Introduction

Temporal mandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation, or mandibular dislocation, can present as bilateral or unilateral displacement of the mandibular condyle from the articular surface of the temporal bone (the glenoid fossa). Anterior, posterior, superior, and lateral mandibular dislocations can occur. The anatomy of the TMJ is important to understand for the evaluation and treatment of the condition. The mandibular condyle is normally in its position in the glenoid fossa of the temporal bone. The joint is one of the few joints in the body with a dense fibrocartilagenous disc that lies between the glenoid fossa and the condyle; this allows the joint to function as both a hinge and as a gliding joint. The muscles which participate in jaw closure are the masseter, medial pterygoid, and temporalis muscles. Jaw opening is the function of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Ligaments that support the joint are the temporomandibular, sphenomandibular, and capsular ligaments. Blood is supplied to the joint by the superficial temporal branch of the external carotid artery. The joint receives sensory innervation from the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (V3) via the masseteric and auriculotemporal nerves.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Temporal mandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation can occur as a result of atraumatic etiologies or trauma to the mandible. Factors leading to atraumatic dislocation can include anything that results in forceful, over-opening of the jaw, such as yawning, seizures, or repeated mastication, as well as underlying anatomic causes such as ligamentous laxity, aberrant anatomy, or connective tissue disorders. Atraumatic causes can include very ordinary daily activities like laughing, yawning, singing, vomiting, kissing.[1][2][3][4] Dystonic reactions (e.g., tetanus) and extrapyramidal side effects are also possible atraumatic causes.[5] Iatrogenic causes include dental treatments, endotracheal intubation, bronchoscopy, and laryngoscopy.[1][2][6][7][8] Acute facial trauma is one of the most common causes of dislocation.[9][10][11][2]

Risk factors for TMJ dislocation are important in identifying possible causes of the dislocation and the risk of recurrence. Risk factors include previous dislocation, structural or anatomic deficits, connective tissue disorders that affect stability (e.g., Marfan syndrome, Ehler-Danlos syndrome, muscular dystrophy, orofacial dystrophy), neurodegenerative or neurodysfunctional disorders (e.g., Huntington disease, multiple sclerosis or epilepsy), increasing age, and changes in the patient's dentition.[1][2][12]

Epidemiology

Mandibular dislocation is rare, and there is no overall gender or age-related predilection. As facial trauma is more prevalent overall in men, traumatic causes may show a slight male predilection. Anterior dislocations are the most common type of mandibular dislocation, usually secondary to atraumatic causes. Posterior, lateral, and superior dislocations are much rarer. Bilateral TMJ dislocations occur more often than unilateral dislocation.[13]

Pathophysiology

Mandible dislocation can occur anterior, posterior, superior, or lateral to the articular eminence. Dislocations can also be classified as acute, chronic, or recurrent.

Anterior dislocations are the most common type of dislocation. The condyle of the mandible is displaced anterior to the temporal bone articular eminence; this can occur by elevation of the mandible by the temporalis and masseter muscles before relaxation occurs by the lateral pterygoid. Anterior temporal mandibular joint (TMJ) dislocations often result following atraumatic causes that result in over-opening of the mandible or interruption of normal mouth opening. Anterior dislocation may increase the risk of recurrent dislocation.

A posterior dislocation often occurs as a result of a direct blow to the jaw, pushing the mandibular condyle posterior in the direction of the mastoid. Patients can have an injury to the external auditory canal from this type of injury, including temporary or permanent canal narrowing.

Lateral dislocations often present in the setting of a mandibular fracture.[10][11] The condyle can dislocate laterally relative to the fossa (type I, subluxation), or the condyle can dislocate laterally then superiorly and into the temporal fossa beyond the zygomatic arch (type II, luxation).[11]

Superior dislocation or central dislocation results from a direct blow to a partially open mouth causing upward migration of the condyle of the mandible. This mechanism can cause fracture of the glenoid fossa and dislocation of the mandibular condyle into the middle skull base, particularly in extremely high-velocity traumas such as motor vehicle accidents, but can be seen in assaults with blunt weapons also. Other injuries can occur, including injuries to the facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve), vestibulocochlear nerve (eighth cranial nerve), intracranial hematoma, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and cerebral contusion. Superior dislocation has correlations with deafness, facial nerve palsy, meningitis, and cerebral contusion.[14][9]

Acute dislocation is usually an isolated event and often occurs due to facial trauma, or over-opening of the mouth. Examples include yawning, laughing, singing, vomiting or seizures, or iatrogenic causes such as intubation, endoscopic procedures, or dental procedures. This can often be treated with closed reduction, though may require anesthesia or muscle relaxants.

Generally, chronic dislocation is dislocation lasting longer than 72 hours, but no definitive consensus exists. This type of injury occurs resulting from untreated mandible dislocation and typically requires open reduction.[15][16][17]

Recurrent dislocations are repeated, acute, or chronic dislocation, which typically occurs due to hypermobility of the joint secondary to hypermobility syndromes, shallow mandibular fossa, or joint capsule laxity.[16]

Common findings when assessing the patient's history and physical exam include symptoms such as inability to close the mouth, drooling, difficulty with speech and chewing, severe preauricular pain, and signs including garbled speech, palpable preauricular depression.[3][18]

History and Physical

In acute dislocation, patients will often present with pain in the preauricular area, difficulty closing the mouth, which may lead to garbled speech and drooling. Assessment questions about an inciting event such as trauma, yawning, laughing, vomiting, seizures, or iatrogenic cause (dental work, intubation, endoscopy) should be documented. Ask about medication use (haloperidol, phenothiazines, and thiothixene have been associated with an increased risk of jaw dislocation). History of neurodegenerative or connective tissue disorders may also increase the risk of dislocation; examples include Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, Huntington disease, Parkinson disease, epilepsy.[1][2][12]

The physical exam may reveal tenderness over the preauricular area with palpable indentation at the location of the TMJ. Jaw deviation may be present, and the patient’s mouth will often be slightly open. The provider should examine the mandible for symmetry to determine if the dislocation is unilateral or bilateral. Bilateral dislocation will have a midline, open, fixed jaw. In unilateral dislocation, the jaw deviates to one side. In a superior dislocation, a bulge will often be present in the preauricular and temporal areas of the face.[19] The trigeminal nerve (fifth cranial nerve), facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve), and vestibulocochlear nerve (eighth cranial nerve) should undergo testing in superior dislocations as damage to these nerves can occur.

Evaluation

Diagnosis of mandibular dislocation is typically possible with history and physical. Imaging may not be necessary for the diagnosis of a mandibular dislocation. For traumatic, unclear diagnosis, or concern for fracture, the imaging test of choice is a computed tomography (CT) scan. A CT scan is useful for the assessment of the type of dislocation and associated fractures. X-rays and panoramic jaw radiographs can also be useful, however, there may be some limitations due to overlapping spine projections in the posteroanterior (PA) view. Imaging should be performed before reduction to assess for fracture. MRI can also be used to assess the joint capsule and surrounding ligaments. Typically MRI is reserved for chronic recurrent dislocations or complications, including assessment for ischemic necrosis, osteomyelitis, or pseudoarthrosis. Adults with dislocation secondary to atraumatic cause and no concern for fracture on the physical exam have reduction without imaging.[20][21][20] Imaging is necessary following reduction as an iatrogenic fracture can occur following the forceful manipulation of the mandible required to reduce the dislocation.

No initial laboratory testing is necessary for isolated TMJ dislocation. Women of childbearing age should have a pregnancy test performed before performing imaging.

Treatment / Management

Before arrival in the hospital, there are no established universal protocols for prehospital care of mandibular dislocation. The basis for a transport decision is on patient stability and other factors that may have contributed to the injury, for example, trauma, shock, or altered mental status. So long as the patient has no airway symptoms, transport can proceed.

In the emergency department, consider ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) upon initial presentation. Stabilizing the patient’s life-threatening conditions should take priority in the initial workup. History and physical should include a thorough history, including risk factors for TMJ dislocation. If physical exam and imaging are concerning for fracture or chronic dislocation, consultation to oral maxillofacial surgery or otolaryngology may be appropriate. Severe fractures, chronic dislocations, or patients with concomitant injuries may necessitate open reduction performed in the operating room (OR).[20]

Anesthesia or sedation should be performed to reduce the patient's pain and anxiety. Benzodiazepines such as midazolam and fentanyl are the recommended agents. Intravenous propofol bolus is a useful agent for TMJ reduction. It is commonly used for sedation and has a short half-life and anti-emetic effects.[22] Local infiltration of anesthetic and nerve block is also an option before reduction. Lidocaine can be injected directly into the preauricular depression. Peripheral nerve block of the masseter and deep temporal nerve along with infiltration of the TMJ capsule can be performed, allowing for minimally painful reduction by decreasing muscle spasm and pain. The use of a nerve block is possible in conjunction with or independently from the use of sedation or general anesthesia.[23](B3)

Reduction techniques include intraoral techniques and extraoral techniques. Intraoral techniques include the bimanual, wrist pivot, and recumbent position. Extraoral techniques protect the provider's fingers from being bitten. Extraoral techniques include the gag reflex method, the syringe method, and the external approach.

The materials involved in all intraoral reduction techniques include gloves, a bite block, Yankauer suction, and MacGill forceps. Rolled gauze and tongue depressors can be used to protect the provider's thumbs.

Bimanual Method: also known as the classic, traditional, or Hippocratic intraoral reduction method, which is the most common technique used for TMJ reduction. The provider stands directly in front of the seated patient, facing toward the patient. An assistant should stabilize the head throughout the procedure. While wearing gloves, the provider places both thumbs into the patient's open mouth. Thumbs may be wrapped in gauze for protection. Each thumb gets placed on the patient’s respective lower molars or the external oblique ridge as far back as possible. The provider’s fingers are placed out of the mouth on the angle of the mandible to elevate the body of the mandible and chin. The pressure is applied by the thumbs to push the mandible downward and then backward while maintaining the mouth slightly open. The goal is to free the condyle from the anterior eminence and push the mandible back into the temporal fossa.[2]

Wrist Pivot Method: It is an alternative method that uses the same materials as the bimanual intraoral technique. The provider faces the seated patient. An assistant should stabilize the patient's head during the reduction. With gloved hands, the thumbs of the provider are placed out of the mouth under the mentum (chin), pointing toward the midline. The index and middle fingers get positioned on the bilateral lower molars. The thumbs apply upward pressure with equal downward pressure by the fingers. The wrist is then pivoted forward, causing the angle of the mandible to move downward and posterior, reducing the dislocation.[24](B3)

Recumbent (or Supine) Technique: In this technique, the provider stands or sits behind the patient while the patient is in a supine position. The patient's head is braced against the provider’s abdomen. While wearing gloves, the provider’s thumbs are placed on the lower molars. The fingers of the provider’s hands are out of the mouth and used to grip the angle of the mandible. Downward then backward pressure is applied by the thumbs to free the condyle from the anterior eminence and guide the condyle into the temporal fossa.

Gag Reflex Method: It is a technique in which the provider's fingers do not enter the patient's mouth, thereby protecting the provider's fingers from biting. This technique is performed by using a mouth mirror to stimulate the gag reflex by touching the patient’s soft palate and pharynx; this will trigger the depressor and protrude muscles, which may flex and relocate the mandibular condyle into the temporal fossa.[1][2] This technique is discouraged as there is an increased risk of vomiting and aspiration when stimulating the gag reflex.

Syringe Method: This is performed by placing an empty 5 or 10 mL syringe, oriented transversely, on one side in the posterior portion of the patient's mouth, between the upper and lower molars or posterior gums. The patient is directed to bite down softly and roll the syringe backward and forward. This maneuver gets repeated until the mandible reduces on that side. The opposite side can reduce spontaneously; however, if it does not, the syringe can be placed on the opposite side of the mouth, and the technique repeated. Syringe size is chosen based on which size can fit most easily. Procedural sedation or anesthesia is not a requirement for this technique.[25]

External Approach: It is performed by placing the patient in a seated position with the provider facing the patient. The provider places the fingers of one hand on the ascending ramus, grasping the mandibular angle. Thumb placement is on the malar eminence of the maxilla or zygomatic bone. The opposite side is positioned using the thumb above the displaced coronoid process, applying posterior pressure. The fingers of the same hand pull traction on the mastoid process of the temporal bone. The simultaneous action of both hands is performed to reduce the mandible. The angle of the mandible is pulled anteriorly while on the opposite side, the coronoid process is pushed posteriorly and directed into the temporal fossa. One side of the mandible will reduce. If the opposite side does not reduce spontaneously immediately following the first reduction, reverse hand positions and reduce the second side.[26](B3)

Dislocations that require emergent consultation to otolaryngology or oral maxillofacial surgery include chronic dislocation, superior or posterior dislocation, fracture-dislocation, open dislocation, cranial nerve injury associated with a dislocation, recurrent or history of two or more prior dislocations, or dislocation that is nonreducible following multiple attempts using closed reduction technique.

Subspecialists can perform conservative management following recurrent dislocation. Examples of conservative management include botulinum toxin injections, autologous blood injections, physiotherapy, soft diets, mandibular range of motion restriction, local anesthesia.[27][2][1](A1)

Botulinum Toxin A Injection: This can be used with other techniques or as primary therapy. Twenty-five to fifty units of botulinum toxin A is injected directly into the lateral pterygoid to prevent recurrent dislocation. Injections can be repeated every 3 to 6 months to improve outcomes and reduce morbidity.[1][12] The mechanism of action blocks the release of acetylcholine of the neuromuscular junction by blocking the calcium-mediated release. The result of blocking the release of acetylcholine is a temporary weakening of the muscle. The use of the toxin has been reported to be a reasonable, safe treatment option for use in the pediatric population with recurrent TMJ dislocation.[28](B3)

Autologous Blood Injection: This is a conservative technique in which the joint space receives an injection with the patient's whole blood. In this technique, the joint space is lavaged with crystalloid fluid and drained. Whole blood is then drawn from the patient and injected into the joint space. The volume of blood injected is approximately 2 to 4 mL into the joint space and 1 to 1.5 mL into the pericapsular structures. The goal of injecting autologous blood into the joint space is to cause an inflammatory reaction resulting in fibrosis and scarring of the joint and capsular tissue. This process will decrease compliance of the joint and decreased range of motion. There are reports regarding concerns about damage to the joint cartilage secondary to the inflammatory reaction using this technique.[27][2][1](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Mandible fracture and mandible condylar fracture are important to recognize early; they may occur in conjunction with mandibular dislocation. In patients with dislocation secondary to trauma, imaging should be performed to assess for fracture. Infections that may appear similar to TMJ dislocation can include epiglottitis, retropharyngeal abscess, or peritonsillar abscess. These infectious presentations can have similar clinical features to mandibular dislocation, including drooling, trismus, and throat or neck pain. It is important to evaluate the oropharynx and obtain an appropriate history from the patient as the treatment for infection and dislocation differ vastly. TMJ dysfunction or acute closed locking of the TMJ meniscus and dystonic reaction such as tetanus can be mistaken for dislocation as the patient will not be able to open their mouth normally. History, physical exam, and imaging are important for differentiating between the features of each disease from mandibular dislocation.

Prognosis

The prognosis of isolated mandibular dislocation is good but differs on the type of dislocation. Anterior dislocations have an excellent prognosis while lateral dislocations are mostly associated with fractures and require open reduction. Long-term complications are rare following appropriate management of acute dislocation. Despite proper treatment, some acute dislocations will have an increased risk of recurrence.[2]

Complications

Recurrent and chronic mandible dislocation may occur. Also, recurrent dislocation can damage joint ligaments and joint capsule and lead to degenerative joint disease. The external auditory canal can be damaged from both posterior and superior dislocation and may result in deafness. Nerve damage can occur to the facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve) or vestibulocochlear nerve (eighth cranial nerve). Injury to blood vessels can result in damage to the external carotid artery or lead to cerebral contusion.

Iatrogenic complications may also occur following reduction. A fracture may occur as a result of the force applied to the mandible. Ligamentous injury or avulsion fracture may occur as a result of forceful manipulation.[29]

Complications of botulinum toxin injection include hemorrhage, intravascular injection, diffusion into nearby tissue, dysphagia, toxin-induced velopharyngeal insufficiency. Botulinum toxin should be avoided in patients with an allergy to botulinum toxin and myasthenia gravis.[1][12]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients can generally be discharged following successful, uncomplicated reduction. In the post-reduction period, patients should be placed in a head-chin bandage or a rigid cervical collar to prevent an immediate recurrence. Patients should be advised not to open their mouth widely (greater than 2 cm) for one to three weeks post-reduction. The patient should be limited to a soft mechanical diet for a few days to up to two weeks. Care should be taken to support the jaw when yawning. Using a padded rigid cervical collar may add support and prevent wide jaw opening. To decrease the pain and swelling associated with dislocation-reduction non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are an option. The patient should receive instructions to follow up with an otolaryngologist (ENT) or oral maxillofacial surgeon (OMFS) within two to three days.[2][30]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The reduction of a mandible dislocation is a procedure that can be associated with complications and costs. A common complication is a recurrent dislocation resulting in patient discomfort, emergency department visits, and an increased cost to the healthcare system.[2] It is essential to incorporate the healthcare team in all aspects of the patient’s care. A team approach is an ideal way to limit the morbidity involved with this procedure. During the patient’s care, the following should take place:[29]

- An evaluation by an emergency medicine provider to assess for dislocation and associated fractures

- Imaging read by a radiologist before and after the reduction

- Review of procedural and post-reduction medications by a pharmacist for adverse interactions with the patient’s medications

- Patient instructions by a nurse concerning the elements of a soft-mechanical diet

- Evaluation by a specialist, e.g., an otolaryngologist or oral maxillofacial surgeon, for the management of recurrent, chronic, or traumatic dislocation

- Specialty-trained orthopedic nursing care at all steps of the diagnosis and management process, irrespective of what course the treatment takes, from conservative measures to surgery

An interprofessional team approach to the management of the patient during all aspects of the patient’s care helps the patient to have expert treatment resulting in the best possible outcome. [Level IV]

Media

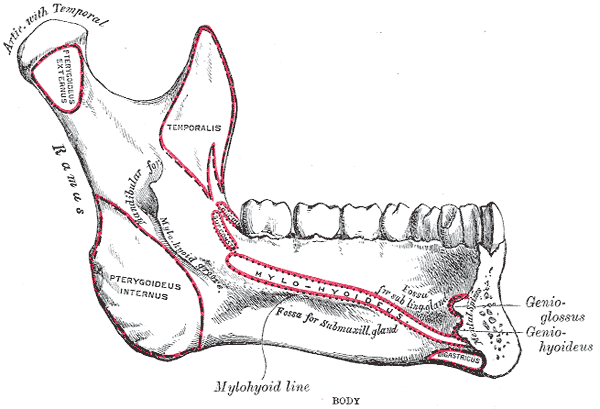

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Side View of the Mandible, Interior View, Lower Jaw.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Sharma NK, Singh AK, Pandey A, Verma V, Singh S. Temporomandibular joint dislocation. National journal of maxillofacial surgery. 2015 Jan-Jun:6(1):16-20. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.168212. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26668447]

Liddell A, Perez DE. Temporomandibular joint dislocation. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2015 Feb:27(1):125-36. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2014.09.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25483448]

Shorey CW, Campbell JH. Dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2000 Jun:89(6):662-8 [PubMed PMID: 10846117]

Whiteman PJ, Pradel EC. Bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation in a 10-month-old infant after vomiting. Pediatric emergency care. 2000 Dec:16(6):418-9 [PubMed PMID: 11138886]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThachil RT, Philip B, Sridhar CB. Temporomandibular dislocation: a complication of tetanus. The Journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1993 Feb:96(1):60-1 [PubMed PMID: 8429577]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGambling DR, Ross PL. Temporomandibular joint subluxation on induction of anesthesia. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1988 Jan:67(1):91-2 [PubMed PMID: 3337354]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLacy PD, Lee JM, O'Morain CA. Temporomandibular joint dislocation: an unusual complication of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2000 Dec:95(12):3653-4 [PubMed PMID: 11151916]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMangi Q, Ridgway PF, Ibrahim Z, Evoy D. Dislocation of the mandible. Surgical endoscopy. 2004 Mar:18(3):554-6 [PubMed PMID: 15114987]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHarstall R, Gratz KW, Zwahlen RA. Mandibular condyle dislocation into the middle cranial fossa: a case report and review of literature. The Journal of trauma. 2005 Dec:59(6):1495-503 [PubMed PMID: 16394930]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOhura N, Ichioka S, Sudo T, Nakagawa M, Kumaido K, Nakatsuka T. Dislocation of the bilateral mandibular condyle into the middle cranial fossa: review of the literature and clinical experience. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2006 Jul:64(7):1165-72 [PubMed PMID: 16781355]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchwab RA, Genners K, Robinson WA. Clinical predictors of mandibular fractures. The American journal of emergency medicine. 1998 May:16(3):304-5 [PubMed PMID: 9596439]

Martins WD, Ribas Mde O, Bisinelli J, França BH, Martins G. Recurrent dislocation of the temporomandibular joint: a literature review and two case reports treated with eminectomy. Cranio : the journal of craniomandibular practice. 2014 Apr:32(2):110-7 [PubMed PMID: 24839722]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePrechel U, Ottl P, Ahlers OM, Neff A. The Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2018 Feb 2:115(5):59-64. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0059. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29439762]

Akinbami BO. Evaluation of the mechanism and principles of management of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Systematic review of literature and a proposed new classification of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Head & face medicine. 2011 Jun 15:7():10. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-7-10. Epub 2011 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 21676208]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHoard MA, Tadje JP, Gampper TJ, Edlich RF. Traumatic chronic TMJ dislocation: report of an unusual case and discussion of management. The Journal of cranio-maxillofacial trauma. 1998 Winter:4(4):44-7 [PubMed PMID: 11951281]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOzcelik TB, Pektas ZO. Management of chronic unilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation with a mandibular guidance prosthesis: a clinical report. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 2008 Feb:99(2):95-100. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(08)60024-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18262009]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUndt G, Kermer C, Piehslinger E, Rasse M. Treatment of recurrent mandibular dislocation, Part I: Leclerc blocking procedure. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 1997 Apr:26(2):92-7 [PubMed PMID: 9151160]

Lovely FW, Copeland RA. Reduction eminoplasty for chronic recurrent luxation of the temporomandibular joint. Journal (Canadian Dental Association). 1981 Mar:47(3):179-84 [PubMed PMID: 7013948]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSharma D, Khasgiwala A, Maheshwari B, Singh C, Shakya N. Superolateral dislocation of an intact mandibular condyle into the temporal fossa: case report and literature review. Dental traumatology : official publication of International Association for Dental Traumatology. 2017 Feb:33(1):64-70. doi: 10.1111/edt.12282. Epub 2016 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 27207395]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZweifel DF, Pietramaggiori G, Broome M. Videos in clinical medicine. Repositioning dislocated temporomandibular joints. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Feb 6:370(6):e9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm1301200. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24499237]

Schuknecht B, Graetz K. Radiologic assessment of maxillofacial, mandibular, and skull base trauma. European radiology. 2005 Mar:15(3):560-8 [PubMed PMID: 15662492]

Totten VY, Zambito RF. Propofol bolus facilitates reduction of luxed temporomandibular joints. The Journal of emergency medicine. 1998 May-Jun:16(3):467-70 [PubMed PMID: 9610979]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYoung AL, Khan J, Thomas DC, Quek SY. Use of masseteric and deep temporal nerve blocks for reduction of mandibular dislocation. Anesthesia progress. 2009 Spring:56(1):9-13. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-56.1.9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19562887]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLowery LE, Beeson MS, Lum KK. The wrist pivot method, a novel technique for temporomandibular joint reduction. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2004 Aug:27(2):167-70 [PubMed PMID: 15261360]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGorchynski J, Karabidian E, Sanchez M. The "syringe" technique: a hands-free approach for the reduction of acute nontraumatic temporomandibular dislocations in the emergency department. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2014 Dec:47(6):676-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.06.050. Epub 2014 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 25278137]

Chen YC, Chen CT, Lin CH, Chen YR. A safe and effective way for reduction of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Annals of plastic surgery. 2007 Jan:58(1):105-8 [PubMed PMID: 17197953]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVaredi P, Bohluli B. Autologous blood injection for treatment of chronic recurrent TMJ dislocation: is it successful? Is it safe enough? A systematic review. Oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2015 Sep:19(3):243-52. doi: 10.1007/s10006-015-0500-y. Epub 2015 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 25934244]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStark TR, Perez CV, Okeson JP. Recurrent TMJ Dislocation Managed with Botulinum Toxin Type A Injections in a Pediatric Patient. Pediatric dentistry. 2015 Jan-Feb:37(1):65-9 [PubMed PMID: 25685976]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChhabra S, Chhabra N, Gupta P Jr. Recurrent Mandibular Dislocation in Geriatric Patients: Treatment and Prevention by a Simple and Non-invasive Technique. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery. 2015 Mar:14(Suppl 1):231-4. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0454-7. Epub 2013 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 25838702]

Jaisani MR, Pradhan L, Sagtani A. Use of cervical collar in temporomandibular dislocation. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery. 2015 Jun:14(2):470-1. doi: 10.1007/s12663-013-0505-8. Epub 2013 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 26028876]