Introduction

Kluver-Bucy syndrome (KBS) is a neuropsychiatric disorder due to lesions affecting bilateral temporal lobes, especially the hippocampus and amygdala.[1]

Clinical Features

- Hyperorality (A tendency or compulsion to examine objects by mouth)

- Hypermetamorphosis (Excessive attentiveness to visual stimuli with a tendency to touch every such stimulus regardless of its history or reward value)

- Hypersexuality

- Bulimia

- Placidity

- Visual agnosia and

- Amnesia.

Patients having a combination of three or more different elements listed above are described as having partial KBS.[2][3]

The clinical features of KBS were initially reported by Sanger Brown and Edward Albert Sharpey-Schäfer, two British experimental neurologists, in 1888.[4] They described the behavioral transformations after the removal of bilateral temporal lobes in monkeys. But the complete syndrome was described later by Heinrich Kluver (neuropsychologist) and Paul Clancy Bucy (neurosurgeon) in 1939, unaware of the previous reporting.[5] They described the behavioral syndrome which occurred in a Rhesus monkey (named Aurora) three weeks after bilateral temporal lobectomy. The first description of KBS in humans came from Dr. Hrayr Terzian (1925-1988) and Dr. Giuseppe Ore in 1955 in a 19-year-old man who underwent bilateral temporal lobectomy for seizures.[6][7][6] The first identified and reported case of KBS was in a 22-year-old male patient with bilateral temporal damage due to herpes simplex meningoencephalitis by Marlowe et al.[8]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

KBS is known to be associated with several pathologies. There are many case reports of several conditions (listed below) ranging from infections like shigellosis to methamphetamine withdrawal. But how KBS occurred in these conditions remains unclear.

- Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE)[9]

- Stroke (temporal lobe infarction - usually bilateral)[10][11]

- Listeria meningoencephalitis[12]

- Traumatic brain injury[13]

- Central nervous system tuberculosis[2]

- Primary cerebral Whipple disease[14]

- Alzheimer disease[15]

- Pick disease [16]

- Hypoglycemia[17]

- Acute sporadic porphyria[18]

- Huntington disease[19]

- Juvenile neuronal lipofuscinosis[20]

- Toxoplasmosis

- Epilepsy[21]

- Parkinson disease

- Heat stroke[22]

- Shigellosis[23]

- Methamphetamine withdrawal[24]

- Systemic lupus erythematosus[25]

- Anoxic-ischemic encephalopathy[26]

- Neurocysticercosis[26]

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma[27]

- Mycoplasmal bronchitis.[28]

- Methotrexate leukoencephalopathy[29]

- Subdural hygroma[30]

- Susac syndrome[31] - associated with partial KBS

- Anti-NMDAR encephalitis[32]

- Exposure to cannabis[33]

The most common pathologies leading to the development of KBS are head injury and stroke in adults and herpes simplex encephalitis in children.

Epidemiology

Human KBS is more or less restricted to case series and reports. Hence the exact prevalence is difficult to estimate.

Pathophysiology

The significant clinical symptoms of KBS are produced by the destruction of either the temporal neocortex or the amygdala bilaterally. The full syndrome is rarely seen in humans because the anterior temporal lobe dysfunction is usually less severe in humans when compared to that following total temporal lobe resection in monkeys.[34]

The exact anatomical basis of KBS is still controversial. KBS is thought to occur due to the disturbances in the temporal portions of limbic networks that connect with multiple cortical and subcortical circuits to modulate emotional behavior and affect.[34] A sine qua non for KBS is the involvement of medial temporal lobe regions along with bilateral lesions of the Ammon horn.[35] Even though KBS is always thought to follow bilateral malfunctions of the temporal lobes, it is important to note that the amygdala, uncus, hippocampus, orbitofrontal and cingulate gyri, and insular cortex have an important role in its pathogenesis.

Theories Regarding the Etiology

- Norman Geschwind's theory: Interruption of visual input to limbic circuit leading to disconnection syndrome produces KBS.[36]

- Muller theory: Disconnection of the pathways connecting the dorsomedial thalamus with the prefrontal cortex and other limbic areas leads to KBS. These pathways are essential for memory and emotional regulation.[37]

The Origin of Various Symptoms

- Rage is produced by the involvement of the ventromedian nucleus of the thalamus and amygdala.[38]

- A permanent "hypersexed state," is produced by discrete bilateral lesions of the lateral amygdaloid nucleus. Temporal lobe seizures may produce a transient state.

- Visual agnosia results from bilateral ventral temporal ablations and temporal lobectomies.

History and Physical

In Adults

- Hyperorality - Socially inappropriate lickings and a strong compulsion to place objects inside the mouth

- Hypersexuality - Lack of social restraint in terms of sexuality, with inappropriate sexual activity and attempted copulation with inanimate objects

- Eating disorder - Objects are placed in the mouth and explored with the tongue to counteract visual agnosia. Bulimia, which is an eating disorder characterized by binge eating, followed by purging, is also markedly seen and may cause weight gain.

- Placidity - Flat affect and reduced response to emotional stimuli

- Visual agnosia (Psychic blindness) - Inability to recognize familiar objects or faces presented visually

Placidity, hyperorality, and dietary changes are the most commonly occurring symptoms of KBS.

In Children

KBS in children usually occurs secondary to HSE with classic features occurring only in a few.

- Marked indifference

- Bulimia and hyperorality

- Lack of emotional attachment towards the family

- Hypersexuality:

- The frequent holding of genitals

- Intermittent pelvic thrusts

- Rubbing of genitals to the bed after lying prone

Evaluation

The diagnosis of KBS is mainly clinical. Once diagnosed, proper evaluation to find out the underlying pathology will be helpful in the overall management.

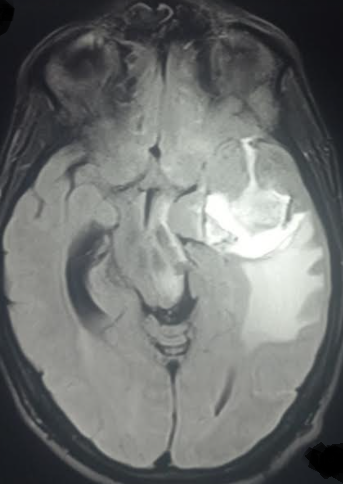

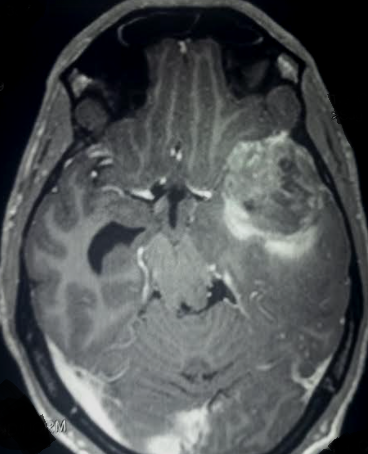

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain is useful in identifying the extent of temporal lobe damage.

An electroencephalogram is also useful to identify seizures originating especially from the temporal lobe.

In head injury and other conditions producing a long duration of loss of consciousness, the appropriate staging of the consciousness is possible with the Modified Innsbruck Remission Scale, which includes the Kluver Bucy phase as well.[39]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of KBS can be challenging due to the fact that there is no specific treatment for the condition, and the clinical course will vary from patient to patient. Most of the treatment focuses on managing the symptoms. The main drugs used in the management are:

- Mood stabilizers

- Antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors)

- Antipsychotic drugs

- Carbamazepine

- Leuprolide

Carbamazepine and leuprolide are used to reduce sexual behavioral abnormality, whereas haloperidol and anticholinergics are useful in treating behavioral abnormalities associated with KBS.[40] Carbamazepine has been found to improve outcomes in patients with KBS secondary to traumatic brain injury.[41](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

KBS requires differentiation from the following conditions:

- Alzheimer disease - Memory loss, personality changes

- Conditions causing hyperphagia - Prader-Willi syndrome and Kleine-Levin syndrome

- Frontotemporal degeneration - Progressive deterioration of intellect associated with behavioral and personality changes.

- Korsakoff syndrome - Poor memory, irritation, personality changes

Prognosis

Some KBS features (i.e., hyperorality, placidity, hypermetamorphosis) persist indefinitely, whereas others gradually resolve over several years.

The clinical course of the disease varies among the case reports.

KBS occurring secondary to epileptic seizures, infections, and traumatic brain injuries may have a better prognosis as many of the damages would be reversible if recognized early and managed appropriately.

Complications

Due to hyperorality and hypermetamorphosis, the patient may try to put whatever objects he comes across into his mouth, which can be dangerous.

Due to hypersexuality, he may try to engage in sex with others whom he does not even know, leading to criminal procedures against the patient if there is no awareness of the diagnosis.

Bulimia can cause weight gain, electrolyte disturbance, and poor oral hygiene.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients' relatives should be educated about the condition and counseled that treatment may not always be successful. They should receive information that situations may arise, which require physical patient restraint.

Pearls and Other Issues

KBS is not a life-threatening condition. But it can profoundly affect the quality of life of the patient and the carers to a great extent. Any behavioral change following lesions of temporal lobes should be watched with suspicion for the development of KBS. More research is needed into the pathophysiology of the symptoms of KBS as well as the pharmacological and nonpharmacological management methods.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A close interaction between the treating neurologist, psychiatrist, neurosurgeon, and radiologist is necessary for coming to the final diagnosis of KBS. Careful monitoring of diet is required if they have symptoms consistent with eating disorders. Staff members, including nurses, should be cognizant of hypersexual behaviors in these patients.

The outcomes for these patients are poor; they often require medications to suppress abnormal behavior, and often, physical restraints are needed. Many end up in psychiatric institutions where they remain for life.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kar SK, Das A, Pandey S, Gupta B. Kluver-Bucy Syndrome in an Adolescent Girl: A Sequel of Encephalitis. Journal of pediatric neurosciences. 2018 Oct-Dec:13(4):523-524. doi: 10.4103/JPN.JPN_70_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30937109]

Jha KK, Singh SK, Kumar P, Arora CD. Partial Kluver-Bucy syndrome secondary to tubercular meningitis. BMJ case reports. 2016 Aug 16:2016():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-215926. Epub 2016 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 27530874]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRieder HL,Snider DE Jr,Cauthen GM, Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States. The American review of respiratory disease. 1990 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 2301852]

Vannemreddy PSSV, Stone JL. Sanger Brown and Edward Schäfer before Heinrich Klüver and Paul Bucy: their observations on bilateral temporal lobe ablations. Neurosurgical focus. 2017 Sep:43(3):E2. doi: 10.3171/2017.6.FOCUS17265. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28859570]

Klüver H, Bucy PC. Preliminary analysis of functions of the temporal lobes in monkeys. 1939. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 1997 Fall:9(4):606-20 [PubMed PMID: 9447506]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTERZIAN H, ORE GD. Syndrome of Klüver and Bucy; reproduced in man by bilateral removal of the temporal lobes. Neurology. 1955 Jun:5(6):373-80 [PubMed PMID: 14383941]

Brigo F. Hrayr Terzian (1925-1988): a life between experimental neurophysiology and clinical neurology. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2021 Sep:42(9):3939-3942. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05070-z. Epub 2021 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 33495930]

Marlowe WB, Mancall EL, Thomas JJ. Complete Klüver-Bucy syndrome in man. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior. 1975 Mar:11(1):53-9 [PubMed PMID: 168031]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEikmeier G, Forquignon I, Honig H. [Klüver-Bucy syndrome after herpes simplex encephalitis]. Psychiatrische Praxis. 2013 Oct:40(7):392-3. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1343274. Epub 2013 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 23846508]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChou CL, Lin YJ, Sheu YL, Lin CJ, Hseuh IH. Persistent Klüver-Bucy syndrome after bilateral temporal lobe infarction. Acta neurologica Taiwanica. 2008 Sep:17(3):199-202 [PubMed PMID: 18975528]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOzdemir H, Rezaki M. [Klüver-Bucy-like syndrome and frontal symptoms following cerebrovascular disease]. Turk psikiyatri dergisi = Turkish journal of psychiatry. 2007 Summer:18(2):184-8 [PubMed PMID: 17566885]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCohen MJ, Park YD, Kim H, Pillai JJ. Long-term neuropsychological follow-up of a child with Klüver-Bucy syndrome. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2010 Dec:19(4):643-6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.09.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20926352]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorcos N, Guirgis H. A case of acute-onset partial Kluver-Bucy syndrome in a patient with a history of traumatic brain injury. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2014 Summer:26(3):E10-1. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13060132. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25093767]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeesch W, Fischer I, Staudinger R, Miller DC, Sathe S. Primary cerebral Whipple disease presenting as Klüver-Bucy syndrome. Archives of neurology. 2009 Jan:66(1):130-1. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.531. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19139312]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKile SJ, Ellis WG, Olichney JM, Farias S, DeCarli C. Alzheimer abnormalities of the amygdala with Klüver-Bucy syndrome symptoms: an amygdaloid variant of Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology. 2009 Jan:66(1):125-9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.517. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19139311]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCummings JL, Duchen LW. Kluver-Bucy syndrome in Pick disease: clinical and pathologic correlations. Neurology. 1981 Nov:31(11):1415-22 [PubMed PMID: 7198189]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoudjemline AM, Isapof A, Witas JB, Petit FM, Gajdos V, Labrune P. Klüver Bucy syndrome following hypoglycaemic coma in a patient with glycogen storage disease type Ib. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2010 Dec:33 Suppl 3():S477-80. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9243-y. Epub 2010 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 21103936]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuidotti TL, Charness ME, Lamon JM. Acute intermittent porphyria and the Klüver -- Bucy syndrome. The Johns Hopkins medical journal. 1979 Dec:145(6):233-5 [PubMed PMID: 513431]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJanati A. Kluver-Bucy syndrome in Huntington's chorea. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1985 Oct:173(10):632-5 [PubMed PMID: 3161995]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLanska DJ, Lanska MJ. Klüver-Bucy syndrome in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Journal of child neurology. 1994 Jan:9(1):67-9 [PubMed PMID: 8151088]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNaito K, Hashimoto T, Ikeda S. Klüver-Bucy syndrome following status epilepticus associated with hepatic encephalopathy. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2008 Feb:12(2):337-9 [PubMed PMID: 17980671]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePitt DC, Kriel RL, Wagner NC, Krach LE. Kluver-Bucy syndrome following heat stroke in a 12-year-old girl. Pediatric neurology. 1995 Jul:13(1):73-6 [PubMed PMID: 7575855]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuedalia JS, Zlotogorski Z, Goren A, Steinberg A. A reversible case of Klüver-Bucy syndrome in association with shigellosis. Journal of child neurology. 1993 Oct:8(4):313-5 [PubMed PMID: 8228026]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSamanta D. Transient Kluver-Bucy syndrome from methamphetamine withdrawal. Neurology India. 2015 Mar-Apr:63(2):267-8. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.156304. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25948002]

Lin HF, Yeh YC, Chen CF, Chang WC, Chen CS. Kluver-Bucy syndrome in one case with systemic lupus erythematosus. The Kaohsiung journal of medical sciences. 2011 Apr:27(4):159-62. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2010.12.011. Epub 2011 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 21463840]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJha S, Patel R. Kluver-Bucy syndrome -- an experience with six cases. Neurology India. 2004 Sep:52(3):369-71 [PubMed PMID: 15472430]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUnal E, Koksal Y, Baysal T, Energin Ml, Aydin K, Caliskan U. Kluver-Bucy syndrome in a boy with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatric hematology and oncology. 2007 Mar:24(2):149-52 [PubMed PMID: 17454782]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAuvichayapat N, Auvichayapat P, Watanatorn J, Thamaroj J, Jitpimolmard S. Kluver-Bucy syndrome after mycoplasmal bronchitis. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2006 Feb:8(1):320-2 [PubMed PMID: 16356778]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAntunes NL, Souweidane MM, Lis E, Rosenblum MK, Steinherz PG. Methotrexate leukoencephalopathy presenting as Klüver-Bucy syndrome and uncinate seizures. Pediatric neurology. 2002 Apr:26(4):305-8 [PubMed PMID: 11992760]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDuggal HS, Khess CR, Nizamie SH. Subdural hygroma presenting as dementia with kluver-bucy symptoms. Indian journal of psychiatry. 1999 Oct:41(4):371-3 [PubMed PMID: 21430814]

Ruiz-García RG, Chacón-González J, Bayliss L, Ramírez-Bermúdez J. Neuropsychiatry of Susac Syndrome: a Case Report. Revista Colombiana de psiquiatria (English ed.). 2021 Apr-Jun:50(2):146-151. doi: 10.1016/j.rcp.2019.10.007. Epub 2020 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 33735032]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSoni V, Sharawat IK, Kasinathan A, Saini L, Suthar R. Kluver-Bucy syndrome in a girl with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Neurology India. 2019 May-Jun:67(3):887-889. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.263181. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31347577]

Raju VV, Sankhyan N, Padhy SK. A Single Exposure to Cannabis Presenting with Klüver-Bucy Syndrome in a Child: A Rare Case Report. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2022 Feb:89(2):208. doi: 10.1007/s12098-021-03997-x. Epub 2021 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 34741255]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLanska DJ. The Klüver-Bucy Syndrome. Frontiers of neurology and neuroscience. 2018:41():77-89. doi: 10.1159/000475721. Epub 2017 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 29145186]

Olson DA. Klüver-Bucy syndrome as a result of minor head trauma. Southern medical journal. 2003 Mar:96(3):323 [PubMed PMID: 12659375]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGeschwind N. Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man: Part I. 1965. Neuropsychology review. 2010 Jun:20(2):128-57 [PubMed PMID: 20540177]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMüller A, Baumgartner RW, Röhrenbach C, Regard M. Persistent Klüver-Bucy syndrome after bilateral thalamic infarction. Neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, and behavioral neurology. 1999 Apr:12(2):136-9 [PubMed PMID: 10223262]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRajmohan V, Mohandas E. The limbic system. Indian journal of psychiatry. 2007 Apr:49(2):132-9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.33264. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20711399]

von Wild K, Laureys ST, Gerstenbrand F, Dolce G, Onose G. The vegetative state--a syndrome in search of a name. Journal of medicine and life. 2012 Feb 22:5(1):3-15 [PubMed PMID: 22574081]

Hooshmand H, Sepdham T, Vries JK. Klüver-Bucy syndrome. Successful treatment with carbamazepine. JAMA. 1974 Sep 23:229(13):1782 [PubMed PMID: 4479148]

Clay FJ, Kuriakose A, Lesche D, Hicks AJ, Zaman H, Azizi E, Ponsford JL, Jayaram M, Hopwood M. Klüver-Bucy Syndrome Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Synthesis and Review of Pharmacological Treatment From Cases in Adolescents and Adults. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2019 Winter:31(1):6-16. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.18050112. Epub 2018 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 30376788]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence