Introduction

Hypopigmented macules are one of the most common skin lesions encountered in clinical practice. The word hypopigmentation indicates decreased pigmentation, which means significantly reduced melanin compared to the normal skin. This should not be confused with the word depigmentation, which is an indicator of the complete absence of melanin due to the significant loss of melanocytes. Clinically, it is challenging to differentiate hypopigmented disorders from depigmented disorders.[1]

It is important to understand the difference between these conditions since the treatment and prognosis often differ. Hypomelanosis is often benign, may be associated with the function of internal viscera, and rarely associated with malignancy. One of the frequent reasons to seek treatment is the cosmetic appearance, which can cause stress and social stigma (especially in dark-skinned people) in the patients. Repigmentation can be achieved in some cases by the right diagnosis and prompt treatment. A detailed history, clinical signs along with wood's lamp examination, and dermoscopy help in making the right diagnosis. Apart from these, a skin biopsy histopathological findings provide additional information to understand the underlying pathogenesis. This article briefly reviews the common disease conditions associated with hypopigmented macular lesions (size less than 0.5 cm) and patches (more than 0.5cm). A brief idea of the anatomy of the skin and the mechanism of skin pigmentation is important to understand the pathogenesis and histologic findings of hypopigmentation disorders.

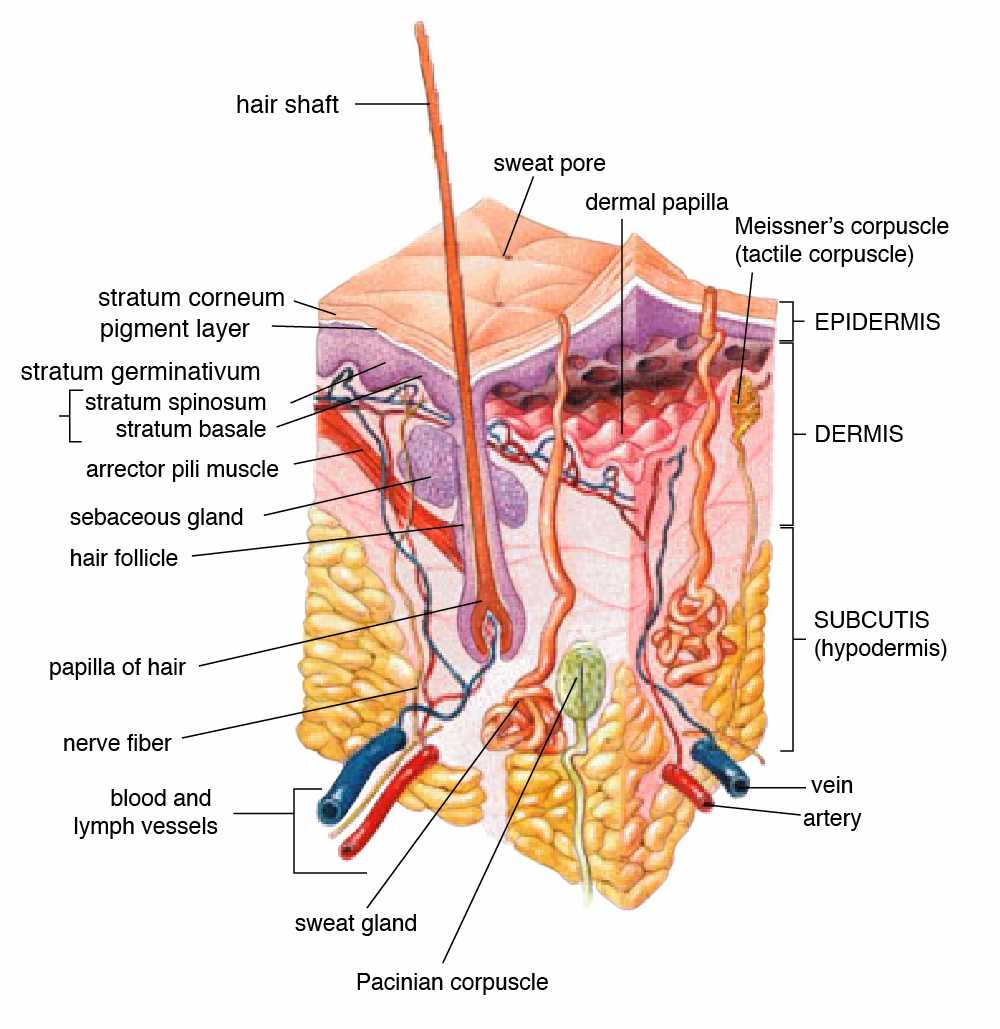

Anatomy of the Skin- Skin is the largest organ in the body and is made up of three layers- epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The epidermis is again divided into five layers. They are Stratum basal (the deepest layer of the epidermis), S.spinosum, S.granulosum, S.lucidum, and S.corneum (most superficial layer of the epidermis; normally, cells in this layer do not contain any nuclei). Stratum lucidum is present only in the areas of thick skin (eg., palms of hand).

Mechanism of skin pigmentation- It is mainly regulated by keratinocytes and melanocytes present in the basal layer of the epidermis. Melanocytes are embryologically derived from neural crest cells, and their migration to skin and hair is regulated by various transcription factors and signaling pathways. Melanocytes produce a brown pigment - melanin, which protects the skin from potentially harmful UV radiation present in sunlight. Exposure to UV light could potentially cause defects in the DNA of keratinocytes. This leads to overexpression of the P53 gene resulting in increased transcription of the POMC gene (proopiomelanocortin), thereby increasing the synthesis of POMC protein. The POMC protein is cleaved into ACTH and alpha MSH. Alpha MSH binds to the G-protein receptor (MC1R) on melanocyte, activates adenyl cyclase, and mitogen-activated protein (MAP). In turn, this results in the production of eumelanin, tyrosinase, and tyrosinase-related protein. The tyrosinase enzyme converts tyrosine into DOPA and melanin.

Tyrosinase is the rate-limiting enzyme for melanogenesis. Melanin is then packed in melanosomes (lysosome-like organelles) and is transferred to keratinocytes through protease-activated receptors. As the skin ages, the keratinocytes move from the basal to superficial layer along with these ingested melanosomes, which give the brownish tint to the skin. There are two kinds of melanin- pheomelanin and eumelanin. Pheomelanin is predominant in fair-skinned people and eumelanin in dark-skinned people. Eumelanin protects the skin against UV radiation better than pheomelanin.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Hypopigmented conditions are mostly acquired, rarely congenital.

Congenital conditions include;

- Albinism- Autosomal recessive inheritance

- Piebaldism- Autosomal dominant inheritance[2]

- Hypomelanosis ito (chromosomal defects)

A few of the etiologies associated with acquired hypopigmented conditions are discussed below;

- Normal aging- Idiopathic guttate melanosis (IGH)

- Environmental factors (cumulative sun exposure and microtrauma)- IGH

- Nutritional deficiencies- Kwashiorkor (a severe protein malnutrition condition), vitamin B12 deficiency, copper and iron deficiency

- Inflammatory causes- Pityriasis alba (association with atopic dermatitis)

- Vascular causes (venous congestion)- Bier's spots

- Autoimmune causes- Vitiligo, hypopigmented sarcoidosis

- Infectious causes- 1. fungal by Malassezia species- Pityriasis versicolor, 2. bacterial infection by Propionibacterium acne- Progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), Mycobacterium leprae - Leprosy, and Treponema pallidum - Leukoderma syphiliticum, 3. protozoal by post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, 4. postviral exanthem- Eruptive hypomelanosis

- Chemical inflammation- Lead-based cosmetics, skin bleaching agents like hydroquinone, etc

- Post-inflammatory changes- Secondary to any cutaneous inflammatory conditions (eg., lichen striatus, atopic dermatitis), infections (eg., Tinea versicolor, Herpes Zoster, Syphilis), procedures (eg., cryotherapy, dermabrasion) and miscellaneous causes (eg., burns) [3]

- Malignancy- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, the tumor of follicular infundibulum

- Inherited conditions- Ash leaf spots in tuberous sclerosis

Epidemiology

Hypopigmentation macules are very common (in both children and adults), seen in at least 1 out of 20 people.[4][5] The prevalence of various hypomelanotic conditions depends on patient demographics (age, sex, race), geography, family history, and exposure to environmental factors. For example, P. alba is more prevalent (90%) in the pediatric age group(<16 years), P.versicolor more prevalent in adolescents and young adults, IGH is more prevalent (80% to 87%) in the adult age group (> 40 years), and vitiligo can affect anyone from a toddler to elderly people. P.alba shows slight male predominance, whereas P.versicolor affects both sexes equally.

Hansen's disease is more prevalent in developing countries; more than 75% of leprosy cases in the United States are contributed by immigrants. P.alba is often seen in patients with a family history of atopic dermatitis.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenic mechanism is different in various conditions associated with hypomelanosis. Pathophysiology for a few are discussed below:

1. Pityriasis alba - There is no proven cause identified. Most studies suggest that UV light exposure has a causal relationship. UV radiation affects the function of active melanocytes, thereby altering the synthesis of melanin.

2. Pityriasis/Tinea versicolor - Malassezia is a common commensal of healthy skin transforms into a pathogenic (filamentous) form. Factors that contribute to pathogenic conversion are genetic predisposition, environment conditions (heat, humidity), oily skin, and application of oily creams or lotions.[6] The pathogenic form metabolizes fatty acids on the skin, release azelaic acid and other metabolites. Azelaic acid inhibits the dopa-tyrosinase enzyme, which is the rate-limiting enzyme for melanin synthesis, thereby causing hypopigmentation skin lesions.

3. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis [IGH] - The predominant involvement of sun-exposed areas in IGH raises suspicion of UV light as a primary factor affecting melanin synthesis. Few studies also suggest that IGH has a positive association with HLA DQ3, repeated microtrauma, and autoimmunity.[7] Histopathologic correlation like structural abnormalities of melanocytes, defective keratinocyte uptake, and decrease melanosomes help to understand the pathogenic mechanisms involved in developing hypopigmented macules in IGH.[8]

4. Vitiligo - Multiple pathogenic mechanisms were proposed. T cell-induced melanocyte apoptosis, autoantibodies to components of melanocytes leads to decreased melanin production and thereby causing hypopigmentation.

5. Albinism - This is an autosomal recessive disease, associated with a deficiency of tyrosinase enzyme (the rate-limiting enzyme in melanin synthesis). The severity of clinical features depend on the mutation involved.[9]

6. Halo nevus - Based on histopathological findings, the abundance of Langerhans cells in the area of the lesion is responsible for hypopigmentation. This condition is benign. Some also argue that the halo nevus condition has an association with vitiligo.[9]

8. Post-inflammatory hypopigmentation - This condition is associated with trauma or exposure to chemicals (cleaning agents, chemicals used to remove tattoos, or for cosmetic purposes). The pathogenesis in this condition is related to melanocyte injury resulting in decreased melanin, which in turn causes hypopigmented or depigmented patches. Post-inflammatory conditions can also be associated with hyperpigmentation.

9. Ash leaf spots - These are the cutaneous findings associated with the neurocutaneous disorder. The presence of three or more ash leaf spots should raise suspicion of tuberous sclerosis.

Histopathology

Histopathological findings are occasionally required for diagnosis. They are useful in evaluating the underlying pathophysiology to determine the right diagnosis. It gives an overview of the presence of melanin, melanocytes, changes in epidermal cells like acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, epidermotropism, spongiosis, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, etc. A few of the classic histopathologic features of hypomelanotic conditions are spaghetti meatball appearance in

Tinea versicolor, pautrier microabscesses in HMF, absence of melanocytes in vitiligo., decrease in DOPA positive melanocytes (active melanocytes) in IGH, dilated follicular infundibula connected to each and to the overlying epidermis in the tumor of the follicular infundibulum (infundibulomatosis), and many more. Histopathological findings are also useful to determine the status of the disease, e.g., active or inactive stage of vitiligo.[10][11] Immunohistochemical staining can be used to evaluate the peculiar characteristics of cells (like CD4 and CD8 infiltration) in the epidermis.

History and Physical

The differentiation of various hypopigmented conditions is not always possible solely based on the clinical findings of the lesion. A detailed history of the patient, including personal, occupational, and family history, gives a clue about the etiology and severity (inherited/ acquired, benign/malignant) of the condition. The patients, at times, may have extracutaneous signs and symptoms, and a complete physical examination from head to toe is vital to make the right diagnosis. The following questionnaire and examination findings may be useful to evaluate the patients with hypopigmentation macules.

1. Is the skin lesion present since birth or acquired?

2. If acquired, is it sudden or gradual in onset?

3. Any history of prior inflammation, or exposure to chemical substances?

4. Is the hypopigmentation localized or diffuse?

5. Location of the lesions - which areas are predominantly affected? (sun-exposed areas, or body-folds like axilla, or under the breast)

6. Characters of lesion - this includes:

- Size of the lesions

- Margins-well circumscribed or ill-defined

- Appearance- scaly/non-scaly

- Pattern of distribution

- Unilateral or bilateral

- Stable or progressive

- Any coalesce of lesions

- Any changes in color

- Any history of pruritus or signs of excoriation

- Any history of prior inflammation, or exposure to chemical substances?

- Any change in the characteristics of lesions due to weather conditions?

- Surrounding skin characteristics

Evaluation

A systematic approach should be followed to reach the right diagnosis.

- Wood's lamp examination - This is used for better visualization of skin lesions to differentiate pigment abnormalities (especially hypopigmented lesions from depigmented lesions). This is done in a darkened room using a Wood's lamp that emits long-wave UVA (Ultraviolet light A) with a wavelength of approximately 365 nm.[12] The light source should be held at 4 to 5 inches away from the skin surface. Normal skin does not fluoresce. Depigmented lesions (eg., vitiligo) and hypopigmented lesions with decreased melanin production are markedly enhanced, appear bright white whereas, hypopigmented lesions with normal melanin (IGH, PMH) are not accentuated. A few of the characteristic features of Wood's lamp examination are orange fluorescence in P. versicolor, red fluorescence localized to follicles in PMH, bright blue-white fluorescence in Vitiligo, etc.[13] Wood's lamp is also used to perform a meticulous search for the presence of more hypopigmented lesions when a patient presents with a single lesion.[14]

- Dermatoscopy - This refers to the skin examination using a skin surface microscope, especially used to evaluate pigment abnormalities of the skin. Dermoscopic findings give details about- nature of pigmentation, edges of the lesion (well-defined/ ill-defined), the appearance of lesions (scaly/ non-scaly), perifollicular hyperpigmentation (seen in Vitiligo), presence of telangiectasia, and characteristics of the surrounding skin.[15]

- KOH mount of skin scrapings - This test is useful to quickly identify fungal infections like Tinea versicolor (Spaghetti and meatball appearance of hyphae) in outpatient settings. The specimen is prepared by adding one drop of 10% KOH to skin scrapings and examining it under the microscope.[16]

- Skin Biopsy - Although skin biopsy gives accurate diagnosis in most conditions, this is not routinely performed; it is used only when the diagnosis is unclear or suspecting infectious causes like leprosy, sarcoidosis, or underlying malignancy. Tissue biopsy is processed and studied under a microscope using various stains like hematoxyline and eosin, Fontana Masson, or Melanin-A stains. Immunofluorescence studies on the specimen could be performed for the presence of antibodies, and infiltration of lymphocytes into the epidermis, etc.[17]

- Electron Microscopy - This is not commonly available in clinical settings, and physicians should rely on other clinical findings. Electron microscopic study of skin lesion gives an insight into ultrastructural details of the lesion and helps differentiate the causes for hypomelanosis. For example, clinical differentiation of ash leaf spots (ALS), a common presentation in the pediatric age group from nevus depigmentosus (ND), is challenging even based on histopathologic findings. The findings under electron microscopy show a decrease in melanosome transfer to keratinocytes in ND, and reduced size and melanization of melanosomes result in the formation of aggregates in keratinocytes in ALS.[5]

Treatment / Management

The management of hypopigmented macules depends on the underlying pathophysiology. Successful repigmentation is often possible with timely diagnosis, removal of offending agents (chemicals, infectious agents), avoiding exposure to sunlight, using sunscreen, and appropriate therapeutic treatment. Repigmentation might not be possible in the congenital/ inherited conditions (associated with chromosomal defects). Therapeutic treatment helps to fasten the process of repigmentation. Repigmentation is achieved by medications, phototherapy, and surgical procedures.

Medications - There are topical and systemic medications.

- Topical corticosteroids - Low dose corticosteroids are used as first-line drugs in many hypopigmented conditions. They are known to accelerate the repigmentation process. Their use, along with phototherapy, also has great outcomes. Systemic corticosteroids are rarely used to treat hyperpigmentation, for e.g., in vitiligo, to halt the rapid progression of skin lesions.

- Topical calcineurin inhibitors - These are topical immunomodulatory agents (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus), also used as first-line medication. Tacrolimus inhibits the synthesis and release of proinflammatory cytokines, thereby protecting melanocytes from the effects of T-cell and mast-cells. In contrast to topical steroids, tacrolimus does not cause skin atrophy and striae, preferred for treating facial hypomelanosis conditions.

- Vitamin D - The current literature reviews that vitamin D has an association with skin pigmentation. Vitamin D increases melanogenesis by increasing the tyrosinase content in melanocytes by the anti-apoptotic effect.[18]

- Antifungals - These are used in treating Tinea versicolor infection, available in both topical and systemic forms. Topical agents are often used for weeks to months; include selenium sulfide shampoo, 1% or 2% ketoconazole ointment, zinc pyrithione. Oral medications like fluconazole, itraconazole are used for a short duration of therapy.

- Oral isotretinoin- This is used to treat conditions like PMH in which propionibacterium acne is the underlying cause.[13]

- Emollients - Used to provide a soothing effect in pruritic and scaly skin lesions. (B3)

Phototherapy - This includes narrow-band ultraviolet B (NBUVB) and psoralen ultraviolet A (PUVA). NBUVB is superior and preferred over PUVA in treating vitiligo. PUVA has comparatively more adverse effects because of the systemic use of psoralen. PUVA is contraindicated in children and pregnant women.[19](A1)

Surgical Procedures - skin grafting, split skin grafting are practiced in treating some localized depigmented and inherited hypopigmented conditions.

Differential Diagnosis

- Some of the common differential diagnoses for hypopigmented macules include P. alba, P. versicolor, IGH, vitiligo, PMH, post-inflammatory inflammation, and halo nevus.

- P. alba usually is seen in the pediatric age group, patients often have a history of atopic dermatitis, whereas P. versicolor is more prevalent in the adolescent age group, warm and humid conditions, and lesions are predominantly distributed in seborrheic areas (trunk, neck, and arms).[6]

- IGH is more prevalent in the elderly and is hinted by a history of chronic exposure to sunlight and repetitive microtrauma. Lesions usually do not coalesce.

- It is important to differentiate these conditions because the management and prognosis vary. Complete history (family history and any history of autoimmune diseases), physical examination, and areas of distribution of hypopigmented patches help in determining the right diagnosis. Dermoscopy can aid in differentiating vitiligo from other vitiligo-like conditions. Vitiligo patches usually show residual perifollicular pigmentation, which is absent in other conditions. Vitiligo, at times, could be confused with chemical leukoderma and vitiligo-like depigmentation in oncology patients treated with immunotherapy for non-melanoma metastatic cancers.[20]

- Diagnosing hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (HMF) is usually delayed in children (although it is rare), as it is often mistaken with other hypomelanosis conditions like Pityriasis, eczema, vitiligo, PMH, etc. A high rate of suspicion and skin biopsy is required for accurate diagnosis of HMF, and tumor of follicular infundibulum.[21]

Prognosis

Most of the conditions associated with hypopigmentation are benign in nature and have an excellent prognosis. Often, repigmentation can be achieved with prompt diagnosis and treatment. However, the prognosis is not great in inherited conditions. Prognosis in hypomelanosis associated with underlying malignancy differs with the time of diagnosis, as most of them are mistaken for benign conditions like P.alba, IGH resulting in delayed treatment.

Complications

1. Malignancy - Most of the hypopigmented macules lack melanin in the affected area, thereby more prone to the harmful effects of UV radiation on keratinocytes and melanocytes. This renders them more susceptible to skin cancers than the general population. Patients are advised to minimize sun exposure and use sunscreen.

2. Systemic Disorder - Diagnosing the underlying root cause is important to treat the disease condition promptly and to improve the overall health rather than just treating hypomelanosis. For example, the presence of ash leaf spots indicates the possibility of neurocutaneous disorder (tuberous sclerosis).

3. Psychological Impact - This includes anxiety, stress, or depression that could affect an individual with hypopigmented skin lesions.

Consultations

The patient should be advised to consult a dermatologist if repigmentation is not achieved with effective treatment, or any suspicion arises of neurocutaneous disorder (tuberous sclerosis), HMF, the tumor of follicular infundibulum, or in any doubtful diagnosis. Interprofessional team consultation yields a better prognosis in patients affected by hypomelanosis in conjunction with systemic conditions.

Deterrence and Patient Education

- Most often, patients seek treatment owing to the psychological stress that accompanies the cosmetic appearance of skin lesions. They should be warned about the adverse effects of therapeutic medication such as skin atrophy, the formation of striae, telangiectasis. The use of psoralen in PUVA may be associated with hepatotoxicity. Females in the adolescent age group should be warned about the adverse effects of medication on pregnancy.

- Many of the patients could get a relapse of skin lesions after successful initial treatment. Educating the patients about underlying causes helps reduce the relapse.

- Patients are advised to monitor and report to the physician if any systemic symptoms occur, along with the skin lesions.

Pearls and Other Issues

Definitions of Macroscopic Terms

- Macule - Flattened skin lesion less than 5mm in size, distinguished by discoloration compared to surrounding normal skin

- Patch - Macular skin lesion with more than 5mm in size

- Lichenification - Thickened and rough skin with prominent skin markings, often due to repeated rubbing

Definitions of Microscopic Terms

- Hyperkeratosis - Thickened Stratum corneum, often associated with qualitative keratin abnormality

- Parakeratosis - Keratinization with retained nuclei of Stratum corneum; keratinization on mucous membranes is considered normal

- Spongiosis - Intercellular edema of the epidermis

- Acanthosis - An overgrowth of stratum spinosum

- Hydropic swelling - Intracellular edema of keratinocytes, often seen in viral infections

- Exocytosis - Infiltration of the epidermis by inflammatory cells

- Lentiginous - A linear pattern of melanocyte proliferation within the epidermal basal cell layer

- Epidermotropism - Migration of lymphocytes into epidermis without accompanying spongiosis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hypopigmented macules are the most common presentation of skin lesions. Often, the skin lesions are benign, and successful repigmentation can be achieved with prompt treatment. The lesions, in some cases, affect patients’ psychological and social well being. Therefore, it is important to continue medical education about hypopigmented skin lesions among healthcare professionals to improve the quality of care for their patients. Things to note-

- Follow the right approach to diagnosis (complete history and physical examination).

- Interspeciality communication for achieving better outcomes.

- Always evaluate for non-cutaneous signs and symptoms along with cutaneous findings to rule out underlying systemic disorders.

- Empathize and address psychological problems like depression, stress, and anxiety.

- Reassure patients about the benign nature of lesions and possible repigmentation.

- Re-evaluate, if the lesions are progressive and are not improving with treatment and rule out any underlying systemic disorders or associated malignancy.

- Educate patients about the course of treatment (how long they should be on medication, chances of repigmentation, benefits, and adverse effects of medications, phototherapy).

- Advise patients to avoid direct sun exposure, and use sunscreen for better outcomes of the treatment.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Poon S,Beach RA, Localised hypopigmentation: clarification of a diagnostic conundrum. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2018 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 30166398]

Carney BC,McKesey JP,Rosenthal DS,Shupp JW, Treatment Strategies for Hypopigmentation in the Context of Burn Hypertrophic Scars. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2018 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 29464168]

Vachiramon V,Thadanipon K, Postinflammatory hypopigmentation. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2011 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 21671990]

Hill JP,Batchelor JM, An approach to hypopigmentation. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2017 Jan 12; [PubMed PMID: 28082370]

Jindal R,Jain A,Gupta A,Shirazi N, Ash-leaf spots or naevus depigmentosus: a diagnostic challenge. BMJ case reports. 2013 Jun 10; [PubMed PMID: 23761491]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKarray M,McKinney WP, Tinea (Pityriasis) Versicolor 2020 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 29494106]

Kim SK,Kim EH,Kang HY,Lee ES,Sohn S,Kim YC, Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. International journal of dermatology. 2010 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 20465639]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrown F,Crane JS, Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis 2020 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 29489254]

Brown AE,Qiu CC,Drozd B,Sklover LR,Vickers CM,Hsu S, The color of skin: white diseases of the skin, nails, and mucosa. Clinics in dermatology. 2019 Sep - Oct; [PubMed PMID: 31896410]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTham HL,Linder KE,Olivry T, Autoimmune diseases affecting skin melanocytes in dogs, cats and horses: vitiligo and the uveodermatological syndrome: a comprehensive review. BMC veterinary research. 2019 Jul 19; [PubMed PMID: 31324191]

Haddad N,Oliveira Filho Jd,Reis MJ,Michalany AO,Nasser Kda R,Corbett AM, Tumor of follicular infundibulum with unique features. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2014 Nov-Dec [PubMed PMID: 25387502]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlikhan A,Felsten LM,Daly M,Petronic-Rosic V, Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview Part I. Introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 21839315]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSaleem MD,Oussedik E,Picardo M,Schoch JJ, Acquired disorders with hypopigmentation: A clinical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 May; [PubMed PMID: 30236514]

Al Aboud DM,Gossman W, Woods Light (Woods Lamp) 2020 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 30725878]

Al-Refu K, Dermoscopy is a new diagnostic tool in diagnosis of common hypopigmented macular disease: A descriptive study. Dermatology reports. 2019 Jan 23; [PubMed PMID: 31119026]

Shalaby MF,El-Din AN,El-Hamd MA, Isolation, Identification, and In Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Dermatophytes from Clinical Samples at Sohag University Hospital in Egypt. Electronic physician. 2016 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 27504173]

Veitch D,Miller J,Raichura S,McKenna J, Skin biopsy. British journal of hospital medicine (London, England : 2005). 2018 May 2; [PubMed PMID: 29727224]

AlGhamdi K,Kumar A,Moussa N, The role of vitamin D in melanogenesis with an emphasis on vitiligo. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2013 Nov-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 24177606]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBae JM,Jung HM,Hong BY,Lee JH,Choi WJ,Lee JH,Kim GM, Phototherapy for Vitiligo: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA dermatology. 2017 Jul 1; [PubMed PMID: 28355423]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLiu RC,Consuegra G,Chou S,Fernandez Peñas P, Vitiligo-like depigmentation in oncology patients treated with immunotherapies for nonmelanoma metastatic cancers. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2019 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 30618056]

Abdolkarimi B,Sepaskhah M,Mokhtari M,Aslani FS,Karimi M, Hypo-pigmented mycosis fungoides is a rare malignancy in pediatrics. Dermatology online journal. 2018 Nov 15; [PubMed PMID: 30695982]