Introduction

The zygomatic bone (or zygoma) is a paired, irregular bone that defines the anterior and lateral portions of the face. The zygomatic complex is involved in the protection of the contents of the orbit and the contour of the face and cheeks.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The zygomatic bones are a pair of diamond-shaped, irregularly-shaped bones that protrude laterally and form the prominence of the cheeks, a portion of the lateral wall, the orbit floor, and some portions of the temporal fossa and infratemporal fossa. Usually, the zygomatic bone is a single bone bounded by sutures that articulate with the frontal, maxilla, temporal, and sphenoid bones, but it can be divided by extra sutures into two or more parts.[2] For the most part, there is an extra suture that runs perpendicularly from the facial part of the maxillozygomatic suture and dorsolaterally to the zygomatic bone, which imparts it a bipartite morphology.[2] The zygomatic bone can withstand the forces of mastication and transmitting reactionary forces from the maxilla. It also plays a crucial role in maintaining the aesthetic beauty and function of the face and protecting the eyes.[2][3] The zygomatic arch is also vital in the mastication system, as it gives rise to the masseter muscle, which is the major jaw adductor in mammals.[3] It forms from the temporal process of the zygomatic bone and the zygomatic process of the temporal bone.[4]

Embryology

In mammals, the vertebrate head evolves from neural crest cells. Neural crest cells separate from the ectoderm and migrate to other locations, such as the pharyngeal arches and facial prominences, to differentiate into various tissues.[5] The neural crest cells most likely responsible for the formation of the zygomatic bone are from the first pharyngeal arch. Bones from this embryonic facial structure later evolve into bony nasal passages and bones, such as the mandible, maxilla, malleus, Palatine, and zygomatic bones. The earliest skeleton of developing vertebrates arises from cartilage. However, as development goes on, bones begin to form by intramembranous ossification and give rise to cranial and facial bones, including the zygomatic bones.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply for the facial bones is mainly provided by the maxillary artery, which originates from a terminal branch of the external carotid artery.[6] However, a previous study by Gharb et al. demonstrated the facial artery plays a codominant role in the blood supply of facial bones, as it forms anastomoses with the maxillary artery and vascularizes the body and the maxillary, frontal, and temporal processes of the zygomatic bone.[7]

Nerves

The facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) is primarily responsible for innervating the muscles of the face. It originates from the brain stem and travels posteriorly to the abducens nerve and anteriorly to the vestibulocochlear nerve.[8] It then traverses through the temporal bone and the stylomastoid foramen where it branches off at the parotid gland. The extratemporal region of the facial nerve has five terminal branches: the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, and cervical branches.[8] The temporal branch innervates the frontalis and orbicularis oris while the zygomatic branch innervates the middle region of the face. The buccal branch provides sensation to the zygomatic and buccinator muscles while the mandibular branch innervates the lower region of the face. Finally, the cervical branch provides sensation to the muscles below the chin and the platysma muscle.[8]

The zygomatic nerve, which originates from the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve, gives off the zygomaticotemporal and zygomaticofacial branches.[9] The zygomaticotemporal branch runs along the inferolateral walls of the orbit, travels through the zygomaticofacial foramen of the zygomatic bone, and innervates the orbicularis oculi to reach the skin of the malar area.[9] It also joins with the zygomatic branches of the facial nerve and inferior palpebral branches of the maxillary nerve. The zygomaticofacial branch traverses through the lateral wall of the orbit and goes through the zygomaticofacial foramen.[10][11]

Muscles

The zygomatic bone works with the masticatory muscles to control the mastication process and aesthetic function of the face.[12] The zygomatic bones function as the origins for the masticatory muscles, especially the masseter muscles, where they help them attach inferiorly.[13] Their frontal processes are associated with the temporalis muscle in that their fibers run parallel from them and insert onto the mandibular coronoid process.[13]

Physiologic Variants

As mentioned previously, usually, the zygomatic bone is a single bone bounded by sutures, but it can be divided by extra sutures into two or more parts.[2] For the most part, there is an extra suture that runs perpendicularly from the facial portion of the maxillozygomatic suture and dorsolaterally to the zygomatic bone, which imparts it a bipartite morphology.[2] The zygomaticofacial foramen, located at the mid-lateral surface of the zygomatic bone that gives off the zygomaticofacial nerve and zygomaticofacial vessels, has also been found to vary from being double or being absent.[14] According to a study that examined 102 dry hemicrania, the zygomaticoforamen ranged from being absent to have as many as four small openings, and half of the specimens had one foramen.[14]

The zygomatic bone could also vary among different ethnic populations. According to Oettle et al., prominence of the zygomatic bone was associated with Eastern Asian populations and populations from Eastern Europe.[15] However, there was diffusion of this trait in populations across the Behring Sea and the Arctic, North America, and South America areas. Some Arctic groups show a prominence of the zygomatic bone to adapt to extreme cold conditions while groups from Australia, Malaysia, and Oceania show some prominence of the zygomatic bone.[15]

Surgical Considerations

Because the zygomatic bone may fracture during facial trauma and may involve other facial structures, such as the frontal bone, maxilla bone, temporal bone, and orbit, it is critical first to obtain a thorough, prompt ophthalmologic exam.[16] Zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures can significantly alter the structure and aesthetic beauty of the midface, including the globe, and often involve blindness or serious eye injuries. These injuries have significant associations with ocular injuries and visual sequelae than most other types of midfacial injuries. Also, researchers discovered that patients who fractured the zygomatic bone after facial trauma were seven times as likely to sustain an eye injury than those who did not experience a bony fracture after facial trauma.[16]

For the surgical management of patients with zygomatic bone fractures, several examinations are necessary. First is the assessment of gross vision as well as the presence of traumatic optic neuropathy.[16] During these tests, the presence of afferent pupillary defects or red color desaturation requires evaluation, as they may appear in patients with zygomatic bone fractures and red color perception is first to disappear in optic nerve compromise.[16] Testing of extraocular movement and visual fields is also necessary, as a constraint in extraocular muscle movement could indicate muscle entrapment. A forced duction test with an anesthetic or computed tomography scans can be performed to assess extraocular muscle entrapment.[16] Finally, sensation in the V2 distribution should undergo evaluation, as sensation in this region almost always decreases in patients with malar fractures.[16]

Clinical Significance

As mentioned previously, the zygomatic bone forms the prominence of the cheeks, a portion of the lateral wall, the orbit floor, and some parts of the temporal fossa and infratemporal fossa. The zygomatic bone is essential for enduring the forces of mastication and transmitting forces from the maxilla.[2] It also plays a vital role in maintaining the aesthetic beauty and function of the face and protecting the eyes. The zygomatic arch also gives rise to the masseter muscle, which is the major jaw adductor in mammals.[3] The zygomatic bone also connects the facial skeleton to the cranial bones by joining the maxilla to the temporal and frontal bones, which forms a portion of the lateral border of the bony orbit.[3]

The zygomatic bone may also fracture during facial trauma. Fractures of the zygomatic bone are among the most common types of facial fracture and primarily result from assaults and motor vehicle accidents.[16] These fractures are typically complex, as the zygomatic bone articulates with four other bones, and these fractures rarely occur in isolation. The masseter muscles are also the major muscle providing the most significant deforming force on the zygomatic bones.[16] Additionally, because the zygomatic bone forms a substantial portion of the orbital wall and floor, zygomatic bone fractures often involve displacement of the orbit. Therefore, a thorough ophthalmologic exam should be conducted for patients with zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures to assess the severity of facial trauma.[16]

Although rare, fibrous dysplasia of the zygomatic bone may occur. The disease often manifests as a continuously growing mass in late childhood.[17] Even though it frequently involves the maxilla and the mandible, some rare cases may include the zygomatic bone. Fibrous dysplasia of the zygomatic may result in many symptoms, such as orbital dysplasia, diplopia, and proptosis.[17]

Media

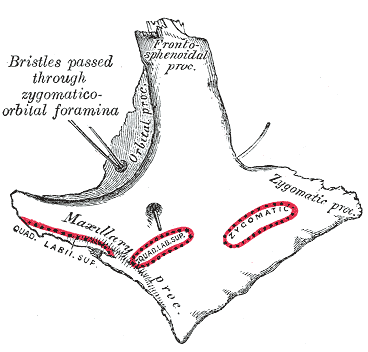

(Click Image to Enlarge)

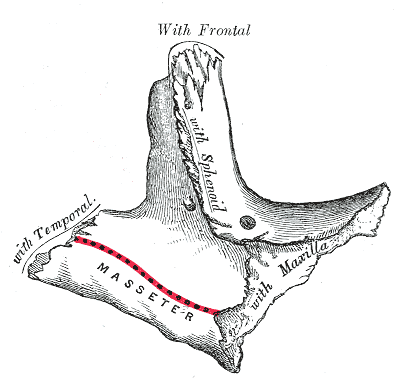

(Click Image to Enlarge)

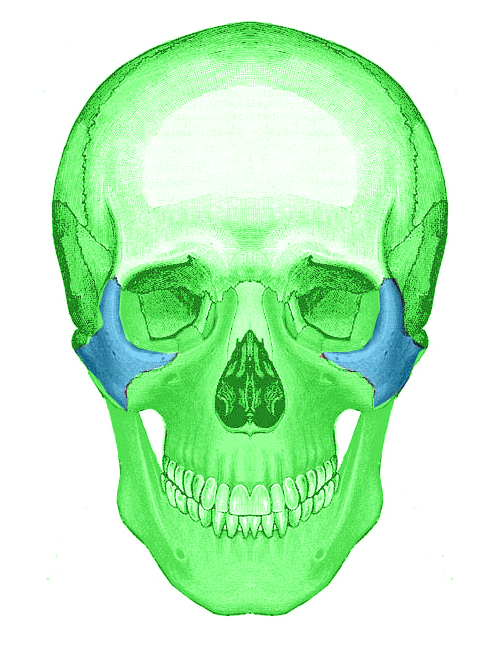

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ungari C, Filiaci F, Riccardi E, Rinna C, Iannetti G. Etiology and incidence of zygomatic fracture: a retrospective study related to a series of 642 patients. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2012 Oct:16(11):1559-62 [PubMed PMID: 23111970]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWang Q, Dechow PC. Divided Zygomatic Bone in Primates With Implications of Skull Morphology and Biomechanics. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2016 Dec:299(12):1801-1829. doi: 10.1002/ar.23448. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27870346]

Malaviya P, Choudhary S. Zygomaticomaxillary buttress and its dilemma. Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2018 Aug:44(4):151-158. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2018.44.4.151. Epub 2018 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 30181981]

Smith AL, Grosse IR. The Biomechanics of Zygomatic Arch Shape. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2016 Dec:299(12):1734-1752. doi: 10.1002/ar.23484. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27870343]

Heuzé Y, Kawasaki K, Schwarz T, Schoenebeck JJ, Richtsmeier JT. Developmental and Evolutionary Significance of the Zygomatic Bone. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2016 Dec:299(12):1616-1630. doi: 10.1002/ar.23449. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27870340]

Otake I, Kageyama I, Mataga I. Clinical anatomy of the maxillary artery. Okajimas folia anatomica Japonica. 2011 Feb:87(4):155-64 [PubMed PMID: 21516980]

Gharb BB, Rampazzo A, Kutz JE, Bright L, Doumit G, Harter TB. Vascularization of the facial bones by the facial artery: implications for full face allotransplantation. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2014 May:133(5):1153-1165. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000111. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24445880]

Dulak D, Naqvi IA. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 7 (Facial). StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252375]

Iwanaga J, Wilson C, Watanabe K, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS. Anatomical Study of the Zygomaticotemporal Branch Inside the Orbit. Cureus. 2017 Sep 29:9(9):e1727. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1727. Epub 2017 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 29201576]

Khalid S, Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. Bilateral Absence of the Zygomatic Nerve and Zygomaticofacial Nerve and Foramina. Cureus. 2017 Jul 23:9(7):e1505. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1505. Epub 2017 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 28948125]

Iwanaga J, Badaloni F, Watanabe K, Yamaki KI, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS. Anatomical Study of the Zygomaticofacial Foramen and Its Related Canal. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Jul:29(5):1363-1365. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004457. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29521755]

Dechow PC, Wang Q. Development, Structure, and Function of the Zygomatic Bones: What is New and Why Do We Care? Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2016 Dec:299(12):1611-1615. doi: 10.1002/ar.23480. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27870341]

Márquez S, Pagano AS, Schwartz JH, Curtis A, Delman BN, Lawson W, Laitman JT. Toward Understanding the Mammalian Zygoma: Insights From Comparative Anatomy, Growth and Development, and Morphometric Analysis. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2017 Jan:300(1):76-151. doi: 10.1002/ar.23485. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28000398]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMartins C, Li X, Rhoton AL Jr. Role of the zygomaticofacial foramen in the orbitozygomatic craniotomy: anatomic report. Neurosurgery. 2003 Jul:53(1):168-72; discussion 172-3 [PubMed PMID: 12823886]

Oettlé AC, Demeter FP, L'abbé EN. Ancestral Variations in the Shape and Size of the Zygoma. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2017 Jan:300(1):196-208. doi: 10.1002/ar.23469. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28000408]

Lee EI, Mohan K, Koshy JC, Hollier LH Jr. Optimizing the surgical management of zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2010 Nov:24(4):389-97. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1269768. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22550463]

Demirdöver C, Sahin B, Ozkan HS, Durmuş EU, Oztan HY. Isolated fibrous dysplasia of the zygomatic bone. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2010 Sep:21(5):1583-4. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181edc5af. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20818245]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence