weeks. Next, the patient will be transitioned to an ankle support orthosis and begin formal physical therapy.

The postoperative protocol will likely vary from depending on the surgeon and based on the procedure required and any adjunctive procedures performed in addition to ankle stabilization.

Consultations

- Podiatry

- Orthopedics

- Physical therapy

- Radiology

- Emergency medicine

Deterrence and Patient Education

When there is injury, conservative management is always the preferred method of treatment. For milder injuries, simple rest, ice, compression, and elevation may prove to be the best treatment. For more severe injuries physical therapy may prove to be beneficial, and in cases that prove resistant to physical therapy, surgery may eventually be indicated. Surgical outcomes are generally good, leading to decreased pain and increased function.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lateral ankle instability is a relatively common condition that is mainly treated by podiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, and physical therapists. A close relationship is formed between the patient, the surgeon and the therapist to gauge the progress of therapy and deem if surgery does become necessary. While not every patient will need surgery, it is beneficial for all involved to have an understanding of the treatment plan. If an operation is pursued, rather than other options, healthcare providers will join the team such as perioperative nurses, anesthesia staff, and pharmacists.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hertel J. Functional Anatomy, Pathomechanics, and Pathophysiology of Lateral Ankle Instability. Journal of athletic training. 2002 Dec:37(4):364-375 [PubMed PMID: 12937557]

Balduini FC, Vegso JJ, Torg JS, Torg E. Management and rehabilitation of ligamentous injuries to the ankle. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 1987 Sep-Oct:4(5):364-80 [PubMed PMID: 3313619]

Colville MR. Surgical treatment of the unstable ankle. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1998 Nov-Dec:6(6):368-77 [PubMed PMID: 9826420]

Chan KW, Ding BC, Mroczek KJ. Acute and chronic lateral ankle instability in the athlete. Bulletin of the NYU hospital for joint diseases. 2011:69(1):17-26 [PubMed PMID: 21332435]

Hosea TM, Carey CC, Harrer MF. The gender issue: epidemiology of ankle injuries in athletes who participate in basketball. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2000 Mar:(372):45-9 [PubMed PMID: 10738413]

Smith RW, Reischl SF. Treatment of ankle sprains in young athletes. The American journal of sports medicine. 1986 Nov-Dec:14(6):465-71 [PubMed PMID: 3099587]

Ekstrand J, Tropp H. The incidence of ankle sprains in soccer. Foot & ankle. 1990 Aug:11(1):41-4 [PubMed PMID: 2210532]

Milgrom C, Shlamkovitch N, Finestone A, Eldad A, Laor A, Danon YL, Lavie O, Wosk J, Simkin A. Risk factors for lateral ankle sprain: a prospective study among military recruits. Foot & ankle. 1991 Aug:12(1):26-30 [PubMed PMID: 1959831]

Broström L. [Ankle sprains]. Lakartidningen. 1967 Apr 19:64(16):1629-44 [PubMed PMID: 6046213]

Stephens MM, Sammarco GJ. The stabilizing role of the lateral ligament complex around the ankle and subtalar joints. Foot & ankle. 1992 Mar-Apr:13(3):130-6 [PubMed PMID: 1601340]

Kannus P, Renström P. Treatment for acute tears of the lateral ligaments of the ankle. Operation, cast, or early controlled mobilization. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1991 Feb:73(2):305-12 [PubMed PMID: 1993726]

Lynch SA, Renström PA. Treatment of acute lateral ankle ligament rupture in the athlete. Conservative versus surgical treatment. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 1999 Jan:27(1):61-71 [PubMed PMID: 10028133]

Dreyer MA, Dookie A. A Case of Neglected Achilles Rupture after an Ankle Sprain. Military medicine. 2019 Mar 1:184(3-4):e306-e310. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy203. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30137531]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLi X, Lin TJ, Busconi BD. Treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability: a modified Broström technique using three suture anchors. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2009 Dec 2:4():41. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-4-41. Epub 2009 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 19954540]

Al-Mohrej OA, Al-Kenani NS. Chronic ankle instability: Current perspectives. Avicenna journal of medicine. 2016 Oct-Dec:6(4):103-108 [PubMed PMID: 27843798]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMattacola CG, Dwyer MK. Rehabilitation of the Ankle After Acute Sprain or Chronic Instability. Journal of athletic training. 2002 Dec:37(4):413-429 [PubMed PMID: 12937563]