Introduction

The masseter is one of the muscles of mastication. It is a powerful superficial quadrangular muscle originating from the zygomatic arch and inserts along the angle and lateral surface of the mandibular ramus. The masseter is primarily responsible for the elevation of the mandible and some protraction of the mandible. It receives its motor innervation from the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The blood supply is primarily from the masseteric artery, a branch of the internal maxillary artery.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Structure

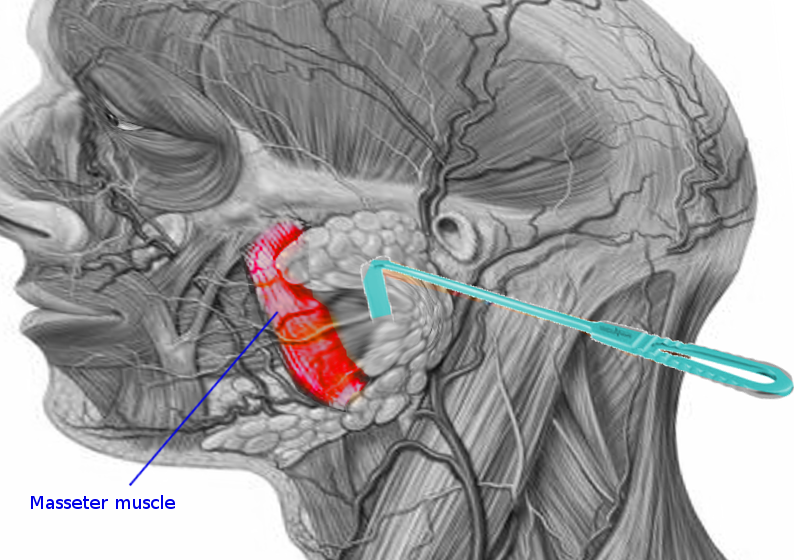

The masseter muscle is one of the muscles of mastication. It is a powerful superficial quadrangular muscle with two divisions: superficial and deep. The superficial portion of the masseter muscle originates from a thick aponeurosis on the temporal process of the zygomatic bone and the anterior two-thirds of the inferior border of the zygomatic arch. The fibers of the superficial portion pass inferior-posteriorly over the deep portion and insert onto the angle of the mandible (masseteric tubercle) and the inferior portion of the lateral surface of the mandibular ramus. The superficial masseter muscle has a quadrangular shape appearance on gross examination due to its origins and insertions. The deep portion of the masseter muscle originates from the entire surface of the zygomatic arch. The fibers run inferiorly and insert along the mandibular ramus superior to the masseter muscle’s superior portion. Anteriorly, the deep portion is covered by the superior portion of the masseter, while posteriorly, the parotid gland covers the deep portion.

Function

The masseter muscle is one of the four muscles responsible for the action of mastication (chewing). When the masseter contracts it causes powerful elevation of the mandible causing the mouth to close. Its insertion along the angle and lateral surface of the ramus also allows it to aid in the protrusion of the mandible allowing for the anterior motion of the jaw.

Embryology

Beginning in week 4, the pharyngeal apparatus forms which involves the paired pharyngeal arches, grooves, and pouches. The masseter muscle is a muscle of mastication formed from paraxial mesoderm mesenchyme of pharyngeal arch one (mandibular arch). Each of the pharyngeal arches is a core of mesenchyme covered by a layer of ectoderm externally and a layer of endoderm internally. Somitomeres are loose clusters of cells that develop alongside the neural tube and notochord. There are seven cranial pairs of somitomeres which invade the pharyngeal arches to form the myoblasts that give rise to the larynx, pharynx, and muscles of facial expression and mastication (including the masseter muscle).[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The masseter muscle primarily gets its vascular supply from the masseteric artery, a branch of the maxillary artery (formerly the internal maxillary artery). The maxillary artery comes off the external carotid artery behind the neck of the mandible. The maxillary artery divides into the mandibular, pterygoid, and pterygopalatine portions. The pterygoid portion (muscular portion, the second portion) has four main branches including the masseteric artery, pterygoid branches, deep temporal arteries, and the buccal artery. The masseteric artery is a small branch that passes through the mandibular notch of the mandible into the deep surface of the masseter muscle. The masseteric artery anastomoses with branches of the facial artery (formerly the external maxillary artery) and the transverse facial artery.[2]

Nerves

The masseteric nerve innervates the masseter muscle. The masseteric nerve is a branch of the mandibular division (V3) of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). The trigeminal nerve carries both sensory and motor fibers. Sensory fibers travel along the trigeminal nerve, enter the trigeminal ganglion and travel to their final destinations via V1 (ophthalmic), V2 (maxillary) and V3 (mandibular) divisions. The motor fibers of the trigeminal nerve do not synapse within the trigeminal ganglion, but rather bypass the trigeminal ganglion via the portio minor, a small branch of the trigeminal nerve which passes inferior to the trigeminal ganglion and through the foramen ovale, where it then rejoins the mandibular nerve. The mandibular nerve (V3) splits into anterior and posterior trunks, with the anterior portion supplying motor innervation to the muscles of mastication, and sensory innervation to the buccal (cheek) area. The masseteric nerve branches off of the mandibular nerve and crosses over the mandibular notch with the masseteric artery to the deep portion of the masseter muscle where it supplies motor innervation.[3][4]

Muscles

The classification of the muscles of mastication refers to four main muscles including the masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, and lateral pterygoid. The actions of the muscles of mastication open and close the mouth by influencing motion on the mandible. The four muscles separate into a superficial group involving the masseter and temporalis muscles, and a deep group involving the medial and lateral pterygoids.

The masseter muscle provides powerful elevation and protrusion of the mandible by originating from the zygomatic arch and inserting along the angle and lateral surface of the mandible. The temporalis muscle originates from the floor of the temporal fossa and inserts onto the coronoid process of the mandible. Contraction causes elevation of the mandible and retraction of the mandible. The medial pterygoid originates from two heads, the medial surface of the lateral pterygoid plate and the tuberosity of the maxilla, and inserts along the medial surface of the mandibular ramus. Contraction of the medial pterygoid is similar to the masseter muscle causing elevation and protrusion of the mandible. The lateral pterygoid also originates from two heads, the infratemporal surface/crest of the great wing of the sphenoid and the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid plate, and inserts at the joint capsule of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), the articular disc of the TMJ, and the condylar neck of the mandible. Contracting this muscle allows for the protraction of the mandible and anterior motion of the TMJ allowing for the mouth to open. The lateral pterygoid is the only muscle to actively oppose the other muscles of mastication and allow for depression of the mandible.

Physiologic Variants

The masseter muscle is relatively well conserved across the human population as well as the animal kingdom as a muscle of mastication. The most noticeable difference is masseteric hypertrophy which is characteristic in populations of Asian descent. Masseteric hypertrophy characteristically shows as a benign condition of enlargement of the masseter muscles leading to a square jawline shape, which is a frequent target for esthetic treatments and botox requests.[5]

Surgical Considerations

Performing surgery near the masseters requires consideration for the structures running near or originating from the muscle. Surgery of the masseter muscle is a component of facelift procedures, treatment of masseteric enlargement, or trauma. Careful consideration must be placed to not damage the masseteric ligament, fibers of the risorius muscle, and branches of the facial nerve.[6][7]

Clinical Significance

Masseter Muscle Rigidity

Masseter muscle rigidity (MMR), also known as "jaws of steel," occurs following a dose of succinylcholine and is defined as limb muscle flaccidity with jaw muscle tightness. There is a variable presentation from complete trismus and severe spasticity to a tight jaw response, which becomes concerning as the patient is unable to be adequately intubated, leading to an increased risk of malignant hyperthermia in the patient.

Masseter Reflex

The masseter reflex, also known as the mandibular reflex or jaw-jerk reflex, involves opening the mouth and placing a finger on the chin of the patient and striking the finger with a reflex hammer. The downward force can cause a reflex action in the masseter muscles resulting in an elevation of the mandible. The normal response is very little to no reflex activity, but with a brainstem lesion involving an upper motor neuron lesion, hyperreflexia of the masseteric reflex is possible.[8]

Tetanus Toxin

Tetanus toxin comes from the gram-positive spore-forming bacteria Clostridium tetani. Tetanus toxin enters the body, binds to peripheral neurons, and is transported retrogradely to the spinal cord or brainstem. Once in the central nervous system tetanus toxin inhibits the vesicular release of inhibitory neurotransmitters, glycine. This disinhibition of lower motor neurons leads to sustained contractures and muscle rigidity including opisthotonus, respiratory failure, trismus, and dysphagia. Trismus is muscle rigidity and spasms primarily of the masseter and temporalis muscle leading to an inability to open the mouth and leading to smile characteristically called risus sardonicus.[9]

Media

References

Leperchey F. [Embryogeny of facial, mastication, tongue, palate and neck muscles (author's transl)]. Revue de stomatologie et de chirurgie maxillo-faciale. 1979:80(2):45-67 [PubMed PMID: 379971]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOtake I, Kageyama I, Mataga I. Clinical anatomy of the maxillary artery. Okajimas folia anatomica Japonica. 2011 Feb:87(4):155-64 [PubMed PMID: 21516980]

Ghatak RN, Helwany M, Ginglen JG. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Mandibular Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939597]

Shankland WE 2nd. The trigeminal nerve. Part IV: the mandibular division. Cranio : the journal of craniomandibular practice. 2001 Jul:19(3):153-61 [PubMed PMID: 11482826]

Yeh YT, Peng JH, Peng HP. Literature review of the adverse events associated with botulinum toxin injection for the masseter muscle hypertrophy. Journal of cosmetic dermatology. 2018 Oct:17(5):675-687. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12721. Epub 2018 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 30091170]

Schultz BD, Gray R, Knobel D, Tanna N, Setabutr D, Cheng JA, Ortiz R, Bastidas N. Minimally Invasive Approach for Resection of Masseteric Vascular Malformations. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Sep:29(6):e596-e598. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004642. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29863563]

Alvernia JE, Hidalgo J, Sindou MP, Washington C, Luzardo G, Perkins E, Nader R, Mertens P. The maxillary artery and its variants: an anatomical study with neurosurgical applications. Acta neurochirurgica. 2017 Apr:159(4):655-664. doi: 10.1007/s00701-017-3092-5. Epub 2017 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 28191601]

Lobbezoo F, van der Glas HW, van der Bilt A, Buchner R, Bosman F. Sensitivity of the jaw-jerk reflex in patients with myogenous temporomandibular disorder. Archives of oral biology. 1996 Jun:41(6):553-63 [PubMed PMID: 8937646]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHassel B. Tetanus: pathophysiology, treatment, and the possibility of using botulinum toxin against tetanus-induced rigidity and spasms. Toxins. 2013 Jan 8:5(1):73-83. doi: 10.3390/toxins5010073. Epub 2013 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 23299659]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence