Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Distal Tibiofibular Joint (Tibiofibular Syndesmosis)

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Distal Tibiofibular Joint (Tibiofibular Syndesmosis)

Introduction

A syndesmosis is a fibrous joint characterized by two adjacent bones connected by ligamentous structures, including a strong interosseous membrane (IOM). [1] The distal tibiofibular syndesmosis, which is comprised of two bones, the distal tibia and distal fibula, and four stabilizing ligaments, the anterior-inferior and posterior-inferior tibiofibular ligaments (AITFL and PITFL), the inferior transverse ligament (ITL), and the interosseous ligament (IOL), a distal continuation of the interosseus membrane. The syndesmosis is responsible for the integrity of ankle mortise. The syndesmosis is susceptible to compromise during high ankle sprains, ligament tears, and ankle fractures. This article will highlight the anatomical structure and function of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis as well as its clinical and surgical significance.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The syndesmotic articulation of the distal tibiofibular joint occurs between the convex surface of the distal tip of the fibula and the concave fibular notch of the distal tibia. The stability of the syndesmosis is crucial to proper dynamic ankle and lower extremity function. The osseous portion of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis consists of the tibia and fibula, and the four connecting ligaments include the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, inferior transverse ligament, and the interosseus ligament.[2] The primary function of the distal ligaments of the tibiofibular syndesmosis is to prevent the fibula from displacing (laterally, and/or anteriorly/posteriorly) from its groove in the tibia.[3] The ankle syndesmosis resists pathologic external rotational forces that attempt to laterally/externally rotate the talus, thereby displacing and pushing the fibula away from the tibia.

The anterior-inferior tibiofibular ligament originates from the longitudinal tubercle on the anterior surface of the lateral malleolus and attaches on the anterolateral tubercle of the tibia (Chaput fragment). It functions to hold the tibia and fibula tightly together and prevents excessive fibular displacement and external talar rotation. The posterior-inferior tibiofibular ligament originates at the posterior tibial tubercle (Volkmann fragment) and attaches to the posterior lateral malleolus. It functions alongside the anterior-inferior tibiofibular ligament to hold the tibia and fibula together. Slightly deep to the posterior-inferior tibiofibular ligament is the inferior transverse ligament, which serves to create a labrum that deepens the articular surface of the tibia posteriorly, helping to increase joint stability. The interosseus ligament lies at the distal end of the interosseous membrane and acts as a spring to prevent excessive separation of the tibiofibular mortise during ankle dorsiflexion and heel strike.

Embryology

The limb buds of the embryo typically begin forming around 4 to 5 weeks after fertilization, as activation of mesenchymal cells of the lateral plate mesoderm cause a limb bud to start growing. The limb bud formation depends on many factors, which include the apical ectodermal ridge (AER), HOX genes, retinoic acid, sonic hedgehog (SHH) genes, and the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA). The AER forms via a thickening of the distal ectodermic border and produces signals that initiate rapid undifferentiated growth of the mesenchyme of the underlying progress zone, beginning limb formation. Retinoic acid acts to initiate transcription factor production and growth of the limbs by upregulating HOX genes and SHH genes, which then leads to synchronized limb outgrowth along the anteroposterior, dorsoventral, and proximo-distal axes of growth. Additionally, the T-box transcription factor Tbx4 is expressed in the development of the lower limbs and produces a growth factor, Fgf10, which acts at the AER to stimulate mitosis and further limb growth. The ZPA is a collection of cells that lie close to the AER on the posterior aspect of the limb and moves distally with the AER as the limb grows. The ZPA releases retinoic acid as well, which controls the development and growth of the limb along the anteroposterior axis. SHH and Fgf products promote HOX gene expression, leading to more complex limb polarization and regional formation of the developing limb. Errors in HOX gene expression, as well as T-box gene expression, can lead to malformations of limbs or changes in limb morphology.[3][4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the distal leg includes the anterior and posterior tibial arteries, both branches of the popliteal artery originating from the femoral artery and external iliac artery proximally. The blood supply to the syndesmotic region itself, however, has not been extensively studied. The studies published on the topic have described anatomical variations in the vasculature supplying blood to the anterior aspect of the tibiofibular syndesmosis. Different variants of blood supply to the anterior syndesmosis seen in the literature include[5][6]:

- Branches stemming primarily from the perforating branch of the peroneal artery

- Branches from the peroneal artery, supplemented by smaller vessels from the tibial artery

- Supply from the tibial artery predominantly with smaller branches from the peroneal artery

Blood supply to the posterior aspect of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis has less variation. In most cases, the blood supply to the posterior ligaments of the syndesmosis is supplied solely by the peroneal artery. In rarer instances, branches from the tibial artery also supplemented the vascular supply to the area.[5]

Lymphatic vessels of the lower extremity divide into superficial and deep vessels, which further subdivide into medial and lateral groups. These vessels drain into the popliteal, deep or superficial inguinal, external iliac, or lumbar (aortic) nodes.[4]

Nerves

The nerves in the area of the tibiofibular syndesmosis include the deep peroneal (fibular) nerve, tibial nerve, and sural nerve.[7][8] The peroneal nerve is a sciatic nerve branch that begins where the sciatic nerve splits into the common tibial and common peroneal nerves, usually at the level of the lower thigh.[9][10] The peroneal nerve further splits into a superficial branch that innervates muscles in the lateral compartment of the leg, and the deep branch that innervates muscles in the anterior compartment of the leg and the dorsum of the foot. The tibial nerve runs posterior to the tibia and supplies the deep muscles in the posterior leg.[4]

Physiologic Variants

Variation in the physiology of the tibiofibular syndesmosis is uncommon. However, two studies conducted recently explored anatomic variations concerning growth as well as CT characterization of anatomic morphology and structural differences in the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis.

Liu et al. described inconsistencies in reduction outcomes of the tibiofibular syndesmosis due to anatomical differences in morphology of the fibular incisura of the tibia. Variation in morphology was confirmed by CT imaging, and the authors described five morphologic variations of the fibular incisura: crescentic, trapezoid, widow’s peak, flat, and chevron. Careful evaluation and measurements taken via CT imaging to account for these anatomical differences are integral in preventing malreduction of the syndesmosis.[11] Additionally, Nault et al. reported on changes in the anatomy of the syndesmosis during growth in the pediatric and adolescent population. During growth, the fibula shifts slightly laterally as measured by the distance between the tibia and the fibula at the middle of the fibular incisura, and external rotation of the fibula decreases as the skeleton of children matures.[12] These physiologic variants are important to consider for surgeons when repairing syndesmotic injuries.

Surgical Considerations

Injuries to the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis constitute about 5 to 10% of ankle sprains and 11 to 20% of ankle fractures. In cases of confirmed syndesmotic instability either during intra-operative fixation of an associated ankle fracture or a separate isolated syndesmotic injury, operative treatment is indicated.[13]

Screw versus tightrope fixation methods

Regardless of the surgical technique utilized, the goal of syndesmotic repair/fixation is to achieve an anatomic reduction of the syndesmosis. Studies have previously demonstrated anatomic reduction is crucial to successful outcomes in patients.[14] A 2018 meta-analysis comparing suture button (i.e., tightrope) fixation versus screw fixation for syndesmosis injuries reported the former technique resulted in improved functional outcomes as well as lower rates of broken implant and joint malreduction compared to the screw fixation patients.[15] Nonetheless, similar rates of postoperative complications were seen otherwise when comparing the two treatment groups. Other studies have also reported syndesmotic malreduction utilizing screw fixation syndesmotic repair techniques can occur in up to 52% of cases, leading to poor functional outcomes.[1][11] Typically, two 3.5 mm or 4.5 mm syndesmotic screws placed 2 to 5 cm above the joint line is the preferred method of fixation, but there are no reports of a significant improvement in outcomes for using one versus two screws or specific screw sizes.

Incorporating intra-operative three-dimensional imaging has been suggested as a potential option for improving tibiofibular reduction outcomes. Imaging may also be used pre-operatively to determine any anatomical differences in the anatomic morphology of the fibular incisura on the tibia to decrease instances of malreduction.[13][16]

Clinical Significance

The tibiofibular syndesmosis is very important in ankle stability and transmission of load during gait and other activity. Thus, patients with syndesmotic injury frequently present with ankle instability and difficulty bearing weight, in addition to anterolateral ankle pain.[13][17]

Two tests are commonly used to assess the syndesmosis on physical exam, including the external rotation test and the squeeze test. The external rotation test involves the patient sitting with the knee flexed to 90 degrees while the foot is gently grasped and rotated laterally with the ankle locked in neutral. This test helps demonstrate the integrity of the syndesmotic ligaments. The squeeze test is performed by placing a thumb on the tibia and fingers on the fibula at the midpoint of the lower leg and subsequently squeezing the tibia and fibula together. This test helps identify a fracture or if the test elicits pain, indicating a positive test.[18]

The most common mechanism for tibiofibular syndesmotic injury is external rotation of the talus, which causes the fibula to separate excessively from the tibia, followed by hyperdorsiflexion of the foot.[13][1] Syndesmotic injury occurs in a large percentage of physical or sports-related ankle injuries and is sometimes difficult to diagnose, leading to many poor functional outcomes in patients. Injuries to the syndesmosis are associated with a longer period of recovery and discomfort; this is likely due to the fact that the perforating peroneal artery (the primary vascular supply to the anterior syndesmosis) is vulnerable to injury in association with syndesmotic injury, and injury to this vessel would compromise sufficient blood flow to the injured syndesmosis, resulting in lengthy recovery.[17]

The primary goals in managing syndesmotic injury are to restore proper fibular length and ensure a proper position in regards to rotation and proximity of the fibula to the tibia.[18] Non-operative treatment strategies for syndesmotic injury have been described with overall positive results, and are typically indicated for an isolated syndesmotic sprain with no diastasis or severe ankle instability. Treatment might include a CAM boot or cast with limited weight-bearing for 2 to 3 weeks, followed by a gradual increase in weight-bearing activity until pain is absent. Ultimately, there is minimal consensus on the proper mode of treatment for syndesmotic injury pre-operatively, intra-operatively, or post-operatively, and outcomes are largely dependent on careful clinical evaluation and management strategy on an individual basis.[1]

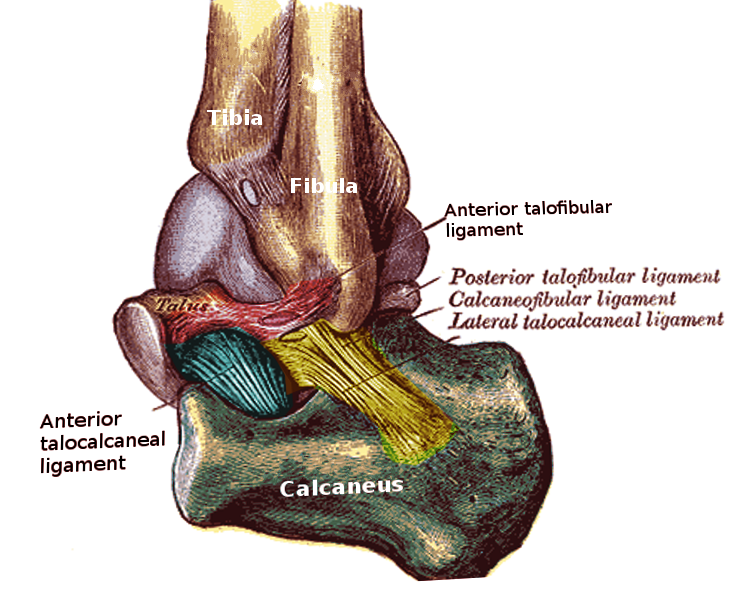

Media

References

Yuen CP, Lui TH. Distal Tibiofibular Syndesmosis: Anatomy, Biomechanics, Injury and Management. The open orthopaedics journal. 2017:11():670-677. doi: 10.2174/1874325001711010670. Epub 2017 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 29081864]

Hermans JJ, Beumer A, de Jong TA, Kleinrensink GJ. Anatomy of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis in adults: a pictorial essay with a multimodality approach. Journal of anatomy. 2010 Dec:217(6):633-45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01302.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21108526]

Barham G, Clarke NM. Genetic regulation of embryological limb development with relation to congenital limb deformity in humans. Journal of children's orthopaedics. 2008 Feb:2(1):1-9. doi: 10.1007/s11832-008-0076-2. Epub 2008 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 19308596]

Lezak B, Summers S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Extensor Hallucis Longus Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969697]

McKeon KE, Wright RW, Johnson JE, McCormick JJ, Klein SE. Vascular anatomy of the tibiofibular syndesmosis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2012 May 16:94(10):931-8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00604. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22617922]

Hyland S, Sinkler MA, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Popliteal Region. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422486]

Khan IA, Mahabadi N, D’Abarno A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Leg Lateral Compartment. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137811]

Binstead JT, Munjal A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Calf. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083629]

Miniato MA, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Back, Lumbosacral Trunk. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969700]

Hicks BL, Lam JC, Varacallo M. Piriformis Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846222]

Liu GT, Ryan E, Gustafson E, VanPelt MD, Raspovic KM, Lalli T, Wukich DK, Xi Y, Chhabra A. Three-Dimensional Computed Tomographic Characterization of Normal Anatomic Morphology and Variations of the Distal Tibiofibular Syndesmosis. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2018 Nov-Dec:57(6):1130-1136. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2018.05.013. Epub 2018 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 30197255]

Nault ML, Hébert-Davies J, Yen YM, Shore B, Jarrett DY, Kramer DE. Variation of Syndesmosis Anatomy With Growth. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2016 Jun:36(4):e41-4. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000566. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26090974]

Fort NM, Aiyer AA, Kaplan JR, Smyth NA, Kadakia AR. Management of acute injuries of the tibiofibular syndesmosis. European journal of orthopaedic surgery & traumatology : orthopedie traumatologie. 2017 May:27(4):449-459. doi: 10.1007/s00590-017-1956-2. Epub 2017 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 28391516]

Park YH, Ahn JH, Choi GW, Kim HJ. Comparison of Clamp Reduction and Manual Reduction of Syndesmosis in Rotational Ankle Fractures: A Prospective Randomized Trial. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2018 Jan-Feb:57(1):19-22. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.05.040. Epub 2017 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 29037926]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShimozono Y, Hurley ET, Myerson CL, Murawski CD, Kennedy JG. Suture Button Versus Syndesmotic Screw for Syndesmosis Injuries: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. The American journal of sports medicine. 2019 Sep:47(11):2764-2771. doi: 10.1177/0363546518804804. Epub 2018 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 30475639]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFranke J, von Recum J, Suda AJ, Grützner PA, Wendl K. Intraoperative three-dimensional imaging in the treatment of acute unstable syndesmotic injuries. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2012 Aug 1:94(15):1386-90 [PubMed PMID: 22854991]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNorkus SA, Floyd RT. The anatomy and mechanisms of syndesmotic ankle sprains. Journal of athletic training. 2001 Jan-Mar:36(1):68-73 [PubMed PMID: 16404437]

Zalavras C, Thordarson D. Ankle syndesmotic injury. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2007 Jun:15(6):330-9 [PubMed PMID: 17548882]