Introduction

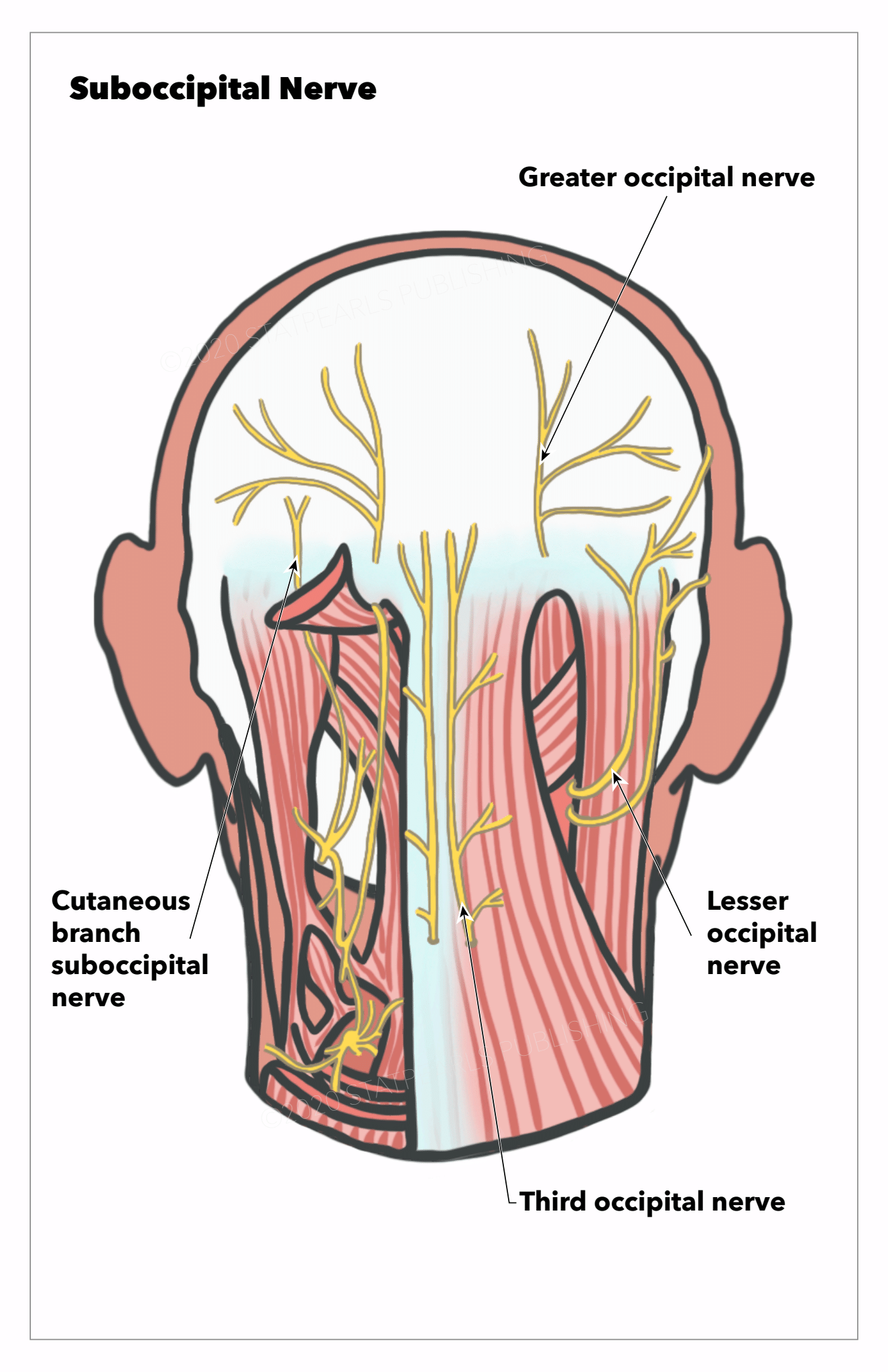

The suboccipital nerve, also known as the dorsal ramus of the 1st cervical nerve, arises from the C1 posterior ramus (see Image. Nerves of the Posterior Head and Neck Region).[1] This nerve lies within the suboccipital triangle, a region at the neck's superoposterior aspect. Thus, the suboccipital nerve is intimately related to the craniocervical junction and important structures in this area.

The suboccipital nerve innervates the suboccipital muscles, which play an important role in cervicogenic neck pain and headaches. Novel headache pharmacological treatments thus target this nerve.[2][3] Additionally, Surgical procedures involving the craniocervical junction and occipital area can injure the suboccipital nerve. Understanding the anatomic relationships of this important structure is essential to managing various head and neck conditions.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The suboccipital nerve forms from ventral and dorsal rootlets emerging from the spinal cord and uniting within the subarachnoid space. The C1 dorsal rootlets are often fewer in number than their ventral counterparts and may even be absent in approximately 40% of individuals. This feature contrasts with other cervical spinal nerves, which have more dorsal than ventral rootlets.

The dorsal roots contributing to the suboccipital nerve form a dorsal root ganglion with an average diameter of 7 mm in approximately 30% of people. From the subarachnoid space, the C1 spinal nerve travels about 11 mm before exiting the dura mater and splitting into ventral and dorsal rami.

The suboccipital nerve is so-called because it innervates the suboccipital muscles exclusively. The nerve has no cutaneous, meningeal, or articular branches.[4] After splitting from the ventral ramus, the suboccipital nerve travels an average of 12 mm before innervating the suboccipital muscles.

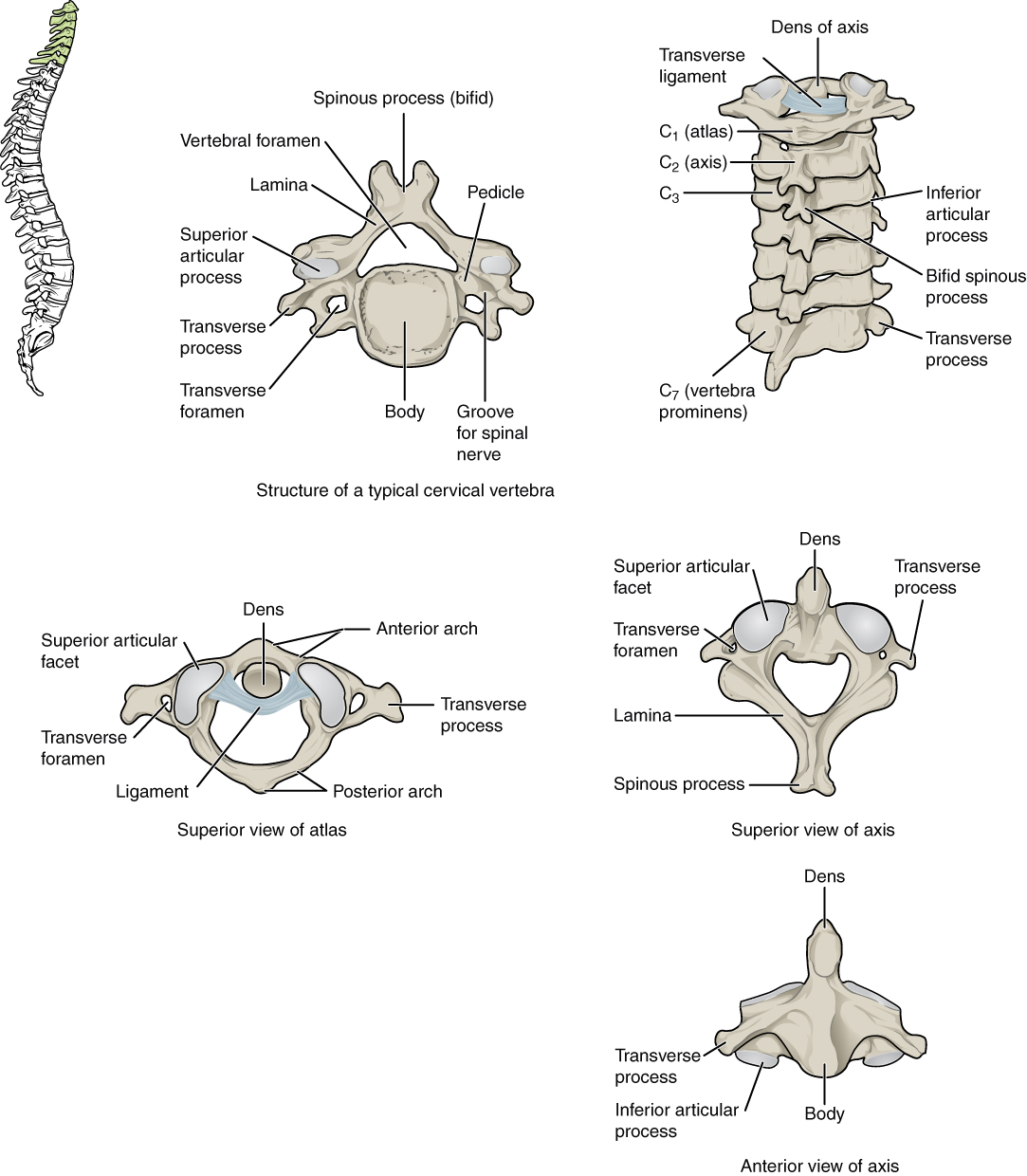

The suboccipital nerve is intimately related to the C1 vertebra (atlas) and vertebral artery (see Image. Cervical Vertebrae). The vertebral artery is divided anatomically into 4 parts, 3 extradural and a final intradural segment, before becoming the basilar artery (see Image. Vertebral Artery Anatomy in the Neck Region). The vertebral artery's 3rd segment (V3) is often termed the ‘atlantic’ segment because it travels within a groove over the atlas' posterior arch.[5] The suboccipital nerve lies between the atlas' posterior arch and the vertebral artery is demonstrable in cadaveric specimens.

The suboccipital nerve and V3 arterial segment lie within the suboccipital triangle, which is bounded by some of the muscles the suboccipital nerve innervates. The suboccipital triangle's borders are the rectus capitis posterior major medially, obliquus capitis superior superolaterally, and obliquus capitis inferior inferolaterally. The suboccipital triangle's apex faces inferomedially at the bifid spinous process of the C2 vertebra (axis).

The suboccipital nerve innervates the 3 muscles bordering the suboccipital triangle and the rectus capitis posterior minor. Collectively, the suboccipital muscles function as the head's postural muscles, assisting in head extension and rotation. The suboccipital muscles turn the head by rotating the atlas and axis.[6][7]

The suboccipital nerve may also fuse with the C2 and C3 dorsal rami as part of the Cruveilhier plexus.[8] Cadaveric studies have demonstrated significant individual variations in the connections between the Cruveilhier plexus' nerves.

Embryology

The suboccipital nerve emerges from the paraxial and visceral mesoderm interactions at a zone called the "head-neck interface." These interactions give rise to cranial nerves X, XI, XII, and cervical nerves 1 to 6. Embryological studies indicate that C1 develops primarily from somitomeres that undergo segmentation and resegmentation during embryonic development. Variability in these processes likely contributes to the anatomical variations seen in the suboccipital nerve.[9][10]

Muscles

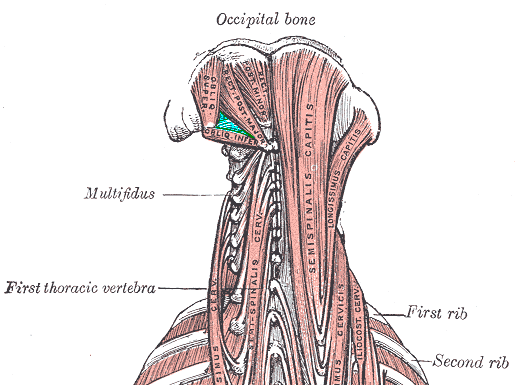

The suboccipital nerve innervates 4 muscles: the rectus capitis posterior major, rectus capitis posterior minor, obliquus capitis superior, and obliquus capitis inferior. These muscles create a functional unit that assists in precise head movements and contributes to posture maintenance (see Image. Deep Posterior Neck Muscles).

The rectus capitis posterior major forms the suboccipital triangle's medial edge. This muscle originates from the C2 vertebra's bifid spinous process before extending superolaterally and inserting immediately below the occipital bone's nuchal line. The rectus capitis posterior major is a head extensor and ipsilateral rotator of the head and atlas.[11]

The rectus capitis posterior minor lies outside the suboccipital triangle, between the rectus capitis posterior major and the midline. This muscle arises from the atlas' posterior arch. The rectus capitis posterior minor courses superiorly before inserting below the nuchal line medial to the rectus capitis posterior major's insertion. This muscle is a weak head extensor.

The obliquus capitis superior forms the superolateral border of the suboccipital triangle. This muscle originates from the transverse atlas' process and fans out superiorly, inserting on the occipital bone between the superior and inferior nuchal lines. The obliquus capitis superior is a lateral head flexor.

The obliquus capitis inferior forms the suboccipital triangle's inferolateral margin. This muscle originates inferior to the rectus capitis posterior major's origin on the axis' bifid spine and traverses superomedially. The obliquus capitis inferior then inserts on the atlas' transverse process medial to the obliquus capitis superior's origin. This muscle rotates the atlas ipsilaterally.[12][13]

Physiologic Variants

Cadaveric studies report individual variations involving the origins of the C1 spinal nerve and, consequently, the suboccipital nerve. A study of 80 cadaveric specimens found that the dorsal rootlets were present alongside the ventral rootlets in 60% of cases and formed a dorsal root ganglion in 30% of cases. Conversely, around 40% of specimens had no dorsal rootlets contributing to the C1 spinal nerve. In a separate study of 13 cadaveric specimens, the suboccipital nerve emerged from the C1 ventral ramus and fused with the C2 dorsal ramus. However, these interindividual differences do not affect the suboccipital nerve's function or relationships to the suboccipital muscles.

Surgical Considerations

Suboccipital nerve injury may result from surgical procedures of the posterior neck at the C1 and C2 levels. A midline suboccipital approach, as in a distal vertebral artery bypass or procedures accessing the brain's fourth ventricle, and posterior approaches for cervical neck fusions may also damage the suboccipital nerve.[14]

Clinical Significance

The suboccipital nerve may play a role in the pathogenesis of cervicogenic headaches and occipital neuralgia. The nerve may also be vulnerable to trauma from whiplash injuries. The suboccipital nerve is thus a potential pharmacological target for treating head-and-neck pain syndromes.

Occipital Neuralgia and Cervicogenic Headaches

Occipital neuralgia, also called "C2 neuralgia," is a condition presenting with recurrent occipital headaches associated with suboccipital pain. The pain develops suddenly across the greater and lesser occipital nerves' dermatomes, often unilaterally. The condition is thought to be due to external compression and subsequent irritation of the greater and lesser occipital nerves.

Patients describe the sensation as a brief shooting, lightning-like, or stabbing-like pain in the occipital area. The symptom may be precipitated by pressure to the occipital region, specific head-and-neck movements, excessively contracted neck muscles, cervical spondylosis, or cervical fractures.[15] The suboccipital nerve's anatomic variations may play a role in the pathogenesis of occipital neuralgia. Variations involving attachments between the suboccipital and greater and lesser occipital nerves have been implicated.[16]

Cervicogenic headaches present as unilateral headaches brought on by cervical vertebral movement or compression. The pain primarily originates from the posterior neck area and is referred anywhere to the scalp. Cervicogenic headaches are thought to be due to cervical vertebral pathology expanding to the C1 to C3 nerves. The suboccipital nerve may contribute to cervicogenic headaches, especially in certain anatomic variants where it connects with the greater and lesser occipital nerves.[17][18] Occipital nerve blocks may be therapeutic and often diagnostic of occipital neuralgia and cervicogenic headaches.[19][20]

Cluster Headaches

Cluster headaches are characterized by attacks of severe unilateral pain prominently around the orbital, supraorbital, or temporal area.[21] The headaches may be associated with rhinorrhea, tearing, and sweating. The pain's severity can limit a patient's function.

Steroid or local anesthetic injections on the greater occipital nerve area have been used to treat cluster headaches.[22] A high-volume suboccipital nerve block with local anesthetic has been found to be beneficial to a small group of patients with cluster headaches refractory to other medical treatments. An average response time of 10.3 weeks was reported among responders, with 2 patients achieving pain freedom for 44 weeks. The intervention was found to be safe and well-tolerated. However, larger studies are necessary to support this procedure's value in this patient cohort.[23]

Postdural Puncture Headache

Spinal anesthesia can cause postdural puncture headaches. The condition presents similarly to postural headaches and may be associated with neck stiffness and, rarely, photophobia, tinnitus, or vomiting.[24] The incidence of postdural puncture headaches is approximately 25% but may vary with body mass index and the technique and number of attempts required to establish spinal anesthesia.[25]

The management of postdural puncture headaches has been a topic of debate. Current practice favors placing an epidural blood patch to seal hypothetical CSF leaks following spinal punctures.[26] Meanwhile, a randomized control trial involving women who underwent spinal anesthesia during a Caesarian section found that bilaterally injecting dexamethasone in the suboccipital muscles reduced postdural puncture headache scores. Reliance on oral analgesia and nausea were also reported to be less after the combined steroid-anesthetic injection.[27]

Suboccipital Muscle Spasm

The suboccipital muscles can become strained like other muscles, resulting in neck pain, spasms, or headaches. A possible cause of suboccipital muscle strain is a whiplash injury, which arises from rapid deceleration of the body with respect to the head and neck. Damage to the suboccipital nerve from such a mechanism may be due to rectus capitis posterior minor injury.[28] Suboccipital muscle strain management is generally supportive and includes posture correction, massage, stretching, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug intake, yoga, acupuncture, and physical therapy.[29][30][31]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Deep Posterior Neck Muscles. This illustration shows the muscles bordering the suboccipital triangle: the rectus capitis posterior major (medial), obliquus capitis superior (superolateral), and obliquus capitis inferior (inferolateral). Other muscles in this image include the rectus capitis posterior minor, multifidus, semispinalis capitis and cervicis, longissimus capitis and cervicis, and iliocostalis cervicis. Labeled bony structures include the 1st thoracic vertebra and first and second ribs.

Medical Gallery of Mikael Häggström 2014, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Cervical Vertebrae. A. Superior view of a typical cervical vertebra. B. Posterior view of the cervical spine. C. Superior view of C1 articulating with the dens. D. Superior view of C2. E. Anterior view of C2.

Contributed by Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions (http://cnx.org/content/col11496/1.6/, Jun 19, 2013)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jenkins S, Iwanaga J, Dumont AS, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. What is the suboccipital nerve? Tracking this confusing historical nomenclature. Morphologie : bulletin de l'Association des anatomistes. 2021 Feb:105(348):10-14. doi: 10.1016/j.morpho.2020.09.002. Epub 2020 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 33172783]

Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Slappey JB, Shoja MM, Oakes WJ, Salter EG. Clinical anatomy of the C1 dorsal root, ganglion, and ramus: a review and anatomical study. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2007 Aug:20(6):624-7 [PubMed PMID: 17330847]

Gutierrez S, Huynh T, Iwanaga J, Dumont AS, Bui CJ, Tubbs RS. A Review of the History, Anatomy, and Development of the C1 Spinal Nerve. World neurosurgery. 2020 Mar:135():352-356. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.12.024. Epub 2019 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 31838236]

Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Yalçin B, Shoja MM, Cohen-Gadol AA. Classification and clinical anatomy of the first spinal nerve: surgical implications. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2009 Apr:10(4):390-4. doi: 10.3171/2008.12.SPINE08661. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19441999]

Giotta Lucifero A, Baldoncini M, Bruno N, Tartaglia N, Ambrosi A, Marseglia GL, Galzio R, Campero A, Hernesniemi J, Luzzi S. Microsurgical Neurovascular Anatomy of the Brain: The Posterior Circulation (Part II). Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis. 2021 Aug 26:92(S4):e2021413. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92iS4.12119. Epub 2021 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 34437362]

Lake S, Iwanaga J, Oskouian RJ, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. A Case Report of an Enlarged Suboccipital Nerve with Cutaneous Branch. Cureus. 2018 Jul 6:10(7):e2933. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2933. Epub 2018 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 30202665]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBogduk N. Functional anatomy of the spine. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2016:136():675-88. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53486-6.00032-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27430435]

Tubbs RS, Mortazavi MM, Loukas M, D'Antoni AV, Shoja MM, Cohen-Gadol AA. Cruveilhier plexus: an anatomical study and a potential cause of failed treatments for occipital neuralgia and muscular and facet denervation procedures. Journal of neurosurgery. 2011 Nov:115(5):929-33. doi: 10.3171/2011.5.JNS102058. Epub 2011 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 21682566]

Offiah CE, Day E. The craniocervical junction: embryology, anatomy, biomechanics and imaging in blunt trauma. Insights into imaging. 2017 Feb:8(1):29-47. doi: 10.1007/s13244-016-0530-5. Epub 2016 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 27815845]

Hovorka MS, Uray NJ. Microscopic clusters of sensory neurons in C1 spinal nerve roots and in the C1 level of the spinal accessory nerve in adult humans. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2013 Oct:296(10):1588-93. doi: 10.1002/ar.22757. Epub 2013 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 23929774]

Torun Bİ, Kendir S, Filgueira L, Shane Tubbs R, Uz A. Morphological characteristics of the posterior neck muscles and anatomical landmarks for botulinum toxin injections. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2021 Aug:43(8):1235-1242. doi: 10.1007/s00276-021-02745-2. Epub 2021 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 33847773]

Scherer SS, Schiraldi L, Sapino G, Cambiaso-Daniel J, Gualdi A, Peled ZM, Hagan R, Pietramaggiori G. The Greater Occipital Nerve and Obliquus Capitis Inferior Muscle: Anatomical Interactions and Implications for Occipital Pain Syndromes. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2019 Sep:144(3):730-736. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005945. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31461039]

Takebe K, Vitti M, Basmajian JV. The functions of semispinalis capitis and splenius capitis muscles: an electromyographic study. The Anatomical record. 1974 Aug:179(4):477-80 [PubMed PMID: 4842939]

Choque-Velasquez J, Hernesniemi J. One burr-hole craniotomy: Suboccipital midline approach to the fourth ventricle in Helsinki neurosurgery. Surgical neurology international. 2018:9():170. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_194_18. Epub 2018 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 30210903]

Choi I, Jeon SR. Neuralgias of the Head: Occipital Neuralgia. Journal of Korean medical science. 2016 Apr:31(4):479-88. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.4.479. Epub 2016 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 27051229]

Cesmebasi A, Muhleman MA, Hulsberg P, Gielecki J, Matusz P, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. Occipital neuralgia: anatomic considerations. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2015 Jan:28(1):101-8. doi: 10.1002/ca.22468. Epub 2014 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 25244129]

Bogduk N. The anatomical basis for cervicogenic headache. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 1992 Jan:15(1):67-70 [PubMed PMID: 1740655]

Bogduk N, Govind J. Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet. Neurology. 2009 Oct:8(10):959-68. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70209-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19747657]

Grgić V. [Cervicogenic headache: etiopathogenesis, characteristics, diagnosis, differential diagnosis and therapy]. Lijecnicki vjesnik. 2007 Jun-Jul:129(6-7):230-6 [PubMed PMID: 18018715]

Baek IC, Park K, Kim TL, O J, Yang HM, Kim SH. Comparing the injectate spread and nerve involvement between different injectate volumes for ultrasound-guided greater occipital nerve block at the C2 level: a cadaveric evaluation. Journal of pain research. 2018:11():2033-2038 [PubMed PMID: 30310307]

Ljubisavljevic S, Zidverc Trajkovic J. Cluster headache: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Journal of neurology. 2019 May:266(5):1059-1066. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9007-4. Epub 2018 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 30120560]

Lambru G, Abu Bakar N, Stahlhut L, McCulloch S, Miller S, Shanahan P, Matharu MS. Greater occipital nerve blocks in chronic cluster headache: a prospective open-label study. European journal of neurology. 2014 Feb:21(2):338-43. doi: 10.1111/ene.12321. Epub 2013 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 24313966]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRozen TD. High-Volume Anesthetic Suboccipital Nerve Blocks for Treatment Refractory Chronic Cluster Headache With Long-Term Efficacy Data: An Observational Case Series Study. Headache. 2019 Jan:59(1):56-62. doi: 10.1111/head.13394. Epub 2018 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 30144049]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceThew M, Paech MJ. Management of postdural puncture headache in the obstetric patient. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2008 Jun:21(3):288-92. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3282f8e21a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18458543]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGirma T, Mergia G, Tadesse M, Assen S. Incidence and associated factors of post dural puncture headache in cesarean section done under spinal anesthesia 2021 institutional based prospective single-armed cohort study. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2022 Jun:78():103729. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103729. Epub 2022 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 35600186]

Malhotra S. All patients with a postdural puncture headache should receive an epidural blood patch. International journal of obstetric anesthesia. 2014 May:23(2):168-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2014.01.001. Epub 2014 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 24656528]

Abdelraouf M, Salah M, Waheb M, Elshall A. Suboccipital Muscles Injection for Management of Post-Dural Puncture Headache After Cesarean Delivery: A Randomized-Controlled Trial. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences. 2019 Feb 28:7(4):549-552. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.105. Epub 2019 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 30894910]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHack GD, Koritzer RT, Robinson WL, Hallgren RC, Greenman PE. Anatomic relation between the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle and the dura mater. Spine. 1995 Dec 1:20(23):2484-6 [PubMed PMID: 8610241]

Taylor JR, Finch PM. Neck sprain. Australian family physician. 1993 Sep:22(9):1623-5, 1627, 1629 [PubMed PMID: 8240126]

Moraska AF, Schmiege SJ, Mann JD, Butryn N, Krutsch JP. Responsiveness of Myofascial Trigger Points to Single and Multiple Trigger Point Release Massages: A Randomized, Placebo Controlled Trial. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2017 Sep:96(9):639-645. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000728. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28248690]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCohen SP. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of neck pain. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2015 Feb:90(2):284-99. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.09.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25659245]