Introduction

Treadmill stress testing is a form of cardiovascular stress testing that uses exercise with electrocardiography (ECG) and blood pressure monitoring. This form of stress testing is usually performed with exercise protocols using either a treadmill or bicycle. In addition, patients who are unable to exercise may benefit from the administration of a pharmacologic agent that stimulates the heart's activity, simulating exercise-induced changes.

With treadmill stress testing, providers can determine a patient's functional capacity, assess the probability and extent of coronary artery disease (CAD), and assess the risks, prognosis, and effects of therapy.[1] Observations from the Henry Ford exercise testing (FIT) study appear to suggest a graded and inverse correlation between cardiorespiratory fitness and incidental atrial fibrillation, especially for obese patients.[2]

Exercise Physiology

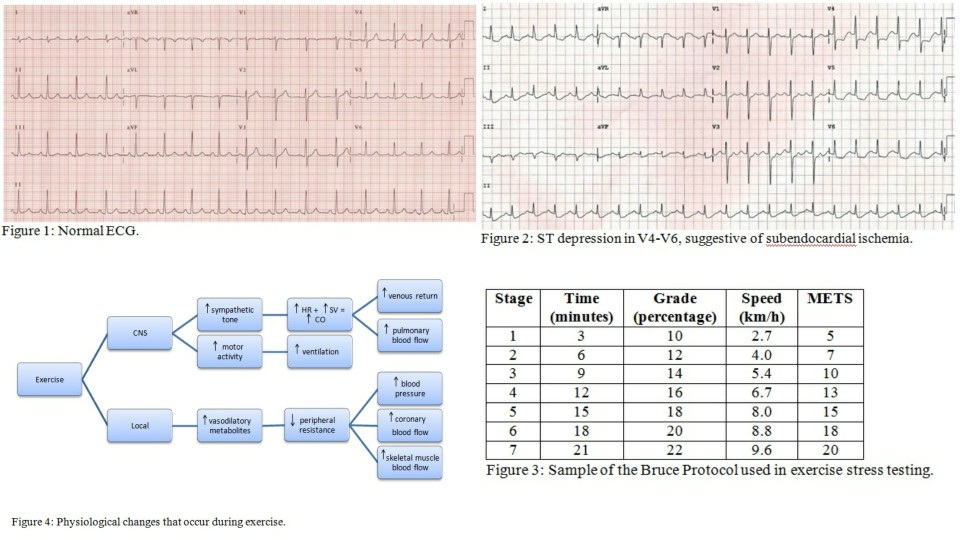

Exercise is associated with sympathetic stimulation and changes in the coronary vasomotor tone, which affects coronary blood flow. Several studies have reported that the coronaries dilate during exercise.[3] Some reported mechanisms contributing to this dilatation include the release of vasoactive substances from the endothelium due to increased myocardial oxygen consumption, passive relaxation due to the increase in coronary arterial pressure, and endothelium-mediated limitation of constrictor effects of catecholamine.

During exercise, the increase in myocardial oxygen demand and coronary vasodilation allows for increased oxygen delivery which is crucial to myocardial perfusion, thereby preventing ischemia. Through this hyperemic effect, providers can identify ischemia, as stenotic vessels do not vasodilate as well as normal vessels.[4]

Due to sympathetic stimulation and vagal inhibition, an increase in stroke volume, heart rate, and cardiac output is noted. Alveolar ventilation and venous return also increase as a consequence of selective vasoconstriction. The hemodynamic response depends on the amount of muscle mass involved, exercise intensity, and overall conditioning. As exercise progresses, skeletal muscle blood flow increase and peripheral resistance decrease leading to a rise in systolic blood pressure (SBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and pulse pressure.[5] Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) may remain unchanged, slightly increase, or slightly decrease.

The age-predicted maximum heart rate is a useful measure for estimating the adequacy of stress on the heart to induce ischemia. The goal is usually 85% of the age-predicted maximum heart rate, calculated by subtracting the patient's age from 220.[6][7][8]

Indications

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Indications

Treadmill stress testing is indicated for the diagnosis and prognosis of coronary artery disease (CAD). This is the initial investigation of choice in patients with a normal or near-normal resting ECG capable of performing adequate exercise.[9][1] Indications for treadmill testing include:

- Symptoms suggesting myocardial ischemia

- Acute chest pain in patients excluded for acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

- Recent ACS treated without coronary angiography or incomplete revascularization

- Known CAD with worsening symptoms

- Prior coronary revascularization (5 years or longer after coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG] or two years or less after percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI])

- Valvular heart disease (to assess exercise capacity and need for surgical intervention)

- Certain cardiac arrhythmias to assess chronotropic competence

- Newly diagnosed heart failure or cardiomyopathy[1][8]

Contraindications

Absolute Contraindications

- Acute myocardial infarction within 2 to 3 days

- Unstable angina not previously stabilized by medical therapy

- Uncontrolled cardiac arrhythmias causing symptoms or hemodynamic compromise[10]

- Symptomatic severe aortic stenosis[11]

- Uncontrolled symptomatic heart failure

- An acute pulmonary embolus or pulmonary infarction

- Severe pulmonary hypertension

- Acute myocarditis or pericarditis, or endocarditis

- Acute aortic dissection

Relative Contraindications (can be overlooked if the benefits of treadmill stress testing outweigh the risks)

- High-grade AV blocks

- Severe hypertension (systolic greater than 200 mmHg, diastolic greater than 110 mmHg, or both)

- Inability to exercise given extreme obesity or other physical/mental impairment[8][12]

- Left main coronary stenosis

- Moderate stenotic valvular heart disease

- Electrolyte abnormalities

- Tachyarrhythmias or bradyarrhythmias

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and any other forms of outflow tract obstruction[13]

- Mental or physical impairment leading to an inability to exercise adequately

Preparation

Treadmill stress testing is generally safe. Complications are rare, and the frequency of serious adverse cardiac events (i.e., myocardial infarction, sustained ventricular arrhythmia, and death) has been estimated to be approximately 1 in 10,000 patients.

All persons conducting the treadmill stress test should be trained to diagnose and manage complications should they arise. Emergency resuscitation equipment and drugs should also be readily available. The patient should be explained about the procedure, and consent should be obtained before the procedure.

Technique or Treatment

Treadmill stress testing is performed in a designated lab, supervised by a trained healthcare provider. Electrodes are placed on the chest and attached to an ECG machine, recording the heart's electrical activity. The resting ECG, heart rate, and blood pressure are obtained prior to starting the exercise regimen.

The baseline ECG should be evaluated closely prior to starting the exercise portion of the test. Several baseline ECG changes can obscure the test results, making it difficult for the provider to interpret the results in terms of ischemia. Such baseline changes include ST-segment changes that are greater than or equal to 1 mm, left bundle branch block, ventricular paced rhythm, left ventricular or right ventricular hypertrophy, ventricular pre-excitation (i.e., WPW syndrome), T wave inversions due to strain pattern or previous injury, conduction abnormalities, and medication-induced ST-T wave changes. If any of these ECG abnormalities are noted, the test should be performed with the addition of an imaging modality. The resting ECG is usually obtained both supine and standing since patient position can influence the QRS and T wave axes. Whether with imaging or without, treadmill stress testing is more helpful in excluding CAD than confirming it.[14]

Once it is determined that there are no limiting factors based on baseline ECG, the patient is placed on a treadmill with a designed protocol that increases in intervals as they exercise. Blood pressure and heart rate are monitored throughout exercise, and the patient is monitored for any developing symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, or extreme fatigue. The Bruce protocol is the most common one used during treadmill exercise stress testing.[15] This protocol is divided into successive 3-minute stages, each requiring the patient to walk faster and at a steeper grade. The testing protocol could be adjusted to a patient's tolerance, aiming for 6 to 12 minutes of exercise duration. There is a modified Bruce protocol for those who cannot exercise vigorously, adding two lower workload stages to the beginning of the standard Bruce protocol, both of which require less effort than stage 1. There are a number of other protocols for patients with a limited exercise tolerance; however, other methods that do not include exercise are also available for such patients.

During the exercise test, data about heart rate, blood pressure, and ECG changes should be obtained at the end of each stage. At any time, an abnormality is detected with cardiac monitoring. Heart rate and systolic blood pressure should rise with each stage of exercise until a peak is achieved. Patients should be questioned about any symptoms they experience during exercise. All patients should be monitored closely during recovery until heart rate and ECG are back to baseline, as arrhythmias and ECG changes can still develop.

It is unnecessary to stop exercise at the onset of mild symptoms if no abnormalities are noted on ECG and the patient is hemodynamically stable. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines have specified indications for the termination of exercise testing. The following are the absolute indications for termination of testing:

-

A drop in systolic blood pressure of greater than 10 mmHg from baseline when accompanied by other indications of ischemia.

-

Moderate-to-severe angina

-

Increasing neurologic symptoms, such as ataxia, dizziness, near-syncope

-

Signs of impaired perfusion, such as cyanosis or pallor

-

Technical difficulties in monitoring ECG tracings or systolic blood pressure

-

Patient's desire to stop

-

Sustained ventricular tachycardia

-

ST-elevation of more than 1 mm in leads without diagnostic Q waves, other than V or aVR[16]

Relative indications for the termination of the procedure include the following:

-

A drop in systolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg or more from baseline in the absence of other evidence of ischemia

-

ST or QRS changes (excessive horizontal or downsloping ST depression of more than 2 mm) or marked axis shift

-

Arrhythmias, such as supraventricular tachycardia, multifocal premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), heart block, or bradyarrhythmias

-

Fatigue, shortness of breath, leg cramps, wheezing, or claudication

-

Development of intraventricular conduction delay or bundle branch block that cannot be differentiated from ventricular tachycardia

-

Increasing chest pain

-

Hypertensive response (systolic blood pressure of 250 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure higher than 115 mmHg, or both)[17]

At the conclusion of testing, a report should be included. This report should outline the baseline ECG interpretation, baseline heart rate, and blood pressure, ECG changes during exercise, including the presence of arrhythmia/ectopy and the onset of such changes, maximal heart rate and blood pressure during exercise, estimated exercise capacity in metabolic equivalents of task (METs), exercise duration and stage completed, symptoms experienced during exercise and the reason for terminating the test.

A normal test is when a patient's blood pressure and heart rate increase appropriately to graded exercise. There should be no ECG changes suggestive of ischemia and no arrhythmias during testing. Failure of the blood pressure to increase or decrease with signs of ischemia has prognostic significance. Angina or significant ST depression (greater than 2 mm) before completing stage 2 of the Bruce protocol and/or ST depressions that persist for more than 5 minutes into recovery suggest severe ischemia and high risk for coronary events. Exercise testing will either be positive, negative, equivocal, or uninterpretable if there is a limiting factor such as heart rate.

A Duke treadmill score (DTS) is a validated scoring system that can assist with the risk assessment of a patient who has undergone an exercise stress test.[18] The DTS was developed to provide accurate diagnostic and prognostic information for evaluating patients with suspected coronary artery disease. The DTS uses three parameters: exercise time, ST-segment deviation (depression or elevation), and exertional angina to determine if patients are at a low, intermediate, or high risk for ischemic heart disease. The typical range is from +15 to -25. If a patient's score is greater than or equal to 5, they are considered low risk, while those who score less than or equal to -11 are considered high risk. This scoring system predicts 5-year mortality, where low-risk scores have a 5-year survival of 97%, intermediate-risk scores have a 5-year survival of 90%, and high-risk scores indicate a 5-year survival of about 65%. Patients with an intermediate risk assessment should generally be referred for additional risk stratification with an imaging modality.[7][19][20]

Complications

A treadmill stress test is generally considered safe, and its complications are rare. However, the following are the possible complications of a treadmill stress test:

- Hypotension can happen during or immediately after exercise, potentially causing the patient to feel dizzy.[21] The problem generally goes away after stopping exercise.

- Arrhythmias that occur during treadmill stress testing generally stop soon after the termination of the test.

- Although very rare, treadmill stress testing could possibly cause a myocardial infarction.

Patients should be instructed not to eat, drink, or smoke for at least three hours before the examination, as this maximizes exercise capacity. The patient should bring comfortable exercise clothing and walking shoes to the testing facility. The healthcare professional performing the test should explain the benefits, risks, and possible complications to the patient before testing.

Medications should be discussed with the patient beforehand, as some drugs such as beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, digoxin, and anti-arrhythmic medications can affect the maximal heart rate achieved. An ischemic response can also be affected if patients are taking nitrates. A thorough history and physical examination should be performed on all patients before referral for exercise stress testing.[22]

Clinical Significance

Patients with abnormal stress testing may or may not have coronary artery disease depending upon the diagnostic accuracy of the test performed and the pretest likelihood of each patient. The ACC/AHA guidelines suggest that exercise radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging or exercise echocardiography have potential use as follow-up tests in patients with intermediate or high risk. If follow-up testing is positive, patients may benefit from guideline-directed medical therapy versus cardiac catheterization with revascularization. The choice of revascularization and the type of procedure is dependent upon coronary anatomy, left ventricular systolic function, and the presence or absence of comorbidities such as diabetes. Patients should have an in-depth discussion with their provider regarding the next steps involved when an exercise stress test is reported to be positive or uninterpretable.[22][7][23]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

When patients with atypical chest pain or new-onset heart failure present to the primary care provider, internist, and nurse practitioner, one of the investigations to assess the heart is a treadmill test. The test is usually performed by a cardiologist. It is helpful as a part of diagnosing patients with known or suspected coronary disease and provides significant prognostic information for patients with known disease.

Current guidelines suggest that exercise tests with imaging or echocardiography can be used as follow-up tests in intermediate or high-risk patients. If follow-up testing is positive, patients may benefit from guideline-directed medical therapy versus cardiac catheterization with revascularization. The healthcare providers should educate the patient on what the exercise stress test involves, how it is performed, and the type of results it can reproduce.[22][7][23]

Treadmill stress testing requires the coordinated efforts of an interprofessional healthcare team that includes cardiologists, family clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs, PAs), and nurses. All team members must know the parameters of stress testing, contraindications, interpretation, and signs that the test may need to be terminated earlier. Any concerns noted by any team member should be documented in the patient's health record and communicated to other interprofessional team members. Proper cardiac stress testing can prevent more serious cardiac events by helping initiate therapeutic interventions earlier and optimize patient outcomes. The interprofessional paradigm is the best means by which to accomplish this. [Level 5]

Media

References

Acampa W, Assante R, Zampella E. The role of treadmill exercise testing in women. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2016 Oct:23(5):991-996. doi: 10.1007/s12350-016-0596-y. Epub 2016 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 27457528]

Qureshi WT, Alirhayim Z, Blaha MJ, Juraschek SP, Keteyian SJ, Brawner CA, Al-Mallah MH. Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Risk of Incident Atrial Fibrillation: Results From the Henry Ford Exercise Testing (FIT) Project. Circulation. 2015 May 26:131(21):1827-34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014833. Epub 2015 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 25904645]

Gorman MW, Feigl EO. Control of coronary blood flow during exercise. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2012 Jan:40(1):37-42. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3182348cdd. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21918457]

Bruning RS, Sturek M. Benefits of exercise training on coronary blood flow in coronary artery disease patients. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2015 Mar-Apr:57(5):443-53. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.10.006. Epub 2014 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 25446554]

Laukkanen JA, Kurl S. Blood pressure responses during exercise testing-is up best for prognosis? Annals of medicine. 2012 May:44(3):218-24. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.560180. Epub 2011 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 21345155]

Poehling CP, Llewellyn TL. The Effects of Submaximal and Maximal Exercise on Heart Rate Variability. International journal of exercise science. 2019:12(2):9-14 [PubMed PMID: 30761192]

Pargaonkar VS, Kobayashi Y, Kimura T, Schnittger I, Chow EKH, Froelicher VF, Rogers IS, Lee DP, Fearon WF, Yeung AC, Stefanick ML, Tremmel JA. Accuracy of non-invasive stress testing in women and men with angina in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. International journal of cardiology. 2019 May 1:282():7-15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.073. Epub 2018 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 30527992]

Miller TD, Askew JW, Anavekar NS. Noninvasive Stress Testing for Coronary Artery Disease. Heart failure clinics. 2016 Jan:12(1):65-82. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2015.08.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26567975]

Miller TD, Askew JW, Anavekar NS. Noninvasive stress testing for coronary artery disease. Cardiology clinics. 2014 Aug:32(3):387-404. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2014.04.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25091965]

Garner KK, Pomeroy W, Arnold JJ. Exercise Stress Testing: Indications and Common Questions. American family physician. 2017 Sep 1:96(5):293-299 [PubMed PMID: 28925651]

Magne J, Lancellotti P, Piérard LA. Exercise testing in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2014 Feb:7(2):188-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24524744]

Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Maron MS. Role of Exercise Testing in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2017 Nov:10(11):1374-1386. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.07.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29122139]

Argulian E, Chaudhry FA. Stress testing in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2012 May-Jun:54(6):477-82. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.04.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22687588]

Banerjee A, Newman DR, Van den Bruel A, Heneghan C. Diagnostic accuracy of exercise stress testing for coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. International journal of clinical practice. 2012 May:66(5):477-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02900.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22512607]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBires AM, Lawson D, Wasser TE, Raber-Baer D. Comparison of Bruce treadmill exercise test protocols: is ramped Bruce equal or superior to standard bruce in producing clinically valid studies for patients presenting for evaluation of cardiac ischemia or arrhythmia with body mass index equal to or greater than 30? Journal of nuclear medicine technology. 2013 Dec:41(4):274-8. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.113.124727. Epub 2013 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 24221922]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSharman JE, LaGerche A. Exercise blood pressure: clinical relevance and correct measurement. Journal of human hypertension. 2015 Jun:29(6):351-8. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2014.84. Epub 2014 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 25273859]

Fletcher GF, Ades PA, Kligfield P, Arena R, Balady GJ, Bittner VA, Coke LA, Fleg JL, Forman DE, Gerber TC, Gulati M, Madan K, Rhodes J, Thompson PD, Williams MA, American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013 Aug 20:128(8):873-934. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829b5b44. Epub 2013 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 23877260]

Günaydın ZY, Bektaş O, Gürel YE, Karagöz A, Kaya A, Kırış T, Zeren G, Yazıcı S. The value of the Duke treadmill score in predicting the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. Kardiologia polska. 2016:74(2):127-34. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2015.0143. Epub 2015 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 26202537]

Davila CD, Udelson JE. Trials and Tribulations of Assessing New Imaging Protocols: Combining Vasodilator Stress With Exercise. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2018 Mar:11(3):494-504. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.12.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29519339]

Haile L, Goss FL, Andreacci JL, Nagle EF, Robertson RJ. Affective and metabolic responses to self-selected intensity cycle exercise in young men. Physiology & behavior. 2019 Jun 1:205():9-14. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.02.012. Epub 2019 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 30763596]

Ghosh RM, Gates GJ, Walsh CA, Schiller MS, Pass RH, Ceresnak SR. The prevalence of arrhythmias, predictors for arrhythmias, and safety of exercise stress testing in children. Pediatric cardiology. 2015 Mar:36(3):584-90. doi: 10.1007/s00246-014-1053-9. Epub 2014 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 25384613]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZellweger MJ. Risk stratification in coronary artery disease: a patient-tailored approach over the ischaemic cascade. Swiss medical weekly. 2019 Feb 11:149():w20014. doi: 10.4414/smw.2019.20014. Epub 2019 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 30741398]

Wicks JR, Oldridge NB. How Accurate Is the Prediction of Maximal Oxygen Uptake with Treadmill Testing? PloS one. 2016:11(11):e0166608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166608. Epub 2016 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 27875547]