Introduction

Infective endocarditis is a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality in children and adolescents despite new advantages in management and prophylaxis. Infective endocarditis can include acute and subacute bacterial endocarditis, as well as nonbacterial endocarditis caused by viruses, fungi, and other microbiologic agents. Since the infecting organism has changed over time, diagnosis sometimes can be difficult during the early stages of the disease and is often delayed until a serious infection is already in place.[1][2][3]

In the era of interventional cardiology and radiology, infective endocarditis by Staphylococcus aureus is gaining more relevance. Nearly 30% of patients who develop infective endocarditis are dead within 12 months. Besides the infection damaging the valve, there is also a risk of embolization and stroke. The diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis are not always easy.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

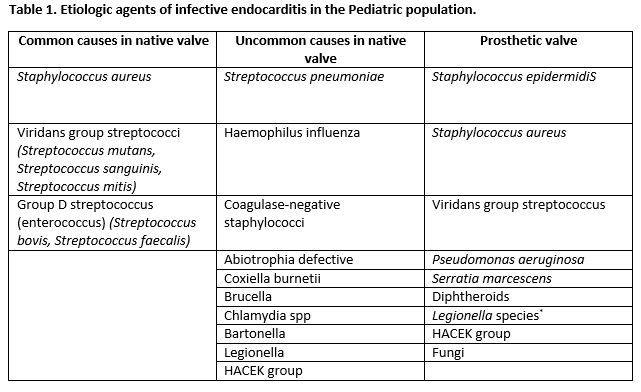

The leading cause of endocarditis in the pediatric population remains Staphylococcus aureus, followed by Viridans-type streptococci (alpha-hemolytic streptococci). Other organisms are involved but less frequently. Usually, staphylococcal endocarditis is more common in patients with an unremarkable history of heart disease. A recent dental procedure should prompt suspicions of viridans group streptococcal infection. Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Serratia marcescens are seen commonly in intravenous drug users. Fungal organisms can be an issue during open-heart surgery. In the presence of an indwelling central venous catheter, a coagulase-negative staphylococcus is frequently found as the causative agent.[4][5][6][7]

Native valve endocarditis:

- Chiefly involves the mitral valve, followed by the aortic valve

- Congenital heart disease or any defect with high flow tension is susceptible

- Mitral valve prolapse accounts for about 20% of cases

- Degenerative heart disease such as the bicuspid aortic valve, Marfan syndrome, or syphilis.

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE)

- Early PVE is caused by S aureus and S epidermidis, including MRSA

- Streptococci usually cause late PVE

Intravenous drug abuse Infective endocarditis:

- usually presents with a new murmur and/or pleuritic chest pain

- S.aureus is the most common cause, but MRSA rates are increasing

- Gram-negative organisms are rarely involved

Risk factors

- Residual valve injury

- Diabetes

- Use of steroids

- Advanced age

- Pacemaker intervention

Epidemiology

It is common to find infective endocarditis as a complication of congenital heart disease or rheumatic heart disease. However, is important to mention that infective endocarditis can present in children without any abnormal valves or cardiac malformations.

In developed countries, congenital heart disease is the most important predisposing factor. In approximately 30% of patients with infective endocarditis, a predisposing factor is acknowledged and identified.

If a history of dental procedure is recognized, the time range from the procedure may range from 1 to 6 months prior to the onset of symptoms. The existence of endocarditis after routine heart surgery is low; however, in the setting of prosthetic material use, this can be a predisposing factor.

History and Physical

An early manifestation of the disease is mild. Prolonged duration of fever that persists for several months without other manifestations may be the only symptom. On the other hand, the onset can be acute and severe with high, intermittent fever. Associated symptoms are often nonspecific and include fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, chills, nausea, and vomiting.

The presence of a new heart murmur or sounds of changing heart murmur is associated with heart failure. Splenomegaly, Roth spots, Janeway lesions, splinter hemorrhage, Osler nodes and petechial are frequently seen. Neurologic manifestations of meningismus, increased intracranial pressure, altered sensorium, focal neurologic signs, embolic strokes, cerebral abscesses, mycotic aneurysm, and hemorrhage are associated with the staphylococcal disease. Besides neurologic manifestation, staphylococcal disease can present complications like myocardial abscesses and may injure the cardiac conducting system producing heart block, or an abscess may rupture into the pericardium and cause purulent pericarditis.

The classic skin manifestation of Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, and splinter hemorrhages usually develop late in the course of the disease. The appearance of these lesions signifies the vasculitis caused by circulating antigen-antibody complexes.

Recognition of infective endocarditis is based on a high suspicion of infection in a child with an underlying risk factor.

Evaluation

Blood specimens should be attained as early as possible, even if the child has a mild illness with no significant physical findings. Three to 5 separate blood cultures should be collected after cautious preparation of the phlebotomy site. Contamination represents an issue when results come back positive for skin bacteria. Since bacteremia remains constant, the timing for collection is irrelevant. In approximately 90% of cases of endocarditis, the causative agent is identified from the first 2 blood cultures.[8][9][10]

Is well known that antimicrobial pretreatment can reduce the yield of blood culture to 50% to 60%. Hence, the microbiology laboratory needs to be informed that the patient recently used an antimicrobial pretreatment, so other methods can be used to identify the etiologic cause.[11][12][13]

When a patient has a contributing factor, the index of suspicion should be high. Echocardiography can be used to increase the probability of diagnosing endocarditis. Echocardiography can be useful in predicting embolic complications if lesions are found to be greater than 1 cm or fungal lesions are noted. Important to mention, the absence of vegetation des does not exclude endocarditis. Visible vegetations portend a poor prognosis. Echocardiogram predictors of embolism include:

- Multiple vegetations

- Vegetations more than 1 cm in diameter

- Mobile pedunculated vegetations

- Noncalcified vegetations

- Vegetations that are prolapsing

The Duke criteria aid in the diagnosis of endocarditis. The major criteria consist of positive blood cultures and evidence of endocarditis on echocardiography. The minor criteria include predisposition factors, fever, embolic-vascular signs, complex immune phenomena (glomerulonephritis, arthritis, rheumatoid factor, Osler nodes, Roth spots), single positive blood culture or serologic confirmation of infection, and echocardiographic signs not meeting the major criteria. Diagnosis of infective endocarditis is defined as 2 major criteria, 1 major and 3 minor, or 5 minor criteria.

Culture negative endocarditis occurs in 5-12% of cases. This may be due to fastidious organisms and prior antibiotic therapy.

ECG may reveal conduction delay or heart block, signaling involvement of the aortic root.

Treatment / Management

When a definitive diagnosis is made, antibiotic therapy should begin as early as possible. The choice of antibiotics, a method of administration, and length of treatment should be synchronized with pediatric infectious disease and pediatric cardiology.[14][15]

For empirical therapy, is recommended to start with vancomycin and gentamycin which will cover the most common causes including Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, and Vviridans streptococci. Is required a total of 4 to 6 weeks of treatment to cover the period of vegetation formation, which is usually several weeks. Antibiotic therapy can be adjusted depending on the clinical status of the patient and laboratory findings regarding antibiogram. Antibiotics should be administered intravenously to achieve reliable sustained therapeutic levels.

If associated complications like heart failure are present, appropriate therapy including diuretics and reducing agents can aid in the treatment. Surgical intervention for infective endocarditis is recommended in cases of the severe aortic valve, mitral valve or prosthetic valve involvement with intractable heart failure.

Fungal endocarditis is challenging to manage. Is usually seen in severely immunosuppressed patients who have had cardiac surgery. For these cases, the recommendation is amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine. In some cases, surgery may be attempted to remove the vegetation.

The role of anticoagulation is controversial as studies show worse outcomes in these patients.

Indications for surgery:

- Fungal endocarditis except for H capsulatum

- CHF that does not respond to medical treatment

- Persistent sepsis despite antibiotic therapy

- Conduction disturbance caused by aortic root involvement

- Recurrent septic emboli

- Kissing infection between the aortic and mitral valve

Differential Diagnosis

- Atrial myxoma

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Connective tissue disease

- Fever of unknown origin(FUO)

- Infective endocarditis

- Intra-abdominal infections

- Lyme disease

- Primary cardiac neoplasms

- Polymyalgia rheumatica

- Reactive arthritis

Prognosis

Infective endocarditis remains high. Morbidity occurs in more than half of children with a diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Most common complications are heart failure secondary to vegetation in the aortic or mitral valve, myocardial abscesses, toxic myocarditis, and life-threatening arrhythmias. Serious complications are systemic emboli, especially affecting the central nervous system. Other complications include a mycotic aneurysm, acquired ventricular septal defect, and heart block.

Overall mortality rates range from 7-15%.

Complications

- Pericarditis

- MI

- Valvular insufficiency

- CHF

- Myocardial abscess, conduction block

- Sinus of Valsalva aneurysm

- Arthritis

- Stroke

- Glomerulonephritis

- Arterial emboli

Deterrence and Patient Education

There has been a significant reduction in the incidence of infective endocarditis in patients with a history of procedure, thanks to the recommendation of prophylactic treatment. However, not all procedures need prophylaxis.

In 2007, the AHA modified their infective endocarditis prophylaxis guidelines, and the indications for prophylaxis were reduced for dental procedures, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal tract procedures.[8][16]

Indications for prophylaxis based on 2007 AHA:

- Prosthetic cardiac valve or prosthetic material used for cardiac valve repair

- Previous infective endocarditis

Cardiac Heart Disease (CHD) with:

- Unrepaired cyanotic CHD (including shunts and conduits)

- CHD entirely repaired with prosthetic material or device, during the first 6 months after the procedure

- Repaired CHD with residual defects to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device

- Cardiac transplantation recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy

The particular individual condition of these recommendations makes reasonable direct consultation with pediatric cardiology to determine the ongoing need for prophylaxis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Endocarditis is a serious life-threatening disorder that is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a cardiologist, neurologist, infectious disease expert, cardiac surgeon, internist, pharmacist and ICU nurses. Endocarditis has very high morbidity and while the treatment does work, the key today is to try and prevent it in the first place. When patients present, clinicians should:

- Consider endocarditis in a patient with a history of IV drug abuse

- Do not administer antibiotics to a febrile patient without first obtaining a minimum of 2 sets of blood cultures

- When appropriate provide antibiotic prophylaxis prior to surgery and dental procedures.

- If the patient is bacteremic, avoid central lines. If there is no other option, the administer bactericidal agents at the same time.

The key is to make a prompt diagnosis and start antibiotic treatment. Patients should get serial echos to determine if the treatment is working and assess the valve function. In some cases, valve replacement may be required. The nurse practitioner and pharmacist must be aware of conditions that need antibiotic prophylaxis prior to any surgery or dental procedure. Further, patients need to be told to stop IV drug abuse. The interprofessional team should follow every patient with endocarditis to ensure that optimal care is provided.

Outcomes

Even with optimal treatment, endocarditis is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Healthcare workers should be aware of new endocarditis prophylactic guidelines.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rogolevich VV, Glushkova TV, Ponasenko AV, Ovcharenko EA. [Infective Endocarditis Causing Native and Prosthetic Heart Valve Dysfunction]. Kardiologiia. 2019 Apr 13:59(3):68-77. doi: 10.18087/cardio.2019.3.10245. Epub 2019 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 30990144]

Jillella DV, Wisco DR. Infectious causes of stroke. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2019 Jun:32(3):285-292. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000547. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30973394]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSotero FD, Rosário M, Fonseca AC, Ferro JM. Neurological Complications of Infective Endocarditis. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2019 Mar 30:19(5):23. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-0935-x. Epub 2019 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 30927133]

Elbatarny M, Bahji A, Bisleri G, Hamilton A. Management of endocarditis among persons who inject drugs: A narrative review of surgical and psychiatric approaches and controversies. General hospital psychiatry. 2019 Mar-Apr:57():44-49. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.01.008. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30908961]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElagha A, Mohsen A. Cardiac MRI clinches diagnosis of Libman-Sacks endocarditis. Lancet (London, England). 2019 Apr 27:393(10182):e39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30770-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31034381]

Bekker T, Govind A, Weber DM. A Case of Polymicrobial, Gram-Negative Pulmonic Valve Endocarditis. Case reports in infectious diseases. 2019:2019():6439390. doi: 10.1155/2019/6439390. Epub 2019 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 31032128]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcCann M, Gorman M, McKeown B. No Fever, No Murmur, No Problem? A Concealed Case of Infective Endocarditis. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2019 Aug:57(2):e45-e48. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.03.002. Epub 2019 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 31029399]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarg P, Ko DT, Bray Jenkyn KM, Li L, Shariff SZ. Infective Endocarditis Hospitalizations and Antibiotic Prophylaxis Rates Before and After the 2007 American Heart Association Guideline Revision. Circulation. 2019 Jul 16:140(3):170-180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037657. Epub 2019 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 31023074]

Borger P, Charles EJ, Smith ED, Mehaffey JH, Hawkins RB, Kron IL, Ailawadi G, Teman N. Determining Which Prosthetic to Use During Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients Aged Younger than 70 Years: A Systematic Review of the Literature. The heart surgery forum. 2019 Feb 28:22(2):E070-E081. doi: 10.1532/hsf.2131. Epub 2019 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 31013214]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBamford P, Soni R, Bassin L, Kull A. Delayed diagnosis of right-sided valve endocarditis causing recurrent pulmonary abscesses: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2019 Apr 19:13(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s13256-019-2034-7. Epub 2019 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 30999926]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGalar A, Weil AA, Dudzinski DM, Muñoz P, Siedner MJ. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2019 Mar 20:32(2):. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00041-18. Epub 2019 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 30760474]

Martínez PA, Guerrero M, Santos JÉ, Hernández MS, Mercado MC. [Pediatric clinical experience in infectious endocarditis due to Candida spp]. Revista chilena de infectologia : organo oficial de la Sociedad Chilena de Infectologia. 2018:35(5):553-559. doi: 10.4067/s0716-10182018000500553. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30725003]

Samaroo-Campbell J, Hashmi A, Thawani R, Moskovits M, Zadushlivy D, Kamholz SL. Isolated Pulmonic Valve Endocarditis. The American journal of case reports. 2019 Feb 4:20():151-153. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.913041. Epub 2019 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 30713335]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnguita P, Anguita M, Castillo JC, Gámez P, Bonilla V, Herrera M. Are Dentists in Our Environment Correctly Following the Recommended Guidelines for Prophylaxis of Infective Endocarditis? Revista espanola de cardiologia (English ed.). 2019 Jan:72(1):86-88. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2018.04.029. Epub 2018 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 30585156]

Keller K, Hobohm L, Munzel T, Ostad MA. Incidence of infective endocarditis before and after the guideline modification regarding a more restrictive use of prophylactic antibiotics therapy in the USA and Europe. Minerva cardioangiologica. 2019 Jun:67(3):200-206. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4725.19.04870-9. Epub 2019 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 30724268]

Ibrahim AM, Siddique MS. Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis Prophylaxis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422578]