Introduction

Erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN) is a condition that was described (rash) as early as the 15th century by a pediatrician named B. Metlinger and has been associated with a reaction to meconium to the baby's skin. The condition's name has changed several times, from erythema populated to erythema dyspepsia and erythema neonatorum allergicum. In 1912, an Austrian pediatrician, Dr Karl Leiner named the condition erythema toxicum neonatorum; currently, this is the denomination used for these skin findings.[1]

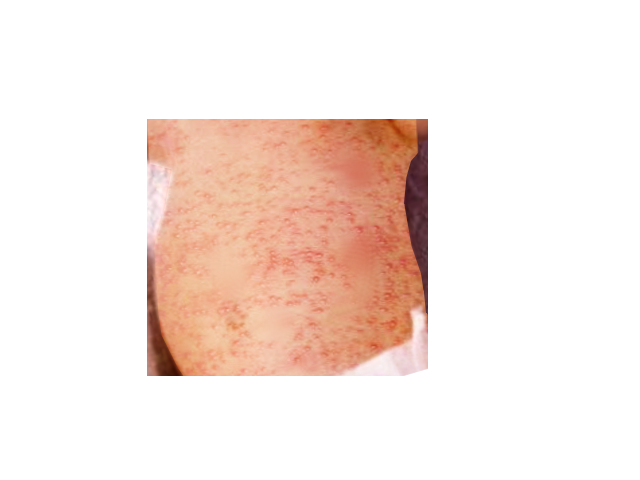

The eruption features small yellowish pustules and papules surrounded by an irregular reddish wheal. Most lesions are temporary, often disappearing within a few hours and reappearing elsewhere (see Image. Erythema Toxicum). Aside from the soles and palms, these lesions can occur on any body part. The skin disorder presents within the first week of life and usually resolves within 7 to 14 days.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Erythema toxicum neonatorum is a benign, self-limited, transient, evanescent eruption in approximately 48% to 72% of full-term infants. Results from a 1986 study reported that 40.8% of 5387 Japanese neonates examined over 10 years were identified as having erythema toxicum neonatorum. Preterm infants with a birth weight of less than 2500 grams are less likely to be affected.[2][3] There are a significant amount of eosinophils in the lesions, which some suspect may be due to an allergic response.

Epidemiology

While there is no racial predilection, males appear more commonly affected compared to females. In 356 Spanish newborns, 25.3% had erythema toxicum neonatorum (61.9% were males, and 38.1% were females). Recurrence is exceedingly rare, although some reports of recrudescence have occurred within the first month of life.[4]

Pathophysiology

The etiology of this condition is entirely unknown: a graft-versus-host reaction against maternal lymphocytes has been postulated as a possible mechanism, but recent study results failed to show the presence of maternal cells in these lesions. Another theory proposes an immune response to microbial colonization through the hair follicles as early as one day of age. Immunohistochemical study of lesions from 1-day-old infants supports the accumulation and activation of immune cells in erythema toxicum neonatorum lesions.

A variety of inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL)-1alpha; IL-1beta; IL-8; eotaxin, aquaporins 1 and 3; psoriasin; nitric oxide synthetases 1, 2, and 3; and HMGB-1 have been associated with erythema toxicum neonatorum immunohistochemically. Tryptase-expressing mast cells, however, not the cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide LL-37, have been located in erythema toxicum neonatorum biopsy specimens.

Histopathology

The pustules form below the stratum corneum or deeper in the epidermis and represent collections of eosinophils that accumulate around the upper portion of the pilosebaceous follicle. The eosinophils can be demonstrated in Wright-stained smears of the intralesional contents. The pustules usually contain around 50% eosinophils and can approach up to 95%.

Cultures are sterile; no organisms are seen on Gram stain. Microscopic observation of the erythematous macules and patches shows superficial dermal edema with a mild diffuse and perivascular eosinophilic infiltrate. Papules display mild hyperkeratosis and a more pronounced edema with eosinophilic infiltration. Hair follicles, eccrine glands, and ducts tend to be strongly affected.

History and Physical

The lesions are firm, yellow-white, 1 to 3-mm papules or pustules with a surrounding irregular erythematous base. They are also described as having a “flea-bitten appearance” or a papule surrounded by a sea of erythema. At times, splotchy erythema is the only manifestation. Lesions may be sparse or numerous, clustered in several sites, or widely dispersed over much of the body surface.

Erythema toxicum neonatorum has been described as having 2 likely variations: an erythematous papular or a pustular variant. Macules appear within and outside the erythematous lesions during the first presentation day. The macules usually begin on the cheeks and rapidly spread to the forehead and the rest of the face, chest, trunk, and extremities.

Still, several case reports of patients with erythema toxicum neonatorum lesions over the skin of the scrotum exist. The blotchy appearance ensues as the macules become confluent, sometimes resembling urticarial lesions on the trunk. The palms and soles are usually spared; this pattern of involvement may be correlated to the distribution of hair follicles.

Clinicians sometimes find it challenging to identify erythema toxicum neonatorum in babies with darker skin. Erythematous macules are often evanescent, but papules tend to appear when they persist, and papules may also arise as de novo. Some papules may become superficial, particularly on the skin of the back and abdomen.

Pustules becoming secondarily infected is uncommon. The peak incidence occurs on the second day of life, but new lesions may erupt during the first few days as the rash waxes and wanes, although recurrences may occur in up to 11% of neonates. The onset may occasionally be delayed in premature infants for several days to weeks. No systemic manifestation is associated with the condition, and one might rarely see some eosinophilia in blood study results—and counts as high as 18% have been reported.[5][6]

Evaluation

No laboratory workup is usually required as the diagnosis is usually clinical. The sterile papule may reveal eosinophils. In some infants, herpes simplex and varicella-zoster should be ruled out; fungal infection should be ruled out with a simple potassium hydroxide preparation.[7][8][9]

Treatment / Management

Treatment starts with educating the parents about the natural course of the condition, which is benign and will resolve without any sequelae. Because the appearance of the rash creates significant parent or caregiver concerns, reassuring them is paramount. Tell them to gently cleanse the area with gentle products designed for sensitive skin.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses of this condition include sepsis, staphylococcal folliculitis,[10] acne neonatorum, pyoderma, congenital candidiasis, herpes simplex, infantile acropustulosis, neonatal varicella, pustular miliaria, miliaria cristallina, miliaria rubra, transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM), and incontinentia pigmenti.[11][12][13]

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis and incontinentia pigmenti can be distinguished easily from erythema toxicum neonatorum. Both conditions are present at birth, but TNPM involves the palms and soles, where there is no erythematous component, and it only shows neutrophils with cytologic debris.[14] Also, both conditions can present at the same time.[15]

Incontinentia pigmenti presents with vesicles filled with eosinophils, and is more common in boys but is rarely pustular, and the appearance is in a linear pattern different from the pattern of erythema toxicum neonatorum. The distribution of the rash can also be useful in differentiating erythema toxicum neonatorum from infantile acropustulosis. In contrast, erythema toxicum neonatorum spares the palm and soles; the hallmark of infantile acropustulosis characteristically includes the acral surfaces, hence its name.

Erythema toxicum neonatorum can be differentiated from miliaria rubra, a condition in which the vesicles are related to the sweat ducts rather than hair follicles, and the lesions contain mononuclear cells rather than eosinophils. Congenital cutaneous candidiasis can also present at birth or in the first days of life, with a diffuse erythematous rash with overlying papules, pustules, and vesicles. Still, the palms and soles are not spared.

Prognosis

The prognosis is excellent with lesions resolving within 7 to 14 days. There are no residual sequelae.

Complications

ETN is a benign and self-limiting neonatal skin condition, and complications are pretty rare. However, its transient pustular lesions can occasionally lead to secondary bacterial infections if disrupted or scratched—although uncommon. The primary challenge with ETN lies in its potential for misdiagnosis, as it may mimic severe conditions such as neonatal sepsis, viral exanthems, or pustular dermatoses, leading to unnecessary investigations or treatment delays for actual pathology.

Additionally, the distinctive appearance of ETN can cause significant parental and caregiver anxiety, necessitating clear communication and reassurance about its harmless nature. In rare cases, persistent or atypical ETN-like eruptions may prompt further evaluation to exclude underlying immunological or dermatological disorders. While ETN has no inherent long-term sequelae, careful differentiation from more serious conditions is essential.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Long-term follow-up is required as there is a link between erythema toxicum and eosinophilic esophagitis. Children who present with symptoms of esophagitis should be asked about a rash in the neonatal period.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Effective patient education is essential to alleviating parents' and caregivers' concerns and ensuring appropriate care. Healthcare professionals should emphasize that ETN is a common neonatal skin condition with no long-term consequences caused by transient immune activation rather than infection or external factors. Parents and caregivers should be reassured that the condition resolves spontaneously within a few days to weeks without intervention.

To prevent unnecessary interventions, parents and caregivers should be educated about the characteristic appearance of ETN lesions—erythematous macules, papules, and pustules—and advised to avoid overhandling or applying topical treatments that could irritate the skin. Clinicians should encourage routine neonatal skincare practices, such as gentle cleansing and avoiding excessive exposure to harsh soaps or chemicals, while emphasizing that ETN is not caused by poor hygiene or allergies. Last, parents and caregivers should be instructed to seek medical attention if lesions appear atypical, persist longer than expected, or are associated with systemic symptoms to rule out other conditions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Erythema toxicum is a benign self-limited skin disorder that is only seen in neonates. Unfortunately, many worried parents and caregivers bring their children to the clinician for medical care and then undergo unnecessary testing and treatment. A dermatology referral is recommended when the primary care clinician is unsure about the diagnosis.

The key to this condition is parent and caregiver education. The primary care clinician, pharmacist, and healthcare professionals in the emergency department must reassure the parent or caregiver that the condition is harmless and will resolve spontaneously. Parents and caregivers should be told to avoid unnecessary treatments, which may lead to more harm than good. The prognosis for most neonates is excellent, with the rash resolving in 10 to 14 days.[16]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Reginatto FP, Muller FM, Peruzzo J, Cestari TF. Epidemiology and Predisposing Factors for Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum and Transient Neonatal Pustular: A Multicenter Study. Pediatric dermatology. 2017 Jul:34(4):422-426. doi: 10.1111/pde.13179. Epub 2017 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 28543629]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReddy HB, Gandra NR, Katta TP. Cutaneous Changes in Neonates in the First 72 Hours of Birth: An Observational Study. Current pediatric reviews. 2017:13(2):136-143. doi: 10.2174/1573396313666170216120230. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28215177]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRayala BZ, Morrell DS. Common Skin Conditions in Children: Neonatal Skin Lesions. FP essentials. 2017 Feb:453():11-17 [PubMed PMID: 28196316]

Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian journal of dermatology. 2015 Mar-Apr:60(2):211. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152558. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25814724]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReginatto FP, DeVilla D, Muller FM, Peruzzo J, Peres LP, Steglich RB, Cestari TF. Prevalence and characterization of neonatal skin disorders in the first 72h of life. Jornal de pediatria. 2017 May-Jun:93(3):238-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2016.06.010. Epub 2016 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 27875703]

Reginatto FP, Villa DD, Cestari TF. Benign skin disease with pustules in the newborn. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2016 Apr:91(2):124-34. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164285. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27192509]

Aktaş H, Alp Erdal S. Oral mucosal and skin lesions observed in the first 48 hr in newborns. Journal of cosmetic dermatology. 2021 Nov:20(11):3649-3655. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14013. Epub 2021 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 33609325]

Firouzi H, Jalalimehr I, Ostadi Z, Rahimi S. Cutaneous Lesions in Iranian Neonates and Their Relationships with Maternal-Neonatal Factors: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. Dermatology research and practice. 2020:2020():8410165. doi: 10.1155/2020/8410165. Epub 2020 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 32425998]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoyal T, Varshney A, Bakshi SK. Incidence of Vesicobullous and Erosive Disorders of Neonates: Where and How Much to Worry? Indian journal of pediatrics. 2021 Jun:88(6):574-578. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0592-9. Epub 2011 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 22037857]

Yoshida S, Yatsuzuka K, Chigyo K, Kuroo Y, Takemoto K, Sayama K. A Case of Eosinophilic Pustular Folliculitis since Birth. Children (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Jan 7:8(1):. doi: 10.3390/children8010030. Epub 2021 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 33430336]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceQuazi S, Choudhary S, Singh A, Madke B, Khan K, Singh S. A cross-sectional study on the prevalence and determinants of various neonatal dermatoses. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2023 Nov:12(11):2942-2949. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_513_23. Epub 2023 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 38186839]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDe María MK, Borda KM, Arretche VN, Gugelmeier N, Mombelli R, de Los Santos AV, Acosta MA, Álvarez M, Pose GL, Borbonet D, Martínez MA. Neonatal Dermatologic Findings in Uruguay: Epidemiology and Predisposing Factors. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2021 May:112(5):414-424. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2020.11.019. Epub 2020 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 33321117]

Sanaphay V, Sengchanh S, Phengsavanh A, Sanaphay A, Techasatian L. Neonatal Birthmarks at the 4 Central Hospitals in Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. Global pediatric health. 2021:8():2333794X21990908. doi: 10.1177/2333794X21990908. Epub 2021 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 33614846]

Vendhan S, Vasudevan B, Neema S. Transient Neonatal Pustulosis - A Precocious form of Erythema Toxicum Neonatarum. Indian dermatology online journal. 2023 Jul-Aug:14(4):572-573. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_566_22. Epub 2023 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 37521223]

Snyder KAM, Voelckers AD. Newborn Skin: Part I. Common Rashes and Skin Changes. American family physician. 2024 Mar:109(3):212-216 [PubMed PMID: 38574210]

Kanada KN, Merin MR, Munden A, Friedlander SF. A prospective study of cutaneous findings in newborns in the United States: correlation with race, ethnicity, and gestational status using updated classification and nomenclature. The Journal of pediatrics. 2012 Aug:161(2):240-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.02.052. Epub 2012 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 22497908]