Introduction

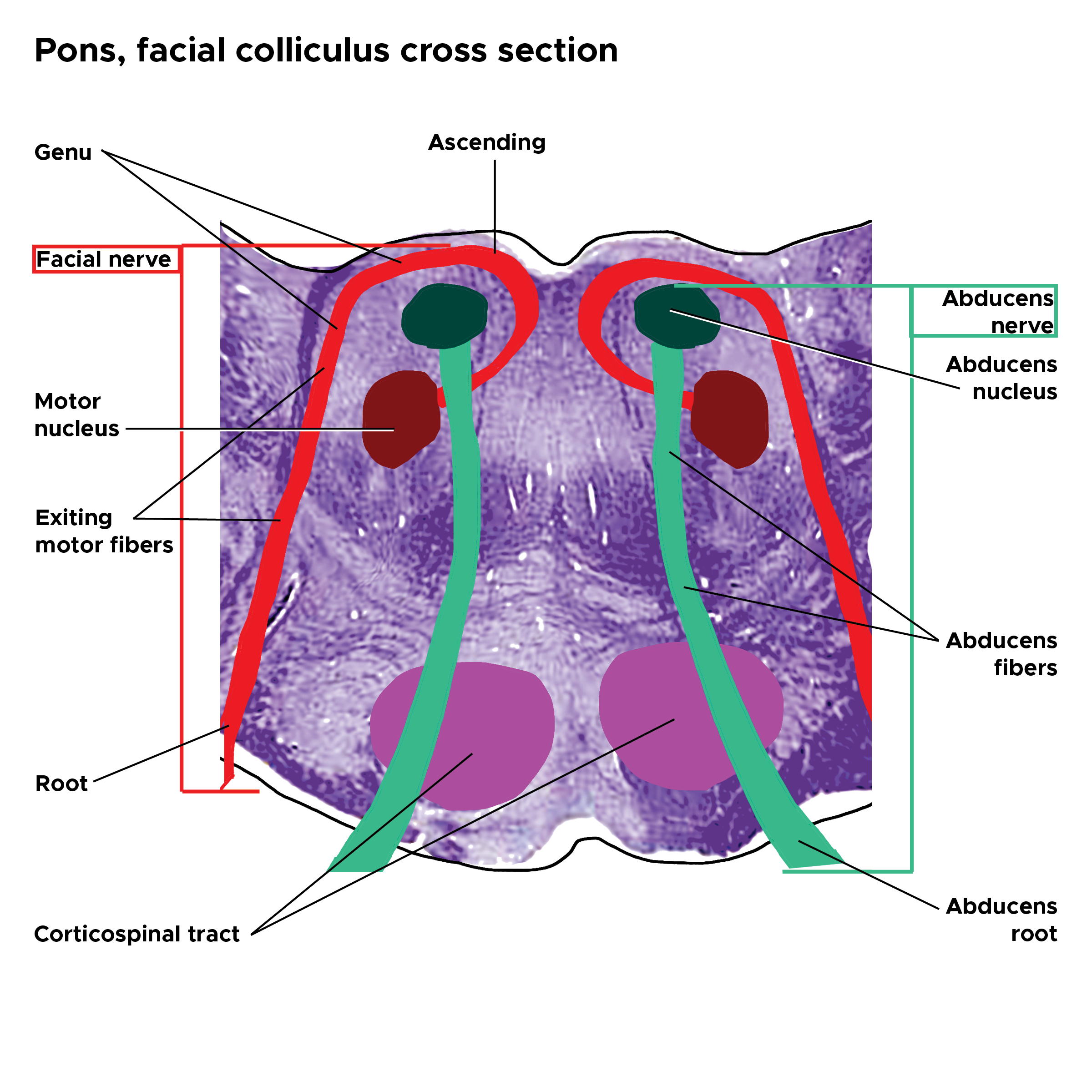

The facial colliculus is a unique feature in the pons that houses the abducens nucleus and the facial motor fibers. This distinctive interaction between the 2 cranial nerves leads to multilevel neurological dysfunctions when there is a lesion of the facial colliculus (see Image. Pons Facial Colliculus Cross Section).

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

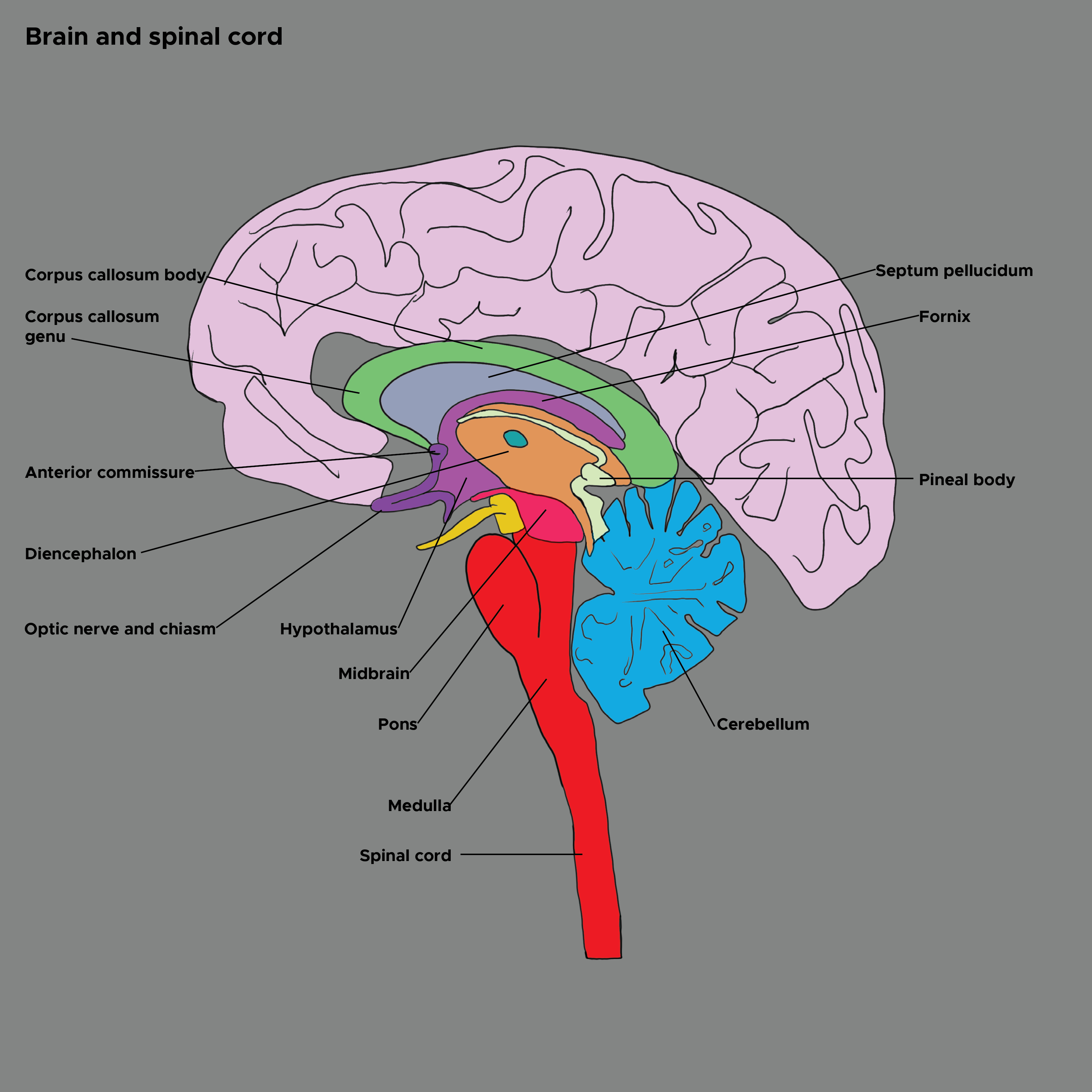

Within the floor of the fourth ventricle, also known as the rhomboid fossa, the facial colliculus can be found laterally to the median sulcus, which symmetrically divides the floor into the right and left halves. The facial colliculus is formed by the facial branchial motor nerve fibers (cranial nerve VII), which turn and loop over the ipsilateral abducens nucleus (cranial nerve VI). The abducens nucleus is located in the dorsal aspect of the caudal pons towards the midline, whereas the facial nucleus is located deeper within the tegmentum of the caudal pons. The loop around CN VI forms a dorsal enlargement, and this observed bump serves as an essential landmark of the floor of the fourth ventricle (see Image. Brain Stem, Labels).[1]

Embryology

Abducens Nerve

In the developing pons, the nucleus of CN VI is identifiable as a group of cells in approximately 20 weeks of gestation. The growth of the nucleus comprising motor neurons and interneurons increases exponentially between 20 and 43 weeks of gestation.[2]

Facial Nerve

During the fourth week of gestation, the chorda tympani nerve arises rostrally from the facial nerve and travels ventrally to the first pharyngeal pouch. By the end of week 5, the motor nucleus of CN VII, developing from the second pharyngeal arch, can be identified in the area of the metencephalon, which later develops into the pons. Between 5 and 6 weeks, the geniculate ganglion and the intermediate nerve begin to develop. The intermediate nerve can be identified as a separate nerve approximately in 7 weeks of gestation. After projecting dorsomedially towards the abducens nucleus, the facial nerve fibers ascend approximately 2 millimeters to loop over the abducens nucleus. The facial nerve fibers subsequently travel between the facial nucleus and the spinal trigeminal nucleus of the cranial nerve 5.[1][3][4]

The onset of myelination of CN VI and VII motor roots is observable as early as 17 weeks of gestation.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The paramedian branches of the basilar artery supply the abducens nucleus. Occlusion of the artery damages CN 6 and, thereby, the lateral rectus muscle that the nerve innervates, resulting in the dysfunctional coordination of horizontal eye movements. The patient experiences the inability to abduct the ipsilateral eye and adduct the contralateral eye. Impaired eye movements are discussed below.[6]

The labyrinthine arteries, which arise from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, supply the facial nucleus and nerve fibers. An occlusion of any of these arteries supplying the facial nerve may result in unilateral facial paralysis, impaired taste, loss of parasympathetic, or diminished somatic sensation.[7]

Nerves

Abducens Nucleus and Nerves

The abducens nucleus comprises motor neurons and interneurons. Projecting from the nucleus, the motor axons of CN VI travel through the tegmental and basal areas of the pons and exit the brainstem at the pontine-medullary junction. The axons then proceed rostrally and pass through the cavernous sinus around the sella turcica, which holds the pituitary gland. From the cavernous sinus, the abducens nerve fibers project through the superior orbital fissure and supply the lateral rectus muscle in the ipsilateral eye. The lateral rectus muscle allows the eye to turn outward toward the ear (abduction). See Image. Brain and Spinal Cord.

Interneurons in the abducens nucleus cross and project rostrally through the contralateral medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) and then synapse with the midbrain's oculomotor nucleus (CN III). The oculomotor nerve fibers innervate the medial rectus muscle, allowing the eye to turn inward toward the nose (adduction). The association of CN VI and III coordinates horizontal eye movements. For example, the right abducens motor nerve innervates the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle to abduct the right eye. At the same time, its interneuron travels through the contralateral MLF to control the adduction of the left medial rectus muscle. The synchronized contraction of the contralateral medial rectus and ipsilateral lateral rectus muscles allows both eyes to look to the right. Different eye movement disorders can be observed based on the location of a lesion along the pathway, including lateral gaze palsy and one-and-a-half syndrome.[8]

Facial Nucleus and Nerves

The facial nerve (CN VII) comprises 2 components: motor and intermediate (also commonly known as nervus intermedius) nerves. The motor root carries somatic motor fibers to facial expression muscles, stapedius, digastric posterior belly, and stylohyoid. The intermediate nerve, not part of the facial colliculus, carries taste, parasympathetic, and somatic sensory fibers. Both motor and intermediate axons exit the brainstem and enter the inner ear through the internal acoustic meatus and the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII). The 2 constituents of CN VII then sharply turn and form a bend known as the geniculate ganglion in the cranial cavity.[1]

Intermediate Nerve

The intermediate facial nerve fibers do not loop around the abducens nucleus but travel through the internal acoustic meatus and meet the facial motor nerve at the geniculate ganglion. The intermediate nerve is composed of parasympathetic and sensory nerves.

Parasympathetic fibers

The superior salivatory nucleus in the pons sends preganglionic parasympathetic fibers to the submandibular or pterygopalatine ganglion. After projecting from the superior salivatory nucleus, some parasympathetic fibers reach the geniculate ganglion and proceed anteriorly as the greater petrosal nerve. The greater petrosal nerve joins the sympathetic called the deep petrosal nerve, and together, they create the pterygoid canal's nerve, also known as the vidian nerve. In the pterygopalatine fossa, only the parasympathetic nerve of the vidian nerve synapses with the pterygopalatine ganglion. The postganglionic parasympathetic fibers proceed from the ganglion and innervate the oral and nasal cavities' lacrimal glands and mucous glands.

The rest of the preganglionic parasympathetic fibers arising from the superior salivatory nucleus travel as part of the chorda tympani nerve. The chorda tympani nerve joins the lingual nerve of the trigeminal nerve (CN V) and continues to travel until it synapses with the submandibular ganglion. The postganglionic parasympathetic fibers innervate the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands. Although the lingual nerve travels with the chorda tympani, it does not synapse with the submandibular ganglion. It carries a general sensation from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

Sensory fibers

The rostral nucleus of the solitary tract, which resides in the medulla, receives taste sensory fibers from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. The chorda tympani, which also delivers preganglionic parasympathetic fibers, carries taste (special sensation) from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

The auricular branches of CN VII innervate the external ear and tympanic membrane and carry general somatic sensation to the spinal nucleus of CN V located in the medulla. The general somatic afferent fibers from the external ear and tympanic membrane pass through the stylomastoid foramen.[9][10]

Motor Nerve

The motor nerve fibers form the facial colliculus by projecting from the facial nucleus and looping around the abducens nucleus. After forming the geniculate ganglion in the cranial cavity, the nerve to the stapedius muscle arises from the motor nerve. It travels in the middle ear to innervate the stapedius muscle. The rest of the motor branches exit the skull through the stylomastoid foramen. The nerve to the posterior belly of digastric and stylohyoid muscles arises before the facial nerve projects to the parotid gland. The temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, and cervical divisions are the nerves of the 5 major muscles of the facial expression. Contracting these muscles is essential for expressing a variety of emotions. Damage to the facial nerve after it passes through the stylomastoid foramen results in a lower motor neuron lesion affecting the ipsilateral side of the face.[11]

Muscles

Lateral and Medial Rectus Muscles

As discussed above, the lateral and medial rectus muscles are associated with the motor neurons and interneurons of CN VI, respectively. The lateral rectus is responsible for the ipsilateral abduction of the eye, whereas the medial rectus is responsible for the contralateral adduction of the eye. Together, they contract and coordinate horizontal eye movements.[8]

Muscles of Facial Expression

The extratemporal facial nerve branches innervate unpaired orbicularis oris and 23 paired muscles.[12] A few significant muscles innervated by each branch of the facial nerve are as follows:

Frontalis

The temporal branch, the uppermost branch of the extratemporal facial nerve, supplies the frontalis muscle on the forehead. The primary function of the frontalis muscle is to raise the eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead.

Orbicularis oculi

The upper portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle is innervated by the temporal branch, whereas the lower portion receives innervation from the zygomatic branch of the facial nerve. The orbicularis oculi muscle around each eye helps close the eyelid and drain tears into the nasolacrimal duct.

Zygomaticus major

The zygomatic branch innervates the muscle. It is one of the major muscles for lifting the angle of the mouth and smiling.

Buccinator

The buccal branch of CN VII innervates the muscle. It is responsible for pulling the cheek against teeth and puckering.

Orbicularis oris

The buccal division innervates the superior portion of the muscle, whereas the inferior portion's innervation comes from the mandibular branch of the facial nerve. The orbicularis oris muscle helps close the mouth and lips.

Platysma

The platysma muscle's nerve supply comes from the facial nerve's cervical branch. The platysma attaches to the neck and the mandible and helps open the mouth and pull down the corners of the lips. It is known as the "fright" muscle.[1][13]

Stapedius

The stapedius muscle, attached to the neck of the stapes bone, is the smallest skeletal muscle in the body. The nerve to stapedius supplies it, which branches off the facial nerve. The primary function of this muscle is to reduce ossicular vibrations and protect the inner ear from getting damaged by loud noises. Damage to the muscle or its nerve can result in hyperacusis (hypersensitivity to normal sounds).[14]

Posterior belly of digastric

The posterior belly of the digastric muscle attaches to the hyoid bone and mastoid process of the temporal bone and receives innervation from the digastric branch of CN VII. Coordinating with the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, it lowers the jaw to open the mouth and elevates the hyoid bone for swallowing.[9]

Stylohyoid

The stylohyoid muscle, which extends from the styloid process of the temporal bone to the hyoid bone, is innervated by the styloid branch of the facial nerve. The stylohyoid muscle pushes the hyoid bone backward and elevates the tongue.[9]

Clinical Significance

The facial colliculus comprises CN VI and VII, so a lesion may lead to multi-level symptoms. CN VI lesions may impair horizontal eye movements, including lateral gaze palsy and one-and-a-half syndrome. One of the significant abnormalities from CN VII damage is Bell palsy.

Lateral Gaze Palsy

A lesion in the abducens nucleus leads to the paralysis of the ipsilateral lateral rectus. Although the contralateral medial rectus muscle function, which CN III innervates, remains intact, interneurons projecting from the damaged CN VI nucleus can no longer send proper signals through the contralateral MLF to the CN III nucleus. As a result, horizontal eye movements cannot coordinate when both eyes attempt to gaze towards the side of the lesion. For example, if the right nucleus of CN VI is damaged, the right CN VI fibers projecting to the right lateral rectus muscle be impaired. Since the left CN III nucleus and its nerves are not damaged, there is no problem contracting the left medial rectus muscle when CN III is activated, and CN VI is not involved. In this example, the lesion of the right nucleus of CN VI impairs the left MLF that projects to the left CN III nucleus, and thus, the left CN III nerve cannot stimulate the contraction of the left medial rectus muscle. Ultimately, horizontal eye movements become disrupted, and both eyes look straight ahead when instructing the patient to turn their gaze to the right. The patient has no problem gazing to the left.

One-and-a-Half Syndrome

Suppose a lesion in the dorsal pontine tegmentum is more extensive than the size of the CN VI nucleus and damages both the ipsilateral abducens nucleus and MLF. In that case, the ipsilateral lateral rectus and bilateral medial rectus muscles are impaired. CN VI fibers arise from the ipsilateral CN VI nucleus and travel to the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle. In contrast, the interneuron fibers from the ipsilateral nucleus cross the midline and project through the contralateral MLF and synapse to the contralateral CN III nucleus. The ipsilateral MLF, to which the contralateral CN VI fibers project, is responsible for the synapse on the ipsilateral CN III nucleus, which innervates the ipsilateral medial rectus muscle. For example, when the lesion affects both the right CN VI nucleus and MLF fibers, the right lateral rectus and left medial rectus muscles associated with the right CN VI fibers are impaired. The right medial rectus muscle, innervated by the right CN III that can no longer receive signals from the right damaged MLF, also be impaired. As a result, when the examiner asks a patient to look to the right, the patient seems to be looking straight ahead. When instructing a patient to look to the left, the patient’s left eye looks to the side, whereas the right eye cannot move to the left and look straight ahead.

Bell Palsy

Because the facial motor nerve fibers loop over CN VI in the dorsal aspect of the caudal pons, damage to the facial colliculus results in the paralysis of the ipsilateral facial muscles, a classical representation of a condition called Bell’s palsy. A patient with Bell’s palsy may experience drooping of the corner of the mouth and upper eyelid. The patient may also be unable to wrinkle his or her forehead and experience overall facial muscle weakness. Because the facial motor and intermediate nerve fibers do not meet until the geniculate ganglion, other responses such as taste, parasympathetic, and somatic sensation might still be intact.[15]

Hyperacusis

Paralysis of the stapedius muscle due to the injured facial nerve may lead to uninhibited movements of the stapes and ultimately to an excessive acuteness to hearing.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Takezawa K, Townsend G, Ghabriel M. The facial nerve: anatomy and associated disorders for oral health professionals. Odontology. 2018 Apr:106(2):103-116. doi: 10.1007/s10266-017-0330-5. Epub 2017 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 29243182]

Yamaguchi K, Honma K. Development of the human abducens nucleus: a morphometric study. Brain & development. 2012 Oct:34(9):712-8. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.12.009. Epub 2012 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 22269150]

Sataloff RT, Selber JC. Phylogeny and embryology of the facial nerve and related structures. Part II: Embryology. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2003 Oct:82(10):764-6, 769-72, 774 passim [PubMed PMID: 14606174]

Casale J, Giwa AO. Embryology, Branchial Arches. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860722]

Hatta T, Satow F, Hatta J, Hashimoto R, Udagawa J, Matsumoto A, Otani H. Development of the pons in human fetuses. Congenital anomalies. 2007 Jun:47(2):63-7 [PubMed PMID: 17504389]

Gates P. The rule of 4 of the brainstem: a simplified method for understanding brainstem anatomy and brainstem vascular syndromes for the non-neurologist. Internal medicine journal. 2005 Apr:35(4):263-6 [PubMed PMID: 15836511]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFogwe DT, Sandhu DS, Goyal A, Mesfin FB. Neuroanatomy, Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Arteries. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846315]

Nguyen V, Reddy V, Varacallo M. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 6 (Abducens). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613463]

Dulak D, Naqvi IA. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 7 (Facial). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252375]

Sanders RD. The Trigeminal (V) and Facial (VII) Cranial Nerves: Head and Face Sensation and Movement. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township)). 2010 Jan:7(1):13-6 [PubMed PMID: 20386632]

Monkhouse WS. The anatomy of the facial nerve. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 1990 Oct:69(10):677-83, 686-7 [PubMed PMID: 2286163]

Myckatyn TM, Mackinnon SE. A review of facial nerve anatomy. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2004 Feb:18(1):5-12. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-823118. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20574465]

Tong J, Lopez MJ, Patel BC. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Orbicularis Oculi Muscle. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722936]

Prasad KC, Azeem Mohiyuddin SM, Anjali PK, Harshita TR, Indu Varsha G, Brindha HS. Microsurgical Anatomy of Stapedius Muscle: Anatomy Revisited, Redefined with Potential Impact in Surgeries. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2019 Mar:71(1):14-18. doi: 10.1007/s12070-018-1510-5. Epub 2018 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 30906706]

Somasundara D, Sullivan F. Management of Bell's palsy. Australian prescriber. 2017 Jun:40(3):94-97. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2017.030. Epub 2017 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 28798513]