Introduction

The temporal lobe of the brain is often referred to as the neocortex. It forms the cerebral cortex in conjunction with the occipital lobe, the parietal lobe, and the frontal lobe. It is located mainly in the middle cranial fossa, a space located close to the skull base. It is anterior to the occipital lobe and posterior to the frontal lobe. It is found inferior to the lateral fissure, also known as the Sylvian fissure or the lateral sulcus. The temporal lobe subdivides further into the superior temporal lobe, the middle temporal lobe, and the inferior temporal lobe. It houses several critical brain structures including the hippocampus and the amygdala.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

In order to fully comprehend the temporal lobe, it is best to analyze it also through its functional connectivity, not just its gross structure. The idea that certain parts of the brain perform certain functions is called localizationism. Localizationism does not always correspond to predictions of functions. Connections define functions. On the other hand, without understanding function, connections of structures are useless. Hence, in order to see the whole picture, structure, connections, and functions must be correlated.[1][2]

Brodmann's area has clearly defined 47 areas. However, due to advances in technology and recent studies, the Human Connectome Project (HCP) was able to discover 180 parcellations of the human cortex. Of the 47 Brodmann's areas, only 23 were retained. The rest were redefined or subdivided further into more specific areas (e.g. anterior, posterior, ventral, dorsal).[1]

The temporal lobe can be divided through its traditional Broadmann's area or simply by the superior, middle and inferior temporal gyrus (STG, MTG, ITG, respectively), parahippocampal/entorhinal gyri and fusiform gyrus. However, it has been reorganized into a new scheme due to a lack of basis on its functional or organizational anatomy.[3] Based on previous studies, major association fiber tracts has been identified:

- Uncinate fasciculus (UF)

- Inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF)

- Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF)

- Middle longitudinal fasciculus (MdLF)

- Arcuate fasciculus (AF) and cingulum

- Two main commissural fibers - corpus callosum and anterior commissure (AC)

Meanwhile, 8 cognitive domains were identified via functional imaging with their associated part of the temporal lobe:

- Speech perception - posterior superior temporal gyrus

- Speech production - posterior superior temporal gyrus

- Hearing - posterior superior temporal gyrus

- Episodic memory - medial structures

- Phonological - dorsal and posterior structures

- Semantic - ventral temporal lobe

- Social - two areas in the temporal lobe

- Visual - temporo-occipital junction [4]

HCP proposes a new scheme that considers its functional connectivity:

- Lateral: for semantic processing, SLF/arcuate system areas (superior temporal sulcus [STS], temporal area 1 [TE1], PHT, temporal area 2 anterior [TE2a], superior temporal gyrus region a [STGa])

- Polar: for emotional processing and other functions, uncinate connected areas (temporal gyrus dorsal [TGd] and temporal gyrus ventral [TGv])

- Inferior: for visual processing, ILF connected areas (TE2a, temporal area 2 posterior [TE2p], TF and perirhinal ectorhinal cortex [PeEC])

- Medial: for memory and visuospatial processing, hippocampus and cingulate system

HCP categorizes association cortices, auditory area 4 (A4) and auditory area 5 (A5), and temporal region A (TA2) found in STG in the insula and opercular cortex.[3]

Lateral Temporal System

It is notable that the lateral and medial structures do not have connections as the anatomy of white matter runs anterior-posterior more than medial-lateral. Functionally and structurally, it appears that its parcellations cluster into two: superior cluster, whose fibers end in the posterior inferior frontal gyrus, include STS and TE1a; inferior cluster, whose fibers end in superior parts of the frontal lobe, includes TE1m, TE1p, TE2a, PHT.[3]

The superior temporal sulcus (STS) has four parts: STS dorsal anterior (STSda), STS dorsal posterior (STSdp), STS ventral anterior (STSva) and STS ventral posterior (STSvp). The four parts of the STS have functional connectivity to different parcellations of the frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital lobes and insula opercular area. Teva has additional functional connectivity to the hippocampus. Meanwhile, it has white matter connections (structural connectivity) to arcuate/superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), the "u" fibers of the occipitotemporal system and middle longitudinal fasciculus (MdLF). STSdp does not have structural connectivity to MdLF. STS has numerous functions, including motion, speech and facial processing, language comprehension and audiovisual integration. It has also been related to the theory of mind. Each part of the STS has different levels of activation depending on the particular function.[3][5]

Temporal area 1 anterior (TE1a), middle (TE1m) and posterior (TE1p) are found in the MTG. All three areas have functional connectivity to different parcellations of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes. TE1a has additional functional connectivity to some STS areas, temporal gyrus ventral (TGv), entorhinal cortex (EC), and hippocampus. All three areas have white matter connections (structural connectivity) to "u" fibers of the occipitotemporal system and arcuate/SLF. TE1a has an additional white matter connection to inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF). These areas are primarily responsible for processing visual information, including working memory for short term visual maintenance of information.[3][5]

Area PHT is located on the subcentral gyrus and involves the operculum and Sylvian Fissure. It has functional connectivity to numerous parcellations in the frontal lobe, insula opercular area, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes. It has white matter connections to the arcuate/SLF. The part that lies on the posterior MTG is useful in conscious retrieval of conceptual knowledge while the anterior part is for automatic retrieval of semantic information.[3]

Superior temporal gyrus region 'a' (STGa) is found on the superior temporal gyrus at its anterior superior surface. It is functionally connected to different parcellations of the insula opercular region and temporal lobe. It has white matter connections (structural connectivity) to inferior longitudinal fasciculus and local parcellations. STG areas are functionally involved in perceptual and conceptual acoustic sound processing.[6]

Polar Temporal System

The temporal gyrus areas (TG) refers to the temporal polar area. It is composed of the TG dorsal (TGd) and TG ventral (TGv). They are both functionally connected to each other. TGd is also functionally connected to different parcellations of the frontal lobe, STS, STGa, PeEc, hippocampus and TE1a. Meanwhile, TGv is functionally connected to area 45. Both have white matter connections (structural connectivity) to ILF but TGd has white matter connection to uncinate fasciculus as well. Another study divides the temporal area into 4 major subregions: a) dorsal, mostly language and auditory/somatosensory networks b) ventromedial, mostly visual network c) medial, connected to paralimbic structures and d) anterolateral, associated with a default-semantic network. These areas have many important functions such as processing of language, social cues, and emotions, facial recognition (auditory and visual aspects), emotional processing of different stimuli (auditory, olfactory and visual) and theory of mind. They differ in the level of activation during motor tasks where TGd is deactivated while TGv is activated.[3][5][7]

Inferior Temporal System

Temporal area 2 anterior (TE2a) and temporal area 2 posterior (TE2p) are found in the ITG. These areas have functional connectivity to different parcellations of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes. TE2p has additional functional connectivity to the occipital lobe. Both have white matter connections (structural connectivity) to arcuate/SLF. TE2a has white matter connections to ILF while TE2p has white matter connections to local parcellations. These areas appear to function in vision.[3][5]

Area TF is found on the occipitotemporal sulcus and anterior fusiform gyrus. It has functional connectivity to TE2p and perirhinal ectorhinal cortex (PeEC) and has white matter connections to the arcuate/SLF and ILF. Studies suggest that it is responsible for working memory maintenance. The fusiform gyrus is also relevant for reading, object recognition, and facial recognition.[3]

Area PeEC is located on the uncus, at its anterior portions and inferior surface, extending to the collateral sulcus. It has functional connectivity to numerous parcellations of the frontal lobe, occipital lobe, and parietal lobe, also to areas PHA2, PHA3, TF, and EC. It has white matter connections to ILF. Its function contributes to declarative memories and semantic knowledge. It also incorporates item information with spatio-temporal information.[3]

Medial Temporal System

Medial temporal areas include area PreS, Area EC, and parahippocampal areas (PHA1, PHA2, PHA3).[3]

Area PreS is located on the posterosuperior surface of the parahippocampal gyrus. It has functional connectivity to the hippocampus, numerous parcellations in the frontal lobe, parietal lobe and occipital lobe and local functional connectivity to PHA1 and PHA2. Area PreS has white matter connections to the cingulum, precuneus and occipital lobe, as well as EC and PeEc. Its function is mainly involved in spatial information processing.[3]

Area EC is located on the uncus, at its medial posterior surface. It has functional connectivity to a number of parcellations of the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and parietal lobe, as well as the hippocampus. It has white matter connections (structural connectivity) to the cingulum. It is responsible for memory consolidation and the rapid encoding of new associations.[3]

Area PHA1 is found on the medial portion of the parahippocampal gyrus, PHA2 on the inferior surface and PHA3 inside the collateral sulcus of the parahippocampal gyrus. It has functional connectivity to different parcellations in the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes. PHA1 however, does not have functional connectivity to the occipital lobe. As for their white matter connections, PHA1 has local structural connectivity while PHA2 and PHA3 have white matter connections to ILF. All of them are important in episodic memory and visuospatial processing. They differ in the level of activity in face recognition where PHA1 is less deactivated while PHA2 is more deactivated. Meanwhile, PHA3 has more activity in tool-related recognition tasks.[3]

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is found deep into the medial temporal lobe. Grossly, it resembles a seahorse.[2] It can be divided functionally into ventral, intermediate and dorsal parts. Furthermore, it can be divided into the dentate gyrus, CA1, and CA3.[8] On cross-section, it demonstrates its classic hippocampal anatomical connectivity--"trisynaptic loop". Its major cortical input is through the entorhinal cortex. The path to the dentate gyrus region (DG) is its strongest projections. DG projects to the CA3 region, which projects to the CA1 region, which projects back to the entorhinal cortex, completing the loop. These occur via the mossy fiber pathway and the Schaffer Collateral pathway. Other major inputs aside from the entorhinal cortex are the perirhinal cortex, the postrhinal cortex, medial septum, locus coeruleus, nucleus reuniens, raphe nucleus, and amygdala. The major output is from CA1 regions to the lateral septum. This is via the fornix.[2][8][9]

The hippocampus is responsible for creating declarative memories--those that can be consciously thought of and verbalized. Declarative memory can be episodic and semantic. Episodic memory is the ability to remember a specific occasion in the past in its specific time and place. Example, "This evening, in my living room, I ate steak for dinner". Meanwhile, semantic memory is the ability to recall general facts about the world. For example, "Bread is made of flour and yeast and is typical for breakfast". Some studies speculate that the hippocampus is crucial for episodic memory while the medial temporal lobe is for semantic memory.[2]

Amygdala

The amygdala is an almond-like shape structure found in the medial temporal lobe 17956742. It is composed of subareas or nuclei which can be divided into three: 1. basolateral amygdala group (lateral, basal, and basomedial nuclei) 2. cortical group (cortical nuclei and nucleus of the lateral olfactory tract) and 3. centromedial group (medial and central nuclei).[8][10] The nuclei are distinguished among them based on their histological criteria (i.e., the shape and size of stained cells, density, chemical signatures).[11] The lateral amygdala is the major site that receives inputs from all the sensory systems. It is connected reciprocally with cortical regions (midline and orbital prefrontal cortices and hippocampus and sensory association areas). The sensory input terminates mostly in the dorsal subnucleus which communicates with the medial and ventrolateral areas. On the other hand, the dominant output region is the central nucleus, especially for the expression of emotional responses and other associated physiologic responses. Other outputs of the lateral amygdala are nucleus accumbens and bed nucleus of stria terminalis. The inputs and outputs communicate through intraamygdala connections.[11][10]

The most associated function of the amygdala is fear. However, the amygdala is also implicated other various emotional functions such as anxiety reward processing, reward learning and motivation, and drug addiction. Also implicated are aggression, maternal, sexual and ingestive behaviors (eating and drinking). Other than emotion, the amygdala also plays a role in the regulation of various cognition like perception, attention and explicit memory. It is also implicated in psychiatric diseases, addiction, and autism.[11][8][10][12]

The amygdala and hippocampus are two different systems that collide when emotion meets memory.[8] Studies show that the main neurons associated with hippocampal and amygdala relations are glutamatergic pyramidal neurons. However, other studies suggest that it may be mediated by inhibitory GABAergic long-range nonpyramidal projection neuron (LRNP).[12]

Embryology

The development of the temporal lobe, part of the forebrain, is linked closely to the development of the cerebral cortex. The embryonic ectoderm contains a specialized part known as the neural plate. The neural plate folds to create the neural tube. The neural tube houses the four ventricles, which are closed spaces containing cerebrospinal fluid, within the brain. The most anterior portion of the neural plate, the prosencephalon, eventually forms the cerebral cortex. At about three and a half weeks' gestation, the three portions of the brain become apparent from the neural plate. These portions include the prosencephalon, mesencephalon, and rhombencephalon. At about six weeks, a bend in the neural plate is visible. At seven weeks, the hemispheres of the brain start to become apparent. At fourteen weeks, the hemispheres are clearly visible, and at five months they have grown to occupy most of the brain. At eight months, the characteristic gyri and sulci, the ridges and valleys, of the cerebral cortex become clear.

At 10-15 weeks, fissures (Sylvian and interhemispheric fissure), central sulcus and insular indentation appear. At 20-23 weeks, superior temporal gyrus and sulcus develop while major hemispheric growth occurs simultaneously. At 27 weeks until full term, frontal, parietal and temporal lobes start to cover the insula until the operculum achieves full closure. Operuclar closure occurs from the posterior to anterior direction. Meanwhile, gyrification of the temporal lobe begins at 10-20 weeks of fetal life and continues to at least until the first postnatal year.[13]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The temporal lobe receives oxygenated blood via two primary sources, the internal carotid system and the vertebrobasilar artery. The internal carotid system contains the anterior choroidal artery and the middle cerebral artery. The blood flow from the anterior choroidal artery supplies the uncus, amygdala, and the anterior parahippocampal gyrus. The middle cerebral artery branches into the temporopolar artery, anterior temporal artery, middle temporal artery, and posterior temporal artery. It supplies the temporal pole as well as the superior and inferior portions of the temporal gyri. Blood flow from the vertebrobasilar system supplies the inferior surface of the temporal lobe from the temper-occipital artery.

Blood is drained from the temporal lobe by veins via two major routes. One route involves blood passing from the temporal lobe anteriorly to superficial middle cerebral vein. From there, it moves into the inferior anastomotic vein, known as the vein of Labbe, which goes on to join the transverse sinus. The other route involves blood flowing from the interior temporal lobe into the posterior choroidal vein. This vessel then pairs up with the thalamostriate vein from behind the interventricular foramen to form the internal cerebral vein. The internal cerebral vein then joins the basal veins to create the great cerebral vein.[14]

Surgical Considerations

The temporal lobe is crucial in many essential activities such as processing of memory, language, and emotion. There are a lot of areas that are thought of to be "silent" and are likewise regarded as dispensable. Meanwhile, there are regions in the brain that were not previously fully understood such as a sulcus whose parts and surfaces are functionally different and distinct, most notably, the superior temporal sulcus. Most neurosurgeons prefer the trans-sulcal approaches which are believed to be ideal in order to reduce brain transgression into deep targets. However, learning about the important function and significance of the sulci will make a physician reconsider a better option in tumor resection. Therefore, surgery must be performed with due care so as not to affect the critical functions performed by the temporal lobe negatively.[1]

Despite the risk associated with surgery of and around the temporal lobe, it is often performed to treat temporal lobe epilepsy. In this condition, patients suffer seizures originating in the temporal lobe. Physicians can remove a section of the lobe to eliminate or significantly terminate seizures in >80% of patients.[12] Using different functional tests including Wada, functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and neuropsychological evaluations minimize the risk of the procedure. These tests confirm critical sections of the brain and help draw surgical boundaries. Due to the use of these precautionary measures, the surgery is both effective and safe. A study of 215 patients who had temporal lobe surgery showed that 89% were either seizure-free or experienced a significantly reduced average number of seizures. No postoperative mortality was observed.[15] Despite its success, there is no consensus regarding the best surgical approach. The surgical technique choice remains to be the surgeon's preference.[16] In refractory temporal epilepsy, selective transcortical amygdalohippocampectomy should be considered as a possible treatment.[17]

Clinical Significance

Temporal lobe lesions can be categorized into 3 based on their MRI features.

- Unilateral volume loss

- Mesial temporal sclerosis

- Old infarction

- Remote brain injury

- Prior surgery

- Bilateral pathology

- Alzheimer disease

- Fronto-temporal dementia

- Age-related volume loss

- Mesial temporal sclerosis (10%)

- Limbic encephalitis

- Postradiation changes

- Space-occupying lesions

- Cystic neoplasia

- Solid neoplasm

- Encephalitis

- Abscess

- Vascular malformations

- Acute infarction

- Acute trauma [17]

Uncontrolled damage to the temporal lobe poses a significant threat to the quality of a patient's life. A review of 56 localized lesions to the temporal lobe showed widespread effects on patients' lives. The most common symptoms observed are mental disturbances generally categorized as a confused state. The secondary ailment of temporal lesions is personality changes, which ranges widely from slight emotional changes to homicidal tendencies. Of lesser frequency but still reported include symptoms of muscular pareses, somatic seizures, psychical seizures, autonomic seizures, visual field defects, and speech disorders.[18] Temporal pole lesions can affect semantic and lexical skills, socio-affective behavior, face recognition and regulation of eating and sexual behavior.[7]

Wernicke aphasia is one clinical presentation of damage to the temporal lobe. It is seen often in patients who have suffered an ischemic stroke to the temporal lobe. Less frequently, it affects patients with infections, trauma, tumors, central nervous system infections, and other degenerative brain conditions. Wernicke aphasia, also known as receptive aphasia, impairs language function. Patients presenting with this aphasia can still speak with normal rate and tone but will often misuse words and form nonsensical sentences. This aphasia is in contrast to Broca aphasia in which patients cannot talk with normal fluency and tone.[19][20]

Damage or dysfunction to the hippocampal region, amygdala and/or their interconnections can cause posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Alzheimer disease and temporal lobe epilepsy.[12]

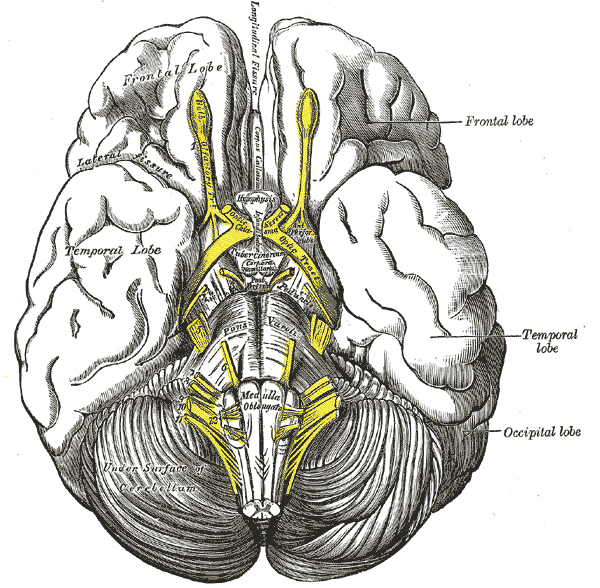

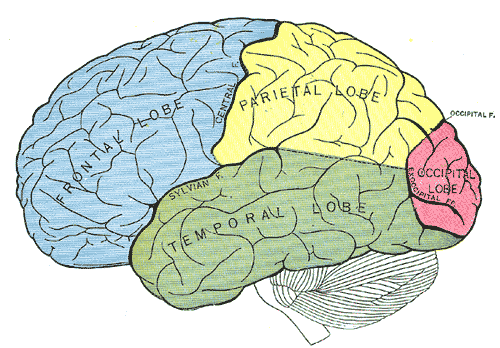

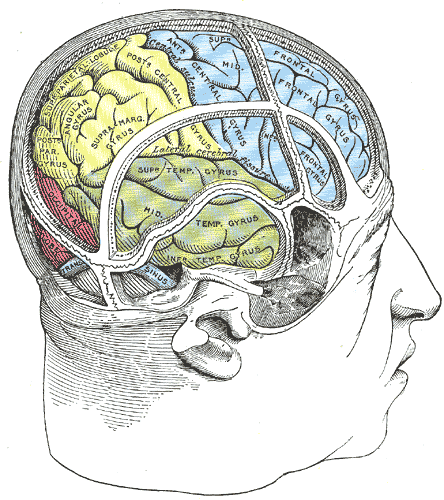

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

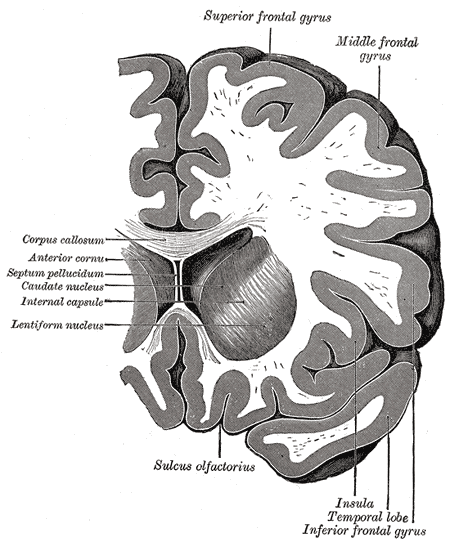

Coronal section through anterior cornua of lateral ventricles, Superior frontal gyrus, Middle Frontal Gyrus, Corpus callosum, Anterior cornua, Septum pellucidum, Caudate nucleus, Internal capsule, Lentiform nucleus, Sulcus olfactorius, Insula, Temporal lobe, Inferior Frontal gyrus

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Baker CM, Burks JD, Briggs RG, Conner AK, Glenn CA, Sali G, McCoy TM, Battiste JD, O'Donoghue DL, Sughrue ME. A Connectomic Atlas of the Human Cerebrum-Chapter 1: Introduction, Methods, and Significance. Operative neurosurgery (Hagerstown, Md.). 2018 Dec 1:15(suppl_1):S1-S9. doi: 10.1093/ons/opy253. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30260422]

Knierim JJ. The hippocampus. Current biology : CB. 2015 Dec 7:25(23):R1116-21. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.049. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26654366]

Baker CM, Burks JD, Briggs RG, Milton CK, Conner AK, Glenn CA, Sali G, McCoy TM, Battiste JD, O'Donoghue DL, Sughrue ME. A Connectomic Atlas of the Human Cerebrum-Chapter 6: The Temporal Lobe. Operative neurosurgery (Hagerstown, Md.). 2018 Dec 1:15(suppl_1):S245-S294. doi: 10.1093/ons/opy260. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30260447]

Bajada CJ,Haroon HA,Azadbakht H,Parker GJM,Lambon Ralph MA,Cloutman LL, The tract terminations in the temporal lobe: Their location and associated functions. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior. 2017 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 27118049]

Baylis GC, Rolls ET, Leonard CM. Functional subdivisions of the temporal lobe neocortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1987 Feb:7(2):330-42 [PubMed PMID: 3819816]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaker CM, Burks JD, Briggs RG, Conner AK, Glenn CA, Robbins JM, Sheets JR, Sali G, McCoy TM, Battiste JD, O'Donoghue DL, Sughrue ME. A Connectomic Atlas of the Human Cerebrum-Chapter 5: The Insula and Opercular Cortex. Operative neurosurgery (Hagerstown, Md.). 2018 Dec 1:15(suppl_1):S175-S244. doi: 10.1093/ons/opy259. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30260456]

Pascual B, Masdeu JC, Hollenbeck M, Makris N, Insausti R, Ding SL, Dickerson BC. Large-scale brain networks of the human left temporal pole: a functional connectivity MRI study. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991). 2015 Mar:25(3):680-702. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht260. Epub 2013 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 24068551]

Yang Y,Wang JZ, From Structure to Behavior in Basolateral Amygdala-Hippocampus Circuits. Frontiers in neural circuits. 2017; [PubMed PMID: 29163066]

Soltesz I, Losonczy A. CA1 pyramidal cell diversity enabling parallel information processing in the hippocampus. Nature neuroscience. 2018 Apr:21(4):484-493. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0118-0. Epub 2018 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 29593317]

Janak PH, Tye KM. From circuits to behaviour in the amygdala. Nature. 2015 Jan 15:517(7534):284-92. doi: 10.1038/nature14188. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25592533]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeDoux J. The amygdala. Current biology : CB. 2007 Oct 23:17(20):R868-74 [PubMed PMID: 17956742]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcDonald AJ, Mott DD. Functional neuroanatomy of amygdalohippocampal interconnections and their role in learning and memory. Journal of neuroscience research. 2017 Mar:95(3):797-820. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23709. Epub 2016 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 26876924]

Goldstein IS, Erickson DJ, Sleeper LA, Haynes RL, Kinney HC. The Lateral Temporal Lobe in Early Human Life. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2017 Jun 1:76(6):424-438. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlx026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28498956]

Kiernan JA. Anatomy of the temporal lobe. Epilepsy research and treatment. 2012:2012():176157. doi: 10.1155/2012/176157. Epub 2012 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 22934160]

Salanova V, Markand O, Worth R. Temporal lobe epilepsy surgery: outcome, complications, and late mortality rate in 215 patients. Epilepsia. 2002 Feb:43(2):170-4 [PubMed PMID: 11903464]

Alonso Vanegas MA, Lew SM, Morino M, Sarmento SA. Microsurgical techniques in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2017 Apr:58 Suppl 1():10-18. doi: 10.1111/epi.13684. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28386927]

Khashper A, Chankowsky J, Del Carpio-O'Donovan R. Magnetic resonance imaging of the temporal lobe: normal anatomy and diseases. Canadian Association of Radiologists journal = Journal l'Association canadienne des radiologistes. 2014 May:65(2):148-57. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2013.05.001. Epub 2013 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 24144924]

WYKE BD. Surgical considerations of the temporal lobes; a clinical report based on a study of fifty-six verified localised lesions of the temporal lobes. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1958 Feb:22(2):117-38 [PubMed PMID: 13509566]

Thompson HE, Robson H, Lambon Ralph MA, Jefferies E. Varieties of semantic 'access' deficit in Wernicke's aphasia and semantic aphasia. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2015 Dec:138(Pt 12):3776-92. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv281. Epub 2015 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 26454668]

Acharya AB, Wroten M. Wernicke Aphasia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722980]