Mohs Micrographic Surgery of Uncommon Tumors (Angiosarcoma, Eccrine, Paget, and Merkel Cell)

Mohs Micrographic Surgery of Uncommon Tumors (Angiosarcoma, Eccrine, Paget, and Merkel Cell)

Introduction

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a surgical technique commonly used to treat cutaneous malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC). MMS is performed in several stages, progressively removing malignant tissue while preserving healthy tissue and achieving high cure rates.[1] The main advantage of MMS is the ability to assess all margins through the removal of tumor layers, which are processed in frozen sections. This histological assessment of the entire margin is crucial to determine tumor clearance before defect reconstruction, usually occurring in a single surgical session.[1][2]

MMS is currently the mainstay treatment for non-melanoma skin cancer, including SCC and BCC.[3] MMS has shown benefits in treating these cancers, significantly reducing recurrence rates in both tumors.[3][4] Uncommon cutaneous malignancies (UCMs) are skin tumors that, although infrequent, are usually associated with poor outcomes and worse prognosis compared to their more common counterparts. MMS has proven useful in treating UCMs, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.[4] Recently, several studies have highlighted different UCMs treated with MMS, including angiosarcoma, eccrine malignant tumors, Paget disease, and Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

Due to their high metastatic potential, MMS's role in treating UCMs has been questioned, especially in angiosarcoma and MCC.[5] Usually, UCMs benefit from treatment with wide local excisions (WLEs). However, MMS has been used alternative option for UCMs over the past decade, supported by several case reports and series demonstrating its beneficial effects on UCM management.[4][6] In recent years, study groups worldwide have assessed the efficacy, impact on prognosis, and relevance of MMS beyond its common indications.[4] Nonetheless, the value of MMS for some UCMs remains to be fully defined.[1][7] The following discussion reviews the available evidence on the role of MMS in treating specific UCMs.

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

The literature reports several case series on MMS as a treatment option for angiosarcoma, eccrine malignant tumors, Paget disease, and MCC. Recently, some study groups have contributed larger registries that broaden the understanding of MMS's advantages and possible disadvantages in treating these tumors.

Angiosarcoma

Cutaneous angiosarcoma (cAS) is an uncommon malignant tumor derived from endothelial cells. In its cutaneous form, it is often associated with radiation therapy and lymphedema. This tumor accounts for only 1% of all sarcomas.[8] Gender preference does not exist, and it usually occurs in adults aged 50 or older, with the average age of presentation being 75.[8][9]

Clinically, the tumor has unremarkable features and can be seen as a plaque, several nodules, papules, or a tumor with a red to violaceous color (see Image. Cutaneous Angiosarcoma). cAS has poor survival rates at 5 years, mainly due to early regional nodal metastases and multiorgan involvement at the time of the diagnosis.[1][8] Sporadic cases of cAS typically occur on the scalp, appearing as subtle violaceous papules and nodules that slowly merge or grow to form tumors. These generic characteristics can lead to a late diagnosis.

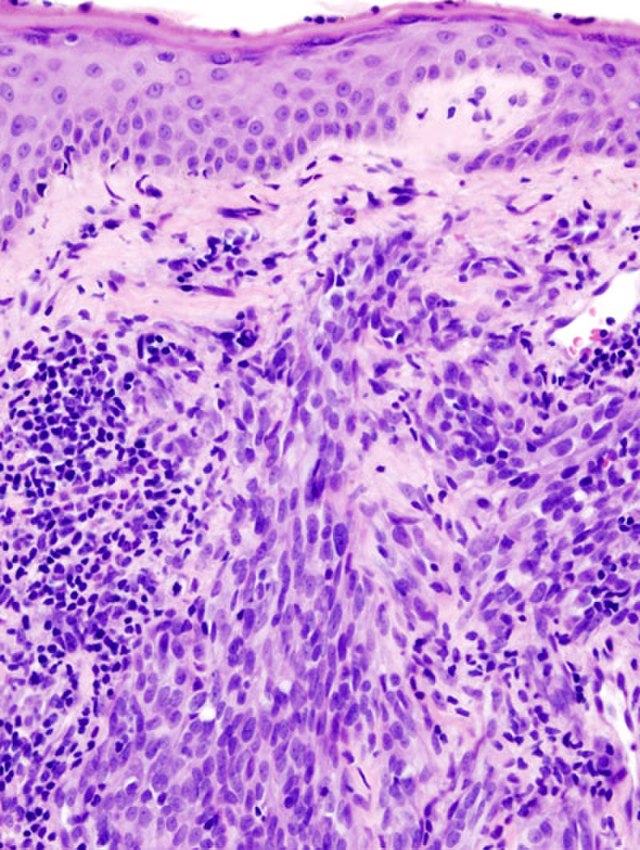

Histological diagnosis of cAS can be challenging due to the cellular component's morphological variability and lack of differentiation. Typically, cAS appears as a dermal tumor with irregular anastomosing vessels, pleomorphic epithelial cells, and numerous mitoses. Highly undifferentiated variants may present as dermal tumor sheets of pleomorphic cells without clear vascular structures within the tumor. Immunohistochemical (IHC) stains such as CD34 and CD31 are essential in cases where vascular structures are inconspicuous (see Image. Histology of Cutaneous Angiosarcoma).[10]

Holden et al acknowledge that tumor size is the most important factor influencing survival rates. Tumors smaller than 10 cm have better prognosis and survival rates.[11] Additionally, tumor location affects 5-year survival rates, with lower rates for tumors located on the head and neck (11%-53%) compared to tumors located elsewhere (26%-51%).[8]

MMS has been used as a therapeutic option for cAS for several years. In 1977, Mikhail and Kelly reported a case of cAS treated with WLE, with the histological study conducted using the paraffin-embedded MMS technique, showing no recurrences after 4 years of close follow-up.[12] In 1993, Goldberg and Kim performed the first reported case of conventional fresh technique MMS in a cAS, with no local recurrences after 18 months.[9] Later that year, Muscarella reported a case of cAS located in the temple treated with MMS, also showing no recurrences after 20 months.[13]

More recently, Wollina et al in 2013, reported a case series of various mesenchymal tumors and their experience in the surgical treatment of these tumors over the past 10 years. The series included 7 cases of cAS, 1 of which had lymph node involvement. Of the remaining cases, 5 were treated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and wide excision. The only case located on the face was treated with MMS and received adjuvant radiotherapy, with no local recurrences after 72 months.[14] In 2020, the Spanish registry of Mohs surgery (REGESMOHS) included 73 uncommon cutaneous tumors from 2013 to 2018; 2 were cAS, and only 1 was treated with MMS. No recurrence was reported in the case treated with MMS.[14][7]

Eccrine Malignant Tumors

Eccrine porocarcinoma/eccrine carcinoma: Porocarcinoma or eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) is an uncommon cutaneous adnexal tumor of the sweat glands' acrosyringium. This tumor is usually located on the head, neck, and extremities of older patients, predominantly in men aged 65 or older. However, some reports suggest that EPC may be more frequent in women.[4][15][16] The preferred location of EPC is the lower extremities, followed by the head and neck.[16] Chronic immunosuppression is considered a risk factor for developing de novo EPC and has been linked to the malignant transformation of eccrine poromas, their benign counterparts, into EPCs.[17][18] Clinically, EPC presents as a flesh-colored nonspecific papule or nodule, ranging from 1 to 10 cm (see Image. Eccrine Porocarcinoma).[19] Bleeding, rapid growth, and tenderness can be signs of malignant transformation. This process of malignization from a poroma to an EPC can take up to 20 years.[16][17]

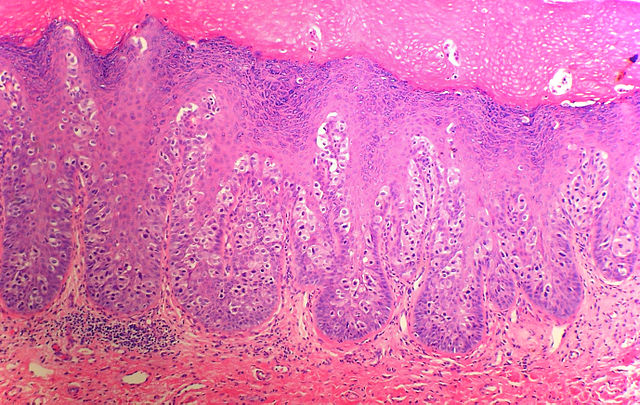

Histologically, EPCs are basaloid tumors attached to the epidermis, formed by cohesive small cells, sometimes called poromatous cells of epithelial origin. Ductal differentiation and cellular pleomorphism are usually observed (see Image. Histology of Eccrine Porocarcinoma).[16] The standard treatment for EPC is WLE. After treatment, the average recurrence rate of this tumor is 20%, often occurring as late as 12 years after treatment.[15][20] Nodal metastases occur in approximately 10% to 20% of the cases and can correlate with mortality rates as high as 60%.[18][21][22]

In 1999, Wittenberg et al reported 5 cases of EPC treated with MMS, and tumor sizes in these cases ranged from 1 to 2.5 cm. After a follow-up time of 5 to 42 months, no recurrences were reported.[15] In 2015, Xu et al reported 27 cases treated with MMS, with no local recurrences after more than 6 years of follow-up. However, 2 patients from this case series developed nodal metastases after MMS, resulting in a 93% success rate for monotherapy with MMS and a 7% incidence of nodal metastases.[17] The same year, Tidwell et al reported 5 cases of EPC treated with MMS with no recurrences after an 11-month follow-up.[23]

Song et al reported 21 cases of EPC treated with MMS with only 1 nodal recurrence.[24] According to a meta-analysis by Le et al, MMS improved outcomes by significantly reducing recurrences of head and neck EPCs treated with this technique.[25] In the 19-year experience of Tolkachjov et al at the Mayo Clinic, 9 patients were diagnosed with EPC and treated with MMS. Over a mean follow-up period of 39 months, no reports of recurrences or metastatic disease were reported.[16]

Hidradenocarcinoma: Likewise, hidradenocarcinoma is also considered an eccrine malignant tumor. Hidradenocarcinoma is extremely rare and difficult to differentiate from its benign counterpart, hidradenoma.[26] Distinctive features that can accurately indicate a hidradenocarcinoma diagnosis are not yet available. Clinically, hidradenocarcinoma can mimic benign adnexal tumors.

Histologically, hidradenocarcinoma is characterized as a dermal basaloid tumor, similar to hidradenoma, with subtle features that may indicate malignancy, such as scattered nuclear atypia and focal areas of mitoses. Architecturally, hidradenocarcinoma may appear uncircumscribed, with irregularly shaped islands and cords extending into the deep dermis.[26] Clinically, hidradenocarcinoma appears as a single red-violaceous shiny nodule or tumor. The lesion can become locally invasive over time; however, nodal and systemic metastases may occur early in the disease course, with recurrence and metastasis rates reaching 50% and 60%, respectively.[27]

Wildemore et al reported a case series of 3 hidradenocarcinomas—the first case involved a male patient aged 12 who was initially treated with WLE, resulting in positive margins, followed by re-excision using MMS, with no recurrences after 44 months of follow-up. In the second and third cases, a male patient aged 60 and a female patient aged 74 were diagnosed with hidradenocarcinoma and treated with MMS. They showed no recurrences after 30 and 41 months of follow-up, respectively. In these cases, a 4- to 5-mm margin was utilized during MMS to ensure clear margins.[21]

Tolkachjov et al also reported their 10-year experience (1993-2023) treating hidradenocarcinoma with MMS at the Mayo Clinic. A total of 10 patients were treated, and after an average follow-up of 84 months, no recurrences, metastases, or mortality associated with the diagnosis were reported.[28]

Paget Disease

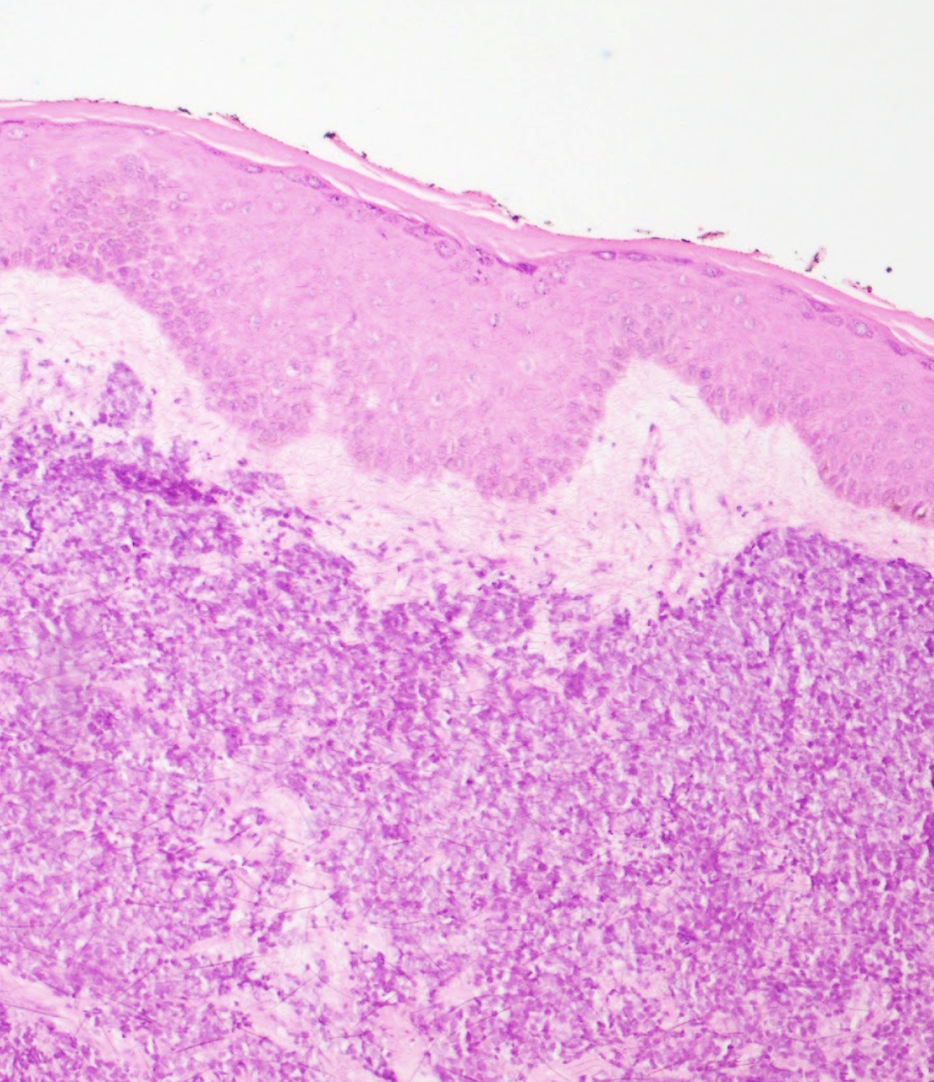

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon neoplastic condition derived from apocrine glands. The usual locations of EMPD are anogenital and axillary areas in women aged 50 and older.[29] Usually, this tumor often exhibits clinically undefined borders and may involve subclinical spread. EMPD presents as an eczematous plaque or patch, typically erythematous or brown, with indurated borders, sometimes eroded, or appearing sclerotic (see Image. Extramammary Paget Disease in the Groin Area).[30] Pruritus is the cardinal symptom associated with EMPD.[31] This neoplastic disease primarily affects the epidermal layer but frequently extends subclinically, with invasive disease reported in up to 21% of cases.

Histologically, EMPD presents as a neoplastic proliferation of atypical vacuolated cells that predominantly infiltrate the basal layer of the epidermis, hair follicles, and sweat glands. Dermal invasion is uncommon. Several histochemical and IHC stains may be positive in this tumor, such as mucin, cytokeratin 20 (CK20), EMA, and CAM 5.2. Nevertheless, the mainstay immunostain for diagnosing Paget disease is cytokeratin 7 (CK7) (see Image. Histology of Extramammary Paget Disease).[30][31]

More than half of the patients (545 in total) with EMPD had an internal neoplasia at the time of diagnosis, including neoplasms of the breast, cervix, ovaries, gallbladder, and liver. Screening is recommended based on the patient's gender, age, and any associated signs and symptoms present.[32] EMPD is usually treated with WLE, and in some cases, when surgery is not an option, topical treatments such as imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil are preferred.[32] Traditional WLE section borders are compromised in up to 97% of the cases. High local recurrence rates have been reported in up to 58% of the patients.[29][32] Subclinical and invasive disease has been reported in up to 21% of EMPD cases.[30][31]

O'Connor et al from the Mayo Clinic reported in 2003 that 1 of the most extensive retrospective reviews of EMPD was treated with WLE and MMS. In this review, a total of 95 patients diagnosed with EMPD underwent treatment—83 cases were treated with WLE, and the remaining 12 with MMS. A favorable recurrence rate for MMS was reported, with only 8% of cases having local recurrences after a 24-month follow-up. In the WLE group, 18 out of the 83 cases recurred (22%) after a 65-month follow-up.[33]

In 2004, Hendi et al reported a retrospective review finding that the recurrence rate for primary EMPD treated with MMS was 16%, compared to 50% for recurrent cases of EMPD treated with MMS. This study also found that the average margin size for MMS in EMPD is 2.5 cm, compared to WLE, where 5 cm margins are usually recommended.[34]

In 2009, Lee et al performed a retrospective review of cases treated with WLE versus cases treated with MMS.[29] In total, 35 patients were included—30 men and 5 women. Of those, 22 patients were treated with WLE, 2 with topical methods, and 11 with MMS. Among the 11 patients treated with MMS, 3 were recurrent cases previously treated with topical alternatives and WLE. A significant difference in recurrence rates between WLE and MMS was found. Recurrence rates for MMS and WLE were 10% (47-month follow-up) and 30% (70-month follow-up), respectively. This study also reported that the mean 5-year survival rates were higher in cases treated with MMS (81.8%) than those treated with WLE (63.6%).[29]

In 2023, Bruce et al performed a prospective observational trial between 2018 and 2022. Patients with EMPD were enrolled and treated either with WLE or MMS-guided WLE. In total, 24 patients received treatment with MMS-guided WLE, with a mean survival rate after 3 years of 93%, compared to the traditional WLE, with a mean survival rate of 65.9%.[31]

In 2023, Yuan et al published a network meta-analysis where different treatments for perineal EMPD were assessed. The analysis included 29 studies and 11 treatment modalities. MMS significantly reduced recurrence rates (OR: 0.18 [0.03–0.87]) in EMPD. In contrast, none of the other treatments (WLE, radiotherapy, and topical) showed statistically significant results.[35]

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

MCC is an uncommon cutaneous malignant tumor of neuroendocrine origin, accounting for less than 0.5% of cutaneous malignancies.[36][37] MCC usually appears in sun-exposed areas, mainly on the face of older, immunocompromised men. Another significant risk factor for developing MCC is polyomavirus infection.[37] Clinically, MCC presents as a painless, rapidly growing, red tumor (see Image. Merkel Cell Carcinoma).

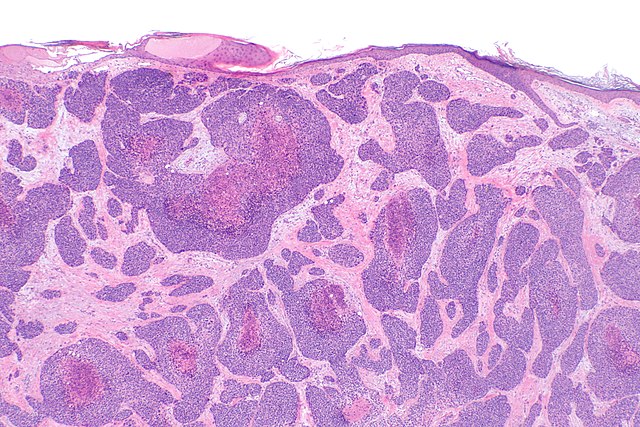

Histologically, MCC is a predominantly dermal tumor with minimal involvement of the papillary dermis, and it consists of diffusely infiltrating small blue round cells with scant cytoplasm and numerous mitoses. IHC aids histological confirmation, with the primary immunostain being CK20 (see Image. Histology of Merkel Cell Carcinoma).[38][39] Heath et al proposed the AEIOU acronym to describe the features of the tumor (A=age, E=expanding rapidly, I=immunocompromised, O=older than 50, and U=UV exposure).[38]

The survival rate of MCC depends on the clinical stage, ranging from 81% for stage I to 11% for stage IV.[39] While WLE is the standard treatment, MMS has been utilized primarily for patients needing tissue preservation (such as tumors on the face, neck, or genital area) or those in the early stages (stage I/II) of the disease. The standardization of margin sizes has been debated, as several cases with positive margins have been reported even when using margins wider than 2 cm. However, a common consensus suggests that tumors less than 2 cm require margins of 1 cm, and tumors greater than 2 cm require margins of 2 cm.[39]

Shaikh et al reported a retrospective cohort study of 2670 cases of MCC treated with MMS and WLE from 2004 to 2009. Of these, 2039 cases were treated with WLE, and 174 were treated with MMS. They found no statistically significant differences in survival rates among the groups.[40] Terushkin et al reported 56 cases of early stages (stage I/II) MCC. Among the 53 cases treated with MMS from 2001 to 2019, no recurrences were reported after a 54-month follow-up.[39][41]

In 2022, Tran et al conducted a retrospective cohort study involving 711 patients with early-stage MCC (no lymph node involvement or metastatic disease). Among them, 60 patients underwent MMS, while 651 were treated with WLE. This study concluded that patients treated with MMS were less likely to require sentinel lymph node biopsy.[36]

A recent study by Su et al included 1185 patients with stage I/II MCC, among whom 90 were treated with MMS and 1095 with WLE. The overall 5-year survival rates were 59.7% for WLE and 65.1% for MMS, with no significant differences between the 2 groups.[42] Similarly, Pearlman et al conducted a retrospective study involving 2806 cases of stage I/II MCC. Of these, 2527 underwent WLE, and 279 were treated with MMS. After a 36-month follow-up, no differences in overall survival were observed between the groups.[43]

Issues of Concern

Overall, most of the tumors mentioned in this activity have poor outcomes, mainly due to late diagnosis. For cAS, to date, there is a consensus that surgery alone is the first-line treatment for cAS.[8] However, MMS has not been as widely used for cAS, given its histological characteristics as a predominantly dermal, ill-defined, and infiltrative tumor often described as discontinuous.[44] Due to these histological features, MMS treatment for cAS may necessitate multiple stages. Imaging is crucial in surgical planning, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans recommended before surgery. Despite wide local excision (WLE), the tumor's multifocality and tissue infiltration often lead to positive margins and a heightened risk of recurrence.[45]

On the contrary, regarding EPC, Belin et al performed an observational study that included 24 cases of histologically confirmed EPC. These cases were heterogeneous and represented different histological variants of EPC, including infiltrative, pushing, and pagetoid subtypes. Regardless of the histological subtype, they observed no significant difference in recurrence rates when comparing margins of more than or equal to 2 cm versus less than 2 cm.[18] Additionally, their study suggested that a modified MMS technique known as "slow Mohs" or paraffin-embedded Mohs might offer advantages for treating infiltrative variants of EPC.

In regards to EMPD, Bruce et al noted that when MMS is utilized for treating EMPD cases, surgical defects may be larger and require significantly more reconstructive time. The authors suggest that this could contribute to why a more aggressive surgical approach, such as WLE, might be considered preferable.[31]

When it comes to MCC treatment, Carrasquillo et al published a systematic review assessing different treatment methods for MCC, with an emphasis on WLE and MMS. They found that the existing literature includes confusing factors, such as tumor size, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and adjuvant therapies, which may impact recurrence and survival rates and are not considered in every study. These complexities underscore the challenge of determining the optimal treatment approach for this specific tumor.[46]

Clinical Significance

UCMs mentioned in this activity (cAS, EPC, Paget disease, and MCC) are rare cutaneous tumors commonly diagnosed in advanced stages. This can occur due to the lack of clinical characteristics suggesting the exact diagnosis, especially for EPC and cAS, but also the aggressive behavior and rapid growth that leads to early metastatic disease, which happens particularly often in cases of MCC. The shortage of surgeons trained to perform MMS worldwide is a known issue. Notably, it is estimated that in 2020, there were 2411 Mohs surgeons in the United States, with significant recent growth in this area’s workforce.[47] However, 94% of these Mohs surgeons practice in metropolitan areas, leaving rural areas underserved.[48] Data on the statistics of Mohs surgeons outside the United States are unavailable in the current literature; however, an equivalent or even higher shortage may be estimated worldwide.

Paraffin-embedded or slow MMS is an excellent option in cases requiring strict tissue sparing due to its location and possible consequences over functionality. Also, this technique might be an option in UCMs where MMS has shown superiority over WLE, such as EPC. This modified MMS technique enables the possibility of generating strong partnership opportunities between pathologists and dermatologists with surgical experience. In EPC and MCC, where MMS has shown significantly better outcomes compared to WLE, it is frequent that the procedure is not regularly performed due to difficulties accessing trained surgeons. Treatment delays must be avoided at all costs, considering the strong impact on overall survival. This is why training pathways for Mohs surgeons must be expanded worldwide to ensure adequate, evidence-based, timely interventions. Substantial evidence is lacking to suggest that MMS improves survival rates for cAS compared to WLE. Potential candidates that benefit from MMS to ensure clear margins while sparing tissue are areas of concern (face and scalp) and small tumors (<5 cm).[49] There are not enough cases in the literature to establish specific indications and benefits in prognosis for the cases that may be good candidates for MMS diagnosed with cAS.[25]

Unlike cAS, MMS in EPC and hidradenocarcinoma treatment has consistently proven to be an effective alternative, with evidence suggesting better survival rates for MMS compared to WLE. As of today, a consensus on the treatment of EPCs does not exist. Patients undergoing WLE with 2- to 3-cm margins have a survival rate of 80%. WLE continues to be the standard treatment.[16][18] MMS has been deemed as an appropriate treatment for EPC by several studies.[22][23] Cases of ECP treated with MMS resulted in lower lymph node metastatic rates compared to WLE (4.2% versus 20%).[22][25] However, Vleugels et al reported a case of an EPC treated with MMS with no history of clinical nodal disease or lymphovascular involvement in the biopsy. After 2 years of regular follow-up, the patient presented to the clinic with lymph node metastases. Therefore, strict clinical and imaging follow-up after treatment, even when clear margins are achieved, should be considered, given the possibility of occult metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.[18]

A standardized imaging technique for assessing EPC does not exist; however, performing images in these cases is highly recommended, considering the high risk of metastatic disease. Song et al found that even when tumor size itself has no significance over prognosis in EPC, factors such as ulceration, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, multicentricity, and progressive growth can correlate with a higher metastatic rate.[24] Nevertheless, as suggested by Tolkachjov et al, sentinel lymph node biopsy should be considered in tumors with high mitotic rates (>14 mitoses per high power field) and a depth of more than 7 mm.[16] For EPC treated with MMS, similar to hidradenocarcinoma, a 3- to 5-mm margin has been advocated depending on the histological subtype, with 5 mm for pagetoid, slow, or paraffin-embedded Mohs for infiltrative variants.[22] For recurrent cases, WLE is the treatment of choice for hidradenocarcinoma.[21]

In EMPD, 1 of the downsides of performing MMS after topical treatments such as 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod is that the remaining tumor can sometimes be clinically concealed. These areas, where the tumor is still subclinically present, may not be visually apparent to the eye and can be located far away from the clinically apparent tumor, leading to inaccurate margin delimitation.[29] Chang et al implemented a modified spaghetti technique of MMS, which includes assessing the internal (mucosal) border of the neoplastic condition in addition to evaluating the external cutaneous border (tumor margin) before excision.[32] EMPD has been documented to extend up to 5 cm away from the clinical borders in some cases. However, this is not true in every case; this variability should be considered when surgical planning is being performed, especially for tumors located in the genital area.[34]

O’Connor et al suggest that modified MMS with the classic spaghetti technique (external tumoral border assessment before complete excision) should be considered for EMPD tumors that are larger than 8 cm. Their study also highlighted that tumors deeper than 1 mm carry an increased risk of locoregional recurrence, emphasizing depth as 1 of the most critical prognostic factors in EMPD.[50] IHC staining using CK7 is recommended for the histological assessment of MMS tissue specimens in EMPD cases. CK7 aids in identifying tumoral cells at the tumor margin better than other IHC stains, as it is usually positive in EMPD. This approach has been shown to reduce recurrence rates from an average of 8% to 12% in MMS without CK7 to 2.3% with intraoperative CK7.[30][31]

Regarding MCC, a recent retrospective cohort study by Cheraghlou et al reported on the overall survival rates of MCC treated with MMS. The study included 2313 patients—1452 were treated with WLE, 104 with MMS, and the remainder had narrow excisions. MMS resulted in the best overall survival rate of 81.8% at 10 years compared to 60.9% at 10 years for patients treated with WLE.[51] Nonetheless, as mentioned in previous studies by Su et al, Shaikh et al, Pearlman et al, and Uitentuis et al, no statistically significant differences were found in the survival rates of MCC treated with MMS and WLE.[40][42][43][52]

As of today, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) considers MMS a treatment option for MCC, specifically for localized MCC, which is considered a tumor with no evidence of in-transit nodal or distant metastases. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (LNB) should be performed in every case of MCC due to the high risk of occult nodal metastases. Additionally, radiotherapy should be considered in cases of localized MCC under the following circumstances:

- Involvement of lymph nodes or a history of distant lymph node excision

- Risk of aberrant drainage, particularly in tumors located in the head and neck or midline trunk

- Cases of profound immunosuppression.

WLE with margins ranging from 1 to 2 cm can be utilized for these cases as a treatment approach.[53]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

MMS is a surgical technique that has gained relevance over the years for treating UCMs. The UCMs discussed in this activity (cAS, EPC, Paget disease, and MCC) are often diagnosed in advanced stages. This late diagnosis can occur due to the lack of specific clinical characteristics, especially in EPC and cAS, as well as the aggressive behavior and rapid growth leading to early metastatic disease, particularly in MCC cases. Timely surgical treatment using MMS depends on several factors, the most important being accessibility to trained personnel, specifically Mohs surgeons, who can perform intricate and extensive excisions on patients diagnosed with UCMs.

The shortage of surgeons trained to perform MMS worldwide is a known issue. Notably, it is estimated that in 2020, there were 2411 Mohs surgeons in the United States, with a recent significant growth in this area's workforce.[47] However, 94% of these Mohs surgeons practice in metropolitan areas, leaving rural areas underserved.[48] Data on the statistics of Mohs surgeons outside the United States are unavailable in the current literature. However, an equivalent or even higher shortage may be estimated worldwide. This issue transcends all interprofessional healthcare actors, including advanced practitioners, nurses, histology technicians, laboratory staff, and other healthcare professionals who play pivotal roles and, in some scenarios, are not trained to participate in these specialized surgical procedures.

A strategic approach is needed to guarantee collaborative efforts to train MMS-specialized staff. One approach that has countered the lack of trained teams is modifying the traditional technique of MMS. Paraffin-embedded or slow MMS is an excellent option in cases requiring strict tissue sparing due to its location and possible consequences regarding functionality. This technique may also be an option in patients with UCMs where MMS has shown superiority over WLE, such as EPC. In EPC and MCC, where MMS has demonstrated significantly better outcomes compared to WLE, it is frequent that the procedure is not regularly performed due to difficulties accessing trained surgeons.

Modified MMS techniques enable strong partnership opportunities between pathologists, dermatologists with surgical experience, nurses, histology technicians, laboratory staff, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals. Pathologists require expertise in interpreting microscopic margins. Nurses and advanced practitioners should be skilled in perioperative care and wound management. Histology technicians and laboratory staff must have expertise in processing and interpreting histological slides, which is essential for accurate and timely intraoperative decisions. Pharmacists must be adept in medication management, including preoperative and postoperative pharmacotherapy.

Coordinated efforts are essential for comprehensive care. Multidisciplinary team meetings ensure all aspects of patient care are considered. Coordination with primary care physicians and specialists for follow-up and ongoing management supports continuity of care and holistic treatment.

Treatment delays must be avoided at all costs, considering their strong impact on overall survival. Developing individualized treatment plans based on tumor type, location, and patient factors is crucial. Expanding training pathways for Mohs surgeons worldwide is important to ensure adequate, evidence-based, and timely interventions. Broadening the training on MMS to an interprofessional healthcare team secures a route that streamlines the patient's journey from diagnosis through surgery, ensuring comprehensive responses, risk minimization, and prioritization of safety and care quality. Continuous evaluation and adaptation of strategies based on patient response and outcomes ensure optimal care. Implementing quality improvement initiatives based on data and feedback is crucial for continuous improvement in the field of MMS for patients with UCMs.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Porocarcinoma. This image shows atypical poroid cells and ductal structures, characteristic histopathologic features of eccrine-derived porocarcinoma.

Nephron, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Buffo TH, Stelini RF, Serrano JYM, Pontes LT, Magalhães RF, de Moraes AM. Mohs micrographic surgery in rare cutaneous tumors: a retrospective study at a Brazilian tertiary university hospital. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2023 Jan-Feb:98(1):36-46. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2022.01.009. Epub 2022 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 36369200]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDokic Y, Nguyen QL, Orengo I. Mohs micrographic surgery: a treatment method for many non-melanocytic skin cancers. Dermatology online journal. 2020 Apr 15:26(4):. pii: 13030/qt8zr4f9n4. Epub 2020 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 32621679]

Cohen DK, Goldberg DJ. Mohs Micrographic Surgery: Past, Present, and Future. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2019 Mar:45(3):329-339. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001701. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30608296]

Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Reolid A, Brabyn P, Gallo E, Navarro R, Delgado Jiménez Y. Mohs Surgery Outside Usual Indications: A Review. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC. 2020 Dec:28(7):210-214 [PubMed PMID: 33834992]

Charalambides M, Yannoulias B, Malik N, Mann JK, Celebi P, Veitch D, Wernham A. A review of Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer. Part 1: Melanoma and rare skin cancers. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2022 May:47(5):833-849. doi: 10.1111/ced.15081. Epub 2022 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 34939669]

Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Jimenez YD, Reolid A, Sanmartın-Jimenez O, Garces JR, Rodríguez-Prieto MA, Medrano RM, Vilarrasa E, de Eusebio-Murillo E, Redondo P, Ciudad-Blanco C, Morales-Gordillo V, Toll-Abelló A, Artola-Igarza JL, Pacheco MLA, Markixana IA, Fernández RS, Rubio AA, Vázquez-Veiga H, Flórez-Menéndez A, de la Cueva Dobao P, Botella-Estrada R, Garcia-Bracamonte B, Carnero-González L, Ruiz-Salas V, Sánchez-Sambucety P, López-Estebaranz JL, Gil P, Barchino L, Arenal MM, Ocerin-Guerra I, Hueso L, Seoane-Pose MJ, Gonzalez-Sixto B, Cano-Martinez N, Escutia-Muñoz B, Ortiz-Romero PL, Garcia-Doval I, Descalzo MA, REGESMOHS (Registro Español de Cirugía de Mohs). State of the art of Mohs surgery for rare cutaneous tumors in the Spanish Registry of Mohs Surgery (REGESMOHS). International journal of dermatology. 2020 Mar:59(3):321-325. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14732. Epub 2019 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 31777957]

Thomas CJ, Wood GC, Marks VJ. Mohs micrographic surgery in the treatment of rare aggressive cutaneous tumors: the Geisinger experience. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2007 Mar:33(3):333-9 [PubMed PMID: 17338692]

Bi S, Zhong A, Yin X, Li J, Cen Y, Chen J. Management of Cutaneous Angiosarcoma: an Update Review. Current treatment options in oncology. 2022 Feb:23(2):137-154. doi: 10.1007/s11864-021-00933-1. Epub 2022 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 35182299]

Goldberg DJ, Kim YA. Angiosarcoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1993 Feb:19(2):156-8 [PubMed PMID: 8429143]

Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, Ivan D, Aung PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. Journal of clinical pathology. 2017 Nov:70(11):917-925. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2017-204601. Epub 2017 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 28916596]

Holden CA, Spittle MF, Jones EW. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp, prognosis and treatment. Cancer. 1987 Mar 1:59(5):1046-57 [PubMed PMID: 3815265]

Mikhail GR, Kelly AP Jr. Malignant angioendothelioma of the face. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1977 Mar-Apr:3(2):181-3 [PubMed PMID: 325048]

Muscarella VA. Angiosarcoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1993 Dec:19(12):1132-3 [PubMed PMID: 8282917]

Wollina U, Koch A, Hansel G, Schönlebe J, Kittner T, Pabst F, Haroske G, Nowak A. A 10-year analysis of cutaneous mesenchymal tumors (sarcomas and related entities) in a skin cancer center. International journal of dermatology. 2013 Oct:52(10):1189-97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05484.x. Epub 2013 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 23829640]

Wittenberg GP, Robertson DB, Solomon AR, Washington CV. Eccrine porocarcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: A report of five cases. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 1999 Nov:25(11):911-3 [PubMed PMID: 10594609]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, Baum CL. Treatment of Porocarcinoma With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2016 Jun:42(6):745-50. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000763. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27176862]

Xu YG, Aylward J, Longley BJ, Hinshaw MA, Snow SN. Eccrine Porocarcinoma Treated by Mohs Micrographic Surgery: Over 6-Year Follow-up of 12 Cases and Literature Review. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2015 Jun:41(6):685-92. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000382. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25984905]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVleugels FR, Girouard SD, Schmults CD, Ng AK, Russell SE, Wang LC, Buzney EA. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Jul 20:30(21):e188-91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.6843. Epub 2012 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 22689795]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceD'Ambrosia RA, Ward H, Parry E. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the eyelid treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2004 Apr:30(4 Pt 1):570-1 [PubMed PMID: 15056155]

Lorente-Luna M, Jiménez Blázquez E, Sánchez Herreros C, Cuevas Santos J. Eccrine Carcinoma: The Role of Mohs Micrographic Surgery and a Review of the Literature. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2016 Jan-Feb:107(1):73-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2015.03.018. Epub 2015 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 26233269]

Wildemore JK, Lee JB, Humphreys TR. Mohs surgery for malignant eccrine neoplasms. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2004 Dec:30(12 Pt 2):1574-9 [PubMed PMID: 15606845]

Tolkachjov SN. Adnexal Carcinomas Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Comprehensive Review. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2017 Oct:43(10):1199-1207. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001167. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28445202]

Tidwell WJ, Mayer JE, Malone J, Schadt C, Brown T. Treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: a cases series and literature review. International journal of dermatology. 2015 Sep:54(9):1078-83. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12997. Epub 2015 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 26205087]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSong SS, Wu Lee W, Hamman MS, Jiang SI. Mohs micrographic surgery for eccrine porocarcinoma: an update and review of the literature. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2015 Mar:41(3):301-6. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000286. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25742554]

Le NS, Janik S, Liu DT, Grasl S, Faisal M, Pammer J, Schickinger-Fischer B, Hamzavi JS, Seemann R, Erovic BM. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the head and neck: Meta-analysis of 120 cases. Head & neck. 2020 Sep:42(9):2644-2659. doi: 10.1002/hed.26178. Epub 2020 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 32314845]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYavel R, Hinshaw M, Rao V, Hartig GK, Harari PM, Stewart D, Snow SN. Hidradenomas and a hidradenocarcinoma of the scalp managed using Mohs micrographic surgery and a multidisciplinary approach: case reports and review of the literature. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2009 Feb:35(2):273-81. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34424.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19215270]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRubenzik M, Keller M, Humphreys T. Mohs micrographic surgery for hidradenocarcinoma on a rhinophymatous nose: a histologic conundrum. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2010 Dec:36(12):2075-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01787.x. Epub 2010 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 21044227]

Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Hochwalt PC, Camilleri MJ, Arpey CJ, Brewer JD, Otley CC, Roenigk RK, Baum CL. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of hidradenocarcinoma: the Mayo Clinic experience from 1993 to 2013. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2015 Feb:41(2):226-31. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000242. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25627632]

Lee KY, Roh MR, Chung WG, Chung KY. Comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide excision for extramammary Paget's Disease: Korean experience. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2009 Jan:35(1):34-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34380.x. Epub 2008 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 19018812]

Brough K, Carley SK, Vidal NY. The treatment of anogenital extramammary Paget's disease as part of a multidisciplinary approach: The use of Mohs surgery moat method with CK7. International journal of dermatology. 2022 Feb:61(2):238-245. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15847. Epub 2021 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 34435670]

Bruce KH, Kilts TP, Lohman ME, Vidal NY, Fought AJ, McGree ME, Keeney GL, Baum CL, Brewer JD, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Cliby WA. Mohs surgery for female genital Paget's disease: a prospective observational trial. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2023 Dec:229(6):660.e1-660.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2023.08.018. Epub 2023 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 37633576]

Chang MS, Mulvaney PM, Danesh MJ, Feltmate CM, Schmults CD. Modified peripheral and central Mohs micrographic surgery for improved margin control in extramammary Paget disease. JAAD case reports. 2021 Jan:7():71-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.11.002. Epub 2020 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 33354612]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceO'Connor WJ, Lim KK, Zalla MJ, Gagnot M, Otley CC, Nguyen TH, Roenigk RK. Comparison of mohs micrographic surgery and wide excision for extramammary Paget's disease. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2003 Jul:29(7):723-7 [PubMed PMID: 12828695]

Hendi A, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Extramammary Paget's disease: surgical treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004 Nov:51(5):767-73 [PubMed PMID: 15523356]

Yuan X, Xue R, Cao X. Network meta-analysis of treatments for perineal extramammary paget's disease: Focusing on performance of recurrence prevention. PloS one. 2023:18(11):e0294152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294152. Epub 2023 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 37956192]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTran DC, Ovits C, Wong P, Kim RH. Mohs micrographic surgery reduces the need for a repeat surgery for primary Merkel cell carcinoma when compared to wide local excision: A retrospective cohort study of a commercial insurance claims database. JAAD international. 2022 Dec:9():97-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2022.08.009. Epub 2022 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 36248207]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNguyen BJ, Meer EA, Bautista SA, Kim DH, Etzkorn JR, McGeehan B, Miller CJ, Briceno CA. Mohs Micrographic Surgery for Facial Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Journal of cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2023 Jan-Feb:27(1):28-33. doi: 10.1177/12034754221143080. Epub 2022 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 36471622]

Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, Mostaghimi A, Wang LC, Peñas PF, Nghiem P. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008 Mar:58(3):375-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18280333]

Moore KJ, Thakuria M, Ruiz ES. No difference in survival for primary cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2023 Aug:89(2):254-260. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.042. Epub 2023 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 37121483]

Shaikh WR, Sobanko JF, Etzkorn JR, Shin TM, Miller CJ. Utilization patterns and survival outcomes after wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery for Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States, 2004-2009. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 Jan:78(1):175-177.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.049. Epub 2017 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 28989113]

Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, Zitelli JA. Mohs surgery for early-stage Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) achieves local control better than wide local excision ± radiation therapy with no increase in MCC-specific death. International journal of dermatology. 2021 Aug:60(8):1010-1012. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15533. Epub 2021 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 33760227]

Su C, Bai HX, Christensen S. Relative survival analysis in patients with stage I-II Merkel cell carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery or wide local excision. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2023 Mar:88(3):e131-e132. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.057. Epub 2018 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 29787844]

Pearlman RL, O'Hern KJ, Demer AM, Zeng C, Liszewski W. Survival outcomes after Mohs micrographic surgery are equivalent to wide local excision for treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Archives of dermatological research. 2023 Dec:315(10):3003-3004. doi: 10.1007/s00403-023-02724-0. Epub 2023 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 37819603]

Ronchi A, Cozzolino I, Zito Marino F, De Chiara A, Argenziano G, Moscarella E, Pagliuca F, Franco R. Primary and secondary cutaneous angiosarcoma: Distinctive clinical, pathological and molecular features. Annals of diagnostic pathology. 2020 Oct:48():151597. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2020.151597. Epub 2020 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 32829071]

Pawlik TM, Paulino AF, McGinn CJ, Baker LH, Cohen DS, Morris JS, Rees R, Sondak VK. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: a multidisciplinary approach. Cancer. 2003 Oct 15:98(8):1716-26 [PubMed PMID: 14534889]

Carrasquillo OY, Cancel-Artau KJ, Ramos-Rodriguez AJ, Cruzval-O'Reilly E, Merritt BG. Mohs Micrographic Surgery Versus Wide Local Excision in the Treatment of Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2022 Feb 1:48(2):176-180. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003331. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34889215]

Sedghi T, Gronbeck C, Feng H. Comparison of Socioeconomic and Demographic Characteristics of Counties With and Without Mohs Micrographic Surgeons: A Cross-Sectional Medicare Analysis. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2021 Dec 1:47(12):1655-1657. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003274. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34818277]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFeng H, Belkin D, Geronemus RG. Geographic Distribution of U.S. Mohs Micrographic Surgery Workforce. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2019 Jan:45(1):160-163. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001506. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29620564]

Cortez JL, Elwood H, Matsumoto A. Atypical vascular lesions cleared with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD case reports. 2024 Feb:44():41-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.11.026. Epub 2023 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 38292578]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceO'Connor EA, Hettinger PC, Neuburg M, Dzwierzynski WW. Extramammary Paget's disease: a novel approach to treatment using a modification of peripheral Mohs micrographic surgery. Annals of plastic surgery. 2012 Jun:68(6):616-20. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31821b6c7b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21629074]

Cheraghlou S, Doudican NA, Criscito MC, Stevenson ML, Carucci JA. Overall Survival After Mohs Surgery for Early-Stage Merkel Cell Carcinoma. JAMA dermatology. 2023 Oct 1:159(10):1068-1075. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2822. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37610773]

Uitentuis SE, Bambach C, Elshot YS, Limpens J, van Akkooi ACJ, Bekkenk MW. Merkel Cell Carcinoma, the Impact of Clinical Excision Margins and Mohs Micrographic Surgery on Recurrence and Survival: A Systematic Review. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2022 Apr 1:48(4):387-394. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003402. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35165221]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoyer JD, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG, D'Angelo G. Local control of primary Merkel cell carcinoma: review of 45 cases treated with Mohs micrographic surgery with and without adjuvant radiation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002 Dec:47(6):885-92 [PubMed PMID: 12451374]