Introduction

The retroperitoneum is an anatomical space located behind the abdominal or peritoneal cavity. Abdominal organs that are not suspended by the mesentery and lie between the abdominal wall and parietal peritoneum are said to lie within the retroperitoneum. Several individual spaces make up the retroperitoneum. These spaces are the anterior pararenal space, posterior pararenal space, and the perirenal space. Each of these spaces contains parts of various organs and structures. These structures include organs that contribute to several systems in the body, including the urinary, adrenal, circulatory, gastrointestinal, and endocrine systems.[1] This article will discuss the structure, function, embryology, and anatomy of the retroperitoneum, and will also include discussion of its clinical significance and specific surgical considerations.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

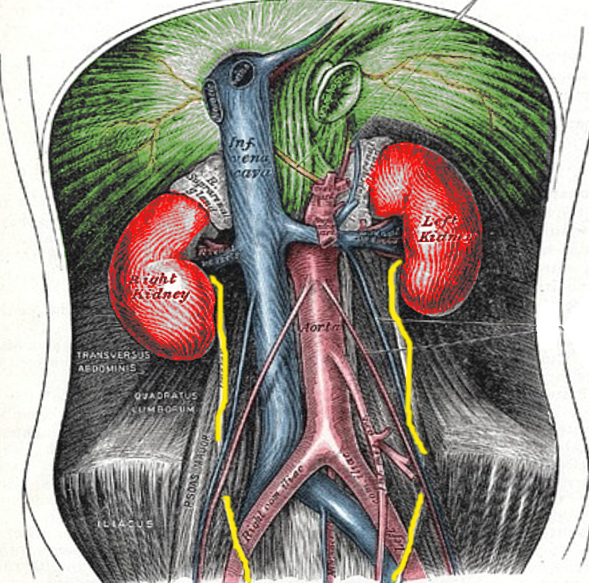

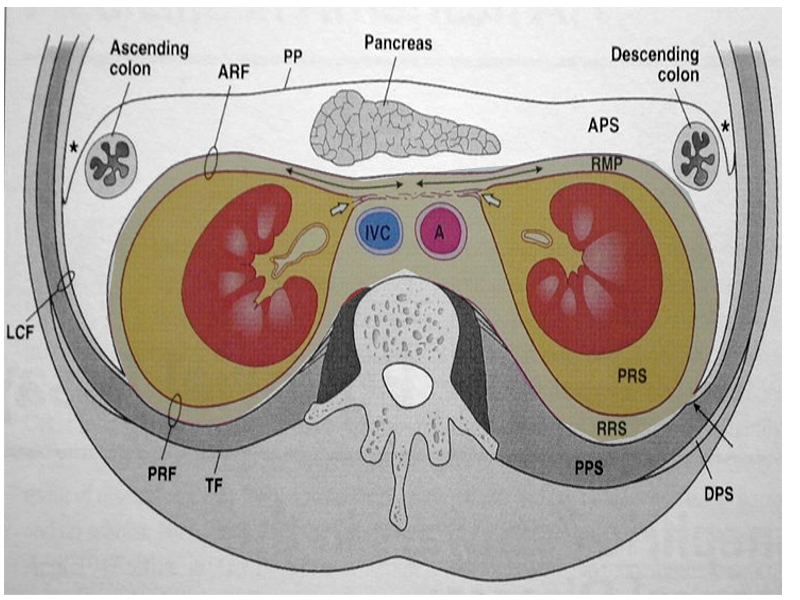

The retroperitoneum divides into three main anatomical spaces: the anterior pararenal space, perirenal space, and posterior pararenal space. The anterior pararenal space contains the head, neck, and body of the pancreas (the tail of the pancreas is within the splenorenal ligament), ascending and descending colon, and the duodenum (except for the proximal first segment). Structures contained within the perirenal space include the adrenal gland, kidney, ureters, and renal vessels. The posterior pararenal space, which is surrounded by the posterior leaf of the renal fascia and muscles of the posterior abdominal wall, contains no major organs and is composed primarily of fat, blood vessels, and lymphatics.[2] There is also a fourth, less well-defined space known as the great vessel space. It lies anterior to the vertebral bodies and psoas muscles and contains the aorta, inferior vena cava, and surrounding fat.[3]

Embryology

The embryologic development of structures located within the retroperitoneum is categorized based on the location they originated from within the abdomen. Retroperitoneal structures can be primarily or secondarily retroperitoneal. Primarily retroperitoneal structures are those that were retroperitoneal during the entirety of development. These structures include the adrenal glands, kidneys, ureters, abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava, and anal canal. Structures considered to be secondarily retroperitoneal were initially suspended in the mesentery, and then later migrated behind the peritoneum during development. These structures include the duodenum (except for the first segment), ascending and descending portions of the colon, and the pancreas (except for the tail).[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The retroperitoneum contains the large vessels of the abdomen and pelvis. Arterial blood supply is from the abdominal aorta and all of its branches. The inferior vena cava and its tributaries provide for venous drainage of the retroperitoneum and its structures.[5] The lymphatic chain of the retroperitoneum is rich and extensive. The lymphatics generally follow arteries, with named lymph nodes typically found near the root of the arteries. Lymph nodes lying in the retroperitoneal space of the abdomen are the inferior diaphragmatic nodes, and the lumbar nodes. Lumbar nodes surround the inferior vena cava and aorta and further classify as left lumbar, intermediate, and right lumbar. Surrounding the great vessels lie, three groups of lymph nodes, with their names corresponding to each vessel. Around the aorta are the pre-aortic, para-aortic, and retro-aortic nodes. Similarly, around the inferior vena cava exist the pre-caval, para-caval, and retro-caval nodes. The retroperitoneal lymphatic chain of the pelvis is made up of the common iliac, external and internal iliac, obturator, and sacral lymph nodes.[6]

Nerves

There is an extensive network of nerves that both pass through and supply the retroperitoneum and its associated structures. Six named pairs of parietal nerves branch from the lumbar plexus bilaterally. They are the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, obturator, and femoral nerves. The lumbosacral trunk and ventral rami of S1-S3 and part of S4 come together to form the sacral plexus, which gives rise to many of the nerves found within the retroperitoneum. The superior and inferior gluteal nerves form from the sacral plexus bilaterally. Also arising from the sacral plexus are right and left lumbar sympathetic trunks, as well as the greater, lesser, and least thoracic splanchnic nerves and four lumbar splanchnic nerves. All of these provide sympathetic innervation to abdominal and pelvic viscera. The pelvic splanchnic nerves provide parasympathetic innervation to structures of the peritoneal cavity. The vagus and splanchnic nerves, along with celiac, superior mesenteric, and aorticorenal ganglia form the autonomic plexuses. These carry sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory (predominantly pain) fibers.[7]

Muscles

Muscles within the retroperitoneum can be organized based on their location. Muscles contributing to the posterior margin of the retroperitoneal space consist largely of the transverse abdominal, psoas, quadratus lumborum, and iliacus. The paraspinous muscles contribute to the medial boundary on either side of the spine, and the abdominal musculature forms the lateral margin. The superior border is formed in part by the diaphragm, while the iliopsoas muscle is the primary muscle contributing to the inferior border.[8]

Surgical Considerations

The treatment of most conditions involving the retroperitoneum requires surgical intervention. As such, a thorough understanding of retroperitoneal anatomy is vital for surgery involving this area. Complications may arise from inadvertent damage to structures located within the retroperitoneum during surgical manipulation or instrumentation.[9] An important consideration in any surgical procedure is gaining access to and achieving proper exposure of the structures in the area of the operation. The Kocher maneuver is a technique that enables access to the retroperitoneum and visualization of structures such as the aorta, inferior vena cava, duodenum, and pancreas. It is performed by first identifying the duodenum, and then making an incision in the peritoneum along its immediate lateral (right) aspect, allowing the duodenum and head of the pancreas to be separated from their peritoneal attachments and reflected 180 degrees medially (to the patient's left) to gain access to retroperitoneal structures.[10] If greater exposure is required, the incision can then be extended caudally along the white line of Toldt, allowing the ascending colon to be reflected medially and more access to the more inferiorly lying retroperitoneal structures. This approach is known as an extended Kocher maneuver and is part of another more extensive technique called the Cattell-Braasch maneuver. It is performed with the steps outlined above with the addition of dissecting the small bowel mesentery cephalad to the Ligament of Treitz in an avascular plane along the inferior mesenteric vein which allows the entire right colon and small bowel to be swung medially out of the abdomen and complete exposure of the retroperitoneal structures.[11][12]

Clinical Significance

Retroperitoneal fibrosis is an uncommon collagen vascular disorder. It is the result of a fibrotic reaction within the retroperitoneum, and its cause is not well understood. It has correlations with both benign and malignant conditions, certain medications, and idiopathic cases, which have also been described. Patients will often present initially with symptoms of ureteric obstruction. Reportedly CT or MRI are of equal value in diagnosis. Imaging typically shows contrast-enhancing fibrosis encasing the structures of the retroperitoneum resulting in obstruction and displacement of the ureters or vascular structures. An underlying cause remains unfound in over 70% of cases. Treatment and outcomes vary and are dependent upon etiology and the degree of obstruction.[13]

The retroperitoneum can occasionally be a site of significant bleeding, usually after trauma, surgical intervention, or even spontaneously in patients with vascular lesions (e.g., abdominal aortic aneurysm) or those treated with anticoagulation therapy. Presentation varies based on etiology. Symptoms can include hypotension, tachycardia, ecchymoses in the affected areas, fatigue, hematuria, and flank or back pain. Computed tomography of the abdomen is the diagnostic imaging of choice. Management of retroperitoneal hematoma is almost always MEDICAL, with resuscitation, blood transfusions, and reversal of anticoagulation as necessary.[14]

Media

References

Tirkes T, Sandrasegaran K, Patel AA, Hollar MA, Tejada JG, Tann M, Akisik FM, Lappas JC. Peritoneal and retroperitoneal anatomy and its relevance for cross-sectional imaging. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2012 Mar-Apr:32(2):437-51. doi: 10.1148/rg.322115032. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22411941]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVesselle HJ, Miraldi FD. FDG PET of the retroperitoneum: normal anatomy, variants, pathologic conditions, and strategies to avoid diagnostic pitfalls. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1998 Jul-Aug:18(4):805-23; discussion 823-4 [PubMed PMID: 9672967]

Rajiah P, Sinha R, Cuevas C, Dubinsky TJ, Bush WH Jr, Kolokythas O. Imaging of uncommon retroperitoneal masses. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2011 Jul-Aug:31(4):949-76. doi: 10.1148/rg.314095132. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21768233]

Selçuk İ, Ersak B, Tatar İ, Güngör T, Huri E. Basic clinical retroperitoneal anatomy for pelvic surgeons. Turkish journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Dec:15(4):259-269. doi: 10.4274/tjod.88614. Epub 2019 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 30693143]

Stallard DJ, Tu RK, Gould MJ, Pozniak MA, Pettersen JC. Minor vascular anatomy of the abdomen and pelvis: a CT atlas. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1994 May:14(3):493-513 [PubMed PMID: 8066265]

Mirilas P, Skandalakis JE. Surgical anatomy of the retroperitoneal spaces, Part III: Retroperitoneal blood vessels and lymphatics. The American surgeon. 2010 Feb:76(2):139-44 [PubMed PMID: 20336888]

Mirilas P, Skandalakis JE. Surgical anatomy of the retroperitoneal spaces, Part IV: retroperitoneal nerves. The American surgeon. 2010 Mar:76(3):253-62 [PubMed PMID: 20349652]

Strauss DC, Hayes AJ, Thomas JM. Retroperitoneal tumours: review of management. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2011 May:93(4):275-80. doi: 10.1308/003588411X571944. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21944791]

Mirilas P, Skandalakis JE. Surgical anatomy of the retroperitoneal spaces, Part V: Surgical applications and complications. The American surgeon. 2010 Apr:76(4):358-64 [PubMed PMID: 20420243]

Song YJ, Suh DS, Kim KH, Na YJ, Lim MC, Park SY. Suprarenal lymph node dissection by the Kocher maneuver in the surgical management of ovarian cancer. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2019 Mar:29(3):647-648. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2018-000093. Epub 2019 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 30733277]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKitahara M, Ohata T, Yamada Y, Yamana F, Nakahira S. The Cattell-Braasch maneuver might be a good option for a huge abdominal aortic aneurysm. Journal of vascular surgery cases and innovative techniques. 2019 Mar:5(1):35-37. doi: 10.1016/j.jvscit.2018.07.008. Epub 2019 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 30671564]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDel Chiaro M, Segersvärd R, Rangelova E, Coppola A, Scandavini CM, Ansorge C, Verbeke C, Blomberg J. Cattell-Braasch Maneuver Combined with Artery-First Approach for Superior Mesenteric-Portal Vein Resection During Pancreatectomy. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2015 Dec:19(12):2264-8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2958-1. Epub 2015 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 26423804]

Cronin CG, Lohan DG, Blake MA, Roche C, McCarthy P, Murphy JM. Retroperitoneal fibrosis: a review of clinical features and imaging findings. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2008 Aug:191(2):423-31. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3629. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18647912]

Kasotakis G. Retroperitoneal and rectus sheath hematomas. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2014 Feb:94(1):71-6. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2013.10.007. Epub 2013 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 24267499]