Introduction

The cerebral venous system is a network most commonly described as two essential systems working in conjunction with one another: the superficial system and the deep system. The superficial cerebral system, which is typically more relevant in clinical scenarios, is made up of the sagittal sinuses and cortical veins, which drain the superficial surfaces of the cerebral hemispheres. The deep cerebral system is comprised of the straight, lateral, and sigmoid sinuses and functions to drain the deeper surfaces of the cerebral hemispheres.

Significant differentiation between the cerebral venous system and the rest of the body is the cerebral venous system contains both no valves or muscular layer, making it susceptible to ruptures and, ultimately, subdural hematomas. Both the superficial and deep venous systems eventually drain into the internal jugular veins, and ultimately the brachiocephalic vein followed by the right atrium via the superior vena cava.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The Superficial Cerebral Venous System

The superficial system starts with subcortical veins that drain the outer surfaces of the cortex, which drain into the pial veins sitting on the surface of the cortex. These pial veins then drain into the cerebral veins, which lie on the surface of the brain. There are many cerebral veins, but the largest three cerebral veins are the superficial middle cerebral veins that lie over the lateral sulcus, the vein of Trolard which connects the superior sagittal sinus to the middle cerebral vein, and the vein of Labbe which connects the middle cerebral vein to the lateral sinus.[1]

The superficial cerebral veins can be divided into three collecting systems: a mediodorsal group draining into the superior sagittal sinus (SSS) and the straight sinus (SS), a lateroventral group draining into the lateral sinus, and finally, an anterior group draining into the cavernous sinus. These veins connect by the great anastomotic vein of Trolard, which connects the SSS to the middle cerebral veins. The vein of Labbe connects the SSS and middle cerebral veins to the lateral sinus (LS).

The veins of the posterior fossa divide into three groups. The superior group drains into the Galenic system; the anterior group drains into the petrosal sinus, and the posterior group drains into the torcular Herophili and neighboring transverse sinuses. The cavernous sinus drains blood from the orbits, the inferior parts of the frontal and parietal lobes, and the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses. The union of the inferior sagittal sinus and the great vein of Galen forms the SS.[2]

Deep Cerebral Venous System

Internal cerebral veins and the basal veins of Rosenthal drain blood from the deep white matter of the cerebral hemisphere and the basal ganglia. These two venous groups then link to form the great vein of Galen, which drains into the straight sinus.[3]

Function

These two venous systems function to drain deoxygenated blood with carbon dioxide and metabolic waste away from the brain, allowing oxygenated blood to take its place. They drain the brain, eyes, meninges, and part of the face through the pterygoid plexus. Additionally, the dural venous sinuses drain the cerebrospinal fluid through arachnoid granulations and allow cerebrospinal fluid to return to the bloodstream.[4] Unlike other veins in the body, the cerebral veins have no muscular walls or valves. An exception is the large pial veins, which consist of a circumferential smooth muscle layer.

Embryology

The cerebral venous system begins its development as primary meninx, which is undifferentiated mesenchyme, which gives rise to a convergence of several vessels hypothetically originate from the mesoderm and neural crest cells. The initial salient vessels that develop are the pro-otic and anterior cerebral veins, as well as, the vena capitis lateralis and medialis.

On the rostral end, the supra-optic anastomosis and the posterior rhombencephalic veins originate. The anterior cerebral vein gives rise to the transverse sinuses. The cavernous sinus develops from the vena capitis medialis and the pro-otic vein. The vena capitis lateralis is unique in that it regresses, while the sigmoid sinuses form by the supra-optic anastomosis and the posterior rhombencephalic vein. The internal jugular veins derive from anterior cardinal veins.

Physiologic Variants

The most common physiological variant in the cerebral venous system and that one study found to be present in up to 21% of the population is a left-sided hypoplastic transverse sinus. The same research also found variation in the following parameters for the superficial middle cerebral vein, the vein of Trolard, and vein of Labbe; degree of development, connection, and dominance.[5]

Surgical Considerations

The cerebral venous veins are typically less surgically relevant than their arterial counterparts. Although there are some rare medical emergencies, one of which is cavernous sinus syndrome, which involves the cerebral veins and at times, surgical intervention may be necessary. The cavernous sinus is a difficult cavity to approach, and numerous surgical routes merit consideration when deciding how to enter the cavity. The routes of access available for consideration are comprised of two general approaches, the extradural and intradural routes.

Extradural Routes

The three extradural routes are the anterolateral, medial, and inferior. The anterolateral extradural approach is used to enter the floor of the cavity to approach the optic canal. The medial extradural approach is used to approach the contralateral side of the sinus and the pineal gland. The inferior extradural approach accesses the internal carotid artery within the sinus.

Intradural Routes

Among the intradural approach, there are two different routes to gain access; the superior and the lateral. The superior approach has a strategic vantage point of the anterior portion of the internal carotid artery. The lateral approach can examine a majority of the internal carotid artery within the sinus.[6][7]

Clinical Significance

Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

Cerebral venous thrombosis is a relatively rare disorder that can have dramatic consequences, including mortality. It occurs when a thrombosis of either the dural sinuses or cerebral veins materialize. A cerebral venous thrombosis typically presents in a myriad of conditions but can be fatal if missed. Therefore it is of utmost importance for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for any patient that presents with a subarachnoid hemorrhage, benign intracranial hypertension, severe headache, focal neurological deficit, seizures, or meningoencephalitis.

The risk factors for cerebral venous thrombosis, are typically those that create a prothrombic state. Risk factors include, but are not limited to, cancer, pregnancy, a post-partum state, and thrombophilia. One study found that 34% of patients who had a CVT had comorbidity of one of the following thrombophilia conditions; Protein C/S deficiency, Factor V Leiden, antithrombin deficiency, prothrombin mutation 20210, and hyperhomocysteinemia. In addition to genetic mutations, clinicians should suspect a cerebral venous thrombosis in any patient with head trauma, or post neurological surgery procedures, including jugular vein catheterization. Preferred modalities for imaging include non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan, CT venography, magnetic resonance imaging, or magnetic resonance venography.[8]

Cavernous Sinus Syndrome

Cavernous sinus syndrome presents when there is a compromise of the venous plexus that lies between the dural layers and the periosteal part of the skull, typically due to compression of the cranial nerves. It usually presents with proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, conjunctival congestion, horner's syndrome, and trigeminal sensory loss. The structures involved in cavernous sinus syndrome include the abducens nerve, the internal carotid artery, and the sympathetic plexus. There is often a delay in diagnosis, making it imperative that physicians retain a high index of suspicion for any patient who presents with the mentioned constellation of symptoms.[9][10]

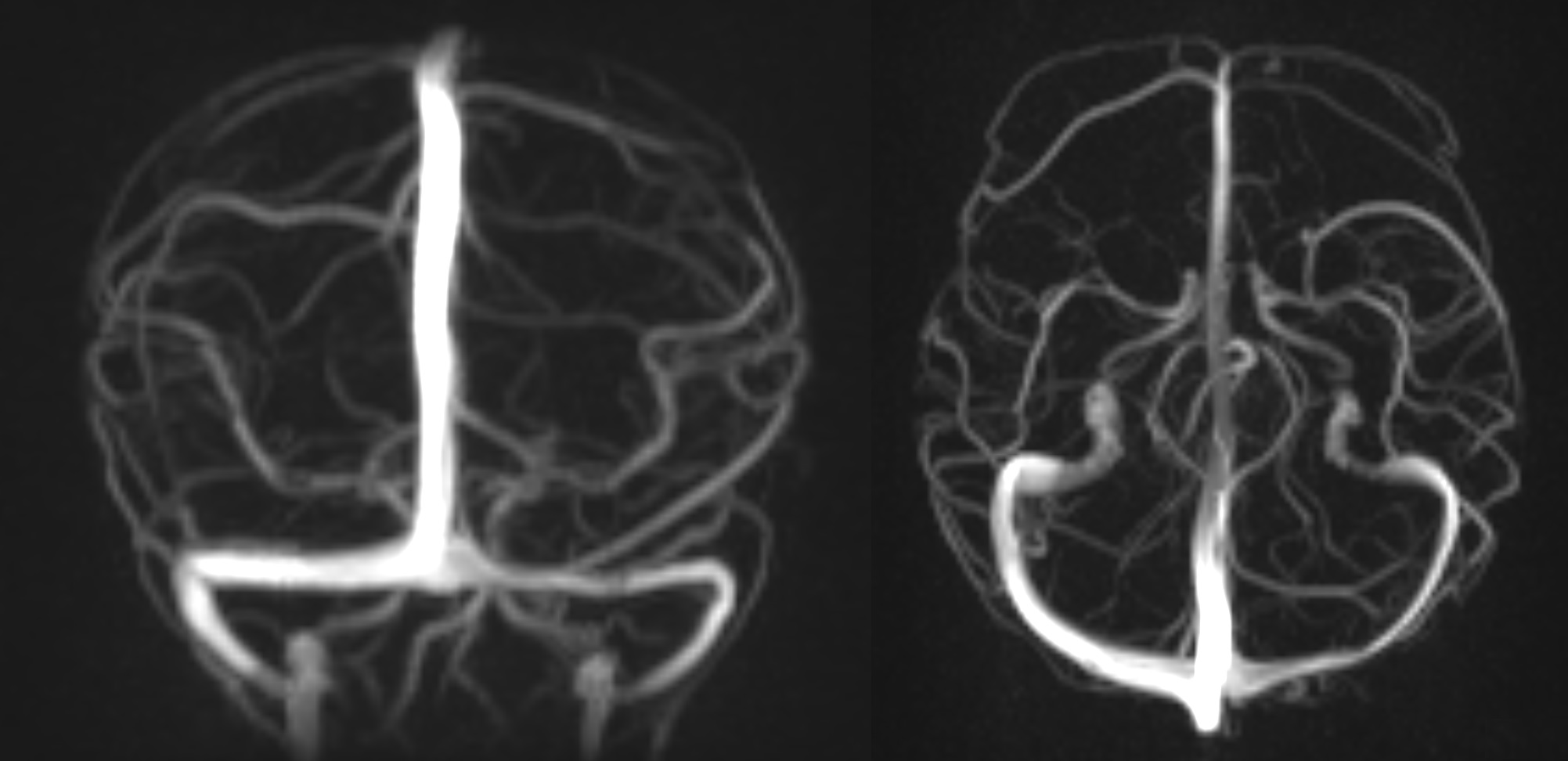

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Letchuman V, Donohoe C. Neuroanatomy, Superior Sagittal Sinus. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536222]

Kournoutas I, Rodriguez Rubio R. Venous anatomy of the infratentorial compartment. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2020:169():73-86. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804280-9.00004-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32553299]

Tabani H, Tayebi Meybodi A, Benet A. Venous anatomy of the supratentorial compartment. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2020:169():55-71. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804280-9.00003-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32553298]

Hufnagle JJ, Tadi P. Neuroanatomy, Brain Veins. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536212]

Fujii S, Kanasaki Y, Matsusue E, Kakite S, Kminou T, Ogawa T. Demonstration of cerebral venous variations in the region of the third ventricle on phase-sensitive imaging. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2010 Jan:31(1):55-9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1752. Epub 2009 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 19729543]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMasuoka J, Matsushima T, Hikita T, Inoue E. Cerebellar swelling after sacrifice of the superior petrosal vein during microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2009 Oct:16(10):1342-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.12.024. Epub 2009 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 19576780]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDavidson L, McComb JG. The safety of the intraoperative sacrifice of the deep cerebral veins. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2013 Feb:29(2):199-207. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1958-7. Epub 2012 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 23180313]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTadi P, Behgam B, Baruffi S. Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083599]

Mehta MM, Garg RK, Rizvi I, Verma R, Goel MM, Malhotra HS, Malhotra KP, Kumar N, Uniyal R, Pandey S, Sharma PK. The Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsies: A Prospective Observational Study. Neurology India. 2020 May-Jun:68(3):630-635. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.289003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32643676]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIwanaga J, Anand MK, Camacho A, Rodriguez F, Watson C, Caskey EL, Dumont AS, Tubbs RS. Surgical anatomy of the internal carotid plexus branches to the abducens nerve in the cavernous sinus. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2020 Apr:191():105690. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105690. Epub 2020 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 31982693]