Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Foot Bones

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Foot Bones

Introduction

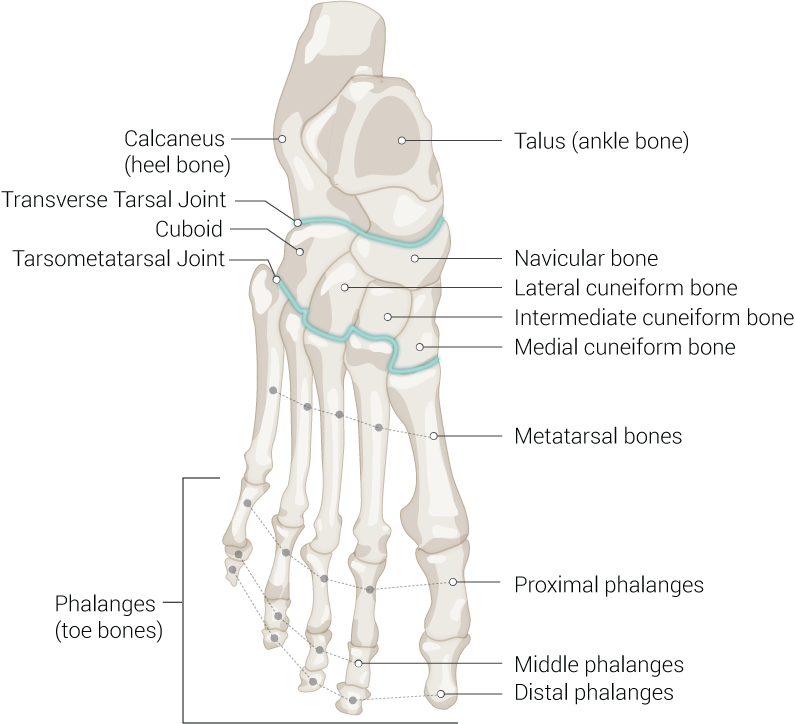

The foot is a complex structure comprised of over 26 bones, 30 joints, numerous tendons, ligaments, and muscles responsible for our ability to stand upright, supporting the weight of the entire body and provides the base for the mechanism for bipedal gait. The foot corresponds to the portion of the lower extremity distal to the ankle and divides into hind, mid and forefoot. The articular surfaces of each bone have a covering of hyaline cartilage, and each joint is invested by a capsule and supported by ligamentous structures. The numerous muscles of the foot are attached to the bones by tendons, which allows the contraction of the muscles to exert force on the osseous structures. This complex anatomy allows the foot to adapt to uneven terrain during heel strike and become a stiff lever for better propulsion during step off. The importance of these structures to activities of daily living not surprisingly results in injury or pain to the feet as a common cause for presentation to the emergency department or primary care clinics. While the ligamentous and soft tissues are essential to foot function, this paper will primarily discuss the osseous structures.[1][2][3][4]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

As previously stated, the foot is comprised of 26 bones distal to the ankle, which can subdivide into the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot.[1] The osseous structures can also be broken down into groups termed tarsal, metatarsal, and phalanges.[5][6][7] The talus and calcaneus, two of the seven tarsal bones, comprise the hindfoot. The hindfoot joins to the more proximal lower extremity at the ankle joint, which is comprised of the tibia, fibula, and talus. The distal tibia (medial malleolus, posterior malleolus, and tibial plafond) and distal fibula (lateral malleolus) form a recess termed the mortis, which articulates with the body of the talus termed the talar dome.[1][4][6][8]

The talus is the second largest tarsal bone. It slopes inferomedially terminating as the convex cartilage covered head that articulates with the navicular. The body of the talus articulates with the calcaneus at the subtalar joint, comprised of multiple facets, posterolateral (posterior facet), middle facet at the sustentaculum tali, located medially, and anterior facet, anteromedially. The superior talar body forms the talar dome and is the articular surface of the tibiotalar joint. The talar neck lies between the body and head of the talus and forms the roof of the tarsal canal that opens laterally as the sinus tarsi. The posterior process of the talus consists of the medial and lateral tubercles with the flexor hallucis longus tendon lying within the groove between them. An elongated lateral tubercle is a normal anatomic variant called a Stieda process. An osseous ridge is ordinarily present at the distal aspect of the talar neck and represents the site of attachment of the joint capsule and ligamentous structures.[1][5][9]

The talus is approximately 60% covered with hyaline cartilage and is devoid of muscular or tendinous attachments. This unique anatomy renders it susceptible to avascular necrosis despite arterial contributions from 3 arteries. The posterior tibial artery supplies the body, and the anterior tibial artery supplies the superior half of the head and neck. Approximately one cm proximal to the division into the medial and lateral plantar arteries, the tarsal canal artery arises from the posterior tibial artery.[1][6][10] The tarsal sinus artery provides the central and lateral two-thirds of the talar body and anastomoses with the artery of the tarsal sinus and gives off the deltoid branches that supply the remaining talus.[11]

Inferior to the talus is the largest tarsal bone, the calcaneus. The calcaneus articulates with the talus superiorly at the anterior, middle, and posterior facets. Each facet is an encapsulated synovial joint with the middle and anterior facets within the same joint capsule. Between the posterior and middle facets, the calcaneal sulcus runs posteromedially and forms the floor of the sinus tarsi. Anteriorly, the calcaneus articulates with the cuboid.[12] The calcaneus is meant to withstand the stresses of weight-bearing, and approximately 50% of our body weight is borne on the subtalar joints and calcaneus, generally split equally between the two feet in the absence of altered weight-bearing/gait. On radiographs, the traction trabeculae radiate from the inferior cortex, and compression trabeculae radiate posteriorly from the anterior and posterior subtalar facets with a small area with relatively few trabeculations called the neutral triangle.[12][13]

The midfoot consists of the cuboid, the navicular, the cuneiforms (medial, middle, lateral), and five of the seven tarsal bones. The navicular is curved concave proximally and convex distally. The concave posterior portion of the navicular receives the ellipsoid shaped talar head forming a ball and socket joint similar to the hip and named coxa pedis.[14] There are three facets along the distal convexity that form articulations with the cuneiforms and one inferolateral facet forming the cuboid articulation. Medially, the posterior tibial tendon attaches to the navicular tuberosity.[7]

The cuboid is a roughly cube-shaped bone that ossifies between the 9th fetal month and six months postnatally. Proximally, it articulates with the calcaneus and distally with the lateral cuneiform and 4 and 5 metatarsals. Rarely, it will articulate with the head of the talus. At the inferolateral margin of the cuboid, there is a sulcus containing the peroneus longus tendon.[1][2][15]

The talonavicular and calcaneocuboid articulations link the hindfoot to the midfoot, collectively called the Chopart joint, named for the famous French surgeon Francois Chopart.[16]

The Cuneiforms articulate proximally with the navicular and distally with the first-third metatarsals and form an arch with a keystone like configuration. The medial cuneiform is the largest and has articulating facets with the first metatarsal distally, a vertical square-shaped facet for the dorsomedial 2nd metatarsal base, laterally with the intermediate or middle cuneiform and proximally with the navicular. The medial cuneiform usually has two ossification centers and ossifies in the 2nd year of life. Importantly, the Lisfranc ligament complex attaches to the distal/lateral aspect of the medial cuneiform running obliquely to the base of the second metatarsal and transmits a large axial load into the second metatarsal during ambulation.[17][18][19]

The middle (intermediate cuneiform) is the smallest of the three cuneiforms. It articulates with the navicular and the second metatarsal, proximally and distally, respectively, as well as the other cuneiforms medially and laterally. Since it is shorter than the adjacent cuneiforms, it forms a mortise and holds the second metatarsal base. The medial cuneiform has one ossification center and ossifies in the third year of life.[17][18][19]

The lateral (third cuneiform) articulates with the cuboid, navicular, third metatarsal, and the middle cuneiform. The plantar surface receives slips from the posterior tibial tendon, and sometimes the flexor hallucis brevis.[19]

The forefoot is composed of the five metatarsals and the 14 phalanges. Each metatarsal can subdivide into three contiguous regions: base, shaft (diaphysis), and head.

The junction of the midfoot to the forefoot is at the tarsometatarsal articulations collectively termed the LisFranc joint, named for the French surgeon Jacques LisFranc de Saint-Martin. The first metatarsal articulates with the medial cuneiform, the second metatarsal with the middle cuneiform, the third with the lateral, and the fourth/fifth with the cuboid joining the midfoot to the forefoot.[20]

The first (greater) metatarsal deserves special attention. At the plantar aspect of the head, there are medial and lateral grooves to accommodate the sesamoid bones. The intersesamoidal ridge separates these grooves. The intersesamoidal ligament links the medial and lateral sesamoid bones. These structures form a portion of the plantar plate complex.[21][22]

The 14 phalanges are analogous to the fingers with two phalanges in the great toe and three in each of the remaining digits. Segmental anomalies are not infrequent.

Functionally, the osseous structures of the foot form three arches. The calcaneus, cuboid, fourth and fifth rays form the rigid lateral arch. The medial arch can dynamically vary in shape, allowing for uneven terrain and has the medial three rays, cuneiforms, navicular, talus, and calcaneus. Finally, the transverse arch runs obliquely along the tarsometatarsal joints.[19]

Seven Tarsal Bones

- Cuboid bone

- Calcaneus or heel bone

- Three cuneiforms (medial, middle and lateral)

- Navicular bone

- The talus bone which is just below the ankle joint

Five metatarsal bones: number 1 to 5 medial to lateral

Fourteen Phalanges

- The first digit has two phalanges.

- The second through fifth digits each have three phalanges

Sesamoid Bones

- The foot also has sesamoid bones that help improve stability and function. The two sesamoid bones are near the first metatarsal bone, where it connects to the big toe. Both sesamoids are within the tendon of flexor hallucis brevis. One sesamoid is usually located on the lateral aspect of the first metatarsal, whereas the other one is often on the medial side. In some individuals, only a single sesamoid may be present near the first metatarsal phalangeal joint.

Foot compartments

- The forefoot contains the phalanges and metatarsals.

- The midfoot consists of the five tarsal bones, three cuneiforms, the navicular, and the cuboid.

- The hindfoot is composed of two tarsal bones, the calcaneus and the talus.

Foot Joints (major)

- Subtalar: articulation between the talus and calcaneus comprised of 6 facets, three on each bone, divided into two joints, anterior (anterior and middle facets) and posterior.[23]

- Chopart: Also known as the midtarsal joint. Joins the hindfoot to the midfoot. It is made up of the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid articulations. Named for the French surgeon Francois Chopart.[16]

- LisFranc: Junction of the mid and forefoot. It is comprised of the tarsometatarsal joints. Named for the French surgeon Jacques LisFranc de Saint-Martin.[20]

- Metatarsophalangeal: The articulations and associated connective tissues are commonly referred to as plantar plates. Injury to the first metatarsophalangeal joint is called turf toe.[22][24]

Embryology

During the fourth through eighth weeks of gestation, the appendicular skeleton develops beginning as ventrolateral swellings of mesenchymal cells covered in ectoderm progressing to limb buds than to fetal extremities. The mesenchymal cells develop into the skeleton, muscles, tendons, and ligaments, while the ectoderm gives rise to the skin. Development progresses in a proximal to distal, anterior to posterior and dorsal to ventral direction with the foot appearing at approximately 4.5 weeks. Ossification centers form by week nine and continue to develop throughout gestation. Some of the foot bones are cartilaginous at birth and ossify during infancy and childhood, as described above.[25][26][27]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The anterior and posterior tibial arteries perfuse the foot. The anterior tibial artery bifurcates, becoming the dorsalis pedis along the dorsal/medial aspect of the foot and the lateral tarsal artery. Together these vessels supply perfusion to the dorsal foot. Distally these vessels converge, forming the transversely running arcuate artery. The posterior tibial artery is palpable at the level of the medial malleolus posteriorly in the region of the proximal tarsal tunnel. It courses anteriorly along the medial aspect of the ankle and plantar hindfoot giving off the artery of the tarsal canal before forming the medial and lateral plantar arteries. The medial and lateral plantar arteries anastomose distally as the transversely running deep plantar arch. Terminal branches of the arcuate and deep plantar arch perfuse the toes. The fibular or peroneal artery runs along the posterior/lateral ankle and hindfoot. There are communicating arteries and anastomosis between the branches of the anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and fibular arteries providing collateral circulation.[1][28][29]

Nerves

Branches of the saphenous, superficial fibular, deep fibular, medial plantar, lateral plantar, and calcaneal nerves are responsible for innervation of the foot.[1]

Sensation to the medial ankle and foot derives from the saphenous nerve, a branch of the femoral nerve. This nerve can sometimes suffer an injury during Achilles tendon repair resulting in pain and burning sensation in the region of the medial hindfoot.[1]

The common fibular nerve divides into the superficial and deep fibular nerves near the level of the knee. The superficial fibular nerve is a terminal branch of the common fibular nerve supplying sensation to the majority of the dorsal foot. The deep fibular nerve innervates the extensor digitorum brevis and extensor hallucis brevis muscles as well as providing sensation to the first web space (between first and second digits).[30]

The tibial nerve branches into the medial and lateral plantar nerves at the level of the ankle on the medial side (tarsal tunnel). The medial plantar nerve supplies sensation to the plantar aspect of the first through third digits and medial aspect of the fourth digit. Additionally, it provides motor innervation to the flexor digitorum brevis, flexor hallucis brevis, abductor hallucis brevis, and 1st lumbrical.[30][31] The lateral plantar branch supplies sensation to the lateral plantar aspect of the 4th digit and the entire plantar aspect of the 5th digit. It also provides motor innervation to the quadratus plantae, abductor digiti minimi, and flexor digiti minimi.[31]

The sural nerve is unique in that it arises from both the tibial and common fibular nerves responsible for sensation to the lateral hind and midfoot. Calcaneal branches of both the tibial and sural nerves supply innervation to the heel.[30]

Muscles

The muscles responsible for motor/movement of the foot can categorize into extrinsic (originating outside the foot) and intrinsic (located entirely within the foot). The extrinsic muscles further subdivide into anterior, posterior, and lateral compartments. The intrinsic muscles fall into two categories; dorsal and plantar. The plantar muscles then further divide into four layers.[26]

Extrinsic

- Anterior Compartment

- Anterior tibialis

- Extensor hallucis longus

- Extensor digitorum longus

- Peroneus tertius

- Posterior Compartment

- Superficial

- Gastrocnemius

- Soleus

- Plantaris

- Deep (posterior/medial)

- Posterior tibialis

- Flexor hallucis longus

- Flexor digitorum longus

- Superficial

- Lateral

- Peroneus longus

- Peroneus brevis

Intrinsic

- Dorsal

- Extensor digitorum brevis

- Extensor hallucis brevis

- Dorsal interossei

- Plantar

- First Layer

- Abductor hallucis

- Flexor digitorum brevis

- Abductor digiti minimi

- Second Layer

- Quadratus plantae

- Lumbricals

- Third Layer

- Flexor hallucis brevis

- Adductor hallucis

- Flexor digiti minimi brevis

- Fourth Layer

- Plantar interossei

- First Layer

Physiologic Variants

Accessory Ossicles

There are numerous accessory ossicles of the foot and ankle that can cause or can be confused for pathology. The os trigonum is posterior to the talus and best seen on lateral radiographs. It results from the failure of fusion of the lateral tubercle of the posterior process, an unfused Stieda process. It is reportedly present in about 7 to 25% of the population. It can be associated with posterior ankle impingement, a cause of posterior ankle pain most commonly presenting in ballet dancers and soccer players. During plantar flexion, the os trigonum can get trapped between the calcaneus and talus.[32]

The os peroneum is a sesamoid bone lateral to the cuboid in the peroneus longus tendon and has a prevalence of up to 30%. It is located within the peroneus longus tendon as it extends beneath the cuboid. Pain associated with the os peroneum can be secondary to fracture, avascular necrosis, chronic repetitive trauma, or contusion. Fractures of the os peroneum may be confused for a bipartite os peroneum. A fractured os peroneum can also correlate with peroneus longus tendon rupture.; this can be appreciated on radiographs when the osseous fragments demonstrate separation by more than a few millimeters.[33]

The os naviculare lies along the medial aspect of the midfoot adjacent to the navicular bone. There are three types. Type 1 is a small well-corticated ossified sesamoid bone in the distal posterior tibialis tendon. Type 2 is triangular or semi-spherical shaped and has fibrocartilaginous bridging the pseudoarticulation or synchondrosis to the navicular tuberosity. Type 3 is a prominent navicular tuberosity, also referred to as cornuate navicular. Symptoms may arise from the type 2 ossicle due to shear stresses across the synchondrosis with the navicular. When symptomatic and not responsive to conservative treatment, the os naviculare is excisable, Kinder procedure.

The os intermetatarsum is a pyramidal shaped ossicle that lies between the base of the first and second metatarsal bones along the dorsal aspect of the foot. It is based seen on AP and lateral views of the foot. It can sometimes be mistaken for the fleck sign of a Lisfranc injury. While generally an asymptomatic normal variant, it can also be associated with compression of the deep peroneal nerve.[34]

Coalitions

Tarsal coalitions are the abnormal fusion of at least two bones. They are thought to arise from primitive mesenchymal segmentation abnormalities and may be fibrous or osseous. Taloncalcaneal and calcaneonavicular joint coalitions represent about 90% of all coalitions. Calcanoenavicular coalitions are best seen radiographically on internal oblique views of the foot; a bony bridge is present in an osseous coalition and close proximity of the bones with irregular cortical surfaces seen in fibrous coalition. On the lateral view, calcaneonavicular coalition is visible as an elongation of the anterior process of the calcaneus referred to as the "anteater sign." The middle facet is most commonly affected in talocalcaneal coalition. Talocalcaneal coalition appears as the "C" sign seen on lateral radiographs. The "C" sign is from osseous bridging of the talus and the sustentaculum. Talocalcaneal coalitions can often be challenging to identify on standard radiographs.[35]

Bipartite Bones

Incomplete fusion of ossification centers may result in bipartite bones. Bipartite medial cuneiforms are rare, appearing in approximately 0.3% of the population. The bipartition may be partial or complete, and in many cases, the segments are bound together by cartilage or fibrocartilage. A bipartite medial cuneiform is divided into dorsal and plantar portions by a horizontal synchondrosis. This horizontal division plane gives the "E sign" on sagittal MR images. Bipartite sesamoids are more common and can be mistaken for fractures. These are most commonly encountered involving the os peroneum and hallux sesamoids. Sesamoid fractures can be difficult to distinguish from bipartite morphology. Fractures tend to have jagged, irregular margins, while bipartite sesamoids will have smooth sclerotic margins.[34][36]

Clinical Significance

Fractures

The talar neck has less trabecular bone than the head and body and is relatively weak. The most common mechanism of fracture is via forced dorsiflexion, and the first case series was described in WWI fighter pilots, termed aviator astragalus; 100 years later, they occur mostly from motor vehicle collisions or falls. Talar neck fractures classify according to the Hawkins-Canale system, and there is a strong correlation with fracture classification and avascular necrosis.[6][8]

Lateral talar process fractures are uncommon but may be radiographically occult. The most common mechanism is forced inversion and dorsiflexion and is more common in snowboarders. They commonly present as continued lateral ankle pain located about 1cm inferior and anterior to the fibula. These injuries are frequently misdiagnosed as ligament sprains. Radiographically, the symmetric V shape of the calcaneus demonstrates distortion on the lateral view in cases of a displaced fracture. Though there are several classification systems, McCrory-Bladin is the most common. Non-displaced fractures receive conservative management, and ORIF is used to manage fractures with >2 mm displacement.[6][37]

Calcaneal fractures are historically devastating injuries and are the most common of the tarsal fractures. Fractures occur with increased axial loading and divide into intraarticular and extraarticular fractures. About three-fourths of calcaneal fractures are intraarticular. The intraarticular fracture results in a shear fracture that involves the posterior facet and the compression line fracture that is from wedging of the anterolateral talar process into the angle of Gissane. Extraarticular fractures involve the anterior process, mid-calcaneus (body, sustentaculum tali, peroneal tubercle, and lateral process) and the posterior calcaneus. CT is the preferred modality for characterizing calcaneal fractures, especially for characterizing the extent of involvement of the posterior subtalar joint. Calcaneal fractures are also associated with thoracolumbar spine fractures. Screening for a coexisting back injury is critical clinically. In the setting of back pain, thoracolumbar CT imaging is indicated.[38]

Lisfranc injuries are fracture-dislocation injuries of the tarsometatarsal joints. The Lisfranc ligament complex is made of three bands, the dorsal oblique, plantar oblique, and the interosseous fibers that bind the second metatarsal base to the medial cuneiform. Though the interosseous fibers are the most important, if two of the three bands are disrupted, the second TMT joint is unstable. The injury is relatively common in sports such as football, basketball, and gymnastics. The mechanism is an axial loading of the plantarflexed foot. Patients present with dorsal midfoot swelling and vague midfoot pain. Weight-bearing radiographs are more sensitive, but findings may be subtle such as the "fleck" sign, which is the result of an osseous avulsion fracture. Other radiographic findings include dorsal midfoot soft tissue swelling and widening of the space between the base of the first and second metatarsal bones. Lisfranc injuries can be classified as divergent or homolateral, based on the direction of displacement of the metatarsal bones. Radiographic assessment for Lisfranc injuries should include scrutiny of the alignment of the tarsometatarsal joints, which were described in more detail above.[20]

Bone lesions can categorize as aggressive or non-aggressive based on their pattern of destruction. The Lodwick-Madewell grading system is a method for classifying the aggressiveness of a lesion and has significant prognostic/pathologic concordance. Important imaging features to assess include margins, cortical disruption, associated soft tissue mass, and endosteal scalloping. If a lesion is well-circumscribed with a thin sclerotic margin, it is likely benign. However, if a lesion has a wide zone of transition, poorly defined margins, or cortical disruption, it is highly suspicious for an aggressive process such as malignancy or infection.[39] Patient age is also essential to developing a useful differential as certain processes are more common in specific demographics. For example, Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma are more common in younger patients. Enlarging lesions, lesions with soft tissue components, or lesions larger than 5 cm are more likely to be malignant.[39] The most common benign lesions of the foot are unicameral bone cyst (most common in the calcaneus), enchondroma (most common in the metatarsal), and osteochondroma (most common in the forefoot and ankle). The most common malignant lesions are chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma (common in the calcaneus), and Ewing sarcoma (most common in the mid and hindfoot).[40][41]

Osteonecrosis is the ischemic death of bone and is commonly referred to as avascular necrosis (AVN). Common causes include trauma, corticosteroids, alcoholism, sickle cell disease, and collagen vascular diseases. Some specific areas are worthy of mention. Freiberg infraction involves the metatarsal heads, approximately 68% in the second metatarsal, and approximately 28% in the third metatarsal. Radiographically it may appear as mottled sclerosis, with or with subchondral collapse of the metatarsal head. Freiberg's is more common in women and thought to be secondary to high heeled shoes.[42] Koehler's disease or Muller-Weiss is osteonecrosis of the navicular. It is generally bilateral, and the lateral aspects of the bone are initially involved. Kohler's disease, the pediatric variant, most commonly affects 4- to 6-year-old boys. Osteonecrosis of the talus is most often posttraumatic and may lead to the collapse of the talar dome.[42]

Gout is a metabolic disease that results in monosodium urate crystal deposition. The lower extremities are most frequently involved, classically the great toe where it is called podagra. Osseous erosions can occur anywhere on a bone but are most common intra- and para-articularly. Acute episodes generally resolve in a few days without treatment. Early gout may be radiographically occult, but as the disease progresses, marginal joint erosions with overhanging margins develop. Soft tissue masses termed tophi can be present secondary to uric acid deposition in the soft tissues. Soft tissue tophi are "pseudolesions," which can be mistaken for a malignant process. Generally, the clinical presentation and existence of erosions on images help to arrive and the correct diagnosis and thereby eliminating unnecessary tissue sampling.[43]

Metatarsal stress injuries are common in military recruits, runners, and ballet dancers. Other conditions that alter weight-bearing, such as hallux valgus or low arches, also increase the risk of stress injuries. Additionally, metabolic disorders or vitamin deficiencies may predispose to fractures. Fatigue fractures are caused by repeated stress on healthy bone, and insufficiency fractures are caused by repeated stress on the abnormally weakened bone. These types of injuries are frequently radiographically occult until periosteal reaction or sclerosis is present indicative of the healing process. MR and nuclear medicine bone scans are more sensitive than radiographs and are obtainable if patients fail conservative management. Common locations in the foot and ankle include the calcaneal tuberosity, talar head (subchondral), navicular, the base of the first and fifth metatarsal bones, and the diaphysis to the neck of the second to fourth metatarsal bones.[44]

Sesamoiditis can occur secondary to repetitive injury, fall from heights, or stepping on uneven surfaces. It is best characterized by MR imaging with increased STIR signal but normal T1. The surrounding soft tissues are often inflamed. Osteomyelitis of the foot most often results from penetrating injury or ulceration and is most common in diabetic patients. Radiographs may show osseous destruction but may be negative in early osteomyelitis, and MR imaging is more sensitive. MR imaging of osteomyelitis shows decreased T1 and increased STIR signal.[45][46]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Foot Bones. Anatomy of the foot including talus (ankle bone), navicular bone, lateral cuneiform bone, intermediate cuneiform bone, medial cuneiform bone, metatarsal bones, proximal phalanges, middle phalanges, distal phalanges, phalanges (toe bones), tarsometatarsal joint, cuboid, transverse tarsal joint, and calcaneus (heel bone).

Contributed by Beckie Palmer

References

Ficke J, Byerly DW. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Foot. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536304]

Manganaro D, Dollinger B, Nezwek TA, Sadiq NM. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Joints. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725626]

Stirling P, MacKenzie SP, Maempel JF, McCann C, Ray R, Clement ND, White TO, Keating JF. Patient-reported functional outcomes and health-related quality of life following fractures of the talus. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2019 Jul:101(6):399-404. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2019.0044. Epub 2019 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 31155885]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrockett CL, Chapman GJ. Biomechanics of the ankle. Orthopaedics and trauma. 2016 Jun:30(3):232-238 [PubMed PMID: 27594929]

Melenevsky Y, Mackey RA, Abrahams RB, Thomson NB 3rd. Talar Fractures and Dislocations: A Radiologist's Guide to Timely Diagnosis and Classification. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2015 May-Jun:35(3):765-79. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015140156. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25969933]

Russell TG, Byerly DW. Talus Fracture. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969509]

Prapto D, Dreyer MA. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Navicular Bone. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613455]

Shamrock AG, Byerly DW. Talar Neck Fractures. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194455]

Resnick D. Talar ridges, osteophytes, and beaks: a radiologic commentary. Radiology. 1984 May:151(2):329-32 [PubMed PMID: 6709899]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMulfinger GL, Trueta J. The blood supply of the talus. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1970 Feb:52(1):160-7 [PubMed PMID: 5436202]

Pearce DH, Mongiardi CN, Fornasier VL, Daniels TR. Avascular necrosis of the talus: a pictorial essay. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2005 Mar-Apr:25(2):399-410 [PubMed PMID: 15798058]

Kumar R, Matasar K, Stansberry S, Shirkhoda A, David R, Madewell JE, Swischuck LE. The calcaneus: normal and abnormal. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1991 May:11(3):415-40 [PubMed PMID: 1852935]

Daftary A, Haims AH, Baumgaertner MR. Fractures of the calcaneus: a review with emphasis on CT. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2005 Sep-Oct:25(5):1215-26 [PubMed PMID: 16160107]

Walter WR, Hirschmann A, Alaia EF, Tafur M, Rosenberg ZS. Normal Anatomy and Traumatic Injury of the Midtarsal (Chopart) Joint Complex: An Imaging Primer. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2019 Jan-Feb:39(1):136-152. doi: 10.1148/rg.2019180102. Epub 2018 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 30500305]

Gill M, Vilella RC. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Foot Cuboid Bone. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751102]

Walter WR, Hirschmann A, Tafur M, Rosenberg ZS. Imaging of Chopart (Midtarsal) Joint Complex: Normal Anatomy and Posttraumatic Findings. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2018 Aug:211(2):416-425. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.19310. Epub 2018 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 29927330]

Cenatiempo M, Buzzi R, Bianco S, Iapalucci G, Campanacci DA. Tarsometatarsal joint complex injuries: A study of injury pattern in complete homolateral lesions. Injury. 2019 Jul:50 Suppl 2():S8-S11. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.01.038. Epub 2019 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 30745126]

Mason L, Jayatilaka MLT, Fisher A, Fisher L, Swanton E, Molloy A. Anatomy of the Lateral Plantar Ligaments of the Transverse Metatarsal Arch. Foot & ankle international. 2020 Jan:41(1):109-114. doi: 10.1177/1071100719873971. Epub 2019 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 31502882]

McKeon PO, Hertel J, Bramble D, Davis I. The foot core system: a new paradigm for understanding intrinsic foot muscle function. British journal of sports medicine. 2015 Mar:49(5):290. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092690. Epub 2014 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 24659509]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSiddiqui NA, Galizia MS, Almusa E, Omar IM. Evaluation of the tarsometatarsal joint using conventional radiography, CT, and MR imaging. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2014 Mar-Apr:34(2):514-31. doi: 10.1148/rg.342125215. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24617695]

Nery C, Baumfeld D, Umans H, Yamada AF. MR Imaging of the Plantar Plate: Normal Anatomy, Turf Toe, and Other Injuries. Magnetic resonance imaging clinics of North America. 2017 Feb:25(1):127-144. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2016.08.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27888844]

Linklater JM. Imaging of sports injuries in the foot. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2012 Sep:199(3):500-8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8547. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22915389]

Resnick D. Radiology of the talocalcaneal articulations. Anatomic considerations and arthrography. Radiology. 1974 Jun:111(3):581-6 [PubMed PMID: 4828991]

Yamada AF, Crema MD, Nery C, Baumfeld D, Mann TS, Skaf AY, Fernandes ADRC. Second and Third Metatarsophalangeal Plantar Plate Tears: Diagnostic Performance of Direct and Indirect MRI Features Using Surgical Findings as the Reference Standard. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2017 Aug:209(2):W100-W108. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17276. Epub 2017 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 28570126]

Lezak B, Massel DH. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Metatarsal Bones. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751062]

Card RK, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969527]

Marín-Llera JC, Garciadiego-Cázares D, Chimal-Monroy J. Understanding the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms That Control Early Cell Fate Decisions During Appendicular Skeletogenesis. Frontiers in genetics. 2019:10():977. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00977. Epub 2019 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 31681419]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBasit H, Eovaldi BJ, Sharma S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Peroneal Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855864]

Lezak B, Wehrle CJ, Summers S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Posterior Tibial Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725666]

Tang A, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Nerves. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725977]

Desai SS, Cohen-Levy WB. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Tibial Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725713]

Sellon E, Robinson P. MR Imaging of Impingement and Entrapment Syndromes of the Foot and Ankle. Magnetic resonance imaging clinics of North America. 2017 Feb:25(1):145-158. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2016.08.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27888845]

Hindi HF, Byerly DW. Os Peroneum. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855913]

Chan BY, Markhardt BK, Williams KL, Kanarek AA, Ross AB. Os Conundrum: Identifying Symptomatic Sesamoids and Accessory Ossicles of the Foot. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2019 Aug:213(2):417-426. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.20761. Epub 2019 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 30973781]

Newman JS, Newberg AH. Congenital tarsal coalition: multimodality evaluation with emphasis on CT and MR imaging. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2000 Mar-Apr:20(2):321-32; quiz 526-7, 532 [PubMed PMID: 10715334]

Brookes-Fazakerley SD, Jackson GE, Platt SR. An additional middle cuneiform? Journal of surgical case reports. 2015 Jul 29:2015(7):. pii: rjv076. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjv076. Epub 2015 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 26224890]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWijers O, Posthuma JJ, De Haas MBJ, Halm JA, Schepers T. Lateral Process Fracture of the Talus: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2020 Jan-Feb:59(1):136-141. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2019.02.003. Epub 2019 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 31668959]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBadillo K, Pacheco JA, Padua SO, Gomez AA, Colon E, Vidal JA. Multidetector CT evaluation of calcaneal fractures. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2011 Jan-Feb:31(1):81-92. doi: 10.1148/rg.311105036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21257934]

Caracciolo JT, Temple HT, Letson GD, Kransdorf MJ. A Modified Lodwick-Madewell Grading System for the Evaluation of Lytic Bone Lesions. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2016 Jul:207(1):150-6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14368. Epub 2016 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 27070373]

Azevedo CP, Casanova JM, Guerra MG, Santos AL, Portela MI, Tavares PF. Tumors of the foot and ankle: a single-institution experience. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2013 Mar-Apr:52(2):147-52. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2012.12.004. Epub 2013 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 23333280]

Murai NO, Teniola O, Wang WL, Amini B. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors About the Foot and Ankle. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2018 Nov:56(6):917-934. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2018.06.010. Epub 2018 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 30322490]

Couturier S, Gold G. Imaging Features of Avascular Necrosis of the Foot and Ankle. Foot and ankle clinics. 2019 Mar:24(1):17-33. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2018.10.002. Epub 2018 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 30685010]

Desai MA, Peterson JJ, Garner HW, Kransdorf MJ. Clinical utility of dual-energy CT for evaluation of tophaceous gout. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2011 Sep-Oct:31(5):1365-75; discussion 1376-7. doi: 10.1148/rg.315115510. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21918049]

Gefen A. Biomechanical analysis of fatigue-related foot injury mechanisms in athletes and recruits during intensive marching. Medical & biological engineering & computing. 2002 May:40(3):302-10 [PubMed PMID: 12195977]

Ashman CJ, Klecker RJ, Yu JS. Forefoot pain involving the metatarsal region: differential diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2001 Nov-Dec:21(6):1425-40 [PubMed PMID: 11706214]

Taylor JA, Sartoris DJ, Huang GS, Resnick DL. Painful conditions affecting the first metatarsal sesamoid bones. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1993 Jul:13(4):817-30 [PubMed PMID: 8356270]