Introduction

Managing patients on anticoagulation and anti-aggregation therapy is a daily challenge for physicians. The interruption of therapy can increase the risk of thrombotic events during and after surgery. However, the non-interruption of these medications can heighten the risk of bleeding during surgery and trigger a sequence of undesirable outcomes ranging from minor to uncontrolled bleeding. The optimal management of these patients is thus achieved through a balance between thromboembolic and bleeding risks. Several case-based considerations affect whether or not to interrupt anticoagulation or anti-aggregation therapy before surgery. These include evaluating an individual's underlying bleeding risk, the risk of bleeding associated with the surgical procedure, the timing of interruption and resumption of anticoagulation therapy, and whether to use bridging therapy. These are all typical questions that can be addressed in this topic.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Anticoagulation therapy is most commonly indicated in the presence of atrial fibrillation, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and after placement of prosthetic heart valves. Patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary interventions are typically on dual antithrombotic therapy, and patients with a past medical history of stroke, coronary artery by-pass grafting, and essential thrombocytosis could require antithrombotic therapy.

Epidemiology

Atrial fibrillation, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism are the leading causes of anticoagulation treatment. In the United States alone, approximately 3 to 5 million people suffer from atrial fibrillation, and this number is expected to increase to 8 million by 2050.[1] Likewise, approximately 250,000 patients annually in the United States require anticoagulation therapy cessation to be considered for surgery.[2]

Pathophysiology

The process of physiologic hemostasis can be altered for several reasons, such as genetic disorders, malignancy, sepsis, surgery, and drugs (those used for anti-aggregation and anticoagulation). A pharmacological review of anticoagulation is essential from a basic approach to perioperative anticoagulation.

Aspirin (Acetylsalicylic Acid)

This agent is the most commonly prescribed antiplatelet drug to prevent cardiovascular disorders. Its mechanism of action is the irreversible inhibition of the cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 and 2 enzymes. The action of COX is necessary for the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin (PG) H2. The PGH2 is rapidly converted to several bioactive prostanoids, including thromboxane A2, a potent vasoconstrictor and an inductor of platelet aggregation. Despite the short half-life of aspirin (3 to 6 hours), its irreversible effects last for the complete lifetime of the platelet (8 to 9 days). After the aspirin therapy interruption, platelet function recovery depends on its turnover (approximately 10% per day).[3][4]

Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

These drugs act by inhibiting COX enzymes, depending on the drug. Some NSAIDs can selectively inhibit the COX 2 enzyme that mediates pain and inflammation, simultaneously limiting the undesirable effects of COX 1 inhibition. The effect of NSAIDs on platelet function is considered a short-term effect that normalizes within 3 days; nonetheless, this can vary between drugs in the class. For short-acting drugs like ibuprofen, diclofenac, and indomethacin, 50% of platelet function is restored 6 hours after the last dose and normalized after 24 hours.[4][5]

Thienopyridines (Clopidogrel and Prasugrel)

In platelets, these are inhibitors of the adenosine diphosphate receptor, also called the P2Y12 receptor. Physiologically, the union of adenosine diphosphate with its receptor increases intracellular calcium levels and activates the GpIIB/IIIa platelet receptor that promotes the stabilization of the platelet clot through fibrinogen bonds.[6] Clopidogrel and prasugrel are prodrugs in which active metabolites irreversibly affect the platelet function in a time- and dose-dependent fashion. A clopidogrel dose of 75 mg daily produces a 60% decrease in platelet function in 3 to 5 days; in contrast, a 600 mg loading dose can achieve a steady-state platelet inhibition in 6 to 8 hours.[3] In the same way, a loading dose of prasugrel of 60 mg is enough to produce steady-state platelet inhibition 2 hours after drug administration. Due to the irreversible mechanism of action, it is recommended to interrupt these drugs 5 to 7 days before non-cardiac elective surgery.[4]

Non-thienopyridines (Ticagrelor and Cangrelor)

These drugs are relatively new and have different mechanisms of action from those discussed thus far. Ticagrelor is a reversible, non-competitive ATP analog that binds to a G-protein in the P2Y12 receptor, preventing its activation and signaling. After a loading dose of ticagrelor, the maximum antiplatelet effect is achieved within 2 hours, plasma half-life is 8 to 12 hours, and steady-state concentration in 2 to 3 days. Due to the reversible effect of ticagrelor on platelets, it is recommended to be suspended 5 days before surgery.[4] On the other hand, cangrelor is a direct, reversible, and intravenously administered drug that inhibits the P2Y12 receptor. Cangrelor can inhibit 95% to 100% of platelet activity within the first 2 minutes of administration; the plasma half-life of cangrelor (3 to 6 minutes) allows recovery of 80% to 90% platelet function within 60 to 90 minutes of discontinuing the intravenous infusion.[7]

Vitamin K Antagonists (Warfarin, Acenocoumarol, Phenprocoumon)

These are also called coumarins. The most recognized and widely used drug of this group is warfarin, which has been available for more than 50 years. The mechanism of action of warfarin is the inhibition of the 2,3 epoxide reductase enzyme, responsible for the cyclical conversion of oxidized vitamin K to a reduced state. The latter is necessary as a cofactor for the carboxylation of glutamic acid at the N-terminus of coagulation factors. Clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X cannot bind to the divalent calcium necessary for normal activation without gamma carboxyglutamate residues. However, the inhibition of carboxylation also affects the production of protein C and S anticoagulants. This creates a transient procoagulant state that can be explained by the shorter half-life of these anticoagulants (8 and 30 hours), compared to factor II and factor X (60 and 72 hours). This phenomenon is more frequent with higher doses of vitamin K antagonists at the beginning of anticoagulation therapy.[8] Warfarin is a racemic mixture of the R and S stereoisomers of the drug; the S isomer is 3-5 times more potent than the R isomer. The half-life of warfarin is 36 to 42 hours (S isomer 29 hours, R isomer 45 hours); nonetheless, it can be altered by several factors. In practice, warfarin is a drug of difficult titration due to the high number of pharmacological interactions and genetic variations that can affect its metabolism.[9]

Direct Inhibitors of Factor Xa (Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, Edoxaban, Betrixaban)

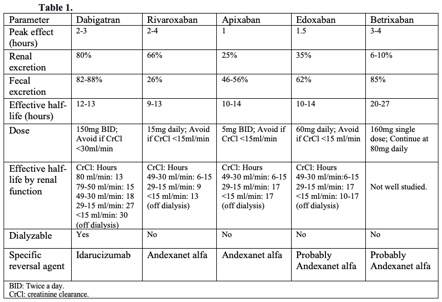

The common mechanism of action of these drugs, also known as direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), is to bind to the active site of factor Xa, thus inactivating it. Factor Xa is considered the rate-limiting step for the progression of the coagulation cascade, thrombin activation, and, ultimately, clot formation.[10] Some advantages of prescribing DOACs are their short half-life and rapid onset of action, allowing for an easier interruption and re-initiation of anticoagulation therapy after surgery. Furthermore, it seems that the direct inhibitors of factor Xa have a lower bleeding risk compared to vitamin K antagonists, making routine coagulation tests unnecessary.[11] However, the pharmacokinetic properties of each DOAC can vary according to the renal and liver function of the patient (see Table. Pharmacological Characteristics of Direct Oral Anticoagulation DOACs Drugs).

Direct Inhibitors of Thrombin

Dabigatran is the only medication in this group. Its mechanism of action is the direct inhibition of thrombin, preventing the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin and, thus, clot formation. Dabigatran has a quick onset of action (0.5 to 2 hours) and is metabolized by non-specific plasma esterases. The plasma half-life is around 12 hours; however, the half-life of this drug is tremendously affected by renal function, as its excretion is 80% by the kidneys and less than 10% by the liver. It is recommended to avoid dabigatran use with creatinine clearance (CrCl) less than 30ml/min due to the potential for drug accumulation and adverse effects of bleeding (see Table. Pharmacological Characteristics of Direct Oral Anticoagulation DOACs Drugs).

Fondaparinux

This drug is a pentasaccharide that acts as an indirect factor Xa inhibitor. The exact mechanism of action is the reversible binding of the drug to the antithrombin factor, potentiating its activity to inactivate Factor Xa. The plasma half-life of fondaparinux is approximately 15 to 17 hours. Its anticoagulant activity persists even 2 to 4 days after the last dose of the drug in a person with normal renal function.[11]

Heparins

The binding of the heparin molecule to the antithrombin receptor enhances its potency to inactivate factors II and Xa. This drug has been widely used for years, with multiple indications and dosages. One of this pharmacological group's most concerning adverse effects is the possibility of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Fortunately, this complication is infrequent, though it depends on the dose, route of administration, and type of heparin. In patients with renal failure and a CrCl < 30 ml/min, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) should be avoided or adjusted to renal function. The use of unfractionated heparin (UFH) is a suitable option in this case. Heparin can be administered as a therapeutic dose for patients with high thromboembolic risk (enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily or dalteparin 100 units/kg twice daily) or as the prophylactic dose for patients undergoing bridge therapy (enoxaparin 40 mg once daily or dalteparin 5,000 units once daily).[12]

Evaluation

The approach recommended by several well-known guidelines is based on 4 considerations that aim to guide the physician in elective surgery cases.[13]

Determine the Thromboembolic Risk of the Patient

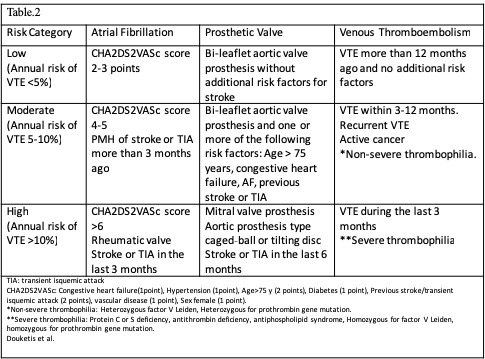

The 3 major conditions related to a higher risk of thromboembolic events are atrial fibrillation, prosthetic heart valves, and recent thromboembolism (venous or arterial). The thromboembolic risk can be estimated through clinical variables in the case of atrial fibrillation with the CHA2DS2VASc score.[14] The localization, type of valve, number of prosthetic valves, and associated cardiac risk factors lead to the risk stratification of patients with prosthetic valves. Regarding thromboembolism, the time after the episode and the risk of recurrence determine risk categorization. The venous thromboembolism (VTE) can be classified as provoked (higher risk of recurrence) when an inciting event is identifiable or unprovoked when a cause is non-identifiable. An example of provoked VTE is a patient with permanent risk factors such as congestive heart failure, malignancy, inherited thrombophilia, or inflammatory bowel disease (see Table. Thrombotic Risk Stratification).[15]

Determine the Procedural Bleeding Risk

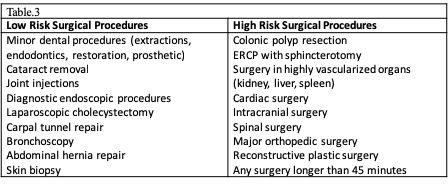

When evaluating bleeding risk, it is imperative to consider the type of surgery and clinical characteristics of the patient. These characteristics are assessed with the HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal liver or kidney function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile International Normalized Ratio [INR], elderly, drugs, alcohol) score. Each positive item earns 1 point, and a HAS-BLED score > 3 indicates a high bleeding risk. The BNK Online Bridging Registry (BORDER) study assessed the possible predictors of perioperative bleeding in patients undergoing invasive cardiac procedures. They found that the HAS-BLED score is a reliable predictor of perioperative bleeding (HR 11.8, 95% CI 5.6-24.9).[16] As a general guideline, the procedural risk can be divided into low risk (0-2% 2-day risk of major bleeding) or high risk (2% to 4% 2-day risk of major bleeding). Among the diversity of surgical procedures, intracranial, cardiac, and neuraxial procedures are of special concern due to the localization of potential bleeding and poor patient outcomes in this complication (see Table. Bleeding Bisk According to Type of Surgery).[17]

Determine Whether or Not Interrupt Anticoagulation or Antithrombotic TherapyThe right approach to this decision is the balance between risks and benefits of anticoagulation interruption. Clinical judgment is imperative, as there is no score or calculator to determine the classification of the patient straightforwardly. As a generalized consideration, patients with a high risk of bleeding benefit from anticoagulation interruption.[18][19][20] However, those patients with high thromboembolic risk might benefit from bridging therapy and the shortest period of anticoagulation withdrawal as possible. An example of this scenario is the patient undergoing potentially curative cancer surgery. In other scenarios, delaying the elective surgical procedure after a balance of risks and benefits is a suitable option. In patients with a recent episode of VTE (less than 1 month ago), the risk of recurrence in the subsequent month can be as high as 40%. An elective surgical procedure should be deferred up to 3 months after an episode of VTE, if possible. For patients with a recent acute ischemic stroke undergoing non-cardiac elective surgical procedures, the risk of having a major cardiovascular event after surgery is high, especially within the first 3 months. The American College of Surgeons recommends deferring the surgery up to 9 months in this scenario when the risk of cardiac events has plateaued after a stroke.[18]

Another common scenario is the patient with coronary stents, most of which are on dual anti-aggregation. Approximately 5% of these patients require surgery during the next year after coronary stent implantation. Suppose aspirin and thienopyridine need to be suspended during the perioperative period. In that case, the elective surgical procedure should be delayed 6 weeks for patients with bare-metal stents and 6 months for drug-eluting stents.[4][12] In case the elective surgery cannot be postponed, the dual anti-aggregation therapy should be continued throughout the perioperative period.[21][22] Despite limited evidence, there are scenarios where anticoagulation therapy continuation is preferable in patients with low bleeding risk. Dental procedures are considered low-bleeding-risk procedures. Most evidence comes from patients receiving warfarin with a therapeutic INR range. The studies conclude that continuing anticoagulation therapy is safe, not only in dental extraction but in other dental procedures, and that bridging therapy could be related to even more bleeding associated with these procedures.[23][24] One 4-year, cross-sectional study assessed bleeding risk in patients with DOACs, showing no significant bleeding association with continuing anticoagulation therapy.

Endovascular procedures (venous and arterial angioplasty, angiography, catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation, and atherectomy) studies were analyzed in a meta-analysis of 20,000 patients on warfarin anticoagulation.[25][26] The study concluded that rates of complications were low or equivalent between interrupted and uninterrupted warfarin anticoagulation groups. Similar findings have been published with DOACs. The first study was the VENTURE-AF (rivaroxaban vs. VKA in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing catheter ablation); the number of complications was low and similar between groups.[27] The RE-CIRCUIT study (dabigatran vs. warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing catheter ablation); dabigatran had lower rates of major bleeding than warfarin, and there was no difference in stroke or systemic embolism between groups.[28] Uninterrupted apixaban and edoxaban have also been shown to be safe in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing catheter ablation.

Implantation of prosthetic cardiac devices is also considered a bleeding risk procedure. Two studies, the BRUISE CONTROL 1 and 2, have addressed this scenario. The first study examined uninterrupted anticoagulation vs. warfarin interruption and a low therapeutic dose of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (1 mg per kg/twice daily of enoxaparin) in patients undergoing pacemaker implantation. The patients with uninterrupted warfarin had a lower incidence of pocket hematoma complications compared with the group that received bridging therapy with LMWH (3.5% vs. 16%, P <0.01).[29] The BRUISE CONTROL 2 study evaluated the safety of performing electrophysiologic device procedures without interrupting DOAC anticoagulation therapy. The study compared uninterrupted DOACs vs. interrupted DOACs (apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran interrupted 2 days before surgery) in patients with high thromboembolic risk. The strategy of continuing DOACs to reduce the complications of pocket hematoma was not superior to the interruption of DOACs 48 hours before the procedure.[30] Additionally, there was no statistically significant difference in other outcomes such as stroke, any hematoma, and any adverse event. This trial was terminated early due to futility.

Determine Whether or Not Bridging Anticoagulation

Bridging anticoagulation consists of the substitution of a long-acting anticoagulant (usually with warfarin) for a shorter-acting anticoagulant (usually LMWH) to limit the time of subtherapeutic anticoagulation levels and minimize thromboembolic risk[31]. Despite the growing evidence about the limited to nonexistent benefits of bridging therapy, it is still being used on a case-by-case basis. Clinical scenarios that may benefit from bridging therapy are those involving patients with high thromboembolic risk. In several guidelines, the following scenarios have been proposed:

- The patient with a mechanical heart valve: Mitral valve replacement, aortic valve replacement with additional risk factors (stroke, TIA, cardioembolic event, or intracardiac thrombus), more than 2 mechanical valves.

- Patients with stroke, episode of systemic emboli, or VTE during the last 3 months. Patients presenting with a thromboembolic event after interruption of chronic anticoagulation therapy or those presenting with VTE while on therapeutic anticoagulation.

- Patients with atrial fibrillation and CHA2DS2VASc score > 5 plus additional cardiovascular risk factors (rheumatic valve disease, stroke, or systemic embolism within the last 12 weeks). A CHA2DS2VASc score > 6 with or without additional risk factors.

- Patients with recent coronary stenting (within the previous 12 weeks)

Evidence on bridging therapy follows a trend against its use. Sigeal et al (2012) performed a meta-analysis of 34 studies, most of which were observational. Despite the criticism of this meta-analysis for its heterogeneity of studies, interesting conclusions were drawn. Regarding the risk of thromboembolism, there was no statistically significant difference between patients who received bridging therapy and those who did not receive bridging therapy(OR:0.80; 95% CI 0.42-1.54). However, the risk of major bleeding had a threefold increase in patients who received bridging therapy compared with patients who did not (OR: 3.60; 95% CI 1.52-8.50).[32] Large studies of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation, such as the RE-LY study (warfarin vs. dabigatran), showed that patients on warfarin who received bridging therapy had more thromboembolic events compared with those who did not receive bridging therapy (1.8 vs. 0.3%). Patients who received warfarin plus bridging therapy had a higher risk of major bleeding (warfarin plus bridging therapy 6.8%; warfarin without bridging 1.6%) compared with patients who received dabigatran plus bridging therapy (dabigatran plus bridging therapy 6.5%; dabigatran without bridging therapy 1.8%).[33]

In the BRIDGE (Bridging anticoagulation in patients who require temporary interruption of warfarin therapy for elective surgery) study, 1,884 patients with atrial fibrillation requiring interruption of warfarin anticoagulation therapy were allocated to either a dalteparin or placebo group. There was no difference between groups in arterial thromboembolic events at 30 days after surgery (0.3 vs. 0.4). However, the incidence of major bleeding was higher in the dalteparin bridging group (3.2% vs. 1.3%, P <0.01), as was minor bleeding (20.9% vs. 12.0%, P <0.01). This study was criticized for the exclusion of high thromboembolic risk patients.[34] The PERIOP-2 study examined whether there is any benefit of bridging therapy after surgery. This study was a randomized clinical trial of 1,471 enrolled patients, 304 of which had a mechanical valve (99 of these had atrial fibrillation simultaneously). There were no significant differences for major thromboembolic episodes between dalteparin and placebo (0.71% vs. 1.11%, respectively). This study showed no benefit of using dalteparin vs. placebo for episodes of major bleeding during the postoperative period (1.46% vs. 2.46%, respectively).

Treatment / Management

How to bridge

Our bridging recommendations follow the AT9 guidelines, which agree with the American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA) 2018 guidelines and are similar to the American College of Surgeons 2018 guidelines.

During the preoperative period:

- Discontinue warfarin 5 days before surgery.

- Three days before surgery, start subcutaneous LMWH or unfractionated heparin (UFH) at therapeutic doses, depending on the patient's renal function.

- Two days before surgery assess INR, if greater than 1.5 vitamin K can be administered at a dose of 1 to 2 mg.

- Discontinue LMWH 24 hours before surgery or 4 to 6 hours before surgery if UFH.

During the postoperative period:

- If the patient is tolerating oral intake, and there are no unexpected surgical issues that would increase bleeding risk, restart warfarin 12 to 24 hours after surgery.

- If the patient received preoperative bridging therapy (high thromboembolic risk) and underwent a minor surgical procedure, resume LMWH or UFH 24 hours after surgery. If the patient underwent a major surgical procedure, resume LMWH or UFH 48 to 72 hours after surgery.

- Always assess the bleeding risk and adequacy of homeostasis before the resumption of LMWH or UFH[4][12][18][35] (A1)

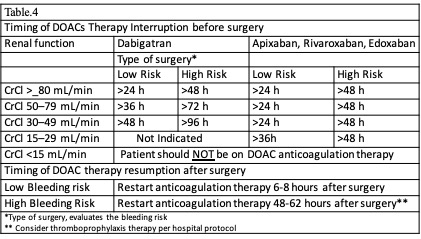

How to Manage Patients on DOAC Anticoagulation Therapy Undergoing Elective Surgery

It is important to note that bridging therapy is not indicated in patients on DOACs. The predictable pharmacological effect of DOACs allows a properly timed interruption of anticoagulation therapy before surgery. Various societies have issued recommendations about the timing of DOAC interruption. Our recommendations are based on the American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus (2017), the European Heart and Rhythm Association (2018), and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA) (2018).[4][19][20] The appropriate timing interruption for patients on DOAC anticoagulation is based on the invasiveness and bleeding risk of the procedure, pharmacokinetic profile of the DOAC, and clinical characteristics of the patient (renal function and liver function). See Table. Timing Interruption of Direct Oral Anticoagulants. As a common recommendation among guidelines, DOACs should be held 3 half-life times before low-risk procedures and 5 half-life times before high-risk procedures. Nevertheless, some procedures are considered less than low bleeding risk, such as a colonoscopy without biopsy, where DOAC therapy may be continued (see Table. Timing Interruption of Direct Oral Anticoagulants). Betrixaban is a new inhibitor of factor Xa. Though many aspects of the clinical use of this drug are still under study, ASRA (2018) recommends betrixaban interruption at least 72 hours before a neuraxial block. ASRA also recommends at least 5 hours between catheter removal and reinitiation of the drug.[36](B3)

In 2019, a new strategy was published in the PAUSE study, a prospective clinical trial evaluating a standardized approach for perioperative management of DOACs. The interruption scheme used in this study was simple. For high-bleeding-risk procedures, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran were suspended 48 hours before surgery in patients with CrCl>50 ml/min. If the renal function was compromised (CrCl< 50 ml/min), these drugs were interrupted for 4 days before surgery. For low-bleeding-risk procedures, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran were interrupted 24 hours before surgery in patients with CrCl>50 ml/min. If the renal function was compromised (CrCl <50 ml/min), drugs were suspended 2 days before the procedure. Regardless of renal function, all drugs were reinitiated at 48 hours for high-bleeding-risk surgical procedures and 24 hours for low-bleeding-risk procedures. The 30-day postoperative rate of major bleeding was 1.35% (95% CI, 0%-2.00%), and the rate of arterial thromboembolism was 0.16% (95% CI, 0%-0.48%). However, more studies are needed in patients with high surgical bleeding risk.[37]

How to Manage Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery

Ideally, patients with recent coronary stent implantation should postpone elective surgery during critical periods post-placement (6 weeks for bare metal stents and 6 months for drug-eluting stents). If elective surgery cannot be postponed, dual antithrombotic therapy should be continued throughout the perioperative period. In patients at high risk of cardiac events, aspirin should be continued throughout the perioperative period, with clopidogrel and prasugrel discontinued 5 days before surgery and resumed 24 hours postoperatively. For patients at low risk of cardiac events, dual antiplatelet therapy can be discontinued 7 to 10 days before surgery and restarted 24 hours postoperatively.[4]

Considerations for Patients Undergoing Neuraxial Anesthesia

The following recommendations for neuraxial puncture and catheter removal are based on the European Society of Anesthesiology and ASRA. These recommendations include the timelines for interrupting and resuming anticoagulation after the puncture, catheter manipulation, or removal. For patients treated with intravenous UFH, the infusion should be interrupted 4-6 hours before puncture or catheter removal/manipulation. However, if the patient receives UFH subcutaneously, the drug should be interrupted 8-12 hours before puncture or catheter removal/manipulation. Independent of the route of UFH administration, the drug can be restarted 1 hour after puncture or catheter removal/manipulation. For patients receiving a prophylactic dose of LMWH, the drug should be interrupted for 12 hours before puncture or catheter removal/manipulation and 24 hours if the dose is therapeutic. Independent of LMWH dose, the drug may be restarted 4 hours after puncture or catheter removal/manipulation. If the patient receives fondaparinux at a prophylactic dose (2.5 mg/day), it should be stopped 36-42 hours before any neuraxial approach and might be resumed 6 to 12 hours post-procedure. For patients receiving DOACs, the interruption time varies according to the specific drug. Patients on rivaroxaban at a prophylactic dose (less than 10 mg/day) should have the drug interrupted 22 to 26 hours before a neuraxial approach. If the patient is on apixaban at a prophylactic dose, it should be discontinued 26 to 30 hours before a neuraxial puncture or catheter placement. Both of these drugs may be restarted 4 to 6 hours after the puncture or catheter removal/manipulation. If the patient is on coumarin anticoagulation, the INR should be less than 1.4 before any neuraxial approach. Drugs such as NSAIDs, including aspirin, do not require interruption for neuraxial anesthetic interventions. However, others, such as cilostazol, require 42 hours of an interruption before neuraxial anesthesia and can be resumed 5 hours after the puncture or catheter removal.[4]

How to Perform Emergency Reversal of Anticoagulation

Definitions of emergency and urgent surgery can vary slightly between guidelines. An urgent procedure is defined as one that can be delayed up to 24 hours, giving time to the physician to conduct anticoagulation reversal based on repeated coagulation tests. On the other hand, the emergent scenario can be defined as one in which the patient requires surgical intervention in less than 1 hour or is experiencing life-threatening bleeding. In emergent cases, the amount of time, the number of coagulation tests that can be performed, and opportunities to delay the procedure until the bleeding risk is lower are limited.[38]

Reversal of warfarin: For non-significant bleeding with alterations of the INR, conservative strategies such as interruption of the drug and oral vitamin K are suitable options. In the emergent scenario, the reversal of warfarin anticoagulation is based on prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) administration as follows:

- INR 2-4: PCC 25 IU/kg IV

- INR ≥4-6: PCC 35 IU/kg IV

- INR >6: PCC 50 IU/kg IV

- Vitamin K: 10 mg IV administered slowly

- FFP: 10 to 20 ml/kg

- Trauma patients: 1 gm of tranexamic acid can be used at arrival, and a repeat dose of 1 gm in 8 hours

- PCC is commercially available as a prothrombin complex concentrate that both contains heparin and is thus contraindicated in patients with a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.[13]

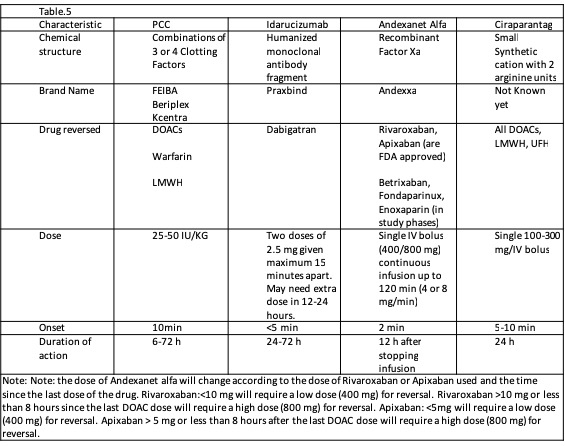

The required time for anticoagulant reversal and INR correction with vitamin K and PCC are 6 to 24 hours and 15 minutes after a 10-minute to 1-hour infusion, respectively. FFP should be administered if ongoing bleeding or PCC is unavailable. The timing of anticoagulation reversal depends on the timing of the complete infusion. Complete reversal usually takes up to 32 hours. PCC must be administered with vitamin K.[39] Reversal of DOACs: The FDA recently approved andexanet alfa for reversing the anticoagulative effects of apixaban and rivaroxaban.[40] The effects of andexanet alfa also seem to be extended to betrixaban and edoxaban; however, more studies are needed. DOAC anticoagulation represents a problem for the clinician. For several years, the first-line option for the reversal of anticoagulation was PCC. However, evidence about prothrombin complex concentrate effectiveness is controversial. With the approval of new specific reversal medications, its future use is uncertain (see Table. Anticoagulation Reversal Agents for Patients on DOACs). What is known is that the cost of the specific new reversal drugs is still high, limiting their use and widespread availability. A complete reversal treatment with andexanet alfa can cost around $50,000, compared to the full treatment with prothrombin complex concentrate, which is about $5,000.[41](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis to consider with perioperative anticoagulants include the following:

- Acute Anemia

- Afibrinogenemia

- Child abuse

- Dysfibrinogenemia

- Epistaxis

- Factor V deficiency

- Factor X deficiency

- GI bleeding

- Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

- Liver failure

- Munchausen syndrome

- Subdural hematoma

- Type A haemophilia

- Type B haemophilia

Complications

There are 2 major complications of poor management of perioperative anticoagulation. The first is bleeding, which occurs if the provider fails to interrupt anticoagulation therapy in an appropriate timeframe. On the other hand, however, patients who have their anticoagulation interrupted too early in the perioperative period are at high risk of thromboembolic events, as surgical procedures themselves induce a hypercoagulable state. Thus, appropriate interruption of anticoagulation in the perioperative period is a delicate balancing act between the potentially severe complications of bleeding and thrombosis, requiring strict attentiveness of the managing provider.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing perioperatively the patient receiving anticoagulation therapy is the responsibility across all disciplines of the healthcare team. First, it is the nurse's responsibility to ensure the information on anticoagulation therapy and diagnoses is correct for the patient upon admission for preoperative testing/physical exam. During the preoperative visit, the surgeon and anesthesiologist are responsible for ensuring this information is correct and deciding how the patient can be managed perioperatively. Once that decision is made, it is the responsibility of the physician to explain this information in detail, the nurse to review this before discharge, and finally, the pharmacist to answer any questions or reiterate this information. On the day of surgery, operative nurses, physicians, and pharmacy personnel have their usual duties of ensuring the patient receives appropriate operative care per protocol for the procedure. Postoperatively, the physician is responsible for placing orders for either continuing to hold or administering the anticoagulation agent, depending on the drug and the patient's scenario. However, the recovery room and hospitalization floor nurses must re-check each prescription before administration according to the patient's diagnoses. Additionally, pharmacy personnel are in charge of reviewing the pharmacological conciliation of the patient.

Finally, it is time for the patient to be discharged. The physician is responsible for writing discharge orders, which may consist of continuing the same anticoagulation regimen prescribed preoperatively, changing the dosage, or even holding medication for some time. Such orders should again be checked by pharmacy personnel. In general, it is the nurse's responsibility to ensure that discharge instructions are received and understood by the patient, thus completing the interdisciplinary care circle for the patient receiving anticoagulation perioperatively. Only by working as an interprofessional team can the morbidity and mortality related to anticoagulation treatments and physician errors be diminished.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Zulkifly H, Lip GYH, Lane DA. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. International journal of clinical practice. 2018 Mar:72(3):e13070. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13070. Epub 2018 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 29493854]

Doherty JU, Gluckman TJ, Hucker WJ, Januzzi JL Jr, Ortel TL, Saxonhouse SJ, Spinler SA. 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Periprocedural Management of Anticoagulation in Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document Task Force. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017 Feb 21:69(7):871-898. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.024. Epub 2017 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 28081965]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKalra K, Franzese CJ, Gesheff MG, Lev EI, Pandya S, Bliden KP, Tantry US, Gurbel PA. Pharmacology of antiplatelet agents. Current atherosclerosis reports. 2013 Dec:15(12):371. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0371-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24142550]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNarouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano D, Buvanendran A, De Andres J, Deer T, Rauck R, Huntoon MA. Interventional Spine and Pain Procedures in Patients on Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications (Second Edition): Guidelines From the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2018 Apr:43(3):225-262. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000700. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29278603]

Hall R, Mazer CD. Antiplatelet drugs: a review of their pharmacology and management in the perioperative period. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2011 Feb:112(2):292-318. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318203f38d. Epub 2011 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 21212258]

Ferri N, Corsini A, Bellosta S. Pharmacology of the new P2Y12 receptor inhibitors: insights on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Drugs. 2013 Oct:73(15):1681-709. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0126-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24114622]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCapodanno D, Milluzzo RP, Angiolillo DJ. Intravenous antiplatelet therapies (glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors and cangrelor) in percutaneous coronary intervention: from pharmacology to indications for clinical use. Therapeutic advances in cardiovascular disease. 2019 Jan-Dec:13():1753944719893274. doi: 10.1177/1753944719893274. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31823688]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDetsi A, Kontogiorgis C, Hadjipavlou-Litina D. Coumarin derivatives: an updated patent review (2015-2016). Expert opinion on therapeutic patents. 2017 Nov:27(11):1201-1226. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2017.1360284. Epub 2017 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 28756713]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnsell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008 Jun:133(6 Suppl):160S-198S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0670. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18574265]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Lecumberri R, Terleira-Fernández AI, Vargas-Castrillón E. Direct-acting oral anticoagulants: pharmacology, indications, management, and future perspectives. European journal of haematology. 2015 Nov:95(5):389-404. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12610. Epub 2015 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 26095540]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlquwaizani M, Buckley L, Adams C, Fanikos J. Anticoagulants: A Review of the Pharmacology, Dosing, and Complications. Current emergency and hospital medicine reports. 2013 Jun:1(2):83-97 [PubMed PMID: 23687625]

Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, Mayr M, Jaffer AK, Eckman MH, Dunn AS, Kunz R. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb:141(2 Suppl):e326S-e350S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2298. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22315266]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMilling TJ Jr, Ziebell CM. A review of oral anticoagulants, old and new, in major bleeding and the need for urgent surgery. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2020 Feb:30(2):86-90. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2019.03.004. Epub 2019 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 30952383]

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Furie KL, Heidenreich PA, Murray KT, Shea JB, Tracy CM, Yancy CW. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019 Jul 9:74(1):104-132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.011. Epub 2019 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 30703431]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMehdi Z, Birns J, Partridge J, Bhalla A, Dhesi J. Perioperative management of adult patients with a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery. Clinical medicine (London, England). 2016 Dec:16(6):535-540 [PubMed PMID: 27927817]

Omran H, Bauersachs R, Rübenacker S, Goss F, Hammerstingl C. The HAS-BLED score predicts bleedings during bridging of chronic oral anticoagulation. Results from the national multicentre BNK Online bRiDging REgistRy (BORDER). Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2012 Jul:108(1):65-73. doi: 10.1160/TH11-12-0827. Epub 2012 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 22534746]

Vivas D, Roldán I, Ferrandis R, Marín F, Roldán V, Tello-Montoliu A, Ruiz-Nodar JM, Gómez-Doblas JJ, Martín A, Llau JV, Ramos-Gallo MJ, Muñoz R, Arcelus JI, Leyva F, Alberca F, Oliva R, Gómez AM, Montero C, Arikan F, Ley L, Santos-Bueso E, Figuero E, Bujaldón A, Urbano J, Otero R, Hermida JF, Egocheaga I, Llisterri JL, Lobos JM, Serrano A, Madridano O, Ferreiro JL, Expert reviewers. Perioperative and Periprocedural Management of Antithrombotic Therapy: Consensus Document of SEC, SEDAR, SEACV, SECTCV, AEC, SECPRE, SEPD, SEGO, SEHH, SETH, SEMERGEN, SEMFYC, SEMG, SEMICYUC, SEMI, SEMES, SEPAR, SENEC, SEO, SEPA, SERVEI, SECOT and AEU. Revista espanola de cardiologia (English ed.). 2018 Jul:71(7):553-564. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2018.01.029. Epub 2018 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 29887180]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHornor MA, Duane TM, Ehlers AP, Jensen EH, Brown PS Jr, Pohl D, da Costa PM, Ko CY, Laronga C. American College of Surgeons' Guidelines for the Perioperative Management of Antithrombotic Medication. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2018 Nov:227(5):521-536.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.08.183. Epub 2018 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 30145286]

Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, Albaladejo P, Antz M, Desteghe L, Haeusler KG, Oldgren J, Reinecke H, Roldan-Schilling V, Rowell N, Sinnaeve P, Collins R, Camm AJ, Heidbüchel H, ESC Scientific Document Group. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. European heart journal. 2018 Apr 21:39(16):1330-1393. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy136. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29562325]

Fabbro M 2nd, Dunn S, Rodriguez-Blanco YF, Jain P. A Narrative Review for Perioperative Physicians of the 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Management of Bleeding in Patients on Oral Anticoagulants. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2019 Feb:33(2):290-301. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.07.023. Epub 2018 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 30146466]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChilders CP, Maggard-Gibbons M, Ulloa JG, MacQueen IT, Miake-Lye IM, Shanman R, Mak S, Beroes JM, Shekelle PG. Perioperative management of antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery following coronary stent placement: a systematic review. Systematic reviews. 2018 Jan 10:7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0635-z. Epub 2018 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 29321066]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceClark NP, Douketis JD, Hasselblad V, Schulman S, Kindzelski AL, Ortel TL, BRIDGE Investigators. Predictors of perioperative major bleeding in patients who interrupt warfarin for an elective surgery or procedure: Analysis of the BRIDGE trial. American heart journal. 2018 Jan:195():108-114. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.09.015. Epub 2017 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 29224638]

Precht C, Demirel Y, Assaf AT, Pinnschmidt HO, Knipfer C, Hanken H, Friedrich RE, Wikner J. Perioperative Management in Patients With Undergoing Direct Oral Anticoagulant Therapy in Oral Surgery - A Multicentric Questionnaire Survey. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2019 May-Jun:33(3):855-862. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11550. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31028208]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChahine J, Khoudary MN, Nasr S. Anticoagulation Use prior to Common Dental Procedures: A Systematic Review. Cardiology research and practice. 2019:2019():9308631. doi: 10.1155/2019/9308631. Epub 2019 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 31275643]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShahi V, Brinjikji W, Murad MH, Asirvatham SJ, Kallmes DF. Safety of Uninterrupted Warfarin Therapy in Patients Undergoing Cardiovascular Endovascular Procedures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiology. 2016 Feb:278(2):383-94. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142531. Epub 2015 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 26203535]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHess CN, Norgren L, Ansel GM, Capell WH, Fletcher JP, Fowkes FGR, Gottsäter A, Hitos K, Jaff MR, Nordanstig J, Hiatt WR. A Structured Review of Antithrombotic Therapy in Peripheral Artery Disease With a Focus on Revascularization: A TASC (InterSociety Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Artery Disease) Initiative. Circulation. 2017 Jun 20:135(25):2534-2555. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.024469. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28630267]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCappato R, Marchlinski FE, Hohnloser SH, Naccarelli GV, Xiang J, Wilber DJ, Ma CS, Hess S, Wells DS, Juang G, Vijgen J, Hügl BJ, Balasubramaniam R, De Chillou C, Davies DW, Fields LE, Natale A, VENTURE-AF Investigators. Uninterrupted rivaroxaban vs. uninterrupted vitamin K antagonists for catheter ablation in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. European heart journal. 2015 Jul 21:36(28):1805-11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv177. Epub 2015 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 25975659]

Calkins H, Willems S, Gerstenfeld EP, Verma A, Schilling R, Hohnloser SH, Okumura K, Serota H, Nordaby M, Guiver K, Biss B, Brouwer MA, Grimaldi M, RE-CIRCUIT Investigators. Uninterrupted Dabigatran versus Warfarin for Ablation in Atrial Fibrillation. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Apr 27:376(17):1627-1636. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701005. Epub 2017 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 28317415]

Birnie DH, Healey JS, Wells GA, Verma A, Tang AS, Krahn AD, Simpson CS, Ayala-Paredes F, Coutu B, Leiria TL, Essebag V, BRUISE CONTROL Investigators. Pacemaker or defibrillator surgery without interruption of anticoagulation. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 May 30:368(22):2084-93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302946. Epub 2013 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 23659733]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBirnie DH, Healey JS, Wells GA, Ayala-Paredes F, Coutu B, Sumner GL, Becker G, Verma A, Philippon F, Kalfon E, Eikelboom J, Sandhu RK, Nery PB, Lellouche N, Connolly SJ, Sapp J, Essebag V. Continued vs. interrupted direct oral anticoagulants at the time of device surgery, in patients with moderate to high risk of arterial thrombo-embolic events (BRUISE CONTROL-2). European heart journal. 2018 Nov 21:39(44):3973-3979. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy413. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30462279]

Tafur A, Douketis J. Perioperative management of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2018 Sep:104(17):1461-1467. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310581. Epub 2017 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 29217632]

Siegal D, Yudin J, Kaatz S, Douketis JD, Lim W, Spyropoulos AC. Periprocedural heparin bridging in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists: systematic review and meta-analysis of bleeding and thromboembolic rates. Circulation. 2012 Sep 25:126(13):1630-9 [PubMed PMID: 22912386]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEssebag V, Proietti R, Birnie DH, Wang J, Douketis J, Coutu B, Parkash R, Lip GYH, Hohnloser SH, Moriarty A, Oldgren J, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz M, Healey JS. Short-term dabigatran interruption before cardiac rhythm device implantation: multi-centre experience from the RE-LY trial. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2017 Oct 1:19(10):1630-1636. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw409. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28339794]

Wight JM, Columb MO. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation-the first randomised controlled trial. Perioperative medicine (London, England). 2016:5():14. doi: 10.1186/s13741-016-0040-5. Epub 2016 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 27280017]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDouketis JD. Perioperative management of patients who are receiving warfarin therapy: an evidence-based and practical approach. Blood. 2011 May 12:117(19):5044-9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-329979. Epub 2011 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 21415266]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSkelley JW, Thomason AR, Nolen JC, Candidate P. Betrixaban (Bevyxxa): A Direct-Acting Oral Anticoagulant Factor Xa Inhibitor. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management. 2018 Feb:43(2):85-120 [PubMed PMID: 29386864]

Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Duncan J, Carrier M, Le Gal G, Tafur AJ, Vanassche T, Verhamme P, Shivakumar S, Gross PL, Lee AYY, Yeo E, Solymoss S, Kassis J, Le Templier G, Kowalski S, Blostein M, Shah V, MacKay E, Wu C, Clark NP, Bates SM, Spencer FA, Arnaoutoglou E, Coppens M, Arnold DM, Caprini JA, Li N, Moffat KA, Syed S, Schulman S. Perioperative Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Receiving a Direct Oral Anticoagulant. JAMA internal medicine. 2019 Nov 1:179(11):1469-1478. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2431. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31380891]

Yee J, Kaide CG. Emergency Reversal of Anticoagulation. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2019 Aug 6:20(5):770-783. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2018.5.38235. Epub 2019 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 31539334]

Sarode R, Milling TJ Jr, Refaai MA, Mangione A, Schneider A, Durn BL, Goldstein JN. Efficacy and safety of a 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate in patients on vitamin K antagonists presenting with major bleeding: a randomized, plasma-controlled, phase IIIb study. Circulation. 2013 Sep 10:128(11):1234-43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002283. Epub 2013 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 23935011]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSiddiqui F, Tafur A, Ramacciotti LS, Jeske W, Hoppensteadt D, Ramacciotti E, Iqbal O, Fareed J. Reversal of Factor Xa Inhibitors by Andexanet Alfa May Increase Thrombogenesis Compared to Pretreatment Values. Clinical and applied thrombosis/hemostasis : official journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 2019 Jan-Dec:25():1076029619863493. doi: 10.1177/1076029619863493. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31298056]

Kustos SA, Fasinu PS. Direct-Acting Oral Anticoagulants and Their Reversal Agents-An Update. Medicines (Basel, Switzerland). 2019 Oct 15:6(4):. doi: 10.3390/medicines6040103. Epub 2019 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 31618893]