Benign Familial Pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey Disease)

Benign Familial Pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey Disease)

Introduction

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD; OMIM 169600), also known as benign familial pemphigus, is a rare genodermatoses firstly described in 1939 by the Hailey brothers.[1] HHD is characterized by impaired keratinocyte adhesion resulting in widespread intraepidermal acantholysis.

Clinically, lesions appear as vesicles and bullae forming upon rupture, painful erosions, and rhagades in flexural areas. HHD is a chronic disease with a relapsing-remitting clinical course. Exacerbations are mainly triggered by sweating, minor trauma, and secondary infections. No curative treatment is available. Patient management can be challenging. Mild cases can be controlled successfully with intermittent courses of topical corticosteroids and antibiotics.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Hailey-Hailey disease is an autosomal dominant genodermatoses with complete penetrance and variable expressivity amongst affected family members. There is no positive family history in approximately 15 to 30% of cases. These cases are due to either sporadic genetic mutations or undiagnosed mild diseases of other family members.[2] Mutations in the ATP2C1 gene (ATP2C1; OMIM 604384), localized at 3q21-q24, encode the human secretory-pathway Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPase isoform 1 (hSPCA1) of the Golgi apparatus is responsible for HHD.[3][4]

More than 214 mutations have been identified scattered along the ATP2C1 gene without any hotspot or clustering.[5] The majority are loss-of-function mutations.[6][7] The hSPCA1 pump supplies the Golgi lumen with Ca2+ and Mn2+ and helps to maintain normal Ca2+/Mn2+ intracellular concentrations. In keratinocytes cultured from lesional and non-lesional skin of HHD patients, the regulation of cytosolic Ca2+ was found deficient, resulting in increased intracellular levels of Ca2+ and decreased levels of Ca2+ within Golgi bodies.[4]

HHD is characterized by extensive interfamilial and intrafamilial phenotypic variability, suggesting that environmental factors and genetic modifiers may affect the clinical expression of this disease.[6] A direct correlation of genotype/phenotype (age of onset, severity, progression) has not been possible yet. However, some specific mutations correlate with a genitoperineal involvement or milder phenotypes.[8][9]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of HHD is unknown, but it is estimated to be similar to that of Darier disease, and thus, it is calculated at around 1/50.000.[10] The female-to-male ratio is equal to one. There is no apparent predilection for any ethnic group.

The onset of the disease occurs in the late teenage years or the third and fourth decades of life. A case of a 5-year-old infant with diffuse lesions carrying an ATP2C1 mutation has been reported.[11] In almost 50% of cases, lesions appear initially in the neck area, followed by the inguinal and axillary folds.[2]

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism of acantholysis in benign familial pemphigus (Hailey Hailey disease) is complex and remains uncertain. The identification of mutations in the ATP2C1 gene suggested a role of a Ca2+-dependent signaling pathway in regulating cell-to-cell adhesion and epidermal differentiation. Desmosomes, tight and adherens junctions are responsible for keratinocyte adhesion in the epidermis.

Cadherins, significant components of desmosomes and adherens junctions, are well-studied transmembrane glycoproteins that promote cell-cell adhesion in a Ca2+-dependent manner. In HHD keratinocytes, increased cytosolic Ca2+ could impair post-translational modifications (proteolytic processing, glycosylation, trafficking, or sorting) of cadherins and other structural proteins.[10]

Leinonen et al. identified a lower Ca2+ content in the basal epidermal layers of lesional skin of HHD patients compared to nonlesional and normal control skin.[12] The disturbed Ca2+ gradient was linked to abnormal tissue distribution and diminished functionality of ATP receptors. These alterations promoted a defect in the keratinocyte differentiation process.[12]

Furthermore, adherens junctions couple intercellular adhesion to the actin cytoskeleton. Impaired actin reorganization was identified in HHD and correlated with a marked decrease in cellular ATP, in vitro and in vivo, reflecting insufficient cellular ATP stores.[13] This defective ATP production could be related to a mitochondrial calcium overload.[14] A recent study analyzing proteomic changes in skin lesions of HHD revealed dysregulation of extracellular matrix and cell cytoskeleton components.[15]

Finally, two studies highlighted the role of complex multi-pathway alterations and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of HHD.[16][17] Notch1 and p63 are part of a regulatory signaling controlling keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation. HHD-derived keratinocytes undergo oxidative stress and subsequently exhibit downregulation of both Notch1 and Itch expression and differential regulation of different p63 isoforms.[16]

Oxidative stress-mediated induction of miR-125b expression, a specific microRNA that modulates gene expression post-transcriptionally, may be responsible for the suppression of Notch1 and p63 expression in HHD.[17]

ATP2C1 is ubiquitously expressed in human tissues, but HHD manifestations are limited to the intertriginous skin areas. A possible explanation is that epidermal keratinocytes express highly ATP2C1 and are less capable of compensating for the inactivation of hSPCA1 compared to other tissues.[18][19]

Histopathology

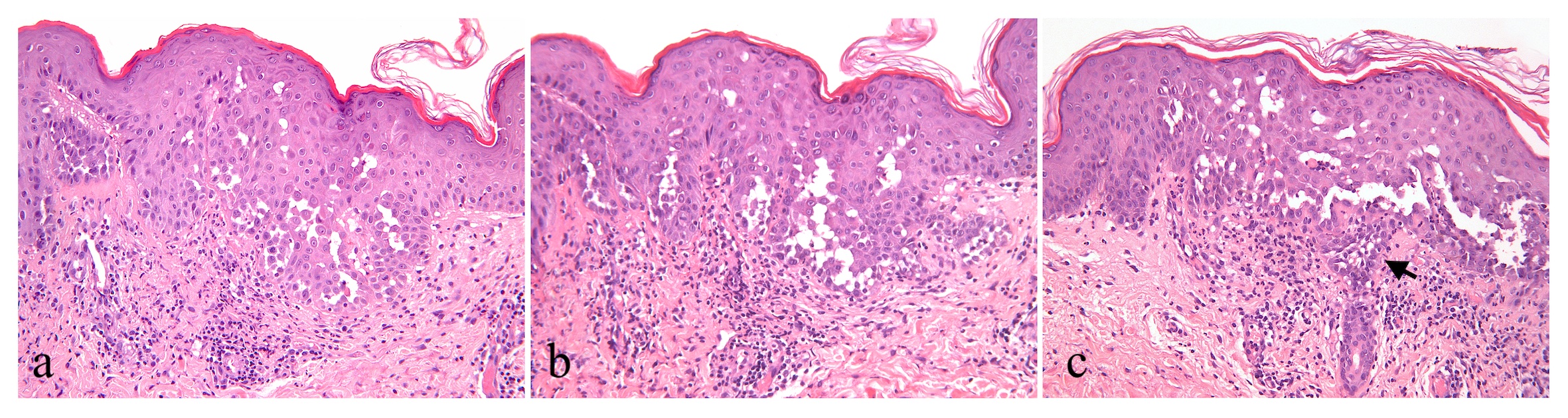

Histologically, Hailey-Hailey disease shows widespread keratinocyte acantholysis appearing as a "dilapidated brick wall" with suprabasal clefting (lacunae). Dyskeratosis, when present, is mild, but dyskeratotic keratinocytes have a well-defined nucleus and preserved cytoplasm. Elongated dermal papillae "villi" extend into the lacunae, lined with a single layer of basal cells.

Suprabasal clefting in HHD spares the adnexal structures. The superficial dermis can contain focal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Chronic lesions present epidermal hyperplasia with ortho- and parakeratosis. The parakeratotic crust sometimes contains neutrophils and bacteria.

Direct immunofluorescence is negative and helps differentiate from pemphigus vulgaris.

History and Physical

The typical skin lesions of Hailey-Hailey disease usually occur in friction or intertriginous areas, including the sides and back of the neck, axillary, inguinal, and perineal folds (scrotum, vulva). The sub-mammary area affects as much as 50% of female patients with HHD. Isolated vulvar disease is possible.

Primary lesions are grouped, flaccid vesicles and blisters on an erythematous base or normal skin. A foul-smelling exudate is produced upon rupture, and crusted erosions are formed. Lesions develop peripherally in a serpiginous pattern with an active vesico-pustular border. When central resolution occurs, expanding lesions can obtain a circinate form. Chronic lesions, especially in the intertriginous areas, tend to form erythematous plaques with worm-eaten erosions and painful "rhagades" or moist vegetations.[2]

Lesions present a symmetrical, bilateral distribution. Dissemination is rare and often secondary to a staphylococcal, viral, or yeast infection.[20]

Approximately 70% of HHD patients have longitudinal white bands in their fingernails (longitudinal leukonychia).[21] Oral, esophageal, vaginal, and conjunctival involvements have been reported but remain uncommon.[22][23][24] There are no other known extracutaneous manifestations of HHD.

Two distinct segmental HHD patterns have been described, reflecting mosaicism. These patients show a band-like distribution of lesions following the Blaschko lines. Type 1 HHD patients present a segmental distribution of lesions with no family history. It is due to a de novo post-zygotic mutation occurring at the first stages of embryogenesis.[25]

These patients risk transmitting non-segmental HHD to their children if the mutation affects the germline (gonadal mosaicism), and preconception genetic counseling is advised. In type 2 segmental HHD, severely affected segmental lesions and "classical" non-segmental HHD lesions are superimposed. The deeper portions of the adnexal structures express the genetic defect in the affected segment. Type 2 segmental HHD is due to a germinal mutation with associated loss of heterozygosity.[26] Affected family members have non-segmental HHD, and the risk of transmission from the affected parent to the offspring is 50%.[27]

Acute exacerbations of the disease are often triggered by minor trauma, friction, heating, humidity irradiation, and secondary infections. These disease-modifying factors can be responsible for the induction of acantholysis and skin lesions even in non-flexural sites within 24 hours of exposure. Staphylococcal infections, in particular, may aggravate acantholysis by producing exfoliative toxins leading to severe flares. An infection should be suspected when lesions are malodorous or vegetating, and topical or/and oral anti-infective agents should be prescribed.

HDD can severely impact the quality of life of patients. More precisely, patients describe severe debilitating symptoms such as itch, pain, burning sensation, and body malodor. HDD is associated with crucial psychological distress and significantly impacts social functioning.[28]

The mean Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is comparable to other severe dermatoses such as psoriasis.[29] There can be a lack of correlation between the physicians' assessment of disease severity and the degree of handicap experienced by the patient, as in other chronic dermatoses leading to undertreatment in some cases.[30]

Evaluation

Diagnosis of Hailey-Hailey disease can be made clinically, with a follow-up confirmation using skin histopathology.

Dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy may also contribute to an early diagnosis of HHD. HHD's most common dermoscopic features include polymorphous vessels such as glomerular and linear-looped vessels within a pink-whitish background. In reflectance confocal microscopy, suprabasal partial acantholysis and clefting are the main findings associated with crusts, dilated papillae with tortuous vessels, and inflammatory cells.[31] Adnexal sparing is also observed.

A search of mutations in the ATP2C1 gene by molecular biology is not routinely performed but can be helpful in difficult-to-diagnose cases.

Treatment / Management

HHD is a chronic disease with no curative treatment. Current therapeutic strategies aim to control disease flares, improve patients’ quality of life, and provide prolonged remissions. The management of HHD is based on anecdotal data from the off-label use of various topical, systemic and interventional treatments. Since HHD is a relapsing-remitting disease and lesions can present spontaneous remission, data from individual case reports and small case series with no control group are of limited value (Level of evidence 5). Randomized, prospective studies are lacking.

General Measures

Avoiding triggering factors such as mechanical stress, heat, sun exposure, and sweating are essential measures to prevent disease exacerbations. Overall, lifestyle modifications are necessary, and patients’ education can be helpful. Patients are advised to lose weight and wear loose clothing and underwear to avoid friction in the intertriginous areas. Physical activity involving friction should be limited. Adhesive and occlusive dressings should be avoided.

Personal hygiene and mild daily cleansing with non-soap-based surfactants and synthetic detergents are recommended. Applications of antiseptics are essential (octenidine, chlorhexidine).[32] Bathing in dilute bleach (1/2 cup of 5% bleach in a full bathtub for a final concentration of 0.005%) for 10 minutes twice weekly can be proposed by analogy with atopic dermatitis.[33] Antiseptic treatments can decrease bacterial colonization without the risk of bacterial resistance induction.(A1)

Topical Treatments

Topical treatments are the mainstay of HHD management. Antiseptics and topical anti-inflammatory treatments applied during disease flares are often enough to control mild cases of HHD.[32]

Zinc Paste

Zinc oxide paste protects the skin against friction and humidity by forming a barrier. Zinc oxide paste 50% applied twice daily alone was found to be more effective than topical tacrolimus.[34] Zinc oxide can prevent the colonization of skin lesions and has been reported to increase in vitro levels of intracellular calcium.[35](B3)

Topical Corticosteroids

Moderate to high-intensity topical steroids are often proposed during disease outbreaks as a first-line treatment, with continuous daily applications until clinical remission is obtained.[32][36] Prolonged treatment courses are limited by the risk of steroid-induced atrophy and striae, especially in flexural areas.(B3)

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors (Tacrolimus, Pimecrolimus)

Applying topical calcineurin inhibitors twice a day to affected areas is an excellent way to control HHD. It can be proposed as a second-line or long-term maintenance treatment to avoid steroid-induced skin atrophy.[37][38][39] Lesion resolution typically occurs after two weeks.[40][41] Tacrolimus 0.1% is available as an ointment, and pimecrolimus 1% as a cream. (B3)

Alternative topical agents anecdotally include calcitriol, 5-fluorouracil, and cadexomer iodine.[42][43][44](B3)

Antibiotics

Colonization and infection with Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, dermatophytes, herpes simplex virus, and Candida species may exacerbate lesions. The use of topical or oral antimicrobial agents depends on the extent of skin lesions. Bacterial and fungal cultures should guide treatment. Long-term use of topical and oral antibiotics can induce acquired resistance.

In a case series of 58 patients, 43% improved with oral erythromycin or penicillin antibiotics. Doxycycline and minocycline belong to the class of tetracyclines. Doxycycline at a dose of 100 mg daily for up to 3 months has been associated with good clinical outcomes in a case series of 6 patients with HHD and 2 case reports.[45][46][47] (B3)

In patients experiencing recurrence, doxycycline could be used as maintenance at half-dose. Minocycline at 100 mg twice daily for two weeks and a maintenance dose of 100 mg daily for two months has been associated with complete clearance in one patient.[48] Besides their antibiotic potential, tetracyclines exert anti-inflammatory properties mediated by the inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis, the regulation of inflammatory cytokines production by keratinocytes, and the inhibition of matrix metalloproteases.[49]

The most common side effects are gastrointestinal intolerance (esophagitis) and photosensitivity. The minocycline-related risk of skin hyperpigmentation and hypersensitivity reactions such as DRESS syndrome should limit its use in this indication. Dapsone has been used anecdotally in HHD as well.[50]

Almost 20% of mutations in HHD are base substitutions resulting in a premature stop codon. They are responsible for synthesizing a truncated form of hSPCA1[10]. In several case reports, topical gentamicin 0.1% has successfully been used for treating HHD.[51][52][51] (B3)

In a patient with HHD carrying a stop mutation, topical gentamicin 0.1% applied for 7-10 days was more effective than topical 5% boric acid despite their similar antimicrobial spectrum of action.[51] In a Saccharomyces cerevisiae model of HHD, the authors further showed that topical paromomycin, another aminoglycoside, can induce read-through of a premature nonsense mutation of ATP2C1.[51](B3)

Systemic Therapies

Even though acantholysis is the primary event in HHD, the main target of available systemic treatments is cutaneous inflammation. The development of skin lesions in HHD requires a reduction in the ATP2C1 gene expression from the intact allele and a heterozygous mutation of the ATP2C1 gene.[53]

The pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 could play an essential role in regulating ATP2C1 expression. Thus, corticosteroids, cyclosporine A and tacrolimus could be effective in HHD due to their ability to regulate IL-6 and IL-8 levels and indirectly ATP2C1 expression. Additionally, retinoids and oral corticosteroids can act by directly reversing UVB-induced ATP2C1 mRNA suppression.[53]

Oral corticosteroids such as prednisolone at daily doses of 0.5 mg/kg can control severe flares in selected cases. Still, rebounds can be expected at the end of treatment.[54] Oral corticosteroids are not suitable for long-term therapy.

Several case reports have been published on the use of oral retinoids in HHD (acitretin, isotretinoin, alitretinoin, etretinate). The more robust evidence is available for acitretin at a dose of 10 to 25 mg daily, but the clinical efficacy is not constant.[55][56][57][58] At higher doses, acitretin can exacerbate acantholysis.[32] For females of childbearing age, isotretinoin should be preferred. A synergistic effect of 25 mg acitretin and narrowband ultraviolet B (nbUVB) phototherapy has also been reported.[58](B3)

Other immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine have been tested with varying efficacy results but are of limited value in clinical practice.[59][60] Further studies are needed to validate their use for recalcitrant and extended cases.(B3)

Interventional Treatments

Surgery

In highly invalidating, localized lesions, resisting medical treatment, full-thickness excision, followed by secondary intention healing, primary closure, or split-skin grafting, has been proposed.[61] For some authors, primary closure presents an increased risk of recurrence and morbidity and should not be preferred.[62] Currently, ablative techniques have progressively replaced surgical excision with the advantages of shorter downtime and lower complication rates.

Ablative Techniques

Destruction of the epidermis until the level of the papillary dermis is an interesting treatment option for HHD. The adnexal structures do not bear the defect, allowing tissue reepithelization.[63] Different ablative techniques are used to treat HHD, including laser (CO2, erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet [Er: YAG], diode laser), electrodesiccation, mechanical dermabrasion, and photodynamic therapy.[64] (B3)

Ablative techniques are preferred in cases of recalcitrant, localized disease. It is noteworthy that the severe involvement of deep adnexal structures in type 2 segmental HHD makes these patients bad candidates for ablative treatments.[65](B3)

Mechanical dermabrasion was initially proposed as an alternative to surgical excision.[63][66][67] In a retrospective series of 10 patients treated successfully with dermabrasion, the recurrence rate by treated area was only 17% after a median follow-up of 42 months. Relapsing patients were treated with another session with no subsequent relapse.[66] Mechanical dermabrasion is nevertheless less and less used nowadays as it is more hemorrhagic than laser treatments.(B3)

Among laser treatments, CO2 laser is better evaluated. In most studies, CO2 laser has been used in continuous, defocused mode with power settings ranging from 5 to 25 W and 1 to 5 passes.[68][69][70] In a retrospective series of 13 patients with patient-reported outcomes, CO2 laser allowed a substantial improvement in the quality of life in 69% of cases. The mean time to heal was 6.3 weeks.[68] (A1)

No recurrence was noted within the treated area. Post-inflammatory hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation occurred in almost 85% of cases and scarring in 30%. In another series of 8 patients, four achieved more than 75% clinical improvement and two 50 to 75%.[68] Recurrences at the border of previously treated areas are well described after ablative treatments and respond to additional laser sessions.(B2)

Pulse dye laser at 595-nm has been evaluated in a series of 7 patients using subpurpuric settings (pulse duration of 6 to 10 msec, spot size 7 to 10 mm, fluence 7-10 J/cm). Six patients achieved mild-to-complete clearance after an average of 5 sessions.[71] The lesions resolution time ranged from 2 weeks to 2 months. Four patients relapsed prematurely at the end of treatment.(B3)

Er: YAG and Alexandrite laser efficacy has been evaluated in isolated case reports with variable outcomes.[70] In the only reported case of HHD treated with diode laser at 1450 nm, a reduction in malodor and sweating was noted without clinical improvement of lesions.[72](A1)

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

In a case series of 8 patients with long-lasting, recalcitrant HHD lesions, PDT with methyl-amino levulinate achieved complete or partial response for all treated lesions and no recurrence after a follow-up of 3 to 36 months.[73] A standard protocol of 3 sessions with 3-week intervals was used. In another recent retrospective study, ten patients with difficult-to-treat HHD received PDT with 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA).[74]

All patients achieved complete remission after 1 to 12 weekly sessions. Three patients experienced a relapse that responded well to further sessions. Tolerability was excellent since 5-ALA is a second-generation photosensitizer that penetrates deeper into the skin, beyond the nerve endings, and is associated with reduced perioperative pain. The exact molecular mechanism behind the efficacy of PDT in HHD remains elusive but is probably related to its intrinsic photooxidative properties. PDT could act by the induction of tissue repair mechanisms and the subsequent improvement of the mechanical integrity of the epithelium.[75]

Botulinum Toxin Injection

Sweating is a well-identified factor of HHD exacerbations. Reducing the production of eccrine sweat glands by blocking the release of acetylcholine from the sympathetic nerve fibers with botulinum toxin appears to be a promising treatment for HHD.[76] (B3)

In a prospective, single-center, interventional study, 26 patients with HHD were injected with botulinum toxin type A (BtxA) at a dose of 50 IU per 100 cm(2.5 IU/0.1 ml every 2 cm). BtxA was effective with an 85% reduction of the treated area at six months. However, the cost of this intervention has to be taken into consideration. BtxA can be proposed as a first-line approach for mild-to-moderate axillary and inguinal lesions of HHD.[76][60](B3)

Narrowband Ultraviolet B Phototherapy

The effect of ultraviolet light exposure differs between patients. Some patients can present flares even in unaffected skin after sun exposure, while others experience clinical improvement. In vitro, UVB light induces the suppression of ATP2C1 mRNA but is an insufficient cellular stress factor alone for the induction of HHD lesions.[53][77] Several case reports have suggested the efficacy of nbUVB therapy either in monotherapy or synergistically with retinoids in HHD.[78] In selected patients, NbUVB phototherapy could be an interesting treatment option for HHD.(B3)

The use of other interventional treatments such as radiofrequency and electron beam radiotherapy (cumulative dose of 20 Gy in 10 fractions) has been reported in isolated cases.[79][80](B3)

Novel Therapies

Emerging therapies for HHD include oral anticholinergic drugs (oxybutynin, glycopyrrolate), afamelanotide, oral magnesium chloride, oral naltrexone, apremilast, and dupilumab.

Glycopyrrolate and other anticholinergics such as oxybutynin are thought to work in HHD by controlling sweating. Glycopyrrolate is an anticholinergic agent that is safe and effective in hyperhidrosis with the advantage of fewer central nervous system adverse events since it does not cross the blood-brain barrier. Two case reports noted the efficacy of low-dose oral and topical glycopyrrolate, respectively, in HHD.[81][82](B3)

Naltrexone is an orally active opioid antagonist that blocks µ- and δ-opioid receptors. At doses ranging from 50 to 100 mg daily, naltrexone is approved to treat opioid addiction. At low doses, naltrexone seems to influence various systemic pathways with paradoxical analgesic and systemic anti-inflammatory effects.[83] In 2017, two small case series reported the efficacy of low-dose naltrexone in HHD for the first time. All six patients reached complete to almost complete clearance after 1 to 3 months of treatment with doses varying from 3 to 4.5 mg per day. Treatment was well tolerated.[83][84]

Apremilast at a dose of 30 mg twice daily has been used off-label in HHD in several case reports with good results.[85] On the other hand, Riquelme-Mc Loughlin et al. reported a lack of response or premature treatment cessation due to intolerance in 5 consecutive cases of resistant HHD.[86] A combined treatment of apremilast and dermabrasion or botulinum toxin has also been reported.[87][88](B3)

Two small case series of 5 patients report the efficacy of dupilumab, a fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that inhibits the signaling of IL-4 and IL-13 in HHD but again, large-scale, long-term data are lacking.[89][90](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of Hailey-Hailey disease includes:

- Darier disease

- Grover disease

- Pemphigus vulgaris/vegetans

- Psoriasis inversa

- Tinea cruris

- Intertriginous candidiasis

- Erythrasma

- Galli-Galli disease

Prognosis

Hailey-Hailey disease has a chronic fluctuating course. Patients with HHD can undergo recurrent flares and remissions lasting months to years. In some cases, the severity of HHD tends to improve with age, but lack of improvement or deterioration is also possible.[2]

Complications

Secondary infections are quite common, especially on erosive and macerated plaques of Hailey-Hailey disease, and can trigger the exacerbation or even acute dissemination of lesions.[20] Bacterial (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes), fungal (Candida species), and viral (herpes simplex, poxvirus, human papillomavirus) infections require prompt initiation of antimicrobial treatment for disease control. Staphylococci and other microbes may induce IL-6 and IL-8 production in keratinocytes, decreasing hSPCA1 expression in an autocrine fashion.[91][53]

Chronic inflammation of long-lasting, recalcitrant lesions of HHD can lead to malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma.[92] This transformation has been mainly described in the literature for genital lesions and was associated, in some cases, with a human papillomavirus infection.[93]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Avoiding triggering factors is of paramount importance in preventing exacerbations of Hailey-Hailey disease. Overall, patients’ education on precipitating factors can help them to apply the necessary lifestyle modifications. Preventative measures include proper hygiene practices such as daily cleaning with a gentle cleanser and an antiseptic solution to limit secondary infections and avoidance of sun exposure. Flares are common during summer due to heat and humidity. Patients should also avoid any physical activity involving friction and tight-fitting clothing. In patients with obesity, weight loss can help to reduce friction in flexural areas and is highly recommended.

Non-segmental and type 2 segmental HHD are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Patients with type 1 segmental HHD have a risk of transmitting non-segmental HHD to their children in case of gonadal mosaicism. Thus, patients with HHD should be offered genetic counseling.

Pearls and Other Issues

- HHD is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatoses with complete penetrance and variable expressivity.

- HHD is a chronic disease with a remitting-relapsing course.

- Mutations in the ATP2C1 gene, localized at 3q21-q24 that encodes the human secretory-pathway Ca/Mn-ATPase isoform 1 of the Golgi apparatus, are responsible for HHD.

- The typical skin lesions usually occur in friction or intertriginous areas.

- Clinically, ruptured vesicles and blisters tend to form erythematous plaques with worm-eaten erosions and painful "rhagades."

- Acantholysis throughout the spinous layer, appearing as a "dilapidated brick wall'' is a hallmark of HHD histology.

- Avoiding triggering factors such as mechanical stress, heat, sun exposure, and sweating are essential measures to prevent disease flares.

- There is no curative treatment for Hailey-Hailey disease. Antiseptics and intermittent topical anti-inflammatory therapies can help control mild cases of HHD.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hailey-Hailey disease follows a chronic course with lesions tending to wax and wane. In chronic, poorly controlled lesions, there is a risk of malignant transformation, especially in the vulvar area. Thus, a regular follow-up with a dermatologist is essential. Considering the burdensome symptoms of HHD and the complexity of clinical management, an integrated interprofessional approach coordinated by a dermatologist and specialty-trained dermatology nurses is recommended. [Level 5]

An interprofessional team dedicated to HHD management should include a specialist in genetic counseling, a psychologist and mental health specialists, a dietician, and a pharmacist. Genetic counseling upon diagnosis and pre-conceptually should be proposed. A psychologist and a mental health consult may be necessary in case of disease-related anxiety and depression.

Patient education regarding photoprotection, proper hygiene practices, and adequate lifestyle modifications by specialty-trained dermatology nurses are essential. Furthermore, patients should learn with the help of dedicated patient education consults to recognize early signs of disease flares and secondary infections for prompt initiation of adequate treatment. The role of the primary care provider in long-term patient activation and engagement in self-management is central.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Suprabasal acantholysis with acantholytic cells characteristically throughout most of thickness of the hyperplastic epidermis giving the appearance of a dilapidated brick wall (a,b,c). Small suprabasal separations -lacunae and vesicles are formed. Elongated papillae lined by a single layer of basal cells protrude upward into the bulla (b,c). In the superficial dermis, moderately dense perivascular mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate and telangiectatic capillaries. Only focal and limited involvement of adnexa - eccrine sweat gland by acantholysis (arrow) (c). [H/E stain X 200 magnification] Contributed from Dermatology Department, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece

References

HAILEY H. Familial benign chronic pemphigus; report thirteen years after first observation of a new entity. Southern medical journal. 1953 Aug:46(8):763-5 [PubMed PMID: 13076803]

Burge SM. Hailey-Hailey disease: the clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis. The British journal of dermatology. 1992 Mar:126(3):275-82 [PubMed PMID: 1554604]

Sudbrak R, Brown J, Dobson-Stone C, Carter S, Ramser J, White J, Healy E, Dissanayake M, Larrègue M, Perrussel M, Lehrach H, Munro CS, Strachan T, Burge S, Hovnanian A, Monaco AP. Hailey-Hailey disease is caused by mutations in ATP2C1 encoding a novel Ca(2+) pump. Human molecular genetics. 2000 Apr 12:9(7):1131-40 [PubMed PMID: 10767338]

Hu Z, Bonifas JM, Beech J, Bench G, Shigihara T, Ogawa H, Ikeda S, Mauro T, Epstein EH Jr. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nature genetics. 2000 Jan:24(1):61-5 [PubMed PMID: 10615129]

Xiao Z, Liu ZG, Ou Yang XL, Yu SM, Zeng JR, Li CM. Two Novel Variants and One Previously Reported Variant in the ATP2C1 Gene in Chinese Hailey-Hailey Disease Patients. Molecular syndromology. 2021 Jun:12(3):148-153. doi: 10.1159/000514282. Epub 2021 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 34177430]

Dobson-Stone C, Fairclough R, Dunne E, Brown J, Dissanayake M, Munro CS, Strachan T, Burge S, Sudbrak R, Monaco AP, Hovnanian A. Hailey-Hailey disease: molecular and clinical characterization of novel mutations in the ATP2C1 gene. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2002 Feb:118(2):338-43 [PubMed PMID: 11841554]

Wang Z, Li L, Sun L, Mi Z, Fu F, Yu G, Fu X, Liu H, Zhang F. Review of 52 cases with Hailey-Hailey disease identified 25 novel mutations in Chinese Han population. The Journal of dermatology. 2019 Nov:46(11):1024-1026. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15055. Epub 2019 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 31435946]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePernet C, Bessis D, Savignac M, Tron E, Guillot B, Hovnanian A. Genitoperineal papular acantholytic dyskeratosis is allelic to Hailey-Hailey disease. The British journal of dermatology. 2012 Jul:167(1):210-2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10810.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22229453]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMatsuda M, Hamada T, Numata S, Teye K, Okazawa H, Imafuku S, Ohata C, Furumura M, Hashimoto T. Mutation-dependent effects on mRNA and protein expressions in cultured keratinocytes of Hailey-Hailey disease. Experimental dermatology. 2014 Jul:23(7):514-6. doi: 10.1111/exd.12410. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24698124]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFoggia L, Hovnanian A. Calcium pump disorders of the skin. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2004 Nov 15:131C(1):20-31 [PubMed PMID: 15468148]

Xu Z, Zhang L, Xiao Y, Li L, Lin Z, Yang Y, Ma L. A case of Hailey-Hailey disease in an infant with a new ATP2C1 gene mutation. Pediatric dermatology. 2011 Mar-Apr:28(2):165-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01088.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20403116]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeinonen PT, Hägg PM, Peltonen S, Jouhilahti EM, Melkko J, Korkiamäki T, Oikarinen A, Peltonen J. Reevaluation of the normal epidermal calcium gradient, and analysis of calcium levels and ATP receptors in Hailey-Hailey and Darier epidermis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2009 Jun:129(6):1379-87. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.381. Epub 2008 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 19052563]

Aronchik I, Behne MJ, Leypoldt L, Crumrine D, Epstein E, Ikeda S, Mizoguchi M, Bench G, Pozzan T, Mauro T. Actin reorganization is abnormal and cellular ATP is decreased in Hailey-Hailey keratinocytes. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2003 Oct:121(4):681-7 [PubMed PMID: 14632182]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJahangir A, Ozcan C, Holmuhamedov EL, Terzic A. Increased calcium vulnerability of senescent cardiac mitochondria: protective role for a mitochondrial potassium channel opener. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2001 Jul 31:122(10):1073-86 [PubMed PMID: 11389925]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhang D, Huo J, Li R, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Li X. Altered levels of focal adhesion and extracellular matrix-receptor interacting proteins were identified in Hailey-Hailey disease by quantitative iTRAQ proteome analysis. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2019 Mar:120(3):3801-3812. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27662. Epub 2018 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 30506709]

Cialfi S, Oliviero C, Ceccarelli S, Marchese C, Barbieri L, Biolcati G, Uccelletti D, Palleschi C, Barboni L, De Bernardo C, Grammatico P, Magrelli A, Salvatore M, Taruscio D, Frati L, Gulino A, Screpanti I, Talora C. Complex multipathways alterations and oxidative stress are associated with Hailey-Hailey disease. The British journal of dermatology. 2010 Mar:162(3):518-26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09500.x. Epub 2009 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 19903178]

Manca S, Magrelli A, Cialfi S, Lefort K, Ambra R, Alimandi M, Biolcati G, Uccelletti D, Palleschi C, Screpanti I, Candi E, Melino G, Salvatore M, Taruscio D, Talora C. Oxidative stress activation of miR-125b is part of the molecular switch for Hailey-Hailey disease manifestation. Experimental dermatology. 2011 Nov:20(11):932-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01359.x. Epub 2011 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 21913998]

Wootton LL, Argent CC, Wheatley M, Michelangeli F. The expression, activity and localisation of the secretory pathway Ca2+ -ATPase (SPCA1) in different mammalian tissues. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2004 Aug 30:1664(2):189-97 [PubMed PMID: 15328051]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMissiaen L, Dode L, Vanoevelen J, Raeymaekers L, Wuytack F. Calcium in the Golgi apparatus. Cell calcium. 2007 May:41(5):405-16 [PubMed PMID: 17140658]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChave TA, Milligan A. Acute generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2002 Jun:27(4):290-2 [PubMed PMID: 12139673]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKostaki D, Castillo JC, Ruzicka T, Sárdy M. Longitudinal leuconychia striata: is it a common sign in Hailey-Hailey and Darier disease? Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2014 Jan:28(1):126-7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12133. Epub 2013 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 23464982]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDadban A, Guillot B. Oesophageal involvement in familial benign chronic pemphigus. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2006:86(3):252-3 [PubMed PMID: 16710588]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOğuz O, Gökler G, Ocakoğlu O, Oğuz V, Demirkesen C, Aydemir EH. Conjunctival involvement in familial chronic benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease). International journal of dermatology. 1997 Apr:36(4):282-5 [PubMed PMID: 9169328]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVáclavínková V, Neumann E. Vaginal involvement in familial benign chronic pemphigus (Morbus Hailey-Hailey). Acta dermato-venereologica. 1982:62(1):80-1 [PubMed PMID: 6175148]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHwang LY, Lee JB, Richard G, Uitto JJ, Hsu S. Type 1 segmental manifestation of Hailey-Hailey disease. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003 Oct:49(4):712-4 [PubMed PMID: 14512922]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePoblete-Gutiérrez P, Wiederholt T, König A, Jugert FK, Marquardt Y, Rübben A, Merk HF, Happle R, Frank J. Allelic loss underlies type 2 segmental Hailey-Hailey disease, providing molecular confirmation of a novel genetic concept. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004 Nov:114(10):1467-74 [PubMed PMID: 15545997]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNanda A, Khawaja F, Al-Sabah H, Happle R. Type 2 segmental Hailey-Hailey disease with systematized bilateral arrangement. International journal of dermatology. 2014 Apr:53(4):476-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05586.x. Epub 2013 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 24320931]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGisondi P, Sampogna F, Annessi G, Girolomoni G, Abeni D. Severe impairment of quality of life in Hailey-Hailey disease. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2005:85(2):132-5 [PubMed PMID: 15823906]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHarris A, Burge SM, Dykes PJ, Finlay AY. Handicap in Darier's disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. The British journal of dermatology. 1996 Dec:135(6):959-63 [PubMed PMID: 8977719]

Finlay AY, Kelly SE. Psoriasis--an index of disability. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 1987 Jan:12(1):8-11 [PubMed PMID: 3652510]

Oliveira A, Arzberger E, Pimentel B, de Sousa VC, Leal-Filipe P. Dermoscopic and reflectance confocal microscopic presentation of Hailey-Hailey disease: A case series. Skin research and technology : official journal of International Society for Bioengineering and the Skin (ISBS) [and] International Society for Digital Imaging of Skin (ISDIS) [and] International Society for Skin Imaging (ISSI). 2018 Feb:24(1):85-92. doi: 10.1111/srt.12394. Epub 2017 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 28782140]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRogner DF, Lammer J, Zink A, Hamm H. Darier and Hailey-Hailey disease: update 2021. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2021 Oct:19(10):1478-1501. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14619. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34661345]

Bakaa L, Pernica JM, Couban RJ, Tackett KJ, Burkhart CN, Leins L, Smart J, Garcia-Romero MT, Elizalde-Jiménez IG, Herd M, Asiniwasis RN, Boguniewicz M, De Benedetto A, Chen L, Ellison K, Frazier W, Greenhawt M, Huynh J, LeBovidge J, Lind ML, Lio P, O'Brien M, Ong PY, Silverberg JI, Spergel JM, Wang J, Begolka WS, Schneider L, Chu DK. Bleach baths for atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis including unpublished data, Bayesian interpretation, and GRADE. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2022 Jun:128(6):660-668.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.03.024. Epub 2022 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 35367346]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePagliarello C, Paradisi A, Dianzani C, Paradisi M, Persichetti P. Topical tacrolimus and 50% zinc oxide paste for Hailey-Hailey disease: less is more. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2012 Jul:92(4):437-8. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1297. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22293917]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang HJ, Growcock AC, Tang TH, O'Hara J, Huang YW, Aronstam RS. Zinc oxide nanoparticle disruption of store-operated calcium entry in a muscarinic receptor signaling pathway. Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2010 Oct:24(7):1953-61. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.08.005. Epub 2010 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 20708676]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUmar SA, Bhattacharjee P, Brodell RT. Treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease with tacrolimus ointment and clobetasol propionate foam. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2004 Mar-Apr:3(2):200-3 [PubMed PMID: 15098980]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSand C, Thomsen HK. Topical tacrolimus ointment is an effective therapy for Hailey-Hailey disease. Archives of dermatology. 2003 Nov:139(11):1401-2 [PubMed PMID: 14623698]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRabeni EJ, Cunningham NM. Effective treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease with topical tacrolimus. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002 Nov:47(5):797-8 [PubMed PMID: 12399782]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReuter J, Termeer C, Bruckner-Tuderman L. [Tacrolimus--a new therapeutic option for Hailey-Hailey-disease?]. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2005 Apr:3(4):278-9 [PubMed PMID: 16370477]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRocha Paris F, Fidalgo A, Baptista J, Caldas LL, Ferreira A. Topical tacrolimus in Hailey-Hailey disease. International journal of tissue reactions. 2005:27(4):151-4 [PubMed PMID: 16440577]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePersić-Vojinović S, Milavec-Puretić V, Dobrić I, Rados J, Spoljar S. Disseminated Hailey-Hailey disease treated with topical tacrolimus and oral erythromycin: Case report and review of the literature. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC. 2006:14(4):253-7 [PubMed PMID: 17311740]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBianchi L, Chimenti MS, Giunta A. Treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease with topical calcitriol. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004 Sep:51(3):475-6 [PubMed PMID: 15337998]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDammak A, Camus M, Anyfantakis V, Guillet G. Successful treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease with topical 5-fluorouracil. The British journal of dermatology. 2009 Oct:161(4):967-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09408.x. Epub 2009 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 19663874]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTang MB, Tan ES. Hailey-Hailey disease: effective treatment with topical cadexomer iodine. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2011 Oct:22(5):304-5. doi: 10.3109/09546631003762670. Epub 2010 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 20673150]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLe Saché-de Peufeilhoux L, Raynaud E, Bouchardeau A, Fraitag S, Bodemer C. Familial benign chronic pemphigus and doxycycline: a review of 6 cases. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2014 Mar:28(3):370-3. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12016. Epub 2012 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 23106313]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSfecci A, Orion C, Darrieux L, Tisseau L, Safa G. Extensive Darier Disease Successfully Treated with Doxycycline Monotherapy. Case reports in dermatology. 2015 Sep-Dec:7(3):311-5. doi: 10.1159/000441467. Epub 2015 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 26594170]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePettit C, Ulman CA, Spohn G, Kaffenberger J. A case of segmental Darier disease treated with doxycycline monotherapy. Dermatology online journal. 2018 Mar 15:24(3):. pii: 13030/qt2827h6qq. Epub 2018 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 29634885]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChauhan P, Meena D, Hazarika N, Mrigpuri S, Parsad D. Generalized Hailey-Hailey disease with flexural keratotic papules: An interesting presentation and remarkable response with minocycline. Dermatologic therapy. 2019 Jul:32(4):e12945. doi: 10.1111/dth.12945. Epub 2019 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 31012213]

Sapadin AN, Fleischmajer R. Tetracyclines: nonantibiotic properties and their clinical implications. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006 Feb:54(2):258-65 [PubMed PMID: 16443056]

Johnson B. Benign familial chronic pemphigus treated with dapsone. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1972 Jul:64(4):326-7 [PubMed PMID: 5042991]

Kellermayer R, Szigeti R, Keeling KM, Bedekovics T, Bedwell DM. Aminoglycosides as potential pharmacogenetic agents in the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2006 Jan:126(1):229-31 [PubMed PMID: 16417242]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang S, Yang Z, Liu Y, Zhao MT, Zhao J, Zhang H, Liu ZY, Wang XL, Ma L, Yang YH. Application of topical gentamicin-a new era in the treatment of genodermatosis. World journal of pediatrics : WJP. 2021 Dec:17(6):568-575. doi: 10.1007/s12519-021-00469-2. Epub 2021 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 34787828]

Mayuzumi N, Ikeda S, Kawada H, Ogawa H. Effects of drugs and anticytokine antibodies on expression of ATP2A2 and ATP2C1 in cultured normal human keratinocytes. The British journal of dermatology. 2005 May:152(5):920-4 [PubMed PMID: 15888147]

Arora H, Bray FN, Cervantes J, Falto Aizpurua LA. Management of familial benign chronic pemphigus. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2016:9():281-290 [PubMed PMID: 27695354]

Naidoo K, Tighe I, Barrett P, Bajaj V. Acitretin as a successful treatment for Hailey-Hailey disease. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2019 Jun:44(4):450-452. doi: 10.1111/ced.13762. Epub 2018 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 30280408]

Vasudevan B, Verma R, Badwal S, Neema S, Mitra D, Sethumadhavan T. Hailey-Hailey disease with skin lesions at unusual sites and a good response to acitretin. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2015 Jan-Feb:81(1):88-91. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.148600. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25566918]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBerger EM, Galadari HI, Gottlieb AB. Successful treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease with acitretin. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2007 Jul:6(7):734-6 [PubMed PMID: 17763599]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLapa T, Breslavets M. Treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease with narrowband phototherapy and acitretin: A case report. SAGE open medical case reports. 2019:7():2050313X19845221. doi: 10.1177/2050313X19845221. Epub 2019 May 2 [PubMed PMID: 31105943]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArjona-Aguilera C, Jiménez-Gallo D, Villegas-Romero I, Valenzuela-Ubiña S, Linares-Barrios M. Subcutaneous methotrexate for Hailey-Hailey disease: two case reports and review of the literature. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2021 Feb:19(2):278-281. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14198. Epub 2020 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 32743934]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBen Lagha I, Ashack K, Khachemoune A. Hailey-Hailey Disease: An Update Review with a Focus on Treatment Data. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2020 Feb:21(1):49-68. doi: 10.1007/s40257-019-00477-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31595434]

Schwaiger K, Neureiter J, Neureiter D, Hladik M, Wechselberger G. Hailey-Hailey Disease and Reduction Mammoplasty: Surgical Treatment of a Gene Mutation. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2018 Feb:42(1):331-332. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-0963-3. Epub 2017 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 28916958]

Menz P, Jackson IT, Connolly S. Surgical control of Hailey-Hailey disease. British journal of plastic surgery. 1987 Nov:40(6):557-61 [PubMed PMID: 3318985]

Zachariae H. Dermabrasion of Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier's disease. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1992 Jul:27(1):136 [PubMed PMID: 1619066]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFarahnik B, Blattner CM, Mortazie MB, Perry BM, Lear W, Elston DM. Interventional treatments for Hailey-Hailey disease. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017 Mar:76(3):551-558.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.039. Epub 2016 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 27745906]

König A, Hörster S, Vakilzadeh F, Happle R. Type 2 segmental manifestation of Hailey-Hailey disease: poor therapeutic response to dermabrasion is due to severe involvement of adnexal structures. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2000 Jun:10(4):265-8 [PubMed PMID: 10846251]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHamm H, Metze D, Bröcker EB. Hailey-Hailey disease. Eradication by dermabrasion. Archives of dermatology. 1994 Sep:130(9):1143-9 [PubMed PMID: 8085869]

LeBlanc KG Jr, Wharton JB, Sheehan DJ. Refractory Hailey-Hailey disease successfully treated with sandpaper dermabrasion. Skinmed. 2011 Jul-Aug:9(4):263-4 [PubMed PMID: 21980715]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHochwalt PC, Christensen KN, Cantwell SR, Hocker TL, Otley CC, Brewer JD, Arpey CJ, Roenigk RK, Baum CL. Carbon dioxide laser treatment for Hailey-Hailey disease: a retrospective chart review with patient-reported outcomes. International journal of dermatology. 2015 Nov:54(11):1309-14. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12991. Epub 2015 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 26341946]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePretel-Irazabal M, Lera-Imbuluzqueta JM, España-Alonso A. Carbon dioxide laser treatment in Hailey-Hailey disease: a series of 8 patients. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2013 May:104(4):325-33. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2013.03.004. Epub 2013 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 23582735]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFalto-Aizpurua LA, Griffith RD, Yazdani Abyaneh MA, Nouri K. Laser therapy for the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease: a systematic review with focus on carbon dioxide laser resurfacing. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2015 Jun:29(6):1045-52. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12875. Epub 2014 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 25418614]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHunt KM, Jensen JD, Walsh SB, Helms ME, Soong VY, Jacobson ES, Sami N, Huang CC, Theos A, Northington ME. Successful treatment of refractory Hailey-Hailey disease with a 595-nm pulsed dye laser: a series of 7 cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015 Apr:72(4):735-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25773417]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDowns A. Smoothbeam laser treatment may help improve hidradenitis suppurativa but not Hailey-Hailey disease. Journal of cosmetic and laser therapy : official publication of the European Society for Laser Dermatology. 2004 Nov:6(3):163-4 [PubMed PMID: 15545102]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlsahli M, Debu A, Girard C, Bessis D, Du Thanh A, Guillot B, Dereure O. Is photodynamic therapy a relevant therapeutic option in refractory benign familial pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease)? A series of eight patients. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2017 Nov:28(7):678-682. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1308461. Epub 2017 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 28301978]

Scarabello A, Pulvirenti C, Adebanjo GAR, Parisella FR, Chello C, Tammaro A. Photodynamic therapy with 5 aminolaevulinic acid: A promising therapeutic option for the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy. 2022 Jun:38():102794. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2022.102794. Epub 2022 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 35247621]

Donohoe C, Senge MO, Arnaut LG, Gomes-da-Silva LC. Cell death in photodynamic therapy: From oxidative stress to anti-tumor immunity. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Reviews on cancer. 2019 Dec:1872(2):188308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.07.003. Epub 2019 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 31401103]

Dreyfus I, Maza A, Rodriguez L, Merlos M, Texier H, Rousseau V, Sommet A, Mazereeuw-Hautier J. Botulinum toxin injections as an effective treatment for patients with intertriginous Hailey-Hailey or Darier disease: an open-label 6-month pilot interventional study. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2021 Feb 18:16(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01710-x. Epub 2021 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 33602313]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBernards M, Korge BP. Desmosome assembly and keratin network formation after Ca2+/serum induction and UVB radiation in Hailey-Hailey keratinocytes. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2000 May:114(5):1058-61 [PubMed PMID: 10792570]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVanderbeck KA, Giroux L, Murugan NJ, Karbowski LM. Combined therapeutic use of oral alitretinoin and narrowband ultraviolet-B therapy in the treatment of hailey-hailey disease. Dermatology reports. 2014 Feb 17:6(1):5604. doi: 10.4081/dr.2014.5604. Epub 2014 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 25386331]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNandini As, Mysore V. Hailey-hailey disease: a novel method of management by radiofrequency surgery. Journal of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery. 2008 Jul:1(2):92-3. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.44167. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20300352]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeung N, Cardones AR, Larrier N. Long-term improvement of recalcitrant Hailey-Hailey disease with electron beam radiation therapy: Case report and review. Practical radiation oncology. 2018 Sep-Oct:8(5):e259-e261. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2018.02.011. Epub 2018 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 29907515]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaniszewska M, Rovner R, Arshanapalli A, Tung R. Oral glycopyrrolate for the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. JAMA dermatology. 2015 Mar:151(3):328-9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.4578. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25651401]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBindernagel R, Kimmis BD, Liu D. Use of topical 2.4% glycopyrronium tosylate in familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease). Dermatology online journal. 2020 Oct 15:26(10):. pii: 13030/qt01j7n9qw. Epub 2020 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 33147680]

Albers LN, Arbiser JL, Feldman RJ. Treatment of Hailey-Hailey Disease With Low-Dose Naltrexone. JAMA dermatology. 2017 Oct 1:153(10):1018-1020. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2446. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28768313]

Ibrahim O, Hogan SR, Vij A, Fernandez AP. Low-Dose Naltrexone Treatment of Familial Benign Pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey Disease). JAMA dermatology. 2017 Oct 1:153(10):1015-1017. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2445. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28768314]

Yoto A, Makino T, Mizawa M, Matsui Y, Takemoto K, Furukawa F, Kataoka K, Nakano H, Sawamura D, Shimizu T. Two cases of Hailey-Hailey disease effectively treated with apremilast and a review of reported cases. The Journal of dermatology. 2021 Dec:48(12):1945-1948. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16178. Epub 2021 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 34569085]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRiquelme-Mc Loughlin C, Iranzo P, Mascaró JM Jr. Apremilast in benign chronic pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease). Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2020 Aug:45(6):737-739. doi: 10.1111/ced.14225. Epub 2020 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 32198945]

Antoñanzas J, Tomás-Velázquez A, Rodríguez-Garijo N, Estenaga Á, Salido-Vallejo R. Apremilast in combination with botulinum toxin-A injection for recalcitrant Hailey-Hailey disease. International journal of dermatology. 2022 May:61(5):600-602. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15953. Epub 2021 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 34705274]

Siliquini N, Deboli T, Marchetti Cautela J, Mangia A, Fraccalvieri M, Dapavo P, Quaglino P, Ribero S. Combination of dermabrasion and Apremilast for Hailey-Hailey disease. Italian journal of dermatology and venereology. 2021 Dec:156(6):727-728. doi: 10.23736/S2784-8671.20.06540-2. Epub 2020 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 32129590]

Alzahrani N, Grossman-Kranseler J, Swali R, Fiumara K, Zancanaro P, Tyring S, Rosmarin D. Hailey-Hailey disease treated with dupilumab: a case series. The British journal of dermatology. 2021 Sep:185(3):680-682. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20475. Epub 2021 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 33971025]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlamon-Reig F, Serra-García L, Bosch-Amate X, Riquelme-Mc Loughlin C, Mascaró JM Jr. Dupilumab in Hailey-Hailey disease: a case series. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2022 Oct:36(10):e776-e779. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18350. Epub 2022 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 35734956]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSasaki T, Kano R, Sato H, Nakamura Y, Watanabe S, Hasegawa A. Effects of staphylococci on cytokine production from human keratinocytes. The British journal of dermatology. 2003 Jan:148(1):46-50 [PubMed PMID: 12534593]

Cockayne SE, Rassl DM, Thomas SE. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in Hailey-Hailey disease of the vulva. The British journal of dermatology. 2000 Mar:142(3):540-2 [PubMed PMID: 10735968]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOchiai T, Honda A, Morishima T, Sata T, Sakamoto H, Satoh K. Human papillomavirus types 16 and 39 in a vulval carcinoma occurring in a woman with Hailey-Hailey disease. The British journal of dermatology. 1999 Mar:140(3):509-13 [PubMed PMID: 10233276]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence