Introduction

Tinnitus is the perception of sound absent an auditory stimulus and is a common complaint in the otologist's office. Tinnitus can be acute or chronic, depending on the underlying pathophysiology. Up to 75% of adults have experienced at least one episode of acute or chronic tinnitus.[1] To make an accurate diagnosis is important to classify tinnitus with a thorough history and physical. There are many ways to categorize tinnitus; one important historical point is to differentiate pulsatile vs. non-pulsatile tinnitus. The most common form of tinnitus is non-pulsatile, and the most common underlying pathophysiology is presbycusis.[2] Since non-pulsatile is much more common than pulsatile tinnitus, the diagnosis and treatment of pulsatile tinnitus can present a challenge for practitioners. Once pulsatile tinnitus has been described, it can be categorized into vascular vs. nonvascular causes. Vascular causes can then be broken down further into arterial vs. venous etiologies. Many times, this difference is possible with history and physical exam, but there is a crucial role for radiographic imaging as well.[3] This activity will discuss the broad etiologies of pulsatile tinnitus as well as describe one way to organize the work-up for this complex symptom. Despite being a relatively uncommon complaint, early detection and treatment are imperative for positive patient outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

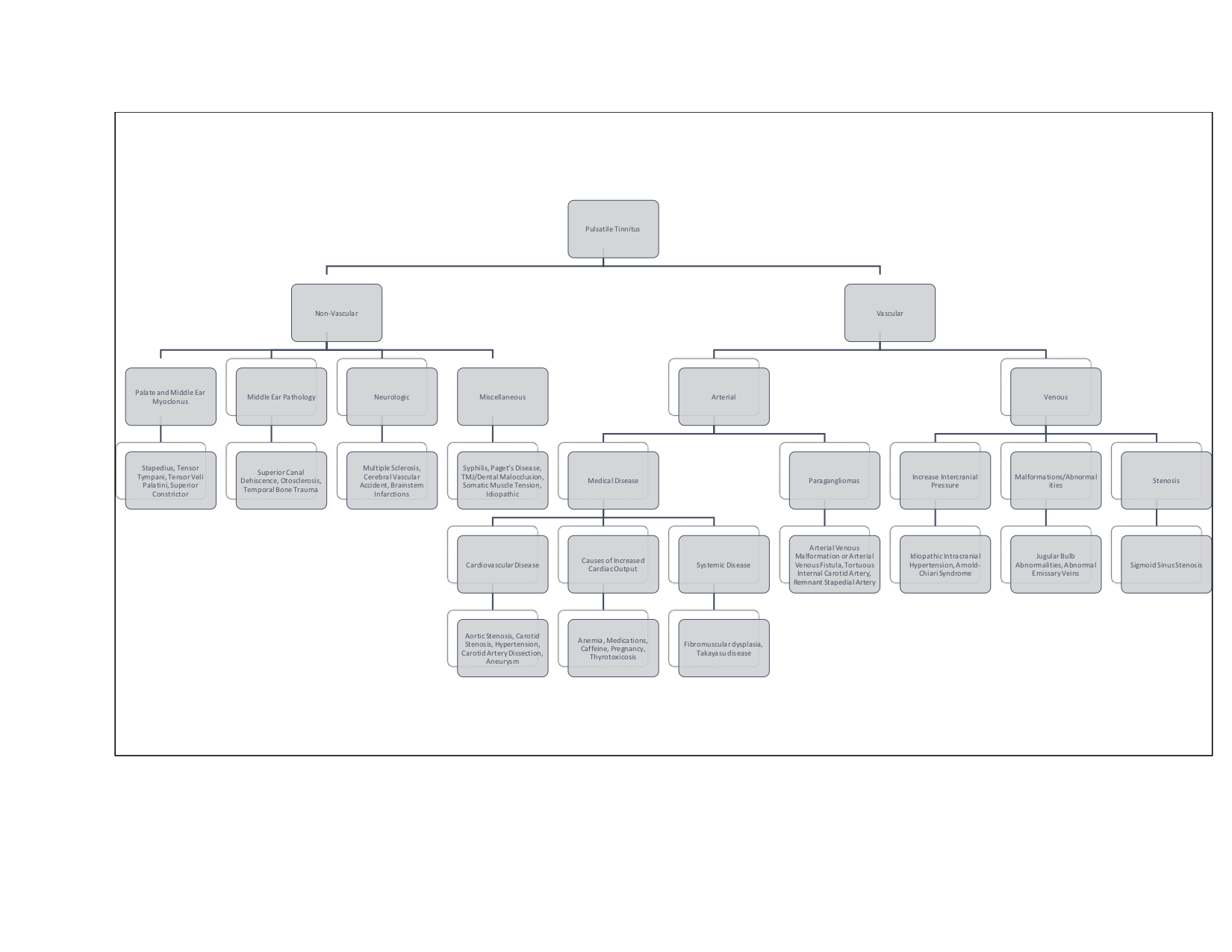

The etiology of pulsatile tinnitus can be broadly broken down into two categories: vascular and non-vascular. Vascular causes can then be subcategorized into arterial vs. venous, with arterial causes being more common.[4] Perhaps the most common cause of intermittent pulsatile tinnitus is uncontrolled hypertension, and appropriate management of this condition is paramount before proceeding with further interventions. Another common arterial cause is turbulent flow through arteries, various conditions can disrupt the laminar flow leading to turbulence, and it is this turbulent flow that patients can hear, causing pulsatile tinnitus. The most common etiology of pulsatile tinnitus is atherosclerotic carotid disease. Stenosis in the carotid arteries will cause turbulent flow through the carotids, which will be perceived by the patient as ipsilateral pulsatile tinnitus. Natural variation in the position of the basilar artery can similarly cause pulsatile tinnitus, even in a normotensive patient without atherosclerotic disease. Stenosis may also be due to more systemic disease such as fibromuscular dysplasia or Takayasu disease, though these are much rarer. Another vascular etiology is paragangliomas, also known as glomus tumors, of the jugular foramen and middle ear, or of the carotid body. This condition may is observable on otoscopy, and patients will usually present with unilateral pulsatile tinnitus that is objectively heard on auscultation of the neck or ear by the examiner. The most common venous cause is idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), also known as pseudotumor cerebri. These patients may have bilateral pulsatile tinnitus; this is most commonly seen in young, obese females who may also complain of vision changes and headaches. The proposed pathophysiology is that patients perceive rhythmic changes in cerebrospinal fluid pressure. The less common non-vascular etiologies include metabolic diseases causing increase cardiac output (such as pregnancy, anemia, and thyrotoxicosis) and myoclonus of palate and middle ear musculature. Figure 1 is a flowchart with a more extensive list of other etiologies that can cause pulsatile tinnitus. It organizes in a way that can help practitioners narrow down the differential, which will, in turn, help guide management decisions.[1][4][2][5][6][3]

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of tinnitus is poorly defined as there is no standard for determining tinnitus in patients. Up to 75% of adults have experienced at least one episode of tinnitus.[2] A recent literature review on tinnitus estimated the prevalence of persistent tinnitus to be between 5.1 to 42.7% with a male predominance and increasing nearly linearly with age.[7] The wide range is likely due to the differences in inclusion criteria from each study evaluated. Prevalence tends to increase in age as presbycusis is a common cause of tinnitus. Less than 10% of tinnitus patients will present with pulsatile tinnitus.[1]

History and Physical

When a patient presents with tinnitus, the most critical step is to obtain a thorough history. One of the most important distinctions to make is if the tinnitus is pulsatile or non-pulsatile. The next step is to determine if the tinnitus is unilateral or bilateral. This distinction will help with directing your questioning and eventually guide your workup. Both pulsatile and non-pulsatile tinnitus can be unilateral or bilateral. Other important questions include the onset of symptoms, aggravating or alleviating factors, duration, and change in symptom quality or severity.[7] Getting a sense of how loud the tinnitus is to the patient may add conditions to the differential. If patients complain of very loud, unbearable pulsatile tinnitus, the clinician should add an arteriovenous malformation to the differential. Tinnitus complaints warrant a thorough otologic history, including inquiring about concurrent symptoms of hearing loss, vertigo, otorrhea, otalgia, noise exposure, and neurological defects in addition to a history of otitis media and head and neck surgeries is very important in building a differential. Practitioners should evaluate the patient’s medication list as certain medications are ototoxic such as antibiotics and chemotherapy agents. Over-the-counter medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, aspirin, and herbal supplements can worsen tinnitus symptoms. Past medical and family history is essential as various medical conditions can manifest with pulsatile tinnitus. A family history of autoimmune diseases is significant as this may raise concern for vasculitis, such as Takayasu disease, which may manifest as pulsatile tinnitus. Some examples include uncontrolled hypertension, which may suggest fibromuscular dysplasia.

The physical exam is essential for patients with pulsatile tinnitus. In general, the physical exam will allow the practitioner to further categorize the pulsatile tinnitus into subjective vs. objective. Every patient should receive an in-depth head and neck exam, paying particular attention to pneumatic otoscopy, cranial nerve exam, and tuning fork exams. Otoscopy may help in identifying paragangliomas, aberrant carotid arteries, otitis media, and eustachian tube dysfunction. Tympanic paragangliomas, also known as glomus tumors, may present as a pulsatile mass on the medial side of the tympanic membrane. A rhythmic motion of the tympanic membrane may be suggestive of tensor tympani myoclonus. Pneumatic otoscopy may suggest otosclerosis or cause nystagmus, which may be indicative of labyrinthine fistula. The palpation of the temporomandibular joint can help identify pathology, which may be contributing to symptoms.[5]

In addition to a head and neck examination, it is important to do a full cardiac examination, including auscultation for carotid bruits. The cardiac examination, along with vitals, can help evaluate causes such as carotid bruits, hypertension, and aortic stenosis. This is also a good time to ascertain if the tinnitus is synchronous with the heartbeat helping to identify underlying arterial pathology.[8] Practitioners should pay special attention to their palpatory exam feeling for any thrills or vascular abnormalities.

Palpation can also help to evaluate if compression changes the patient’s symptoms, which may help differentiate venous vs. arterial etiologies. If compression of arterial structures decreases symptoms, it suggests an arterial cause. Compression of ipsilateral venous structures may decrease symptoms in venous etiologies such as a high-riding jugular bulb, while compression of the contralateral side may increase symptoms. Rotation of the head to the ipsilateral side of the tinnitus may also decrease symptoms in patients with pulsatile tinnitus due to venous pathology. Similarly, the Valsalva maneuver may reduce symptoms with a venous cause.[1][4]

Evaluation

The workup for patients with pulsatile tinnitus should begin with an audiologic evaluation, including pure tone and speech audiometry with tympanograms. If the examiner notes a low-frequency loss of at least 20 dB, it is appropriate to repeat an audiogram with light pressure over the ipsilateral internal jugular vein.[4] The resolution of deficit may be suggestive of IIH. Though the results of basic metabolic tests will likely be normal, they can be used to rule out certain medical diseases that may cause elevated cardiac output causing patients to have pulsatile tinnitus.

Following audiogram and basic labs, clinical suspicion should guide the work-up.[3] Dopplers should be ordered for suspected carotid stenosis before ordering more advanced radiological studies, but may not be helpful in non-carotid arterial causes. In general, both CT and MRI are complementary imaging modalities to identify vascular etiologies of pulsatile tinnitus. Suspected arterial etiologies not well defined by duplex should get a CTA. CTA may also identify aneurysms, which may manifest as pulsatile tinnitus. MRV better evaluates venous etiology. It is appropriate to get a CT of the temporal bones if there is clinical suspicion for temporal bone pathology. Patients with focal nerve deficits are candidates for brain imaging, either CT or MRI, to evaluate for more serious causes of pulsatile tinnitus.[9][3] Other conditions may require further evaluation by specialists such as IIH, which can be diagnosed by normal brain CT/MRI and increased opening pressure on lumbar puncture. Performing an optic exam on these patients may reveal papilledema.

Treatment / Management

Up to 70% of patients will have an identifiable cause of their pulsatile tinnitus, which will direct patient management.[3] Treatment will largely be guided by the specific pathophysiology of each patient. Therapeutic interventions may include a wide variety of medical professionals working together to coordinate care. Treatment can range from observation to medical management and surgery.[4][10] Some treatments for tinnitus, such as decreasing caffeine intake, cognitive behavior therapy, tinnitus retraining therapy, and sound therapy, may be offered to patients, but there are no studies regarding their efficacy specifically in pulsatile tinnitus patients.[11](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential for pulsatile tinnitus is very broad and can be overwhelming. It is essential first to try and determine if the tinnitus is vascular or non-vascular. Vascular lesions require further categorization into arterial vs. venous etiology. Figure 1 has a helpful flowchart that includes an extensive list of potential etiologies. Using this progression will help direct management and care for the majority of patients presenting with pulsatile tinnitus.

Common conditions include:

- Arteriovenous fistula

- Atherosclerotic vascular stenosis

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

- Anomalous basilar artery

- Paraganglioma

- Tensor tympani myoclous

- Paget Disease

- Otosclerosis

Prognosis

The prognosis for pulsatile tinnitus varies considerably based on the etiology. Pulsatile tinnitus due to extensive cardiovascular disease may have a detrimental impact on patient morbidity and mortality. However, other causes may have no serious long-term effects on the patient. It is also possible that patients will have a resolution of their symptoms following treatment of the underlying cause. Early detection and treatment are the optimal means to improve patient outcomes.

Complications

Complications from pulsatile tinnitus will vary based on the etiology. Some pathology will be benign to the patient; however, the patient’s tinnitus may be a symptom of a much more serious disease. Morbidity is possible both from the pathophysiology itself and as a result of attempting to treat the patient with invasive modalities such as surgery and radiation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is essential to allow the patient to partake in their treatment plan, achieved by keeping them informed about their diagnosis. Despite the wide variety of etiologies for pulsatile tinnitus, it is vital that patients understand their disease process. One such example would be patients with carotid bruits. This group of patients should receive counsel on ways to improve their cardiovascular health and the importance of following up regularly with their primary care team. It is also important to reassure patients with idiopathic pulsatile tinnitus that there is no significant identifiable pathology. Some patients can tolerate their symptoms as long as they receive reassurance that they do not have serious pathology.[4]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with pulsatile tinnitus can present in many different clinical environments. Health practitioners in primary care need to know when it is appropriate to refer patients to an otolaryngologist. In the otolaryngology office, the physician will work closely with the audiologist to help begin the work-up on the patient. Otolaryngology specialty trained nurses play a crucial role as they will help coordinate future appointments and imaging studies that may be necessary. They will also assist in educating the patient and family regarding the condition and any medications they try. After a thorough workup, the otolaryngologist needs to begin constructing a treatment team based on the suspected etiology of the patient’s symptoms. This team may include practitioners from radiology, neurosurgery, cardiology, otolaryngology nurses, and the primary care team. If surgery becomes a treatment modality, the health-care team will grow immensely to include nurses, surgical technicians, pharmacists, and physical therapists. These health care professionals will all play a vital role in providing patients with quality care, and a team approach will produce the best outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hofmann E, Behr R, Neumann-Haefelin T, Schwager K. Pulsatile tinnitus: imaging and differential diagnosis. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2013 Jun:110(26):451-8. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0451. Epub 2013 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 23885280]

Levine RA, Oron Y. Tinnitus. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2015:129():409-31. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00023-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25726282]

Pegge SAH, Steens SCA, Kunst HPM, Meijer FJA. Pulsatile Tinnitus: Differential Diagnosis and Radiological Work-Up. Current radiology reports. 2017:5(1):5. doi: 10.1007/s40134-017-0199-7. Epub 2017 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 28203490]

Sismanis A, Pulsatile tinnitus: contemporary assessment and management. Current opinion in otolaryngology [PubMed PMID: 22552697]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVillaça Avoglio JL. Dental occlusion as one cause of tinnitus. Medical hypotheses. 2019 Sep:130():109280. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.109280. Epub 2019 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 31383322]

Keidar E, De Jong R, Kwartowitz G. Tensor Tympani Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085597]

McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Somerset S, Hall D. A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hearing research. 2016 Jul:337():70-9. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.009. Epub 2016 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 27246985]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWu V, Cooke B, Eitutis S, Simpson MTW, Beyea JA. Approach to tinnitus management. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2018 Jul:64(7):491-495 [PubMed PMID: 30002023]

Esmaili AA,Renton J, A review of tinnitus Australian journal of general practice. 2018 Apr [PubMed PMID: 29621860]

Venous sinus stenting for idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis., Nicholson P,Brinjikji W,Radovanovic I,Hilditch CA,Tsang ACO,Krings T,Mendes Pereira V,Lenck S,, Journal of neurointerventional surgery, 2018 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 30166333]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLangguth B. Treatment of tinnitus. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2015 Oct:23(5):361-8. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000185. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26261868]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence