Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Arm Quadrangular Space

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Arm Quadrangular Space

Introduction

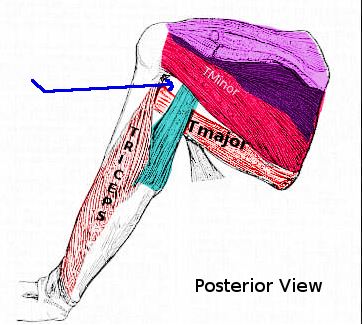

The quadrangular (or quadrilateral) space is so named because of the shape of its anatomic boundaries (see Image. Quadrangular Space, Posterior View). The posterior humeral circumflex artery (PHCA) and axillary nerve exit the axilla and transit this space to their destinations within the posterolateral shoulder. The axillary nerve arises from the posterior brachial plexus cord and divides into musculocutaneous branches, typically before entering or within the quadrangular space.[1] The PHCA bifurcates into anterior and posterior branches inside the region.[2]

The quadrangular space is a significant anatomic landmark for various diagnostic and surgical procedures. Quadrangular space syndrome (QSS) is a condition manifesting with axillary nerve or PHCA compression symptoms arising from various etiologies. Understanding this space's anatomy and functional significance is imperative for treating various upper limb conditions.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Structure

The quadrangular space has 4 anatomic borders. The teres minor comprises the superior border. The teres major forms the inferior edge. The long head of the triceps brachii muscle delineates the medial margin. The surgical humeral neck marks the lateral border. The axillary nerve passes cranial to the PHCA within the quadrangular space.[3]

Function

The quadrangular space provides a passageway for the axillary nerve and the PHCA as these structures exit the axilla and supply the posterolateral shoulder.[4] The axillary nerve is a terminal posterior cord branch, innervating the teres minor, deltoid, glenohumeral articulation, and skin over the inferior deltoid. The PHCA provides 64% of the blood supply to the head of the humerus.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The axillary artery is divided by the pectoralis minor into 3 parts. The 1st part lies medial to the pectoralis minor and has 1 branch, the superior thoracic artery. The 2nd part lies posterior to the pectoralis minor and has 2 branches, the thoracoacromial and lateral thoracic arteries. The thoracoacromial arterial trunk has 4 terminal branches: pectoral, deltoid, acromial and clavicular. The 3rd part lies lateral to the pectoralis minor and has 3 branches: the PHCA and the subscapular and anterior humeral circumflex (AHCA) arteries.[6] The PHCA divides into anterior and posterior branches within the quadrangular space. These branches primarily perfuse the superior, inferior, and lateral portions of the humeral head and surrounding muscles. The PHCA's branches course around the surgical humeral neck to supply most of the proximal humerus.

The AHCA was previously regarded as the primary arterial source of the proximal humerus. However, Hettrich et al's study redefined current concepts by quantitatively assessing this artery's relative contribution to the proximal humeral circulation. Hettrich's group confirmed that approximately 64% of the humeral head's circulation is derived from the PHCA, while the remaining 36% comes from the AHCA.[7] The study is clinically relevant as it helped provide insight regarding the relatively low osteonecrosis rates associated with 3- and 4-part proximal humeral fractures.[8]

Nerves

The axillary nerve, which passes through the quadrangular space, arises from the posterior brachial plexus cord, crosses the subscapularis muscle and tendon anteroinferiorly, and traverses posteriorly through the quadrangular space. The axillary nerve runs superiorly to the PHCA within the quadrangular space and splits into anterior and posterior branches. The anterior axillary branch supplies the anterior deltoid. The posterior axillary branch supplies the posterior deltoid and teres minor. This nerve segment also gives off the superolateral brachial cutaneous nerve, which innervates the skin of the distal 2/3 of the posterior deltoid. Together, the anterior and posterior branches supply the middle 3rd of the deltoid muscle and the shoulder joint capsule.

The posterior division derivatives receive fibers from C5 to T1 and unite to form the posterior cord, which gives rise to the upper and lower subscapular, thoracodorsal, axillary, and radial nerves. Spinal contributions to these nerves are as follows:

- Upper subscapular nerve: C5

- Lower subscapular nerve: C6

- Thoracodorsal nerve: C6 to C8

- Axillary nerve: C5 and C6

- Radial nerve: C5 to T1

These different nerve contributions are significant, especially in the axillary and radial nerves, which follow the proximal-distal myotome rule. This principle states that more rostral spinal nerve roots typically innervate proximal muscle groups, while more caudal roots innervate distal muscles. Thus, the axillary nerve myotomes in the shoulder area are essentially innervated by the more superior C5 and C6 fibers. In contrast, the radial nerve myotomes, including the posterior arm, forearm, and hand, are supplied by the C5, C6, and more inferior roots until T1.[9]

Muscles

Muscles Bordering the Quadrangular Space

Three of the 4 structures delineating the quadrangular space are the teres minor and major and the long head of the triceps brachii. The teres minor originates from the lateral scapular border and inserts on the greater humeral tubercle. This muscle externally rotates the arm at the glenohumeral joint. The teres major originates from the scapula's inferior angle and inserts on the medial lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus. This muscle adducts, medially rotates, and helps extend the arm.[10] The teres major also contributes to glenohumeral joint stability.[11] The long head of the triceps brachii originates from the scapula's infraglenoid tubercle and inserts on the ulna's olecranon process. The triceps long head extends and adducts the arm at the glenohumeral joint and extends the forearm at the elbow joint.[12]

Deltoid Neurovasculature

The deltoid's neurovasculature arises from the structures traversing the quadrangular space. The axillary nerve innervates the deltoid, while the PHCA's branches perfuse the muscle.

The deltoid originates from the clavicle's lateral 3rd and the scapula's acromion and spine, inserting afterward on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus. The deltoid is divided into 3 parts with different origins and functions. Collectively, the deltoid segments primarily abduct the arm, but each part may also be stimulated independently. The anterior (clavicular) part medially rotates, abducts, and flexes the arm. The middle (acromial) portion is the main contributor to arm abduction. The posterior (spinal) segment laterally rotates and extends the arm at the shoulder. The synergy between the clavicular and spinal heads enables the deltoid to contribute to arm adduction.[13]

Physiologic Variants

Anatomical variants of the quadrangular space and its contents are clinically significant, as these anomalies may cause pathology or diagnostic and surgical problems. Variations may involve the muscles bordering this region. For example, McClelland et al observed quadrangular space tightening during external and internal arm rotation due to a fibrous sling connecting the long head of the triceps to the teres major.[14] PHCA tortuosity is implicated as the cause of QSS in Mohandas Rao et al's study.[15] The PHCA may also arise from the subscapular artery instead of the axillary artery's 3rd part, which can change its course near the quadrangular space.

Axillary nerve branching and course variants may also impact the quadrangular space. Beytell et al reported that 52% of the 51 cadavers studied exhibited axillary nerve branching within the space, with the rest displaying branching proximal to the site. This variability may influence surgical planning using the axillary approach. Meanwhile, Pires et al documented the presence of an accessory subscapularis muscle passing anterior to the axillary nerve proximal to the quadrilateral space, which can give rise to QSS.[16]

Surgical Considerations

Quadrangular Space Syndrome

QSS is rare but has a known predilection for athletes and people in certain occupations. The condition is often misdiagnosed, requiring a high index of suspicion in patients aged 20 to 40 years with a history of compression symptoms and engaging in activities requiring repetitive overhead arm motion. Individuals who may be at risk include baseball pitchers, volleyball players, swimmers, electricians, and painters.[17]

QSS symptoms arise from compression of the axillary nerve and PHCA. Fibrous bands, trauma, and hypertrophy of adjacent muscles are some possible causes.[18] Patients often present with shoulder pain and debility.[19] Shoulder pain is commonly located posterolaterally and described as worsening with shoulder abduction and external rotation.[20]

QSS may be rare but is nevertheless an important differential for shoulder pain. The condition may be confused with rotator cuff tears, frozen shoulder syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, cervical radiculopathy, and suprascapular nerve entrapment syndrome. Modalities typically used for diagnosis include electromyography, magnetic resonance imaging, and arteriography. A lidocaine block is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Recently, musculoskeletal ultrasound has been used to diagnose QSS in combination with clinical symptoms.[21]

Nonoperative treatment

Most patients with QSS are treated nonoperatively, which is often sufficient for both acute and chronic cases. Improvement typically occurs within 3 to 6 months. Conservative treatments include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug intake and activity modification. Physical therapy protocols usually include glenohumeral joint mobilization, periscapular and rotator cuff strengthening programs, and posterior capsular stretching. Injecting 3 to 5 cc of 1% lidocaine into the quadrangular space can relieve pain and other symptoms.

Surgical management

Surgery is indicated if QSS does not resolve after 6 months of conservative treatment. The technique depends on the etiology. In patients with vascular QSS (see Clinical Significance), surgical management depends on the extent of PHCA damage. PHCA aneurysm requires resection. An arterial thrombus may be treated with PHCA ligation, with or without thrombolysis. Thromboembolectomy is indicated in PHCA thrombus formation with digital emboli.[22]

Open decompression may benefit patients with fibrous adhesions or scarring impinging the axillary nerve. Earlier surgical decompression should be considered in the presence of a space-occupying lesion or significant weakness and functional disability. Paralabral cysts, often associated with shoulder labral pathology, may require cyst decompression and labral repair.

Axillary nerve and PHCA identification and palpation during surgery help avoid iatrogenic risk to these key structures. Additionally, following quadrangular space decompression, the surgeon should palpate the axillary nerve and PHCA while an assistant gently abducts and externally rotates the patient’s shoulder. These measures ensure that these neurovascular structures can move unrestricted and that the PHCA maintains a steady pulse throughout the motion.[23]

Other Surgical Considerations

Surgical management of glenohumeral and proximal humeral pathology may be approached anteriorly or posteriorly. Pizzo et al used the anterior (deltopectoral) approach to perform reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. This technique is often anatomically challenging. However, the anterior approach allowed them to avert neurologic injury in a patient with the axillary nerve anomalously passing beneath the cephalic vein inside the deltopectoral triangle.[24] Meanwhile, anatomists recommend the posterior approach, allowing easier quadrangular space dissection. However, this surgical technique is associated with a heightened risk of damaging the deltoid and its innervation, possibly causing chronic pain.

The interscalene block is commonly employed during shoulder surgery. However, the technique often causes ipsilateral phrenic nerve paralysis. A recent study suggests that combining axillary and suprascapular nerve blocks for shoulder surgery anesthesia may be an effective alternative to the interscalene approach to preserve phrenic nerve function. Axillary nerve block using this technique entails injecting the anesthetic within the quadrangular space.[25]

The thoracodorsal nerve and the nerve to the medial head of the triceps brachii can be implanted in the axillary nerve to restore its function. Access to the axillary nerve is obtained by opening up the quadrilateral space with the patient in the lateral decubitus position.[26]

Clinical Significance

The neurovascular structures within the quadrangular space are essential for upper extremity function. Misdiagnosis of quadrangular space injuries can occur due to their complex presentation.

Neurovascular Compression Within the Quadrangular Space

QSS occurs when the neurovascular structures within the quadrangular space are mechanically compressed. Three types of QSS have been identified.

Neurogenic QSS (nQSS) occurs when the axillary nerve is compressed within the quadrangular space. Patients with nQSS may exhibit quadrangular space tenderness, nondermatomal radicular pain, paresthesia often concentrated on the posterior and lateral arm, deltoid muscle fasciculations during abduction, and potential muscle atrophy and weakness due to denervation. Vascular QSS (vQSS) occurs when the PHCA is compressed within the quadrangular space. PHCA ischemia can occur, causing pain, pallor, and diminished or absent distal pulses. Compression may produce PHCA aneurysms and thrombi, as well as digital emboli, causing cyanosis and cold hands and digits. Patients may present with both nQSS and vQSS due to the proximity of the PHCA to the axillary nerve in the quadrangular space.

As mentioned, fibrous band formation within the quadrangular space is the most common cause of QSS. Muscular hypertrophy can also result in QSS. Glenohumeral joint abduction and external rotation are common in sports requiring overhead arm movements, such as baseball, volleyball, and swimming. These actions are also frequently involved when performing activities such as cleaning windows and installing ceiling lights. Teres major hypertrophy and space-occupying lesions such as paralabral cysts (often inferior labral tears), lipomas, axillary schwannomas, humeral osteochondromas, and fracture fragments can also cause QSS.[27]

QSS is often diagnostically challenging. Imaging methods such as radiography and magnetic resonance are generally useful when investigating the cause of treatment-refractory shoulder pain.[28]

Arm Trauma

Humeral fractures, particularly those involving the proximal humeral shaft, may traumatically damage the neurovascular structures within or near the quadrangular space, potentially resulting in complications like avascular necrosis of the humeral head. Clinicians should thus assess neurovascular function in patients with this injury.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Beytell L, Mennen E, van Schoor AN, Keough N. The surgical anatomy of the axillary approach for nerve transfer procedures targeting the axillary nerve. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2023 Jul:45(7):865-873. doi: 10.1007/s00276-023-03168-x. Epub 2023 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 37212871]

Tang A, Varacallo MA. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Posterior Humeral Circumflex Artery. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855867]

Rothe C, Lund J, Jenstrup MT, Steen-Hansen C, Lundstrøm LH, Andreasen AM, Lange KHW. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of selective axillary nerve block after arthroscopic subacromial decompression. BMC anesthesiology. 2020 Jan 31:20(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12871-020-0952-y. Epub 2020 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 32005160]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFlynn LS, Wright TW, King JJ. Quadrilateral space syndrome: a review. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2018 May:27(5):950-956. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.10.024. Epub 2017 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 29274905]

Mostafa E, Imonugo O, Varacallo MA. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Humerus. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521242]

Talbot NC, D'Antoni JV, Soileau LG, Storey NR, Fakoya A. Unusual Origin of the Posterior Circumflex Humeral Artery: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023 Mar:15(3):e36316. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36316. Epub 2023 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 37077595]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHettrich CM, Boraiah S, Dyke JP, Neviaser A, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Quantitative assessment of the vascularity of the proximal part of the humerus. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2010 Apr:92(4):943-8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01144. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20360519]

Khmelnitskaya E, Lamont LE, Taylor SA, Lorich DG, Dines DM, Dines JS. Evaluation and management of proximal humerus fractures. Advances in orthopedics. 2012:2012():861598. doi: 10.1155/2012/861598. Epub 2012 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 23316376]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOkwumabua E, Black AC, Thompson JH. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Nerves. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252312]

Juneja P, Hubbard JB. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Arm Teres Minor Muscle. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020696]

Barra-López ME, López-de-Celis C, Pérez-Bellmunt A, Puyalto-de-Pablo P, Sánchez-Fernández JJ, Lucha-López MO. The supporting role of the teres major muscle, an additional component in glenohumeral stability? An anatomical and radiological study. Medical hypotheses. 2020 Aug:141():109728. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109728. Epub 2020 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 32298921]

Tiwana MS, Sinkler MA, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Triceps Muscle. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725681]

Larionov A, Yotovski P, Link K, Filgueira L. Innervation of the clavicular part of the deltoid muscle by the lateral pectoral nerve. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2020 Nov:33(8):1152-1158. doi: 10.1002/ca.23555. Epub 2020 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 31894613]

McClelland D, Paxinos A. The anatomy of the quadrilateral space with reference to quadrilateral space syndrome. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2008 Jan-Feb:17(1):162-4 [PubMed PMID: 17993281]

Mohandas Rao KG, Somayaji SN, Ashwini LS, Ravindra S, Abhinitha P, Rao A, Sapna M, Jyothsna P. Variant course of posterior circumflex humeral artery associated with the abnormal origin of radial collateral artery: could it mimic the quadrangular space syndrome? Acta medica Iranica. 2012:50(8):572-6 [PubMed PMID: 23109033]

Pires LAS, Souza CFC, Teixeira AR, Leite TFO, Babinski MA, Chagas CAA. Accessory subscapularis muscle - A forgotten variation? Morphologie : bulletin de l'Association des anatomistes. 2017 Jun:101(333):101-104. doi: 10.1016/j.morpho.2017.04.003. Epub 2017 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 28522228]

Davis DD, Nickerson M, Varacallo MA. Swimmer's Shoulder. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262079]

Charmode S, Mehra S, Kushwaha S. Revisiting the Surgical Approaches to Decompression in Quadrilateral Space Syndrome: A Cadaveric Study. Cureus. 2022 Feb:14(2):e22619. doi: 10.7759/cureus.22619. Epub 2022 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 35371758]

Kemp TD, Kaye TR, Scali F. Quadrangular Space Syndrome: A Narrative Overview. Journal of chiropractic medicine. 2021 Mar:20(1):16-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2021.01.002. Epub 2021 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 34025301]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen H, Narvaez VR. Ultrasound-guided quadrilateral space block for the diagnosis of quadrilateral syndrome. Case reports in orthopedics. 2015:2015():378627. doi: 10.1155/2015/378627. Epub 2015 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 25685573]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhang J, Zhang T, Wang R, Wang T. Musculoskeletal ultrasound diagnosis of quadrilateral space syndrome: A case report. Medicine. 2021 Mar 12:100(10):e24976. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024976. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33725866]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrown SA, Doolittle DA, Bohanon CJ, Jayaraj A, Naidu SG, Huettl EA, Renfree KJ, Oderich GS, Bjarnason H, Gloviczki P, Wysokinski WE, McPhail IR. Quadrilateral space syndrome: the Mayo Clinic experience with a new classification system and case series. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2015 Mar:90(3):382-94. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.012. Epub 2015 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 25649966]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHangge PT, Breen I, Albadawi H, Knuttinen MG, Naidu SG, Oklu R. Quadrilateral Space Syndrome: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 Apr 21:7(4):. doi: 10.3390/jcm7040086. Epub 2018 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 29690525]

Pizzo RA, Lynch J, Adams DM, Yoon RS, Liporace FA. Unusual anatomic variant of the axillary nerve challenging the deltopectoral approach to the shoulder: a case report. Patient safety in surgery. 2019:13():9. doi: 10.1186/s13037-019-0189-1. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 30815032]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSaravanan R, Nivedita K, Karthik K. Selective Suprascapular and Axillary nerve (SSAX) block - A diaphragm sparing regional anesthetic technique for shoulder surgeries: A case series. Saudi journal of anaesthesia. 2022 Oct-Dec:16(4):457-459. doi: 10.4103/sja.sja_782_21. Epub 2022 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 36337404]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJanes LE, Crowe C, Shah N, Sasson D, Ko JH. Alternative Nerve Transfer for Shoulder Function: Thoracodorsal and Medial Triceps to Anterior Axillary Nerve. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2022 Oct:10(10):e4614. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004614. Epub 2022 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 36299819]

Rollo J, Rigberg D, Gelabert H. Vascular Quadrilateral Space Syndrome in 3 Overhead Throwing Athletes: An Underdiagnosed Cause of Digital Ischemia. Annals of vascular surgery. 2017 Jul:42():63.e1-63.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.10.051. Epub 2017 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 28284923]

Bredella MA, Tirman PF, Fritz RC, Wischer TK, Stork A, Genant HK. Denervation syndromes of the shoulder girdle: MR imaging with electrophysiologic correlation. Skeletal radiology. 1999 Oct:28(10):567-72 [PubMed PMID: 10550533]