Introduction

Hip fractures are common injuries, especially seen in the elderly in the emergency setting. It is also seen in young patients who perform in athletics or high-energy trauma. Immediate diagnosis and management are required to prevent threatening joint complications.[1] In the United States, the economic burden of hip fractures is amongst the top 20 expensive diagnoses, with approximately 20 billion dollars spent on the management of this injury.[2][3][4] It is estimated there will be approximately 300,000 cases of hip fractures annually in the United States by the year 2030.[5]

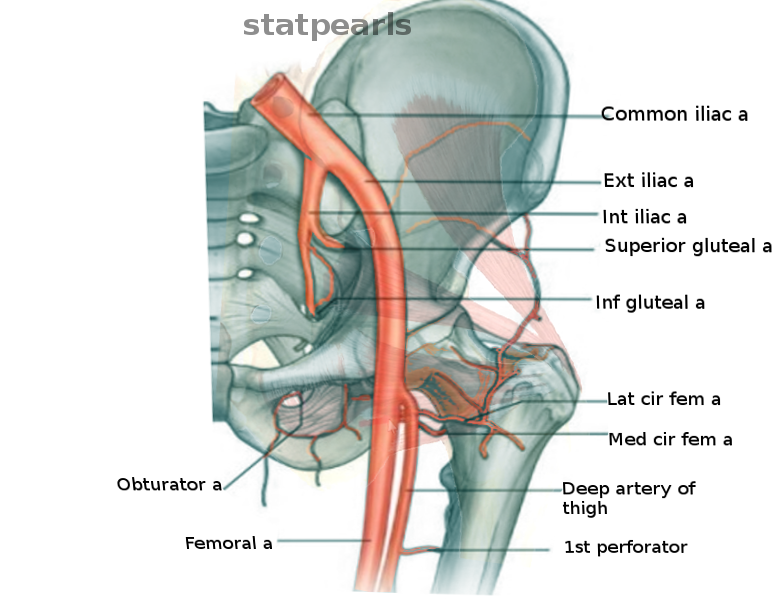

Femoral neck fractures are a specific type of intracapsular hip fracture. The femoral neck connects the femoral shaft with the femoral head. The hip joint is the articulation of the femoral head with the acetabulum. The junctional location makes the femoral neck prone to fracture. The blood supply of the femoral head is an essential consideration in displaced fractures as it runs along the femoral neck.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Femoral neck fractures are associated with low energy falls in the elderly. In younger patients sustaining a femoral neck fracture, the cause is usually secondary to high-energy trauma such as a substantial height or motor vehicle accidents.[6][7] Risk factors for femoral neck fractures include female gender, decreased mobility, and low bone density.[8][9][8]

Epidemiology

There are approximately 1.6 million hip fractures annually. Seventy percent of all hip fractures occur in women. Hip fracture risk increases exponentially with age and is more common in white females.[7][10]

Pathophysiology

The chief source of vascular supply to the femoral head is the medial femoral circumflex artery, which runs under the quadratus femoris. Displaced fractures of the femoral neck put the blood supply at risk, usually tearing the ascending cervical branches that stem off the arterial ring supply formed by the circumflex arteries. This may compromise the healing ability of the fracture, inevitably causing non-union or osteonecrosis.[11] This is most important when considering the younger population that sustains this fracture, for which arthroplasty would be inappropriate.[12] In patients treated via open reduction internal fixation, avascular necrosis is the most common complication.[13]

History and Physical

In the majority of cases, the patient will have had recent trauma. In cases of dementia or cognitive impairment, the history may be scant without the report of any trauma. This is where obtaining an account from the nursing home, or health aids is crucial. Question the nurse aids of any recent falls and change in cognition the past few days. The patient will complain of pain with a decreased range of motion of the hip. In non-displaced fractures, there may be no deformity. However, displaced fractures may present with a shortened and externally rotated lower limb.

The patient history varies depending on the mechanism of injury. The following should be obtained during the history and physical examination:

- Low energy trauma - the mechanism is essential, and the events around the fall should be questioned to rule out any possible syncopal cause for fall.

- High energy trauma - Follow the ATLS (Adult Trauma Life Support) protocol when indicated. Assess for any non-orthopedic emergent injuries first and then ipsilateral injuries, including femur fracture or knee injury. For high vertical falls, inspect the ankle for any abnormalities.

- Important pertinent medical history: Baseline function and activity level, use of ambulatory aids before the injury, blood thinners, history of cancer, pulmonary embolism, and deep venous thrombosis.

Evaluation

The provider should perform a complete neurovascular examination of the affected extremity. The following imagining should be ordered when indicated:

- Plain films: radiographs-anterior-posterior (AP) pelvis, AP and lateral hip, AP and lateral femur, AP and lateral knee.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan - helps better classify the fracture pattern or delineate a subtle fracture line. It is part of the trauma assessment and can be extended to include the femoral neck.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) - not generally used in the acute setting but may be used to evaluate for femoral neck stress fractures.

Medical assessment should include basic labs (complete blood count, basal metabolic panel, and prothrombin/international normalized ratio, if applicable) as well as a chest radiograph and electrocardiogram (EKG). Elderly patients with known or suspected cardiac disease may benefit from preoperatively cardiology evaluation. Preoperative medical optimization is vital in the geriatric population.

There are many classifications for femoral neck fracture, including the most common clinical classifications by Garden and Pauwel, which includes the following[12][14]

The Garden Classification

- Type I: Incomplete fracture - valgus impacted-non displaced

- Type II: Complete fracture - nondisplaced

- Type III: Complete fracture - partial displaced

- Type IV: Complete fracture - fully displaced

The Garden classification is the most used system used to communicate the type of fracture. For treatment, it is often simplified into nondisplaced (Type 1 and Type 2) versus displaced (Type 3 and Type 4).[14]

Pauwel Classification

The Pauwel classification also includes the inclination angle of the fracture line relative to the horizontal. Higher angles and more vertical fractures exhibit greater instability due to higher shear force. These fractures also have a higher risk of osteonecrosis postoperatively.

- Type I less than 30 degrees

- Type II 30 to 50 degrees

- Type III greater than 50 degrees

Treatment / Management

Non-operative

Non-operative management for these fractures is rarely the treatment course. It is only potentially useful for non-ambulatory, comfort care, or extremely high-risk patients.

Operative

Young patients with femoral neck fractures will require treatment with emergent open reduction internal fixation.[6][15] Vertically oriented fractures such a Pauwel III type fractures are more common in younger and high-energy trauma patients. A sliding hip screw is biomechanically more stable for these fracture patterns. With displaced fractures in younger patients, the goal is to achieve anatomic reduction through emergent open-reduction internal fixation.[15](A1)

Non-displaced fractures are treated typically with percutaneous cannulated screws or a sliding hip screw. However, there a higher rate of avascular necrosis (AVN) with the use of a sliding hip screw (9%) compared to cannulated screws (4%).[16](A1)

With displaced fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients, the treatment depends on the patient's baseline activity level and age. Less active individuals may receive a hemiarthroplasty.[17] More active individuals are treated with total hip arthroplasty. Total hip arthroplasty is a more resilient procedure, but it also carries an increased risk of dislocation when compared to a hemiarthroplasty.[18][19][15](A1)

Summary of Operative Methods

Young Patients (less than 60)

- Open-reduction internal fixation

Elderly Patients

Non-displaced

- Percutaneous cannulated screws or sliding hip screw

Displaced

- Hemiarthroplasty-less active patients

- Total hip arthroplasty-active patients

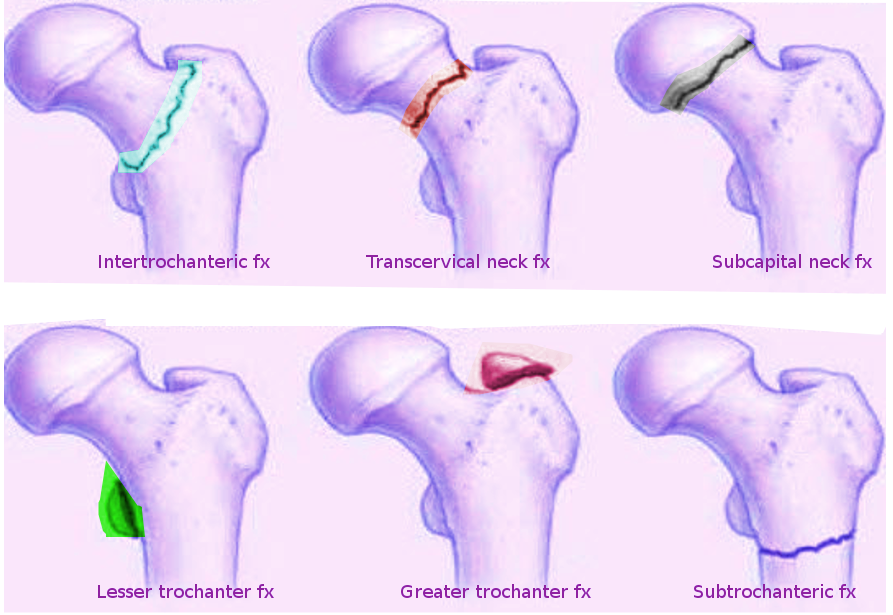

Differential Diagnosis

- Hip dislocation - displacement of the femoral head from the acetabulum

- Intertrochanteric fracture - the fracture line is more distal and lies between the greater and lesser trochanter

- Subtrochanteric fracture - the fracture line is within 5 cm distal to the lesser trochanter

- Femur fracture - the fracture line is within the femoral diaphysis

- Osteoarthritis - pain that is more chronic. Usually, patients complain of groin pain. Pain that worsens with activity or stairs

Prognosis

After femoral neck fracture, there is a 6% in-house mortality rate. There is a 1-year mortality rate between 20-30%, with the highest risk within the first six months.[2][20] Overall with hip fractures, 51% will resume independent ambulation while 22% will remain non-ambulatory.[21]

Complications

- Avascular necrosis increased risk factor with increased initial displacement and failure to obtain an anatomical reduction[13]

- Nonunion

- Dislocation increased with total hip arthroplasty surgery

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients treated with a total hip arthroplasty or hemiarthroplasty should be weight-bearing as tolerated postoperatively.[22] They should observe hip precautions depending on the surgical approach used for the procedures. Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis should be started during the perioperative period and continued for 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively. Physical therapy should begin immediately after surgery.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preoperatively, patients should be educated on the limitations on hip movements they may have due to the prosthesis. In addition, emphasis should be placed on proper activities of daily living such as sitting on the toilet, climbing stairs, and sitting and standing from a seated position after surgery.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Young patients with femoral neck fractures should be treated emergently for stabilization via open reduction internal fixation after completion of imaging and ATLS protocol as needed. With more vertically oriented fractures such a Pauwel III, a sliding hip screw is biomechanically stable.

- Elderly patients should be seen and evaluated by medical services and optimized as needed.

- Displacement and baseline activity dictate the treatment plan.

- A non-displaced fracture may have surgical treatment with screws in situ.

- A displaced fracture may undergo a total hip arthroplasty in active individuals or a hemiarthroplasty in less active individuals.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Most patients with a femoral neck fracture will present to the emergency department. Obtain the proper injury radiograph films and history from the patient. With the identification of a femoral neck injury, the patient should immediately become non-weight bearing. From a triage standpoint, the younger patients that benefit from joint sparing fixation should promptly obtain a referral to orthopedics.

For elderly patients, it is vital to identify medical comorbidities. These patients should be medically optimized before operative treatment. Especially in females, it is often painful to urinate, so the placement of a Foley catheter for comfort within the emergency department may be necessary and discontinued postoperatively with ambulation. In the orthopedic unit, it is essential to note the operative approach used because it dictates the post-operative precautions the patient should maintain. For example, for a posterior approach, the patient typically has an abduction pillow to sleep with at night. Posterior precautions also include not crossing the legs, leaning forward while seated, and letting the toes point inward. These precautions help prevent dislocation. Physical therapy and mobilization postoperatively are essential to help patients return to function.

Patients that suffer a femoral neck fracture can benefit from preoperative evaluation and postoperative management of their comorbidities. This interprofessional care team may include orthopedics, geriatrics, internal medicine, trauma surgery, anesthesia, cardiology, operating room and orthopedic nurses, physical therapists, and any other subspecialty that may help manage the patient’s comorbidities.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Crist BD, Eastman J, Lee MA, Ferguson TA, Finkemeier CG. Femoral Neck Fractures in Young Patients. Instructional course lectures. 2018 Feb 15:67():37-49 [PubMed PMID: 31411399]

Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009 Oct 14:302(14):1573-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1462. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19826027]

Shimizu T, Miyamoto K, Masuda K, Miyata Y, Hori H, Shimizu K, Maeda M. The clinical significance of impaction at the femoral neck fracture site in the elderly. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2007 Sep:127(7):515-21 [PubMed PMID: 17541613]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMiyamoto RG, Kaplan KM, Levine BR, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD. Surgical management of hip fractures: an evidence-based review of the literature. I: femoral neck fractures. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2008 Oct:16(10):596-607 [PubMed PMID: 18832603]

Brox WT, Roberts KC, Taksali S, Wright DG, Wixted JJ, Tubb CC, Patt JC, Templeton KJ, Dickman E, Adler RA, Macaulay WB, Jackman JM, Annaswamy T, Adelman AM, Hawthorne CG, Olson SA, Mendelson DA, LeBoff MS, Camacho PA, Jevsevar D, Shea KG, Bozic KJ, Shaffer W, Cummins D, Murray JN, Donnelly P, Shores P, Woznica A, Martinez Y, Boone C, Gross L, Sevarino K. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Evidence-Based Guideline on Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2015 Jul 15:97(14):1196-9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00229. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26178894]

Protzman RR, Burkhalter WE. Femoral-neck fractures in young adults. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1976 Jul:58(5):689-95 [PubMed PMID: 932067]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2006 Dec:17(12):1726-33 [PubMed PMID: 16983459]

Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC, Browner W, Cauley J, Ensrud K, Genant HK, Palermo L, Scott J, Vogt TM. Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet (London, England). 1993 Jan 9:341(8837):72-5 [PubMed PMID: 8093403]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLakstein D, Hendel D, Haimovich Y, Feldbrin Z. Changes in the pattern of fractures of the hip in patients 60 years of age and older between 2001 and 2010: A radiological review. The bone & joint journal. 2013 Sep:95-B(9):1250-4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B9.31752. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23997141]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKoval KJ, Zuckerman JD. Hip Fractures: I. Overview and Evaluation and Treatment of Femoral-Neck Fractures. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1994 May:2(3):141-149 [PubMed PMID: 10709002]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBarney J, Piuzzi NS, Akhondi H. Femoral Head Avascular Necrosis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536264]

Li M, Cole PA. Anatomical considerations in adult femoral neck fractures: how anatomy influences the treatment issues? Injury. 2015 Mar:46(3):453-8. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.11.017. Epub 2014 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 25549821]

Dedrick DK, Mackenzie JR, Burney RE. Complications of femoral neck fracture in young adults. The Journal of trauma. 1986 Oct:26(10):932-7 [PubMed PMID: 3773004]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKazley JM, Banerjee S, Abousayed MM, Rosenbaum AJ. Classifications in Brief: Garden Classification of Femoral Neck Fractures. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2018 Feb:476(2):441-445. doi: 10.1007/s11999.0000000000000066. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29389800]

Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, Tornetta P 3rd, Obremskey W, Koval KJ, Nork S, Sprague S, Schemitsch EH, Guyatt GH. Internal fixation compared with arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2003 Sep:85(9):1673-81 [PubMed PMID: 12954824]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFixation using Alternative Implants for the Treatment of Hip fractures (FAITH) Investigators., Fracture fixation in the operative management of hip fractures (FAITH): an international, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 28262269]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRogmark C, Leonardsson O. Hip arthroplasty for the treatment of displaced fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients. The bone & joint journal. 2016 Mar:98-B(3):291-7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B3.36515. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26920951]

Avery PP, Baker RP, Walton MJ, Rooker JC, Squires B, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Total hip replacement and hemiarthroplasty in mobile, independent patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck: a seven- to ten-year follow-up report of a prospective randomised controlled trial. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2011 Aug:93(8):1045-8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B8.27132. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21768626]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHedbeck CJ, Enocson A, Lapidus G, Blomfeldt R, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S, Tidermark J. Comparison of bipolar hemiarthroplasty with total hip arthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: a concise four-year follow-up of a randomized trial. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2011 Mar 2:93(5):445-50. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00474. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21368076]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEgol KA, Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD. Functional recovery following hip fracture in the elderly. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 1997 Nov:11(8):594-9 [PubMed PMID: 9415867]

Miller CW. Survival and ambulation following hip fracture. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1978 Oct:60(7):930-4 [PubMed PMID: 701341]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKoval KJ, Friend KD, Aharonoff GB, Zukerman JD. Weight bearing after hip fracture: a prospective series of 596 geriatric hip fracture patients. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 1996:10(8):526-30 [PubMed PMID: 8915913]