Introduction

The thyroid gland is a midline structure located in the anterior neck. The thyroid functions as an endocrine gland and is responsible for producing thyroid hormone and calcitonin, thus contributing to the regulation of metabolism, growth, and serum concentrations of electrolytes such as calcium.[1][2]

Many disease processes can involve the thyroid gland, and alterations in the production of hormones can result in hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. The thyroid gland is involved in inflammatory processes (e.g., thyroiditis), autoimmune processes (e.g., Graves disease), and cancers (e.g., papillary thyroid carcinoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, and follicular carcinoma).

In addition to considering its role in metabolism, growth, regulation of certain electrolytes, and its involvement in many disease processes, the thyroid gland deserves consideration for its anatomical location and its close relationship to important structures, including the parathyroid glands, recurrent laryngeal nerves, and certain vasculature.

Anatomy Overview

The thyroid gland is divided into two lobes connected by the isthmus, which crosses the midline of the upper trachea at the second and third tracheal rings. In its anatomic position, the thyroid gland lies posterior to the sternothyroid and sternohyoid muscles, wrapping around the cricoid cartilage and tracheal rings. It is located inferior to the laryngeal thyroid cartilage, typically corresponding to the vertebral levels C5-T1. The thyroid attaches to the trachea via a consolidation of connective tissue, referred to as the lateral suspensory ligament or Berry’s ligament. This ligament connects each of the thyroid lobes to the trachea. The thyroid gland, along with the esophagus, pharynx, and trachea, is found within the visceral compartment of the neck, which is bound by pretracheal fascia.

The “normal” thyroid gland has lateral lobes that are symmetrical with a well-marked centrally located isthmus. The thyroid gland typically contains a pyramidal extension on the posterior-most aspect of each lobe, referred to as the tubercle of Zuckerkandl. Despite these general characteristics, the thyroid gland is known to have many morphologic variations. The position of the thyroid gland and its close relationship with various structures brings about several surgical considerations with clinical relevance.

Embryology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Embryology

The parenchyma of the thyroid gland is derived from endoderm. The thyroid gland originates from the foramen cecum, which is a pit positioned at the posterior one-third of the tongue. Early in gestation, the thyroid gland begins its descent anterior to the pharynx as a bilobed diverticulum. The thyroid gland then continues to descend anterior of the hyoid bone and the cartilages of the larynx. By the seventh week, the thyroid gland reaches its destination midline and anterior to the upper trachea. The thyroglossal duct maintains the connection of the thyroid gland to the base of the tongue until the involution and disappearance of the duct.

The ultimobranchial body, derived from the ventral region of the fourth pharyngeal pouch, then becomes incorporated into the dorsal aspect of the thyroid gland. The ultimobranchial body gives rise to the parafollicular cells or C cells of the thyroid gland.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The thyroid gland has an extremely rich blood supply and is estimated to be six times as vascular as the kidney and relatively three to four times more vascular than the brain. It receives blood from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries. These paired vessels supply the superior and inferior aspects of the gland. The superior thyroid artery is the first branch of the external carotid artery as it arises near the level of the superior horn of the thyroid cartilage. The superior thyroid artery then moves anterior, inferior, and towards the midline behind the sternothyroid muscle to the superior pole of the lobe of the thyroid gland. From this point, the superior thyroid artery branches off. One branching point runs down the dorsal aspect of the thyroid gland. The other superficial branch runs along the sternothyroid muscle and thyrohyoid muscles, supplying branches to these muscles as well as the sternohyoid. The superficial branch continues downward to further give off the cricothyroid branch and to supply the isthmus, inner sides of the lateral lobes, and, when present, the pyramidal lobe.[3]

The thyrocervical trunk arises from the anterosuperior surface of the subclavian artery and gives rise to three branches, one being the inferior thyroid artery. The inferior thyroid artery branches from the thyrocervical trunk at the inner border of the anterior scalene muscle and advances medially to the thyroid gland. The artery reaches the posterior surface of the lateral lobe of the thyroid gland at the level of the junction of the upper two-thirds and lower third of the outer border. The largest branch of the inferior thyroid artery is the ascending cervical branch, and it is important not to mistake this branch for the inferior thyroid artery itself.[4]

In 10% of the population, there is an additional artery known as the thyroid ima artery. This artery has a variable origin, including the brachiocephalic trunk, aortic arch, the right common carotid, the subclavian, the pericardiacophrenic artery, the thyrocervical trunk, transverse scapular, or internal thoracic artery. The thyroid ima most commonly originates from the brachiocephalic trunk and supplies the isthmus and anterior thyroid gland.

The thyroid gland is drained via the superior, middle, and inferior thyroid veins. The middle and superior thyroid veins follow a tortuous route and eventually drain into the internal jugular vein on either side of the neck. The drainage of the inferior thyroid vein may enter either the subclavian or brachiocephalic veins, located just posterior to the manubrium.

Lymphatic drainage of the thyroid gland involves the lower deep cervical, prelaryngeal, pretracheal, and paratracheal nodes. The paratracheal and lower deep cervical nodes, specifically, receive lymphatic drainage from the isthmus and the inferior lateral lobes. The superior portions of the thyroid gland drain into the superior pretracheal and cervical nodes.

Nerves

The autonomic nervous system primarily innervates the thyroid gland. The vagus nerve provides the main parasympathetic fibers, while sympathetic fibers originate from the inferior, middle, and superior ganglia of the sympathetic trunk. The autonomic nervous system does not play a role in the control of hormonal production or secretion but mostly influences vasculature.[4]

Muscles

Several muscles should be considered when discussing neck and thyroid surgical anatomy.

- Platysma: The first muscle encountered during neck dissection, it is enveloped by the superficial cervical fascia. It sits in the anterior neck and extends from the superficial fascia of the deltoid over the clavicle, reaching the mandible and superficial fascia of the face superiorly.

- Sternocleidomastoid: This muscle forms the anterior portion of the posterior triangle of the neck. The muscle runs obliquely from the mastoid to the clavicle and sternum. The sternocleidomastoid is found anterolaterally relative to the thyroid gland.

- Digastric muscle: This muscle extends from the mandibular tubercle, passes deep and inferior to the hyoid, and loops back up to attach to the mastoid tip.

- Infrahyoid muscles: These are also referred to as “strap muscles.” They include four paired muscles on the anterolateral surface of the thyroid gland. The strap muscles result in gross movement of the larynx during swallowing and also adjust the positioning of the larynx during vocalization.

- Omohyoid muscle: The omohyoid muscle is found deep in the sternocleidomastoid. It extends from the hyoid bone to the lateral aspect of the clavicle.

- Sternohyoid muscle: This muscle sits anterior to the remaining strap muscles and the thyroid gland. The sternohyoid muscle extends from its superior attachment at the hyoid bone inferiorly to the sternum.

- Sternothyroid muscle: This muscle extends from the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage to the sternum. This muscle contacts the anterior surface of the thyroid gland.

- Thyrohyoid muscle: The thyrohyoid muscle extends from the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage to the hyoid bone superiorly.

- Inferior pharyngeal constrictor: This muscle extends from its anterior attachment at the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage and lateral aspect of the cricoid cartilage to the pharyngeal raphe. This muscle contacts the superior pole of the lateral lobe of the thyroid gland medially.

Physiologic Variants

Ectopic thyroid tissue can be found anywhere along the migratory pathway and has been documented in locations ranging from the tongue to the diaphragm. The prevalence of an ectopic thyroid gland is between 1 per 100,000 and 1 per 300,000. The most common site for ectopic thyroid tissue is the ectopic lingual thyroid at the base of the tongue.[5]

The thyroid gland may have a pyramidal lobe that extends superiorly from the isthmus. The pyramidal lobe is a normal vestigial remnant of the thyroglossal duct. This has been documented to occur in 28% to 55% of individuals. Most commonly, the pyramidal lobe will originate on the left side of the thyroid. The pyramidal lobe can be separated entirely from the main thyroid gland and has also been documented to occur bilaterally.

In addition to a pyramidal lobe, a wide variety of morphologic variations exist. The isthmus may be large, narrowed, or entirely absent. The lateral lobes may vary in size and symmetry when comparing right to left.

Surgical Considerations

Due to its close relationship with several structures, the following must be considered during total thyroidectomy, thyroid lobectomy, or procedures involving the excision of a thyroglossal duct cyst.[6][7][4]

- Chest radiography or mediastinal computed tomography [CT] is performed preoperatively if anatomic abnormalities or substernal extension of the thyroid are suspected.

- Due to the location of the thyroid gland, slight neck extension of the patient on the operating table facilitates access to the neck.

- The typical skin incision allowing proper access to the gland ranges from one to one and a half to two fingerbreadths above the clavicle. This incision is curvilinear and parallel or within a skin line.

Larynx

In re-operative cases, it is recommended to perform laryngoscopy regardless of voice symptomology. Asymptomatic vocal cord paralysis can occur in up to 30% of patients after anterior neck surgery.

Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve

The two nerves of importance that pass through the thyroid are the left and right recurrent laryngeal nerves [RLN]. They are often located on the lateral aspect of the thyroid gland near the vicinity of the inferior thyroid artery. When operating on the thyroid gland, it is vital to visualize these nerves and avoid trauma. The nerve can be exposed caudal to the inferior thyroid artery or following mobilization of the superior and inferior poles. The nerve is most likely to be injured in its distal portion [2-3cm]. This distal portion of the RLN is covered by either or both the tubercle of Zuckerkandl [a pyramidal extension on the most posterior aspect of each lobe] and the ligament of Berry. Most often, it is not until the tubercle of Zuckerkandl is medially retracted that the RLN is seen. The RLN most often traverses just medial to the tubercle and is hidden from view. The distal course of the RLN is more easily identified in total lobectomies as opposed to subtotal lobectomies, in which the distal course of the RLN may not always be visualized.

Another surgical consideration is the anatomic variation of the nerves. In approximately 1% of cases, a nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve or direct vagus branch is identified on the right side following retraction of the tubercle of Zuckerkandl.

Also, due to variations in which the RLN can bifurcate or trifurcate proximal to its laryngeal entrance, it is imperative to ensure that no nerve branch within the ligament of Berry is cut or clamped.

Lastly, it is important to note that the potential for nerve injury can occur from direct injury to the nerve or indirectly from heat from the use of electrocautery in close proximity to the nerves.

Superior Laryngeal Nerve

When the superior pole of the thyroid gland is dissected, one may visualize the superior laryngeal nerve [SLN], which often runs next to the superior thyroid artery. High ligation of the superior thyroid artery should be avoided as one can easily injure the superior laryngeal nerve. Approximately 20% of patients are at risk of injury to the external branch of the SLN when using a technique in which the superior thyroid vessels are clamped, divided, and ligated en masse. Dividing the superior thyroid vessels as they enter the capsule prevents injury to those nerves in close proximity to the artery. Most surgeons do not insist on direct visualization of the superior laryngeal nerve.

In addition to direct damage from clamping, imprudent use of electrocautery brings about the potential for paresis. Due to the potential for heat damage, electrocautery should never be used to correct bleeding in the region of the cricothyroid muscle or inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle. Bipolar cautery should still warrant caution. Lastly, the anterior suspensory ligament may be adherent to the cricothyroid muscle. Thus, one should be cautious of direct damage to the cricothyroid muscle while dissecting the anterior suspensory ligament.

Cervical Sympathetic Trunk

Rarely, the cervical sympathetic trunk may be injured. This is a consideration when the carotid sheath is mobilized to treat retroesophageal extension of a goiter or malignancy.

Esophagus

Altered anatomy and displacement of the trachea can result in the exposure of the anterior esophageal surface, creating the risk of potential injury.

Carotid artery:

The carotid arteries, which course posterolateral to the thyroid gland, are rarely an issue during thyroidectomy. Excessive lateral traction in an individual with an enlarged thyroid gland may result in ocular or central nervous system damage from reduced blood flow. This is preventable with proper retraction and tissue handling.

Parathyroid Glands

The parathyroid glands are in close anatomic relationship to the thyroid gland, sitting on the posterior aspect of the thyroid gland. The parathyroid glands also share arterial supply with the thyroid gland, being supplied by an end-artery, typically the inferior thyroid artery. Due to its anatomic relationship and vascular supply, there are a few considerations with regard to the parathyroid glands in thyroid surgeries.

By dividing the branches of the inferior thyroid artery beyond the parathyroid gland on the thyroid gland capsule, disruption of the end-artery can best be avoided. However, transplantation to a “dry” pocket in the sternocleidomastoid muscle, a subcutaneous area, or forearm can be performed if end-artery damage does occur.

Inadvertent removal of one or more of the parathyroid glands can occur during thyroidectomy, and inspection of the resected tissue should be considered to identify these glands and transplant them. With regards to total thyroidectomy, one study documented that zero out of 100 patients suffered from permanent hypoparathyroidism following the transplant of at least one parathyroid gland. A second study documented an occurrence of 21.4% transient hypocalcemia and 0% occurrence of permanent hypocalcemia following transplant of at least one parathyroid gland during total thyroidectomy.

Standard preoperative labs should include a serum calcium assay. It is also important to determine if a patient is normocalcemic postoperatively. Hypocalcemic patients should be treated with calcium and vitamin D as appropriate. Careful monitoring of calcium levels should continue in the weeks following discharge.

Thyroglossal Duct Cyst Procedure

Approximately 50% of thyroglossal duct cysts are close to or just inferior to the hyoid bone. Due to its relation to the hyoid bone and the rates of recurrence, surgical removal includes the cyst, the middle segment of the hyoid bone, and the tract that leads to the base of the tongue. This procedure is referred to as the Sistrunk Procedure.

Postoperative Bleeding

Due to the location, hematomas may lead to acute respiratory problems. Insidious hemorrhage may also result in laryngeal edema and infrequently can lead to the need for tracheostomy.

Muscle Closure Following Thyroid Procedures

Surgical considerations for wound closure are under consideration of transversely divided muscles. One must consider a closure that would create space for blood to disperse if bleeding were to occur.

When the strap muscles are separated from the midline and retracted laterally, reapproximation in the midline is performed, once again, with consideration of space for possible bleeding. Additionally, some reapproximate the platysma muscle and its fascia.

Clinical Significance

Diseases and anomalies of the thyroid gland and subsequent surgeries can result in various presentations and complications that bear clinical significance.[8]

Consequences of Ectopic Thyroid Tissue

Ectopic thyroid tissue can present with varying symptomatology depending on its location. Lingual ectopic thyroid tissue may present with dysphagia, bleeding, and dyspnea. Suprahyoid and infrahyoid thyroid tissue may present as a midline mass in the neck, similar to a thyroglossal duct cyst. Intratracheal or intralaryngeal thyroid tissue may present as a respiratory obstruction. Intraesophageal thyroid tissue may present as dysphagia. Typically, the presence of a pyramidal lobe is asymptomatic. Likewise, aortic, pericardial, and cardiac thyroid tissue are also asymptomatic.

Surgical Consequences

Various nerves are at potential risk for injury during thyroidectomies and other thyroid related surgeries, including the recurrent laryngeal nerve, the superior laryngeal nerve, and the cervical sympathetic trunk. Injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve can result in vocal cord paralysis. Injury to the superior laryngeal nerve can result in dysphonia (alteration of sound pitch). Horner syndrome may result from damage to the cervical sympathetic trunk.

Disruption of the parathyroid glands may result in transient or permanent hypoparathyroidism and consequential hypocalcemia.

Recurrence of a thyroglossal duct cyst may occur following failure to remove the cyst and its tract in its entirety. This may result in subsequent procedures.

Media

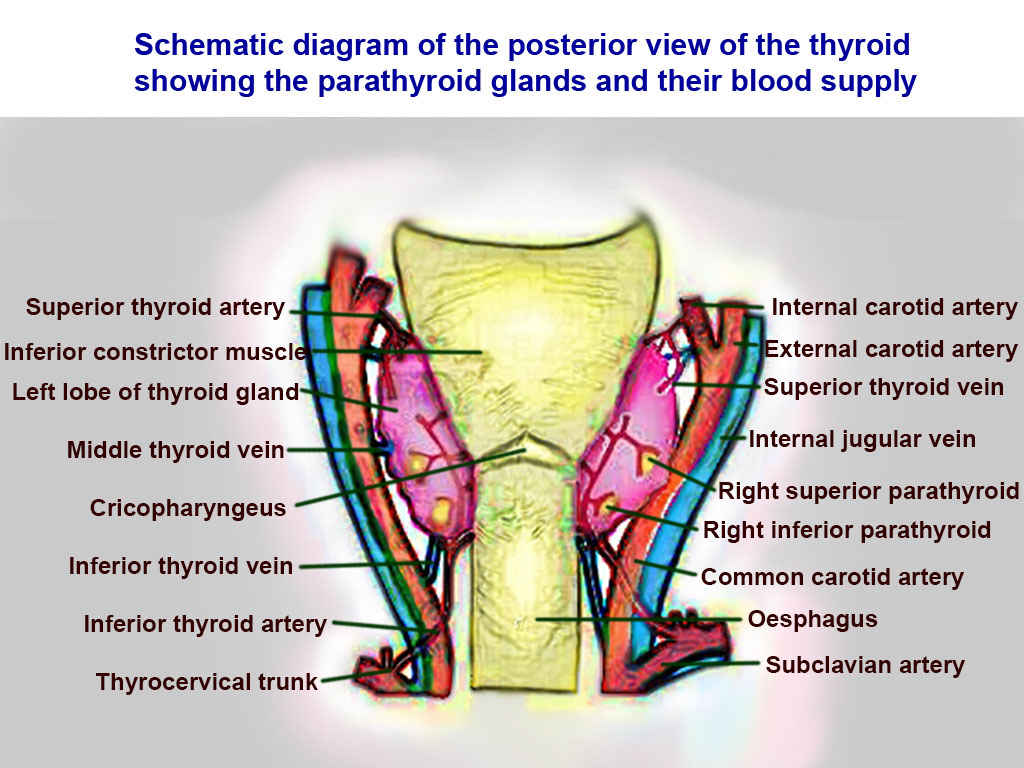

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Thyroid Arteries, Veins, and Muscles. Posterior view of thyroid includes superior thyroid, inferior constrictor, left lobe of thyroid, middle thyroid vein, cricopharyngeaus, inferior thyroid vein, inferior thyroid vein, inferior thyroid artery, thyrocervical trunk, internal carotid, external carotid, superior thyroid, internal jugular, right superior parathyroid, right inferior parathyroid, common carotid, oesphagus, and subclavian.

Contributed by T Silappathikaram

References

Ilahi A, Muco E, Ilahi TB. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Parathyroid. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725888]

Fitzpatrick TH, Siccardi MA. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Adam's Apple. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30570975]

Jacobsen B, VanKampen N, Ashurst JV. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Thyrohyoid Membrane. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422588]

Roman BR, Randolph GW, Kamani D. Conventional Thyroidectomy in the Treatment of Primary Thyroid Cancer. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 2019 Mar:48(1):125-141. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2018.11.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30717897]

Patel S, Bhatt AA. Thyroglossal duct pathology and mimics. Insights into imaging. 2019 Feb 6:10(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0694-x. Epub 2019 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 30725193]

Wiersinga WM. Graves' Disease: Can It Be Cured? Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea). 2019 Mar:34(1):29-38. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2019.34.1.29. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30912336]

Rovira A, Nixon IJ, Simo R. Papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid gland: current controversies and management. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2019 Apr:27(2):110-116. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000520. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30844924]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNaytah M, Ibrahim I, da Silva S. Importance of incorporating intraoperative neuromonitoring of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve in thyroidectomy: A review and meta-analysis study. Head & neck. 2019 Jun:41(6):2034-2041. doi: 10.1002/hed.25669. Epub 2019 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 30706616]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence