Introduction

Imperforate anus or anal atresia is a congenital anorectal malformation (ARM) where a normal anal opening is absent at birth. ARMs comprise of a broad spectrum of defects ranging from minor (e.g., membranous covering) to complex cloacal malformations involving the urinary and genital tracts as well.[1] Thus prognosis may vary greatly. ARMs commonly have associated maldevelopment of the pelvic muscles, including the external anal sphincter and nerves[2]. About half of patients with ARM also have anomalies of other organ systems. These most commonly involve genitourinary and musculoskeletal systems.[3][4] Delayed diagnosis may happen in one out of five neonates, despite routine postpartum evaluation. Such a delay may increase morbidity and mortality.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact etiology of anorectal malformations is unknown and is likely multifactorial. Positive family history occurs in approximately 1.4% of cases.[5] An autosomal dominant mode of inheritance occurs in specific syndromes, such as Currarino syndrome, Townes-Brock syndrome, and Pallister-Hall syndrome.[1] Research has noted an increased incidence with trisomy 13, 18, and 21.[3] About half of patients with ARM are found to have associated anomalies, and the risk of anomalies increases with a higher level of ARM.[4] These most commonly include genitourinary anomalies, vertebral/spinal cord anomalies, craniofacial anomalies, cardiovascular anomalies, spinal cord anomalies, and other gastrointestinal anomalies.[6][5][3] Reports show a consistently increased risk of anorectal malformation with paternal smoking, maternal overweight, obesity, and diabetes.[7]

Imperforate anus is commonly associated with other congenital abnormalities grouped as VACTERL Syndrome/Associations, which stands for:

- Vertebral defects – e.g., small hypoplastic vertebrae or hemivertebra

- Anal defects – anal atresia/imperforate anus

- Cardiac defects – e.g., ventricular septal defects, atrial septal defects, or tetralogy of Fallot

- Tracheoesophageal fistula

- Renal defects – Complete or partial renal genesis (either unilateral or bilateral), other genitourinary system anomalies

- Limb defects – missing or displaced digits, polydactyly, or syndactyly (i.e., webbed or fused fingers or toes)

To diagnose VACTERL/VACTER Syndrome, at least 3 of defects must be present.[8]

Other syndromes that may be commonly associated with ARMs include MURCS (Mullerian duct aplasia, renal aplasia, and cervicothoracic somite dysplasia), OEIS (omphalocele, exstrophy, imperforate anus, and spinal defects).[1]

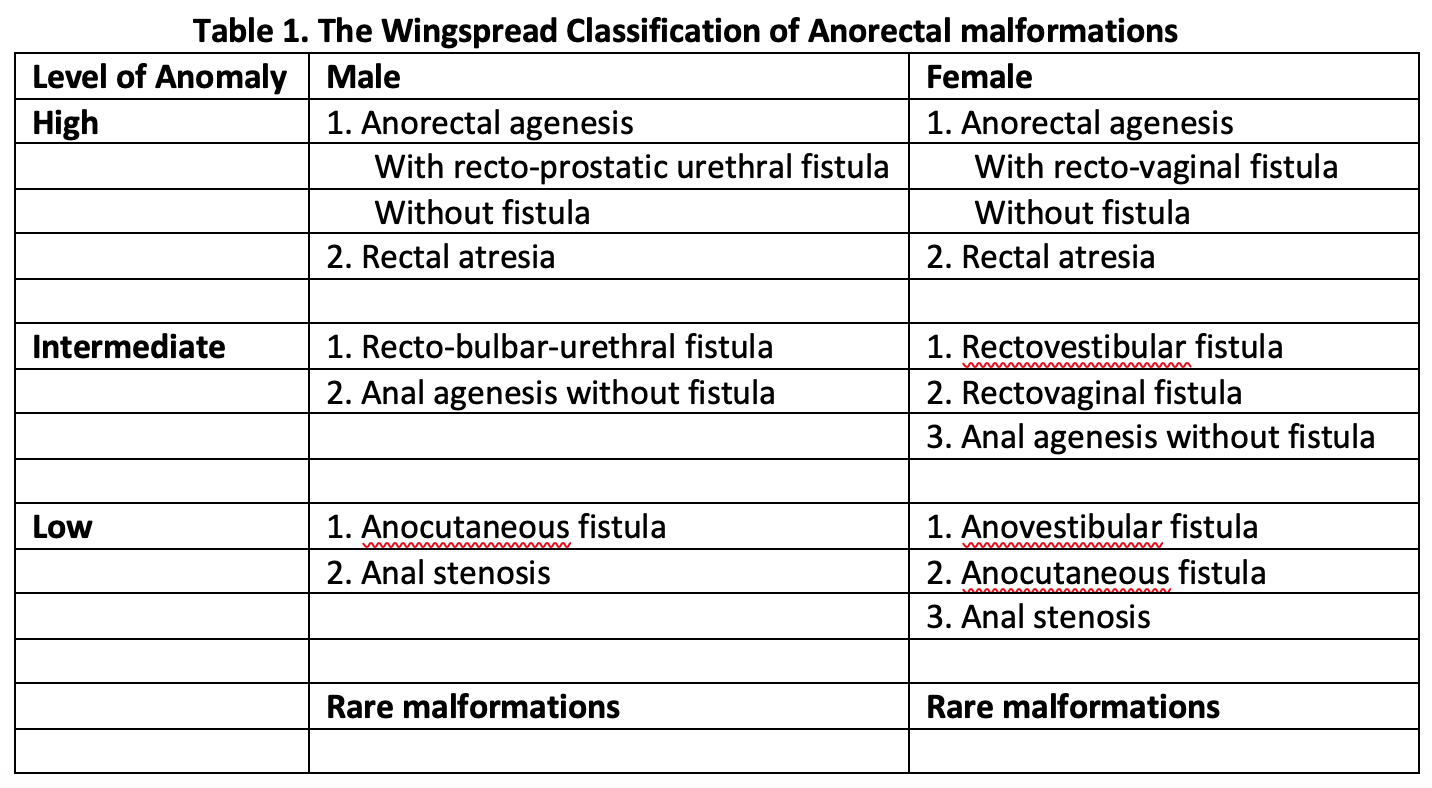

Classification

Anorectal malformations have traditionally divided into high, intermediate, or low malformation based on the relationship of end of the rectal pouch to the level of levator ani muscle (Wingspread Classification, 1984).[9] This classification had a separate group of anomalies for males and females, with special categories of cloacal and rare malformations (Table 1, media item 2). The Wingspread classification was in wide use and directed the choice of surgical approach, with a simple perineal approach considered for low malformations and complex surgeries needed for high malformations.

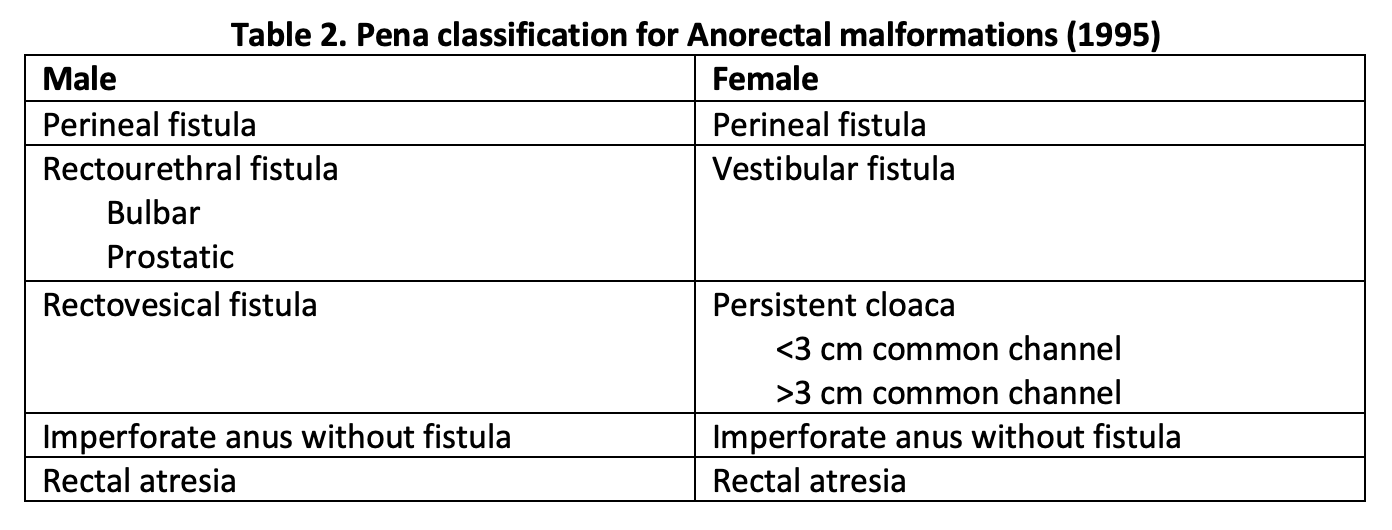

However, Pena et al., with his extensive experience in posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP), found that fistula type greatly influenced outcomes in these patients. In 1995, he described a new classification system based on the type of fistula present.[10] Details of the Pena classification appear in Table 2. The location and type of fistula help guide the operative approach and the extent of mobilization needed for pulling through the blind pouch. He also introduced new follow-up criteria including fecal soiling, constipation, voluntary bowel movement, and complete fecal continence.

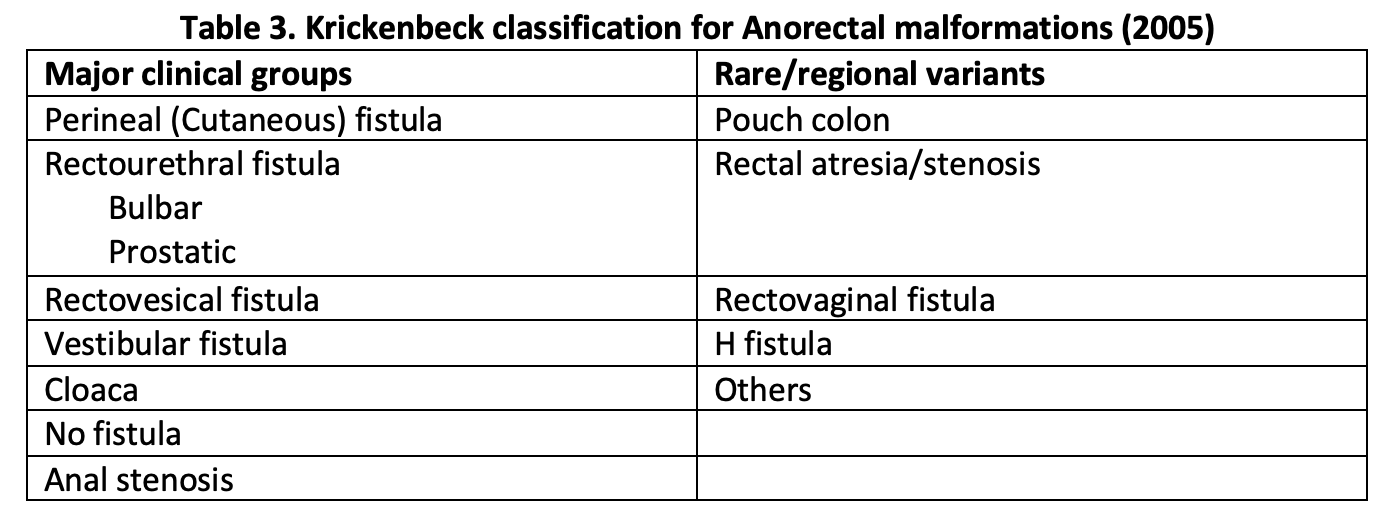

In 2005, the Krickenbeck group proposed a modification of this classification to allow for comparison of outcome data of patients with ARMs undergoing different surgeries. This classification system provides standards for the classification of diagnosis, surgical procedures, and postoperative results.[9] The details of the Krickenbeck classification system for ARM diagnosis appear in Table 3.

Epidemiology

Imperforate anus has an incidence estimated to be 1 in 5000 births in the U.S. Males have a slightly higher incidence than females[1]. Rectourethral fistula is the most common defect in males and rectovestibular fistula in females.[1]

Pathophysiology

Anorectal malformations occur during the 8 to 12 weeks of fetal gestation due to the failure to complete the development of the hindgut. There is impaired septation, and the cloacal membrane is usually found to be short in its dorsal part; thus, the hindgut retains its attachment to the sinus urogenitalis.[11]

History and Physical

Anal atresia should be suspected clinically at birth during routine postpartum evaluation or shortly thereafter when the newborn fails to have a bowel movement within 24 hours after birth (i.e., failure to pass meconium). Patients may present with abdominal distension. Sometimes meconium may emerge from fistula in the perineum or from the urethra.

A thorough examination of the perineum should take place at birth, and after 24 hours. These may reveal a lack of anal opening or a small depression (called an anal pit). The presence of a small orifice, not at the normal position of the anus, may indicate a perineal fistula. This defect is usually present anterior to the anal sphincter complex. There may be a fistula to the genitourinary tract if stool is noted coming out of the urethra or vagina instead of the anus. However, it may take more than 24 hours for the fistula to reveal itself because significant pressure is needed to force meconium through the fistulous opening. Examination of urine is essential in male newborns to look for evidence of meconium. In a female child with ARM, close inspection of the vestibule (the area between the labia) is necessary. The normal vestibule has two openings, urethra anteriorly and vagina posteriorly. The presence of a single opening indicates persistent cloaca, and the presence of three openings indicates a vestibular fistula. The presence of two openings in the vestibule with absent anus indicates an underlying rectovaginal fistula or a blind-ending rectum. Patients with high anorectal malformations may have a flat "bottom" or flat perineum, and absent midline gluteal fold. These indicate underdeveloped musculature in the perineum or sacral deformities, and such patients tend to have associated poor prognosis for achieving bowel control.

Patients with anorectal malformation have a high incidence of associated anomalies, and examination should be done to detect these.[4] It is significant to recognize if there are other specific findings on the physical exam that could be related to a particular syndrome, e.g., vertebral defects, abnormalities of the radial bone in the arms. A passage of nasogastric tube should be done to evaluate for esophageal atresia. The clinician should examine the umbilical cord at birth; the presence of a single umbilical artery may suggest underlying renal malformation.[12] A cardiovascular examination may uncover a murmur.

Evaluation

Diagnostic evaluation of these patients should focus on delineating the level and complexity of anorectal malformation and identification of any associated defects. These patients have a high incidence of associated genitourinary and musculoskeletal (usually sacral) malformations, especially if a high anorectal malformation is present. Evaluation of vertebral and spinal cord defects is essential. The approach to these patients involves an interprofessional team, including pediatricians, neonatologists, pediatric surgery, and pediatric urology.

Ultrasound of abdomen and pelvis is a valuable screening modality for the diagnosis of associated gastrointestinal and genitourinary anomalies and should take place early. Ultrasound of the perineum helps estimate the distance between the rectal pouch and the perineum.

Once abdominal distension has developed, a lateral film radiograph in prone position should be done to determine the location of the distal bowel air bubble from the anal dimple (marked by the placement of a lead marker). A distance of less than 1 cm usually indicates a low defect, and greater than 1 cm distance may indicate a high defect.[13] Traditionally, invertogram (i.e., radiograph with infant held upside down) has been used to indicate this pouch-perineum distance. But the baby is usually uncomfortable in this position, and incessant crying may lead to contraction of puborectalis sling and obscuration of the distal rectal pouch. For this reason, a prone cross-lateral view is now preferable to an invertogram. Invertogram has been shown to be highly inaccurate for assessment of pouch position.[14]

A plain radiograph of the entire spine, including the sacrum and both iliac wing, should be done to detect vertebral anomalies and sacrum adequacy. X-rays of the extremities are necessary if there are abnormal findings on the physical exam. Evaluation of any associated cardiac defects should take place with an echocardiogram.

In an infant where diverting colostomy has occurred for complex ARM (esp. cloaca), a contrast study of distal colon (distal colostography) is beneficial in identifying the real height of the distal rectal pouch and its fistulous connection. It needs an injection of water-soluble contrast via distal mucous fistula under pressure. If there is a connection to the urinary bladder, a voiding cystourethrogram may be done at the same time to delineate the anatomy of the urinary bladder and any associated vesicoureteric reflux. Experienced hands should perform this procedure; there have been reports of bowel perforation as a complication.[15] Although very accurate in determining the location of the rectal pouch and fistula, the distal colostogram does not provide any information regarding the anatomy of pelvic musculature.

An MRI of the pelvis is beneficial for delineating the anatomy of pelvic floor muscles, the location of the rectal pouch, and any fistula. Recent advances in MRI imaging have allowed high-resolution imaging of pelvic structures. These findings may significantly influence the planned surgical approach. MRI may also serve to evaluate for a tethered cord or abnormal attachment of the spinal cord to the vertebrate, as well as for the assessment of anatomical development after surgical correction of ARM.[16]

Treatment / Management

Upon diagnosing a newborn with ARMs, initial management should focus on hydration and avoidance of sepsis. Surgical intervention is not needed emergently, and newborn should undergo thorough diagnostic evaluation in the first 24 to 36 hours of life.[1] There should be the placement of intravenous lines for fluids and antibiotics, and a nasogastric tube inserted for stomach decompression, and to avoid the possibility of vomiting and aspiration.

The patient may need to undergo a diverting colostomy or surgical repair. This decision has its basis on the complexity of anorectal malformation, associated anomalies, and any metabolic abnormalities developing soon after birth.[17] Generally speaking, a low lying simple ARM may undergo primary anoplasty, and a high or complex malformation would need initial diverting colostomy followed by definitive surgical repair 4 to 8 weeks later.

When a diverting colostomy is necessary, a descending or sigmoid colostomy is preferred and brought out through the left lower quadrant of the abdomen. Performance of colostomy results in diversion of stool stream and allows for delayed repair as the urgent concern of bowel obstruction and/or sepsis from fistula has been addressed. It also provides for a more accurate diagnosis of the level of the rectal pouch as a contrast pouchogram is not possible through the distal limb of colostomy.

Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) is currently the gold standard procedure for the repair of most ARMs. Pena et al. described PSARP.[18] This procedure involves repair of ARM by perineal approach, although, for higher defects, mobilization of the distal rectal pouch may be necessary, via the abdominal route. A strict midline incision from the sacrum to the anal dimple spares neurovascular structures while dividing skin and underlying muscular structures. Further technical details are outside the scope of this chapter and are available through the provided reference.[18] It may be done in 1 stage (without colostomy) or three stages (colostomy, PSARP, and colostomy closure). In newborns who underwent diverting colostomy, the definitive repair is done after 4 to 8 weeks if the newborn has been growing well with proper nutrition and the absence of sepsis. One stage repair is possible by experienced hands in patients with low anomalies and selected high anomalies.[17] These procedures require an experienced surgeon in high volume facilities for the best result.[19]

Immediate postoperative care usually deals with pain control and need to keep a urinary catheter (Foley or suprapubic) in some patients undergoing genitourinary repair. After two weeks of repair, patients need to undergo anal dilation to avoid stricture at the level of the skin. Over the subsequent 6 to 12 months, once achieving adequate dilation and skin stricture has not developed, it is possible to close the colostomy. Patients usually struggle with perineal skin maceration and diaper rash after colostomy closure as the skin gets exposed to multiple bowel movements for the first time. Education of parents regarding anal dilations and management of diaper rash is vital to obtain good results. It takes a few months for patients to achieve a stable pattern of bowel movements.

Differential Diagnosis

Most patients with imperforate anus receive a diagnosis early in the newborn period, but few with complex malformation and perineal fistulas may evade early detection. Furthermore, anorectal malformations constitute a full spectrum of anatomical anomalies varying from simple membranous covering over anal dimple to complex cloacal defects with fistulous disease. These patients require management by experienced practitioners in tertiary care centers. Evaluation for associated anomalies is essential, and full diagnostic workup is necessary as detailed previously.

Prognosis

The complexity of anorectal malformations and associated anomalies usually determines the quality of life. Patients with low lesions are more likely to develop continence. Most patients will develop either constipation or incontinence and need to be managed with laxative or dietary modifications accordingly. These patients require follow-up for their lifetime.

Complications

Failure to diagnose this condition early may result in newborn developing dehydration, vomiting, aspiration, and sepsis. Surgical site infection wound dehiscence, and urinary tract infection can accompany most abdominal surgeries. Postsurgical complications specific to surgical repair of ARMs include recurrent or persistent fistula, anal stenosis, stricture of other reconstructed structures, and rectal prolapse.[20] The complexity of malformations and associated anomalies (e.g., vertebral anomalies) usually determine long-term results. Those with significant vertebral anomalies, spinal cord tethering, or complex ARMs may be disabled for the rest of their lives.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Anorectal malformations constitute a full spectrum of abnormalities with the need for lifelong follow-up even after a successful repair. These anomalies must be detected early, preferably in the delivery room. Early involvement of neonatologists and pediatric surgeons is vital for treatment planning and timely intervention. Complex repair may need multiple specialists and teams (pediatric surgery, urology, gynecology) working at the same time, operating as a cohesive interprofessional team. Nursing care with experienced neonatal specialty nurses is vital before and after surgery, and they should report any findings or concerns to the clinician managing the case. Parents need to understand the disorder and available treatment options. Because ARMs may occur in patients with VACTERL complex, a thorough workup of the infant is necessary before any surgery. If a temporary colostomy is required, the stoma nurse should educate the parents on its management and its duration. The frequent anal dilatations and progressive perineal skin maceration do take a toll on the patient and the family. Nurses should regularly check the perineum for fecal soilage and keep it clean. Finally, imperforate anus also creates parental anxiety, and a mental health nurse consult may be a strong recommendation.

Care coordination and parent education are a significant determinant of long term outcome after discharge; this is where an interprofessional team, as outlined above, must continue to communicate and manage the patient, potentially for life. Each discipline must share and have access to the same findings and data for the patient to perform their duties and achieve optimal patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Levitt MA, Peña A. Anorectal malformations. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2007 Jul 26:2():33 [PubMed PMID: 17651510]

Watanabe Y, Ando H, Seo T, Kaneko K, Katsuno S, Shinohara T, Mori K, Toriwaki J. Three-dimensional image reconstruction of an anorectal malformation with multidetector-row helical computed tomography technology. Pediatric surgery international. 2003 May:19(3):167-71 [PubMed PMID: 12768311]

Cho S, Moore SP, Fangman T. One hundred three consecutive patients with anorectal malformations and their associated anomalies. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2001 May:155(5):587-91 [PubMed PMID: 11343503]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEndo M, Hayashi A, Ishihara M, Maie M, Nagasaki A, Nishi T, Saeki M. Analysis of 1,992 patients with anorectal malformations over the past two decades in Japan. Steering Committee of Japanese Study Group of Anorectal Anomalies. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1999 Mar:34(3):435-41 [PubMed PMID: 10211649]

Falcone RA Jr, Levitt MA, Peña A, Bates M. Increased heritability of certain types of anorectal malformations. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2007 Jan:42(1):124-7; discussion 127-8 [PubMed PMID: 17208552]

Wijers CH, van Rooij IA, Marcelis CL, Brunner HG, de Blaauw I, Roeleveld N. Genetic and nongenetic etiology of nonsyndromic anorectal malformations: a systematic review. Birth defects research. Part C, Embryo today : reviews. 2014 Dec:102(4):382-400. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21068. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25546370]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZwink N, Jenetzky E, Brenner H. Parental risk factors and anorectal malformations: systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2011 May 17:6():25. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-25. Epub 2011 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 21586115]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSolomon BD. VACTERL/VATER Association. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2011 Aug 16:6():56. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-56. Epub 2011 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 21846383]

Holschneider A, Hutson J, Peña A, Beket E, Chatterjee S, Coran A, Davies M, Georgeson K, Grosfeld J, Gupta D, Iwai N, Kluth D, Martucciello G, Moore S, Rintala R, Smith ED, Sripathi DV, Stephens D, Sen S, Ure B, Grasshoff S, Boemers T, Murphy F, Söylet Y, Dübbers M, Kunst M. Preliminary report on the International Conference for the Development of Standards for the Treatment of Anorectal Malformations. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2005 Oct:40(10):1521-6 [PubMed PMID: 16226976]

Peña A. Anorectal malformations. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 1995 Feb:4(1):35-47 [PubMed PMID: 7728507]

Kluth D. Embryology of anorectal malformations. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 2010 Aug:19(3):201-8. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2010.03.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20610193]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThummala MR, Raju TN, Langenberg P. Isolated single umbilical artery anomaly and the risk for congenital malformations: a meta-analysis. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1998 Apr:33(4):580-5 [PubMed PMID: 9574755]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShaul DB, Harrison EA. Classification of anorectal malformations--initial approach, diagnostic tests, and colostomy. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 1997 Nov:6(4):187-95 [PubMed PMID: 9368270]

Niedzielski JK. Invertography versus ultrasonography and distal colostography for the determination of bowel-skin distance in children with anorectal malformations. European journal of pediatric surgery : official journal of Austrian Association of Pediatric Surgery ... [et al] = Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie. 2005 Aug:15(4):262-7 [PubMed PMID: 16163592]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceThomeer MG, Devos A, Lequin M, De Graaf N, Meeussen CJ, Meradji M, De Blaauw I, Sloots CE. High resolution MRI for preoperative work-up of neonates with an anorectal malformation: a direct comparison with distal pressure colostography/fistulography. European radiology. 2015 Dec:25(12):3472-9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3786-0. Epub 2015 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 26002129]

Madhusmita, Ghasi RG, Mittal MK, Bagga D. Anorectal malformations: Role of MRI in preoperative evaluation. The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2018 Apr-Jun:28(2):187-194. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_113_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30050242]

Liu G, Yuan J, Geng J, Wang C, Li T. The treatment of high and intermediate anorectal malformations: one stage or three procedures? Journal of pediatric surgery. 2004 Oct:39(10):1466-71 [PubMed PMID: 15486889]

Peña A, Devries PA. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty: important technical considerations and new applications. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1982 Dec:17(6):796-811 [PubMed PMID: 6761417]

Wood RJ, Levitt MA. Anorectal Malformations. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2018 Mar:31(2):61-70. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1609020. Epub 2018 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 29487488]

Versteegh HP, Sutcliffe JR, Sloots CE, Wijnen RM, de Blaauw I. Postoperative complications after reconstructive surgery for cloacal malformations: a systematic review. Techniques in coloproctology. 2015 Apr:19(4):201-7. doi: 10.1007/s10151-015-1265-x. Epub 2015 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 25702171]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence