Introduction

“Eat when you can, sleep when you can, and don’t mess with the pancreas." This age-old surgical mantra is a saying to live by, but what happens if the pancreas has already been “messed with?" Pancreatic trauma is a rare but potentially catastrophic injury that can be very difficult to diagnose. Unlike the liver, kidney or spleen, conventional imaging modalities miss subtle findings associated with pancreatic injury. Post-traumatic pancreatitis may not cause alterations in blood or edema for several hours after the initial event. Diagnostic testing may require magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). A delay in diagnosis leads to complications such as infection, pseudocysts, abscess, duct stricture, peritonitis, and endocrine/exocrine insufficiency which are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Incorrect classification deters proper intervention and management. A high degree of suspicion and comprehensive knowledge is required to identify, classify, and treat traumatic pancreatic effectively. This chapter is a concise overview to further aid the care for patients who suffer traumatic pancreatic injury.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The traumatic pancreatic injury is usually a sequela of penetrating trauma. Blunt trauma (i.e., bicycle handlebar injuries in children, steering wheel injury in an adult motor vehicle collision, or direct kick in an assault) causes a sudden localized impact to the abdomen which results in compression of the intraabdominal organs against the vertebral column and can lead to pancreatic injury. Main pancreatic duct disruption is crucial to identify as it is the primary cause of delayed complications. Pancreatic injuries are rarely solitary as 90% of cases usually involve damage to another abdominal organ with duodenal-pancreatic injury being the most common.[1][3]

Epidemiology

Pancreatic injury is rare as it has been reported to occur as low as 0.2% to 1.1% of all trauma. Sixty-three percent are from penetrating gunshot and stab wounds while the remaining 37% are consequences of blunt abdominal trauma. The incidence of pancreatic injury in abdominal trauma is cited as low as 3% to 12% and 0.2% to 2% in all trauma. Mortality from pancreatic injury has ranged from 9% to 34%. A level 1 trauma center reports morbidity as high as 64%. The isolated pancreatic injury is seen in only 30% of cases traumatic pancreatic injury, and only 5% of cases are related to fatal outcomes. Blunt pancreatic trauma is more common in the pediatric population as there is less fat for insulation.[1]

Pathophysiology

The pancreas is a retroperitoneal organ which lies in transverse orientation in the epigastric region near the level of L1-L2. The pancreas has some innate protection given its location in the dorsal aspect of the abdomen. It is long, J-shaped, lobulated, and is divided histologically into two parts. The first is the endocrine pancreas that houses alpha, beta, and gamma cells responsible for glucagon, insulin, and somatostatin respectively. The second is the acinar or exocrine portion that secretes lipase, amylase, and proteolytic enzymes into the duodenum along with bile at the ampulla of Vater through the sphincter of Oddi. The main pancreatic duct of Wirsung runs transversely through the entirety of the pancreas and is responsible for delayed complications when disrupted.

Pancreatic vessels branch off the spleen and are the blood supply to the head, body, and tail, while blood drains through the splenic, superior mesenteric, and portal vein. Proximity to major blood vessels forces a difficult surgical approach in risk of massive hemorrhagic exsanguination.

Hemorrhage leads to primary mortality in pancreatic trauma. There is an increase in infectious complications with wounds that are associated with the small and large intestine as these lead to exposure to bacterial flora which progresses to gram-negative sepsis. Ductal disruption leads to a leak of proteolytic enzymes that erode into other organs leading to fistula and abscess formation at a rate of 50% and 25% respectively. Other complications include pancreatic pseudocyst which is circumscribed collection of enzymes, blood, and necrotic tissue. Less frequent complications include peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Pancreatic trauma can disrupt the endocrine function for patients as well. Consequently, patients who suffer traumatic pancreatic injury are vulnerable to immediate and delayed consequences of this disease process.[1][4]

History and Physical

Traumatic pancreatitis can be a difficult diagnosis to make and requires meticulous investigation. Damage to the pancreas is not very common and is seldom a solitary insult. Pancreatic injury is hidden in the shadows of coexisting intraabdominal injuries and its inherent retroperitoneal location. Symptoms of radiating epigastric pain to the back, nausea, and vomiting are also seen with the more commonly injured adjacent viscera. An abdominal exam is reported to have a false negative rate of 34% on initial evaluation. As the signs and symptoms are nonspecific, a high index of suspicion is necessary to prevent delayed diagnosis. [1]

Evaluation

Pancreatic injury is extremely difficult to diagnose, and most cases are not recognized until catastrophic complications develop. Laboratory testing is rarely helpful. Serum lipase and amylase are not specific or sensitive for pancreatic injury; even in complete transection or fracture of the pancreas, amylase levels are normal in 30% to 35% of patients. Amylase levels in deep peritoneal lavage have poor correlation with traumatic pancreatitis as it can be elevated in injuries to the head, neck, salivary glands, liver, duodenum, and alcohol intoxication.

Ultrasonography and radiography are integral parts of modern trauma evaluation. A plain x-ray is useful in detecting a foreign body in penetrating trauma. Ultrasound (US) is fast and accessible; however, it has imperfect sensitivity for the diagnosis of acute traumatic pancreatitis. It may show enlargement, edema, and peripancreatic fluids. Ultrasound is reliable for identifying complications from duct injury such as pseudocyst. Computerized tomography (CT) is the test of choice for the hemodynamically stable trauma patient with blunt abdominal injury however it can have difficulty identifying pancreatic injury, particularly in the near term after injury when 20% to 40% of CTs appear normal initially within 12 hours of trauma. Direct signs of injury include laceration, transaction, focal enlargement and enhancement. Secondary signs include peripancreatic fat stranding, peripancreatic fluid, hemorrhage, hematoma, and associated injury to adjacent structures. CT can identify clear signs of pancreatic injury such as the fracture or clear separation of fragments. It can also identify intrapancreatic hematoma which is very specific for traumatic pancreatitis. Wong et al. describe a CT grading system for blunt traumatic injury.

The accuracy of a CT scan identifying a traumatic major duct injury is reported as low as 43%. As poor outcomes are associated with missed ductal injury, MRCP and ERCP have become pivotal in the evaluation of the traumatic pancreatic injury. Dynamic secretin-stimulated MRCP is rapid, noninvasive, and competes with ERCP for accuracy. It can evaluate the entire pancreatic ductal system as well as fluid collections or disruptions. The main pancreatic duct is identified in 97% of cases by dynamic secretin-stimulated MRCP. ERCP is not only helpful in identifying both acute and delayed pancreatic injury but also for image-guided intervention. ERCP is the most accurate modality for diagnosing ductal injury and may be performed when there is a high index of suspicion for pancreatic injury. ERCP can treat select cases of pancreatic injury nonoperatively through ductal stenting and aids in the management of delayed complications such as pseudocyst, fistula or stricture. ERCP is not without its downsides given the potential complications of viscus perforation, pancreatitis, hemorrhage, and cholangitis.[5][6][4]

Treatment / Management

Pancreatic injury is usually accompanied by polytrauma and multiple organ damages. Initial treatment is resuscitation and hemodynamic stabilization with emphasis on hemorrhage control and minimizing spillage of gastric contents. Treatment will be dictated by damage to the major pancreatic duct, the extent of parenchyma involved, the location of the injury, patient stability, and other injuries. Conservative treatment involves nasogastric tube placement with suction, bowel rest, and nutritional support. Currently, octreotide a synthetic somatostatin analog has no defined role in the treatment of a traumatic pancreatic injury. One small study of 28 patients showed decreased complication rate with use of octreotide. However, a slightly larger study showed no difference in complication rate. ERCP-guided stent placement or drainage is the treatment for specific major pancreatic duct injury. Penetrating injury will usually require exploratory laparotomy. Morbidity and mortality greatly increase without surgical intervention within 24 hours when there is a major pancreatic injury in blunt abdominal trauma. Surgical intervention range from simple drainage, pyloric exclusion, duodenal diversion, or, in severe cases, a Whipple procedure. If the patient is hemodynamically unstable, the Whipple procedure is split into two separate surgeries: damage control and anastomoses.

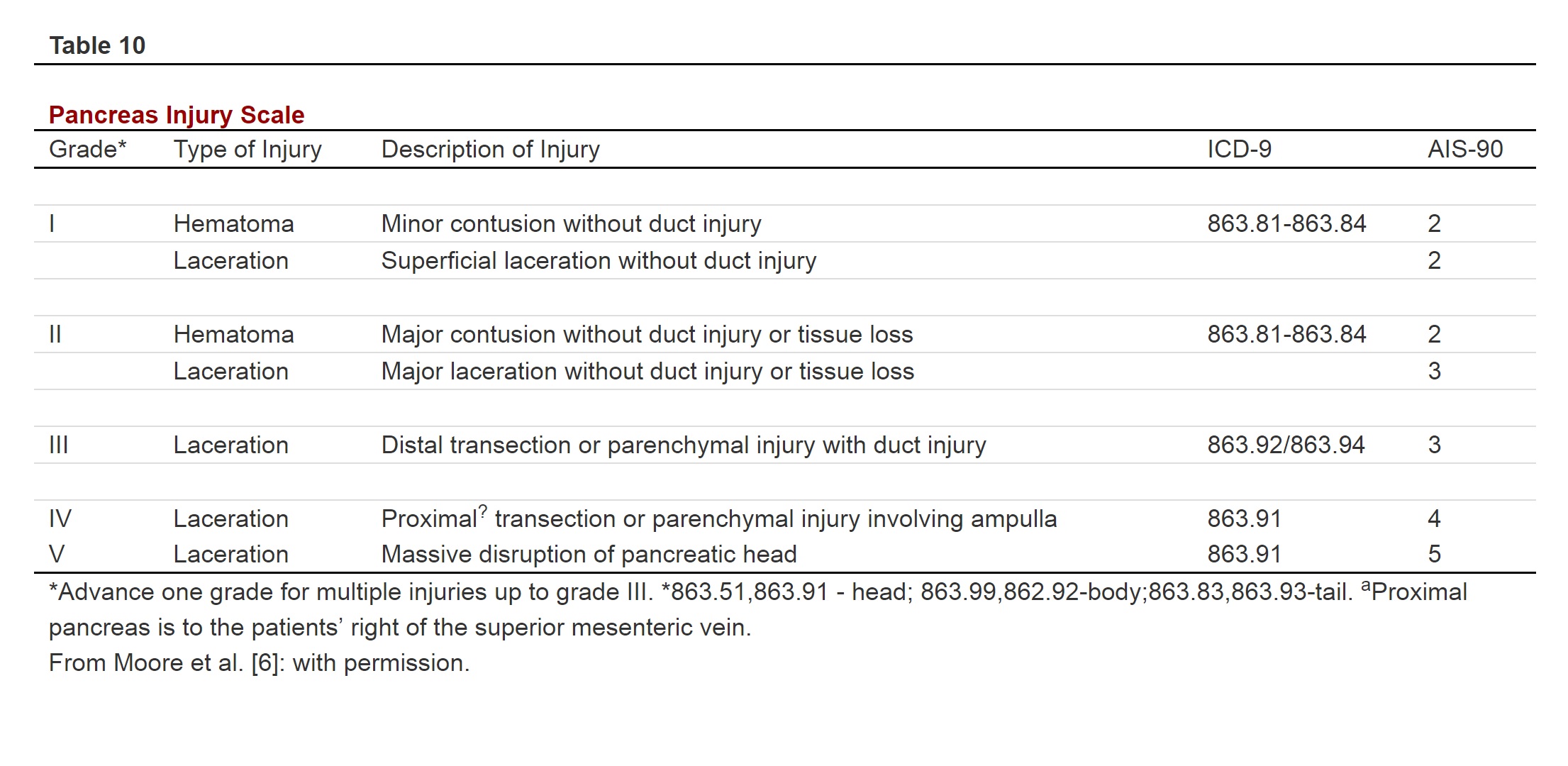

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) proposed the pancreatic Organ Injury Scale (OIS) that is accepted universally in grading pancreatic injury. The AAST pancreatic OIS utilizes CT findings and is applied to guide therapy in hemodynamically stable patients who suffer blunt pancreatic injury.

AAST Pancreatic OIS (see attached table)

The 2016 Eastern Association of the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) released several recommendations for the management of the traumatic pancreatic injury. The low-grade injury is defined as either grade I or II which calls for preoperative or intraoperative ERCP/MRCP (if there is no pancreatic ductal injury then manage conservatively. A high-grade injury is defined as grade III through V. These injuries should be treated with conditional surgical intervention; the procedural approach will be dependent on duodenal involvement. Due to limited data, there is no recommendation for when to perform pancreaticoduodenectomy. The use of octreotide is not recommended because no benefit has been shown. In regards to distal pancreatic resection, there is no recommendation on routine splenectomy.

The Pancreatic Injury Mortality Score (PIMS)

PIMS is the validated and ideal score to predict mortality from traumatic pancreatic injury. The five variables that make up the PIMS are age (older than 55), shock on admission, vascular injury, number of associated injuries and AAST pancreatic OIS. PIMS separate risk into low risk (0 to 5), medium risk (5 to 9), and high risk (9 to 20) with the associated mortality of approximately less than 1%, 15%, 50%, respectively.

PIMS Scoring (0 to 20)

Age (older than 55)

- Yes (5)

- No (0)

Shock on admission:

- Yes (5)

- No (0)

Major Vascular Injury:

- Yes (2)

- No (0)

Associated injuries:

- None (0)

- One (1)

- Two (2)

- Three or more (3)

AAST pancreatic OIS

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute pancreatitis

- Gallstone pancreatitis

- Hemorrhagic pancreatitis

- Interstitial edematous pancreatitis

- Necrotizing pancreatitis

- Nonepithelial pancreatic neoplasms

- Pancreatic atrophy

- Pancreatic clefts

- Pancreatic endocrine neoplasm

- Pancreatic lipomatosis

- Pancreatic neoplasms

- Pseudopancreatitis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pancreatic injuries if not diagnosed have high morbidity and mortality. Thus, the condition is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a radiologist, general surgeon, gastroenterologist, internist, emergency department physician, and nurse practitioner. Most of these patients also have other associated injuries and thus a thorough workup is required.

Mild pancreatic injury can be managed conservatively but disruption of the duct usually requires surgery. The outcomes depend on the age, associated injuries, the severity of the injury and response to treatment.[8][9][10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Debi U, Kaur R, Prasad KK, Sinha SK, Sinha A, Singh K. Pancreatic trauma: a concise review. World journal of gastroenterology. 2013 Dec 21:19(47):9003-11. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24379625]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAkhrass R, Yaffe MB, Brandt CP, Reigle M, Fallon WF Jr, Malangoni MA. Pancreatic trauma: a ten-year multi-institutional experience. The American surgeon. 1997 Jul:63(7):598-604 [PubMed PMID: 9202533]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHasanovic J, Agic M, Rifatbegovic Z, Mehmedovic Z, Jakubovic-Cickusic A. Pancreatic injury in blunt abdominal trauma. Medical archives (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina). 2015 Apr:69(2):130-2. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2015.69.130-132. Epub 2015 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 26005266]

Ho VP, Patel NJ, Bokhari F, Madbak FG, Hambley JE, Yon JR, Robinson BR, Nagy K, Armen SB, Kingsley S, Gupta S, Starr FL, Moore HR 3rd, Oliphant UJ, Haut ER, Como JJ. Management of adult pancreatic injuries: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2017 Jan:82(1):185-199. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001300. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27787438]

Linsenmaier U, Wirth S, Reiser M, Körner M. Diagnosis and classification of pancreatic and duodenal injuries in emergency radiology. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2008 Oct:28(6):1591-602. doi: 10.1148/rg.286085524. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18936023]

Potoka DA, Gaines BA, Leppäniemi A, Peitzman AB. Management of blunt pancreatic trauma: what's new? European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2015 Jun:41(3):239-50. doi: 10.1007/s00068-015-0510-3. Epub 2015 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 26038029]

Krige JE, Spence RT, Navsaria PH, Nicol AJ. Development and validation of a pancreatic injury mortality score (PIMS) based on 473 consecutive patients treated at a level 1 trauma center. Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) ... [et al.]. 2017 Jul-Aug:17(4):592-598. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2017.04.009. Epub 2017 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 28596059]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChen Y, Jiang Y, Qian W, Yu Q, Dong Y, Zhu H, Liu F, Du Y, Wang D, Li Z. Endoscopic transpapillary drainage in disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome after acute pancreatitis and trauma: long-term outcomes in 31 patients. BMC gastroenterology. 2019 Apr 16:19(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-0977-1. Epub 2019 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 30991953]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePereira R, Vo T, Slater K. Extrahepatic bile duct injury in blunt trauma: A systematic review. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2019 May:86(5):896-901. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002186. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31008893]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGabriel V, Grigorian A, Nahmias J, Pejcinovska M, Smith M, Sun B, Won E, Bernal N, Barrios C, Schubl SD. Risk Factors for Post-Operative Sepsis and Septic Shock in Patients Undergoing Emergency Surgery. Surgical infections. 2019 Jul:20(5):367-372. doi: 10.1089/sur.2018.186. Epub 2019 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 30950768]