Anatomy, Head and Neck, Medial (Internal) Pterygoid Nerve

Anatomy, Head and Neck, Medial (Internal) Pterygoid Nerve

Introduction

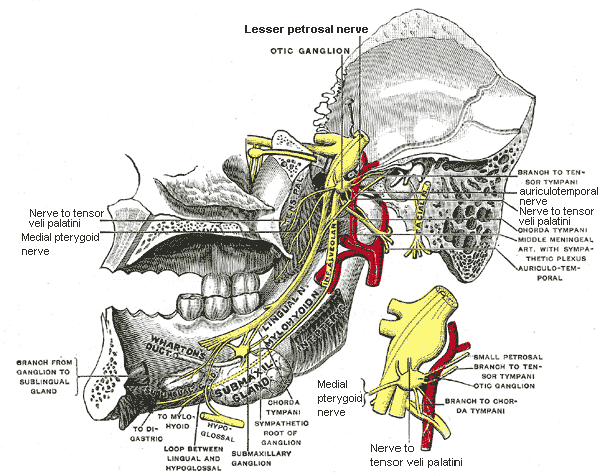

The medial pterygoid nerve is also referred to as the internal pterygoid nerve. It is a slender branch originating from the mandibular division of the V cranial nerve (trigeminal nerve), which enters the deep surface of the medial pterygoid muscle and gives off one or two filaments to the otic ganglion. It innervates the medial pterygoid muscle, tensor tympani muscle, and the tensor veli palatine muscle.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The trigeminal nerve's motor and sensory root exits the cranial cavity through the foramen ovale where they unite and reach the infratemporal fossa. The mandibular nerve then passes between two muscles (tensor veli palatini muscle and lateral pterygoid muscle) and gives off two branches (meningeal branch and the nerve to medial pterygoid muscle) after which it branches into anterior and posterior into divisions.[2] The nerve to medial pterygoid is given off from the medial surface of the mandibular nerve. It travels through the otic ganglion (without synapsing) and gives motor innervation to the medial pterygoid muscle. It enters the muscle either from the upper part of the posterior margin or from the medial surface of the superior-posterior part of the muscle. During its course, it innervates to the tensor tympani muscle and tensor veli palatini muscle. Among all the muscles of the soft palate, tensor veli palatini is the only muscle that is not innervated by the pharyngeal plexus.

Embryology

The formation of the branchial arch system begins in the fourth week of intrauterine life. It consists of paired arches six in number and decreasing in size from cranial to caudal. Each of the branchial arches consists of four essential tissue components (cartilage, artery, nerve, and muscle) that serve as building blocks for the head and neck region. The nerve of the first branchial arch contains motor neurons, also called branchiomotor neurons, innervates the striated skeletal muscles. The motor neurons of the trigeminal nerve derive from the first branchial arch. Hence, the nerve to medial pterygoid, which is a branch of the trigeminal nerve also derives from the first branchial arch.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The maxillary artery supplies the medial pterygoid muscle through its pterygoid branches and by the facial artery through its muscular branches. The tensor veli palatini receives supply from the ascending palatine and accessory meningeal arteries. The tensor tympani muscle receives its arterial supply from the superior tympanic artery, which is a branch of the middle meningeal artery. All three of these muscles receive their innervation from the medial pterygoid nerve.

Nerves

At the mid-pontine level, medial to the sensory nucleus, lies the motor nucleus of the trigeminal nerve. It contains gamma motor neurons (branchiomotor neurons) and the cell bodies of multipolar alpha neurons. The branchiomotor neurons give rise to motor fibers which, after exiting from the pons, form motor root of the trigeminal nerve. After formation, the motor root joins the sensory root just outside the skull and forms the mandibular trunk. The motor root via its various branches provides special visceral efferent (branchiomotor) innervation to various muscles, including medial pterygoid, tensor tympani, and tensor veli palatini muscles.

Muscles

The nerve to medial pterygoid is responsible for innervation and functioning of three muscles (medial pterygoid muscle, tensor tympani, and tensor veli palatine muscle). The medial pterygoid muscle when contracts bilaterally along with lateral pterygoid muscle lead to protrusion of the jaw. This muscle on unilateral contraction along with lateral pterygoid muscle of the same side leads to lateral movement of the jaw to the contralateral side. Also, the muscle functions to elevate the mandible along with the masseter and temporalis muscles.[4]

The activation of the tensor veli palatini muscle tenses the soft palate. During swallowing, this movement is useful as it assists the levator veli palatini muscle in elevating the soft palate, thereby, preventing the entry of food into the nasopharynx. Also, it functions to open the auditory tube (Eustachian tube) to equalize the air pressure between the nasopharynx and the middle ear.[5]

The function of the tensor tympani muscle is to dampen vibrations of the malleus bone caused by very loud sounds. Loud sounds produce significant vibrations. When these vibrations enter the ear, tensor tympani muscle contracts, and pulls the malleus medially, thereby, tensing the tympanic membrane and reducing vibration in the ear ossicles. This action helps in reducing the amplitude of sounds perceived by the individual.

Physiologic Variants

Effective local anesthesia is achievable by injecting the anesthetic solution into the tissue surrounding the nerve innervating the area treated. In some cases, adequate anesthesia is not attainable. This failure may be due to anatomical anomalies/variations. Thus, thorough knowledge of normal and probable physiologic variants is necessary. Various studies have demonstrated the anatomic variation of the mandibular nerve, but thus far studies have not reported differences, particularly of the nerve to medial pterygoid.

Surgical Considerations

The nerve can suffer damage as a result of trauma or tumor removal. The nerve damage can be of three types. Minimal damage to the nerve is termed neuropraxia, which may occur as a result of indirect pressure (retraction during surgery or edema after surgery). This injury resolves rapidly upon pressure release, or the swelling has subsided. Axonotmesis occurs due to vigorous retraction or compression leading to complete destruction of the axonal conduction and degeneration of the distal portions of the axon, without disruption of the supporting structures. Recovery is dependant on the distance between the site of reinnervation and the damage to the nerve. Neurotmesis occurs as a result of the total disruption of axonal conduction and the supporting structures of the nerve.

Surgical intervention (repair or graft) may be necessary if the nerve injury produces damage which does not recover spontaneously or when the damage leads to loss of function resulting in anesthesia, paraesthesia, or dysaesthesia.

Clinical Significance

The medial pterygoid nerve has been implicated in the temporomandibular joint syndrome and jaw pain. Excess stimulation of the nerve has also been shown to cause trismus. The pain of temporomandibular joint syndrome or trismus may receive therapy with muscle relaxants, analgesics, muscle stretches, or heat. The compression of the nerve to medial pterygoid can induce symptoms of neuropathy.

Fracture of the skull may lead to the unilateral lesion of the branchiomotor fibers supplying the muscles of mastication, which results in a flaccid paralysis with subsequent atrophy of the muscles of mastication of the ipsilateral side. Thus, the effect on the motor fibers to the medial pterygoid muscle via medial pterygoid nerve disrupts its normal functioning, impairing chewing on the lesion side due to muscle paralysis. Damage to the motor fibers that innervate the tensor tympani muscle results in hyperacusis and impaired hearing (particularly difficulty in hearing sounds that are low pitched) on the ipsilateral side.

Neoplastic and infectious processes of the infratemporal fossa can either arise from this area or spread to it from other areas. Symptoms experienced may include trismus and any manifestation of mandibular nerve compression such as paresis of masticatory muscles.

Extrinsic carcinomas or any lesion resulting in obstruction of the foramen ovale result in clinical consequences. Such patients may either present only with the sensation of an enlarged mass on the affected side of the face or may report with facial pain and signs of atrophy of the masticatory muscles.[6]

Lesions in the cavernous sinus can also affect the trigeminal nerve and may lead to asymmetry of the jaw on opening or difficulty during mastication.

Other Issues

Compensation for isolated paralysis of the tensor veli palatini muscle is usually via the action of the levator veli palatini muscle resulting in minimal palatal dysfunction. Aural attenuation is reduced with the loss of function of tensor tympani muscle but is usually adequately compensated by the action of the stapedius muscle as long as there is the preservation of cranial nerve VII.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Huff T, Weisbrod LJ, Daly DT. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 5 (Trigeminal). StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489263]

Kamel HA, Toland J. Trigeminal nerve anatomy: illustrated using examples of abnormalities. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2001 Jan:176(1):247-51 [PubMed PMID: 11133576]

Casale J, Giwa AO. Embryology, Branchial Arches. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860722]

Jain P, Rathee M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Medial Pterygoid Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536196]

Georgakopoulos B, Borger J. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Tensor Veli Palatini Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31335022]

Edwards B, Wang JM, Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. Cranial Nerve Foramina Part I: A Review of the Anatomy and Pathology of Cranial Nerve Foramina of the Anterior and Middle Fossa. Cureus. 2018 Feb 8:10(2):e2172. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2172. Epub 2018 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 29644159]