Credentialing and Privileging Provider Profiling

Credentialing and Privileging Provider Profiling

Definition/Introduction

Provider profiling involves systematically compiling and analyzing information related to the healthcare provider to define their characteristics in certain areas, including knowledge, professionalism, communication, procedural competency, and patient outcomes.[1] Profiles are continually expanded and analyzed as a provider progresses beyond initial certification to ongoing practice throughout medical staff membership. Institutional medical staff committees reference the provider's existing profile when deciding on credentialing, privileging, advancement, promotion, acceptance to advanced training, and employment.[2] Credentialing assesses if a provider meets institutional requirements for staff inclusion, such as training, board certification, and malpractice event history. In contrast, privileging evaluates a provider's behavior, skills, and procedures within their practice scope at the institution. In the initial credentialing and privileging phase, provider profiling entails collecting and analyzing comprehensive multifactorial data points used to assess the provider's potential clinical competence, professionalism, and adherence to the core competencies expected of a future medical staff member.

Provider profiling continues throughout medical staff membership to demonstrate ongoing quality performance and ensure the provider's medical and procedural quality and currency. These ongoing profiles are termed Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation (OPPE) and are a form of evidence-based credentialing.[3] In the United States, OPPE is required by the Joint Commission to occur more than once annually and at reappointment every 2 to 3 years.[3][4] Focused Professional Practice Evaluation (FPPE) is a review process also required by the Joint Commission under 3 circumstances: at a provider's initial appointment with the medical staff, when an existing provider requests a new privilege, or when an OPPE report or incident raises concern for a current providers' competence.[5][6][3]

Both the OPPE and the FPPE processes must be uniform, data-driven, consistent, free from bias, and fairly applied to every provider of every specialty, including physicians, advanced practice providers such as physician assistants and advanced practice registered nurses, midwives, dentists, chiropractors, podiatrists, psychologists, and others.[7][8] Although the Joint Commission does not give specific direction for OPPE and FPPE structure and organization, they require clearly defined peer review processes for each specialty and provider type.[4] This includes delineating the qualitative and quantitative metrics, methods of data collection, location of secure storage, period of evaluation, circumstances requiring external review, and the process for data review.[9][3] Depending on the hospital or organizational structure, the committees overseeing FPPE and OPPE processes may include the Medical Executive Committee (MEC), Credentials Committee, Quality Improvement Committee, Peer Review Committee, and Departmental or Specialty Committees. Although details from OPPE and FPPE are not reported to the Joint Commission and are generally protected from discovery, the Joint Commission can, in special circumstances, request access from these institutional committees.[10] Ultimately, provider profiling should deliver feedback to improve professional competence and for overall patient safety and quality of care rather than being punitive to individual providers.[11][12]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Profiling in Initial Provider Credentialing

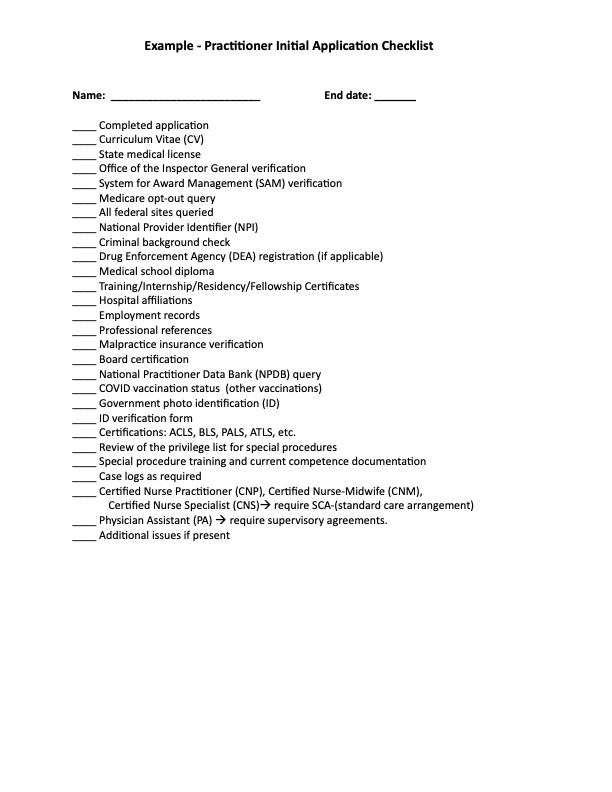

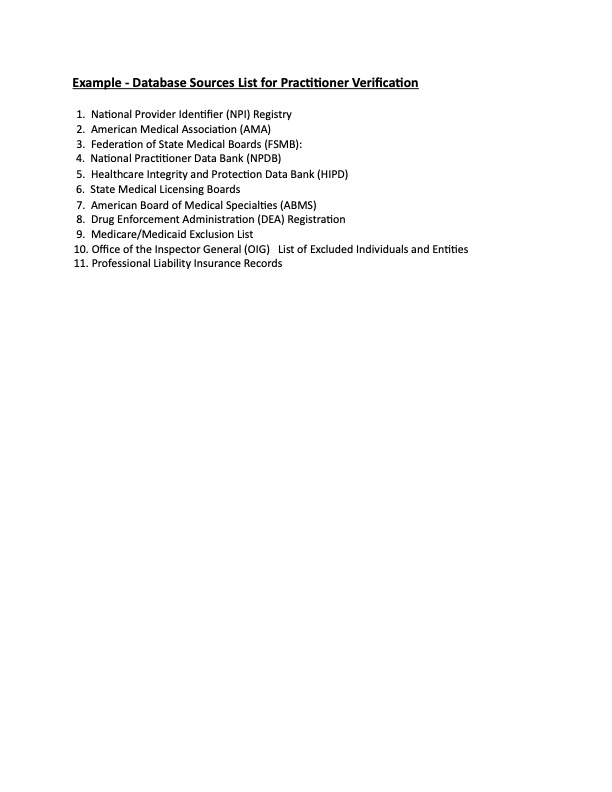

Provider profiling is critical to initial credentialing for new candidates applying to a healthcare facility. The facility transfers data for the profile from the applicant directly and from data banks, training programs, schools, peers, previous practice sites, and background. The information must be verified as a primary source (PSV) by the issuing body as much as possible. PSV applies particularly to certifications, licenses, diplomas, and peer references. An initial application checklist typically consists of 20 to 30 items in length and commonly takes 60 to 90 days to complete and to be verified by the institution (see Image. Initial Application Checklist). Verification involves querying multiple databases, including the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), and others (see Image. Verification Databases). Upon file completion by the Medical Staff Office (MSO), the application is reviewed by the Credentials Committee and, if accepted, is forwarded to the MEC and then to the facility's Board of Directors (BOD) for final approval.

Profiling for the Focused Professional Practice Evaluation (FPPE)

FPPE is a standard process mandated by the Joint Commission and used by medical facilities and the medical staff when a practitioner needs a focused plan to assess and ensure the practitioner delivers high-quality patient care. There are 2 types of FPPE. One is a proactive FPPE assigned to all providers new to the institution who are undergoing initial credentialing and privileging. The second type of FPPE is a reactive FPPE that occurs in response to a red flag or triggering event in an already established provider.

The institution must establish 4 vital elements as mandated by the Joint Commission: the evaluation criteria, privilege-specific monitoring methods, duration of monitoring, and reasons to refer for external monitoring.[13] This proactive FPPE process is required for all new medical staff appointments. It is routinely implemented as a part of the final phase of credentialing and privileging and must be completed within 6 months of hiring.[6][7][9] The procedure for new physicians involves incorporating essential facility-based data into the provider's profile to authenticate proficiency in specific competency areas.

Proactive FPPEs should be clearly defined and consistent for new privileges but can be specific to the institution, specialty, and the distinct privilege requested.[3][7] Still, suppose the incoming new staff member has a history of red flags or concerns in 1 or more core competencies based on their incoming profile. In that case, the FPPE will also be customized to address those specific concerns. The FPPE process can include any data-gathering modality from retrospective chart review to direct observation and proctoring. Action plans for areas of improvement are developed based on FPPE reports and can consist of suggested interventions over a specified period for both clinical and citizenship issues.[10] A remediation plan is required in cases of recurring errors or if the errors do not pass the substitution test, indicating that another provider with equivalent training would not have committed similar errors.[14]

- Actions for clinical concerns may include focused chart reviews, direct observation or mentoring with a senior or expert provider, participation in quality improvement activities, focused continuing education or simulation training, and monitoring of performance data for procedures, interventions, and admissions.[14][8]

- Actions for citizenship issues may include referral for counseling for behavioral or potential substance use, anger management, professionalism training, or leadership development.[8][14]

Potential outcomes after FPPE include closure without further action, referral for external review (especially novel procedures), continued direct observation or supervision, a letter of reprimand, and rarely suspension or termination of privileges.[15] Standardization of the peer review process is essential to prevent abuse or litigation.[16] This often requires training, structured assessments, and inter-rater agreement.[16] Institutional use of performance data must be valid and fair to avoid inappropriate or detrimental consequences to providers.[17] The peer review process is protected from retaliatory litigation from providers who have lost privileges by the 1986 federal Healthcare Quality Improvement Act, which requires good faith, confidentiality, and opportunity for a fair hearing before final adverse action.[15]

Reactive-type FPPEs can be implemented for current medical staff providers to address concerns reported to the Multidisciplinary Peer Review Committee (MPRC) or the Provider Advocacy/Professionalism Committee (PAC). Typically, in this circumstance, the appropriate committee manages FPPE implementation and tracking as a collegial intervention with oversight. Escalation to the MEC occurs when the issue demands a formal process or action. This escalation occurs most commonly for patterns of noncompliance or isolated severe events. Triggers for reactive FPPEs for current medical staff providers can include a variety of clinical, citizenship, or health concerns.

- Clinical triggers for an FPPE might include incidents identified through peer review or complaints from staff, patients, or families. Additionally, the occurrence of sentinel events necessitates a review within 3 days and completion of a systemic improvement plan within 30 days.[8] Other triggers may include a high complication rate, recurring near misses, or a pattern of adverse events. Instances of malpractice suggesting deviations from the standard of care, particularly those involving purposeful behavior, reckless disregard, or gross negligence, could also prompt an FPPE. Furthermore, a low volume of procedures, especially when no data is available, and falling below established threshold values for OPPE clinical performance indicators, often by 2 standard deviations, are noteworthy considerations.[3][18]

- Citizenship triggers for an FPPE may encompass breaches of the medical staff code of professionalism, including unethical or illegal behavior, poor judgment, and concerns regarding inappropriate or disruptive conduct.[14] Factors such as low performance on board examinations or failure to maintain certification can also prompt an FPPE.[14] Inclusion in the Healthcare Integrity and Protection Data Bank (HIPDB), which identifies providers sanctioned for insurance billing fraud and abuse in healthcare delivery, is another significant trigger. Similarly, being listed in the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), now consolidated with the HIPDB into "The Data Bank," is indicative of issues such as medical malpractice payouts, loss or restriction of professional society membership, certification, licensure, and privileges, exclusion from federal or state healthcare programs, sanction by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), or healthcare-related criminal convictions or civil judgments.[10]

- Health concern triggers for an FPPE might include age, physical, cognitive, or mental health issues or disabilities, and requires a fitness-to-work evaluation per the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Profiling for the Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation (OPPE)

Healthcare institutions and the medical staff use Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation (OPPE) to monitor providers' continuing performance and competency as required by the Joint Commission.

Profiling of provider performance metrics is critical to the OPPE process and focuses mainly on outcome variances. The OPPE process is intended to help ensure the quality of care with continuous tracking, feedback, and action plans directed to areas where opportunities for improvement are identified. Reporting and evaluation intervals for OPPE reports should be more than once every 12 months, with cycle length determined by the institution.[8][9] The OPPE data for each practitioner should be specific to their specialty, relevant, and valid. It should encompass critical metrics to facilitate ongoing quality improvement for the individual practitioner and the broader department and institution.[13][19][20][7][10] Appropriate specialty-specific OPPE metrics may parallel the core competencies of patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).[20][7] OPPE metrics often include data regarding continuing education, patient outcomes, clinical performance quality, documentation, citizenship, and academic issues. Measurements of OPPE data can also include periodic chart reviews or audits, direct observation, proctoring, 360° evaluations, simulation, and external peer review.[3]

- Continuing education profile metrics may include participation in quality assurance committee work, simulation-based learning assessments, web-based testing, maintenance of certification, fellowship training, and continuing medical education (CME).[21][19][20][7]

- Patient outcome metrics may include patient experience evaluated through satisfaction scores, compliments, willingness to return, and complaints.[17] Factors such as length of stay, return visits, readmissions, repeat surgeries, and postprocedure complications like infection, morbidity, and mortality are considered.[4] Diagnostic errors, unnecessary testing and procedures, medicolegal concerns, and compliance with the Universal Protocol for Preventing Wrong Site, Wrong Procedure, and Wrong Person Surgery are vital indicators.[13][20]

- Some peer review committees utilize an algorithm developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (AHRQ), which considers the number of identified quality issues and harm categories, including no error, no harm; error, no harm; error with harm; and error with patient death.[16]

- Clinical performance quality metrics encompass factors such as productivity, measured through case or procedural volume and relative value units, internal cost per episode of care, procedural numbers, testing utilization metrics, peer evaluation surveys from multiple sources, and performance benchmarking through entities like CMS, Vizient, or the Emergency Department Benchmarking Association.[20][17][13]

- Additionally, over 15 specialty registries reflect national consensus standards, including DataDerm™ for dermatologists, the National Anesthesia Clinical Outcome Registry (NACOR) for anesthesiologists, ACR National Radiology Data Registry for radiologists, the Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) for rheumatologists, Clinical Emergency Data Registry (CEDR) for emergency physicians, the PRIME Registry for family practitioners, and others.[22]

- Documentation metrics include documentation accuracy, such as unsupported diagnoses, insufficient medical decision-making, inaction on critical results, addressing discrepancies between provider and nursing notes, and avoiding inappropriate macros and confusing abbreviations.[19] Additionally, it involves the supervision of trainees and advanced practice providers (APPs), adherence to clinical guidelines, such as the Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG), and compliance with CMS quality measures, including the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS).[23]

- Citizenship metrics may include behavior issues, interpersonal skills, adherence to policies and procedures, timeliness of medical records, responses to calls and consults, attendance at required meetings, billing irregularities, and occasionally ethical issues.

- Academic metrics may include publications, invited lectures, regional/national presentations, scholarships, grants, academic rank, conference attendance, and trainee feedback.

Metrics for specialty-specific OPPE profile reports should be distributed to the individual practitioner and the Department Chair (or Section Chief) to review and identify opportunities for improvement (OFI). OFIs may involve a particular provider or a group of providers. Addressing deviations in the quality of care may involve a simple action, an FPPE process, or an entire group change in process or procedures.[24]

Profiling for Adverse Events or Professionalism Issues

Incident reports related to performance or professionalism need to be assessed within the framework of the provider's existing OPPE profile report. A significant procedure complication known to occur at an established rate may be unavoidable. However, suppose a practitioner has an ongoing complication rate significantly above their peers or above a national standard. In that case, an FPPE followed by a corrective plan may be indicated. Typically, this would be an action following a Multidisciplinary Peer Review Committee (MPRC) review and recommendation.

Similarly, a practitioner who receives a complaint regarding a professionalism or conduct concern will be referred to a medical staff Practitioner Advocacy/Professionalism Committee (PAC) for review. If the occurrence is severe or demonstrates a pattern of behavior, an FPPE followed by an action plan for correction or an escalation to the MEC may be implemented. Corrective plans for professionalism often involve the escalation of intervention methods stepwise based on the severity of the incident in the context of the profile of previous events.

Profiling at Reappointment to the Medical Staff

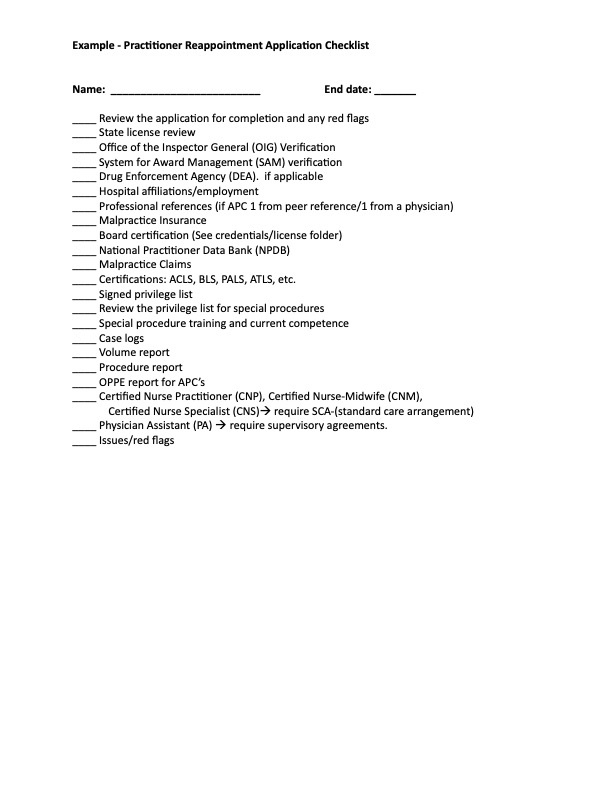

All practitioners must undergo reappointment to the medical staff on a schedule of at least every 3 years. The reappointment process involves a comprehensive assessment of the practitioner's current performance profile with the institution and the medical staff. The OPPE report, in conjunction with a current query of the same databases accessed in initial credentialing (see Image. Reappointment Checklist), establishes the foundation element for review by the Credentials Committee and the Chair of the Department. The reappointment profiling report determines whether the provider will receive an unconditional membership reappointment to the medical staff versus a conditional reappointment or is not recommended for reappointment. Individual privileges are also evaluated similarly to decide on the continuation or revocation of each privilege. The recommendation by the Credentials Committee is forwarded to the MEC and then to the facility's Board of Directors for final approval.

Clinical Significance

Provider and healthcare worker profiling is a critically important part of the credentialing and privileging process. Credentialing and privileging are performed thoroughly and completely to ensure a competent medical staff capable of delivering the required high-quality care. While there is limited evidence linking quality measures to peer performance, and no studies have yet evaluated the impact of peer evaluation on patient outcomes, the consistent utilization of profiling through the OPPE process is believed to have a positive influence on continuing education, procedural currency, professionalism, patient safety, and judicious resource utilization. This, in turn, is expected to contribute to enhanced healthcare outcomes.[12][25]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Providing the highest quality patient care begins and ends with the interprofessional healthcare team. Every member is responsible for critical components in ensuring the safe navigation of the patient through the healthcare system with the highest probability of the best outcome. The details of each member of the team's background, training, knowledge, clinical skills, procedural skills, and communication skills set the actual foundation for performance. While each member's knowledge and skills may differ, the overall care delivered hinges on the interprofessional understanding of the other members' roles on the team and the need for high-level communication. Referral for peer review can be made confidentially by any institutional employee.[15]

Institutional staff services are essential to the peer review process, including data analysts for data analysis, monitoring, and reporting; and staff office professionals and administrative assistants for meeting management, administrative tasks, documentation, supervision of root-cause-analyses, and process oversight according to staff bylaws.

Physicians, physician assistants/associates (PAs), advanced practice nurses (APNs), pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals perform effectively to provide patient-centered team-based care, but only if their presence on the team is established through comprehensive profiling at their initial privileging and with ongoing revalidation throughout their careers. OPPE exists for all these professionals, as it must be in any high-reliability, high-risk, team-based, constantly-evolving profession.[9]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Verification Databases. The image is an example list of databases commonly used to verify practitioner information during the provider profiling process.

Contributed by R King, MD.

Modified deidentified document from the Med Staff office of Mercy St. Vincent Medical Center, Toledo, Ohio. Used with permission.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tucker JL 3rd. The theory and methodology of provider profiling. International journal of health care quality assurance incorporating Leadership in health services. 2000:13(6-7):316-21 [PubMed PMID: 11484650]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatel R, Sharma S. Credentialing. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137789]

Hunt JL. Assessing physician competency: an update on the joint commission requirement for ongoing and focused professional practice evaluation. Advances in anatomic pathology. 2012 Nov:19(6):388-400. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318273f97e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23060064]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSteele JR, Hovsepian DM, Schomer DF. The joint commission practice performance evaluation: a primer for radiologists. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2010 Jun:7(6):425-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2010.01.027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20522395]

Loftus ML. OPPE, FPPE, QPS, and why the alphabet soup of physician assessment is essential for safer patient care. Clinical imaging. 2018 Jan-Feb:47():v-vii. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.11.003. Epub 2017 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 29246462]

Makary MA, Wick E, Freischlag JA. PPE, OPPE, and FPPE: complying with the new alphabet soup of credentialing. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2011 Jun:146(6):642-4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.136. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21690440]

Sterling M, Gregg S, Bakshi V, Moll V. A Guide to Performance Evaluation for the Intensivist: Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation and Focused Professional Practice Evaluation in the ICU. Critical care medicine. 2020 Oct:48(10):1521-1527. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004441. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32750247]

Harolds JA. Quality and Safety in Health Care, Part LXXI: Peer Review, Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation, and Focused Professional Practice Evaluation. Clinical nuclear medicine. 2021 Sep 1:46(9):738-740. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003057. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32453075]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHolley SL, Ketel C. Ongoing professional practice evaluation and focused professional practice evaluation: an overview for advanced practice clinicians. Journal of midwifery & women's health. 2014 Jul-Aug:59(4):452-9. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12190. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25066744]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBlankenship JC, Rosenfield K, Jennings HS 3rd. Privileging and credentialing for interventional cardiology procedures. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2015 Oct:86(4):655-63. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25793. Epub 2015 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 25534235]

Donnelly LF, Podberesky DJ, Towbin AJ, Loh L, Basta KH, Platchek TS, Vossmeyer MT, Shook JE. The Joint Commission's Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation Process: Costly, Ineffective, and Potentially Harmful to Safety Culture. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2024 Jan:21(1):61-69. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2023.08.031. Epub 2023 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 37683817]

Donnelly LF, Dorfman SR, Jones J, Bisset GS 3rd. Transition From Peer Review to Peer Learning: Experience in a Radiology Department. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2018 Aug:15(8):1143-1149. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.08.023. Epub 2017 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 29055610]

Walker LE, Phelan MP, Bitner M, Legome E, Tomaszewski CA, Strauss RW Jr, Nestler DM. Ongoing and Focused Provider Performance Evaluations in Emergency Medicine: Current Practices and Modified Delphi to Guide Future Practice. American journal of medical quality : the official journal of the American College of Medical Quality. 2020 Jul/Aug:35(4):306-314. doi: 10.1177/1062860619874113. Epub 2019 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 31516026]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKruskal J, Eisenberg R. Focused Professional Performance Evaluation of a Radiologist--a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Joint Commission Requirement. Current problems in diagnostic radiology. 2016 Mar-Apr:45(2):87-93. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2015.08.006. Epub 2015 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 26365574]

Lepard JR, Yaeger K, Mazzola C, Stacy J, Shuer L, Kimmel K, Counsel of State Neurosurgical Societies. Mechanisms of Peer Review and Their Potential Impact on Neurosurgeons: A Pilot Survey. World neurosurgery. 2022 Nov:167():e469-e474. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.08.032. Epub 2022 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 35973519]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDeyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, Schilling KA, Palmer KB. A Systematic Approach to Clinical Peer Review in a Critical Access Hospital. Quality management in health care. 2016 Oct/Dec:25(4):213-218 [PubMed PMID: 27749718]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeep Hunderfund AN, Park YS, Hafferty FW, Nowicki KM, Altchuler SI, Reed DA. A Multifaceted Organizational Physician Assessment Program: Validity Evidence and Implications for the Use of Performance Data. Mayo Clinic proceedings. Innovations, quality & outcomes. 2017 Sep:1(2):130-140. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.05.005. Epub 2017 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 30225409]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceClevenger MA, Roberts SM, Lattin DL, Harbison RD, James RC. The pharmacokinetics of 2,2',5,5'-tetrachlorobiphenyl and 3,3',4,4'-tetrachlorobiphenyl and its relationship to toxicity. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 1989 Sep 1:100(2):315-27 [PubMed PMID: 2506674]

Smalley CM, Baskin BE, Simon EL, Meldon SW, Muir MR, Borden BL, Trentanelli K, Fertel BS. Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation for Emergency Medicine Physicians in a Large Health Care System. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety. 2021 May:47(5):318-326. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2020.11.002. Epub 2020 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 33358572]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKruskal JB, Eisenberg RL, Ahmed M, Siewert B. Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation of Radiologists: Strategies and Tools for Simplifying a Complex Process. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2018 Oct:38(6):1593-1608. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018180163. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30303807]

Pannekoeke L, Knudsen SAS, Kambe M, Vae KJU, Dahl H. Ongoing training and peer feedback in simulation-based learning for local faculty development: A participation action research study. Nurse education today. 2023 May:124():105768. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2023.105768. Epub 2023 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 36881948]

Morrissette S, Etkin CD, Brodell RT, Pearlman RL. The Use of Clinical Data Registries to Improve Care and Meet Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation Requirements. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety. 2022 Oct:48(10):549-551. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2022.06.003. Epub 2022 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 35843862]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBaker WE. Evaluation of physician competency and clinical performance in emergency medicine. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2009 Nov:27(4):615-26, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2009.07.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19932396]

Stossel TP, Chaponnier C, Ezzell RM, Hartwig JH, Janmey PA, Kwiatkowski DJ, Lind SE, Smith DB, Southwick FS, Yin HL. Nonmuscle actin-binding proteins. Annual review of cell biology. 1985:1():353-402 [PubMed PMID: 3030380]

Thai T, Louden DKN, Adamson R, Dominitz JA, Doll JA. Peer evaluation and feedback for invasive medical procedures: a systematic review. BMC medical education. 2022 Jul 29:22(1):581. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03652-9. Epub 2022 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 35906652]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence