Introduction

Cryptococcosis is an important opportunistic infection that causes more than 100,000 HIV-related deaths each year. It was named the Busse-Buschke disease because of its first description by Otto Busse and Abraham Buschke in 1894.[1]

Even though the infection is usually HIV-related, in many centers (especially in developed countries), most of the non-HIV-related cases include patients under immunosuppressive treatments or with organic failure syndromes, transplants, innate immunological problems, common variable immunodeficiency syndrome, and hematological disorders.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There are more than 50 species of Cryptococcus; C. neoformans and C. gattii cause the majority of infections, and some consider them the only pathogens in humans.

C. neoformans is an encapsulated yeast that can be found in aged pigeon droppings which causes mild infections, from airway colonization or asymptomatic ones in laboratory workers to severe infections like meningitis or disseminated disease. It is the most common species from the Cryptococcus genre in our region (Brazil) and other temperate weathers around the world. [3]

The major predisposing factor to cryptococcal infection is HIV; however, the predisposing factors in non-HIV patients are as follows[4]:

Syndromes and Autoantibodies

- Idiopathic CD4 lymphopenia

- Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis with autoantibodies to granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor

- Autoantibodies to interferon-gamma

Monogenic Disorders

- Primary immunodeficiency owing to GATA2 mutations.

- Chronic granulomatous disease

- Hyperimmunoglobulin E recurrent infection syndrome (Job syndrome)

- X-linked CD40L deficiency (hyper-IgM syndrome)

Polygenetic modifiers

- Fc gamma receptor (FCGR) II polymorphism

Comorbidities

- Sarcoidosis, autoimmune disease, steroid treatment

- Hepatic disease

- Solid organ transplant conditioning

Epidemiology

Approximately 1 million cases of cryptococcal meningitis are reported annually. The incidence have markedly increased since 1950s because of corticosteroid use and improvement of survival in cancer patients. However, most of the cryptococcal reports come from the 1980s and are predominantly AIDS-related cases. Approximately 6% of patients with AIDS develop cryptococcal infections, and patients with AIDS-associated cryptococcosis account for 85% of all patients diagnosed with cryptococcosis. [2][1]

Pathophysiology

The organism is acquired by inhalation. After being deposited into the pulmonary alveoli, the yeast spores must survive the normal to high pH and the physiological concentrations of carbon dioxide before they are phagocytized by alveolar macrophages, a more acidic environment, and disseminated after a latent period of containment in the lung lymph nodes. The essential factor in the survival of C. neoformans in this extracellular environment is glucosylceramide synthase. [5]

The host response includes both cellular and humoral components. Possibly, the eradication of Cryptococci relies on natural killer cells and antibody-dependent cell-mediated killing. [6]

While all organs can be involved, Cryptococcus spp. have a strong affinity for the central nervous system. This neurotropism is linked to several cryptococcal-specific factors which facilitate the permeability of the blood-brain barrier; between them, metalloproteinases and ureases enzymes cause neuromodulation and mechanisms facilitate survival in the nutrient-deprived environment of the brain (autophagy and high-affinity sugar transporters). [7][8]

There can be little or no necrosis or organ damage until later disease. In patients with heavy infections, organ dysfunction may be accelerated, primarily due to tissue distortion caused by the growing fungal burden. [9]

Histopathology

C. neoformans reproduces by budding and forms round yeast-like cells that are 3 to 6 micrometers in diameter. In the host and culture media, each cell is surrounded by a large polysaccharide capsule that has antiphagocytic properties and may be immunosuppressive. It can form smooth, convex, yellow, or tan colonies on solid media at 20 to 37 degrees C. The non-pathogenic strains do not grow at this temperature. [10]

History and Physical

Cryptococcal meningitis usually presents as a subacute meningoencephalitis. The patient commonly presents with neurological symptoms such as a headache, altered mental status, and other signs and symptoms include lethargy along with fever, stiff neck (both associated with an aggressive inflammatory response), nausea and vomiting. Some patients who are HIV positive may have minimal or nonspecific symptoms at presentation.

The duration of symptoms from onset to a presentation is usually 1 to 2 weeks in HIV cases and 6 to 12 weeks in non-HIV cases.

Visual symptoms include diplopia and photophobia at the onset, and reduced acuity later in the disease (due to high cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure or compression of the optic nerve and tracts). Other findings include hearing defects, ataxia, aphasia, seizures, and chorea.

Although C. neoformans enters the body through the lungs, the central nervous system (CNS) is the main site of evident clinical infection. [4]

Evaluation

The workup at initial evaluation should depend on CSF lab tests. However, to prevent a post-dural puncture cerebral herniation, a CT scan or MRI of the brain or a fundus examination should be considered before performing a lumbar puncture. [4]

Blood and CSF should be cultured for fungi and tested for cryptococcal antigen. Routine lab tests may be normal even with widespread disease. Opening pressure has to be measured at the first spinal tap, a pressure over 25 cm of water is a predictor of a poor prognosis. [4]

CSF usually presents low glucose and high protein levels. White cell count can be normal or higher than 20 microL and have a lymphocyte predominance. Nevertheless, CSF can be normal and have positive results on India ink stain and antigen testing (especially in HIV-positive patients who do not have an adequate inflammatory response). [11]

Treatment / Management

Treatment has not varied for a decade, according to recommendations from the 2010 IDSA (Infectious Diseases Society of America) update. The first-line antifungal treatment is based on the induction, consolidation, and maintenance of the following three types of patients[12][9]:(A1)

HIV-Related Disease

- Induction therapy

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/day) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day orally) for 2 weeks (A1 Evidence)

- Liposomal amphotericin B (3 to 4 mg/kg/day) or amphotericin B lipid complex (5 mg/kg/day; kidney function surveillance) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks (B2 Evidence)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/day) or liposomal amphotericin B (3 to 4 mg/kg/day) or amphotericin B lipid complex (5 mg/kg/day, for patients who do not tolerate flucytosine) for 4 to 6 weeks (B2 Evidence)

- Induction therapy alternatives

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate + fluconazole (B1 Evidence)

- Fluconazole + flucytosine (B2 Evidence)

- Fluconazole (B2 Evidence)

- Itraconazole (C2 Evidence)

- Consolidation therapy

- Fluconazole (400 mg/day) for 8 weeks (A1 Evidence)

- Maintenance therapy

- Fluconazole (200 mg/day) for 1 or more years (A1 Evidence)

- Maintenance therapy alternatives

- Itraconazole (400 mg/day) for 1 or more years (C1 Evidence)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (1 mg/kg/week) for 1 or more years (C1 Evidence)

Transplant Related Disease

- Induction therapy

- Liposomal amphotericin B (3 to 4 mg/kg/day) or amphotericin B lipid complex (5 mg/kg/day) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks (B3 Evidence)

- Induction therapy alternatives

- Liposomal amphotericin B (6 mg/kg/day) or amphotericin B lipid complex (5 mg/kg/day) for 4 to 6 weeks (B3 Evidence)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 mg/kg/day) for 4 to 6 weeks (B3 Evidence)

- Consolidation therapy

- Fluconazole (400 to 800 mg/day) for 8 weeks (B3 Evidence)

- Maintenance therapy

- Fluconazole (200 to 400 mg/day) for 6 months to 1 year (B3 Evidence)

Not HIV/Transplant Related Disease

- Induction therapy

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/day) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for 4 or more weeks (B2 Evidence)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/day) for 6 weeks (B2 Evidence)

- Liposomal amphotericin B (3 to 4 mg/kg/day) or amphotericin B lipid complex (5 mg/kg/day) combined with flucytosine, 4 weeks (B3 Evidence)

- Amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7 mg/kg/day) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks (B2 Evidence)

- Consolidation therapy

- Fluconazole (400 to 800 mg/day) for 8 weeks (B3 Evidence)

- Maintenance therapy

- Fluconazole (200 mg/day) for 6 to 12 months (B3 Evidence)

The combination of amphotericin B and flucytosine has proved the most effective measure to clear the infection, and it showed a greater survival benefit over amphotericin alone. However, due to its cost, flucytosine is often unavailable in poor-resource settings where the disease burden is significant. Combinations of amphotericin B and fluconazole have been studied, and greater results have been found over amphotericin B alone. [13],[14],[15](A1)

Without treatment, the clinical course progresses to confusion, seizures, reduced level of consciousness, and coma.

Headache refractory to pain-killers can be treated with spinal decompression after an adequate neuroimaging evaluation with a CT scan or MRI. The safe maximum volume of CSF that can be drained at one lumbar puncture is unclear, but up to 30 mL are frequently removed with the pressure checked after each 10 mL removed. [4],[16]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis is based upon the following causes of intracranial mass lesions and infections[4]:

- Pyogenic, Nocardial or Aspergillus abscess

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Histoplasma capsulatum infection

- Acanthamoeba infection

- Neurosyphilis

- Lymphomas, lymphocytic meningitis, meningeal metastases

- Hemorrhages

Prognosis

The initial prognosis depends on mortality predictors such as the following[2],[4],[17],[18]:

- CSF opening pressure of more than 25 cm of water

- Low CSF white cells count

- Sensory impairment

- Delayed diagnosis

- Elevated CSF antigen titers

- Rate of infection clearance

- CSF yeast count more than 10 mm^3 (a common practice in Brazil)[19]

- Non-HIV-related patients and the prognostic factors in these patients, in addition to the already mentioned:

- Markers of a poor inflammatory response

- Absence of headache

- Underlying hematological malignancy

- Chronic renal or liver disease

Mortality varies from country to country depending on the resource settings. It remains high in the United States and France, with a 10-week mortality of 15% to 26%, and it is even higher in non-HIV patients because of the delayed diagnosis and dysfunctional immune responses. On the other hand, in poor-resource countries, mortality increase from 30% to 70% in 10 weeks because of the late presentation and lack of access to drugs, manometers, and optimal monitoring.[12]

Complications

Complications include the following[4]:

- Persistent Infection - Persistently positive results of cultures of CSF after 4 weeks of proven antifungal therapy at an established effective dose is a reasonable starting point.

- Relapsed Infection (based upon two main characteristics)

- The recovery of viable Cryptococci from a previously checked sterile body site is essential.

- Recrudescence of signs and symptoms at the previous site of disease supports the presence of disease.

- Elevated CSF Pressure - Acute elevated symptomatic CSF pressure (sometimes due to initial antifungal therapy) should be managed rapidly by decompression via repeated lumbar taps, transitory lumbar drainage catheter, or ventriculostomy in some patients.

- Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS):

- Unmasking IRIS, in which cryptococcal symptoms appear after the initiation of antiretroviral therapy.

- Paradoxical IRIS during the treatment of cryptococcosis and administration of antiretroviral therapy.

Cerebral cryptococcomas can cause significant short- and long-term neurological complications. They are hard to treat and normally require a long-term antifungal therapy.

Hydrocephalus is a later complication and can present as dementia or chronic headache.

Pearls and Other Issues

HIV-Infected Patients

- The incidence of cryptococcal meningitis has diminished in patients with antiretroviral therapy (ART).

- Symptoms typically begin insidiously during a 2-week period. The most common symptoms are fever, malaise, and headache. Cranial neuropathies may also be present. Symptoms like cough, dyspnea, and skin rash suggest a disseminated disease.

- The antifungal prophylaxis is not recommended as a routine for cryptococcal disease (II-B Evidence).

Non-HIV-Infected Patients

- C. neoformans disseminates hematogenously from the respiratory tract and has a propensity for the central nervous system. The inflammatory response in the brain is usually milder than the one in bacterial meningitis. The inflammatory infiltrate is comprised of mononuclear cells predominantly with occasional polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Generally, brain involvement is diffuse but localized infection can occur (cryptococcoma).

- Most individuals with cryptococcal meningitis are immunocompromised. The most common cases include glucocorticoid therapy, organ transplantation, cancer, and other conditions such as sarcoidosis and hepatic failure.

- Symptom presentation is variable. Some patients have symptoms for up to 2 to 8 months before diagnosis while others can present an acute illness in a few days. Approximately 50% of cases have fever. Generally, headache, lethargy, personality changes, and memory loss can appear over 2 to 4 weeks. Some patients can also present as a disseminated disease.

The definitive diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis is made by culture from the CSF. The opening pressure should be measured along with India ink evaluation, cryptococcal antigen testing, fungal culture, and routine spinal fluid studies. A positive cryptococcal antigen in the CSF or serum can strongly suggest the infection before the cultures become positive in high-risk patients.

Neuroimaging must be performed prior to lumbar puncture if there is a concern for a high intracranial pressure.

The principal antifungal agents for the treatment of cryptococcal meningitis are intravenous amphotericin B deoxycholate and its lipid formulations, oral flucytosine, and oral fluconazole. While amphotericin B and flucytosine are fungicidal, fluconazole is only fungistatic. Lipid formulations of amphotericin B are preferred on patients with renal dysfunction or at risk for renal failure.

Cryptococcal meningitis is fatal if untreated. The therapeutic regime includes three phases: Induction followed by consolidation for a total of 10 weeks (to rapidly sterilize the CSF and to decrease early mortality) and maintenance therapy to prevent relapses.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cryptococcal meningitis is a serious disorder with high mortality and thus best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a radiologist, emergency department physician, internist, infectious disease specialist, infectious disease nurse, neurologist and a pharmacist. Patients are usually treated with two antifungal agents and the treatment duration can be as long as 6-24 months.

Patients who are immunocompromised as well as those with neurological symptoms tend to have poor outcomes despite optimal treatment.

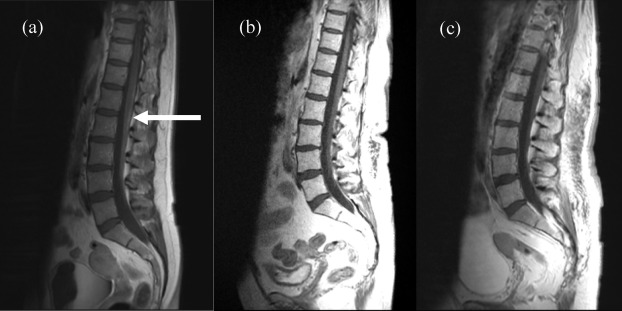

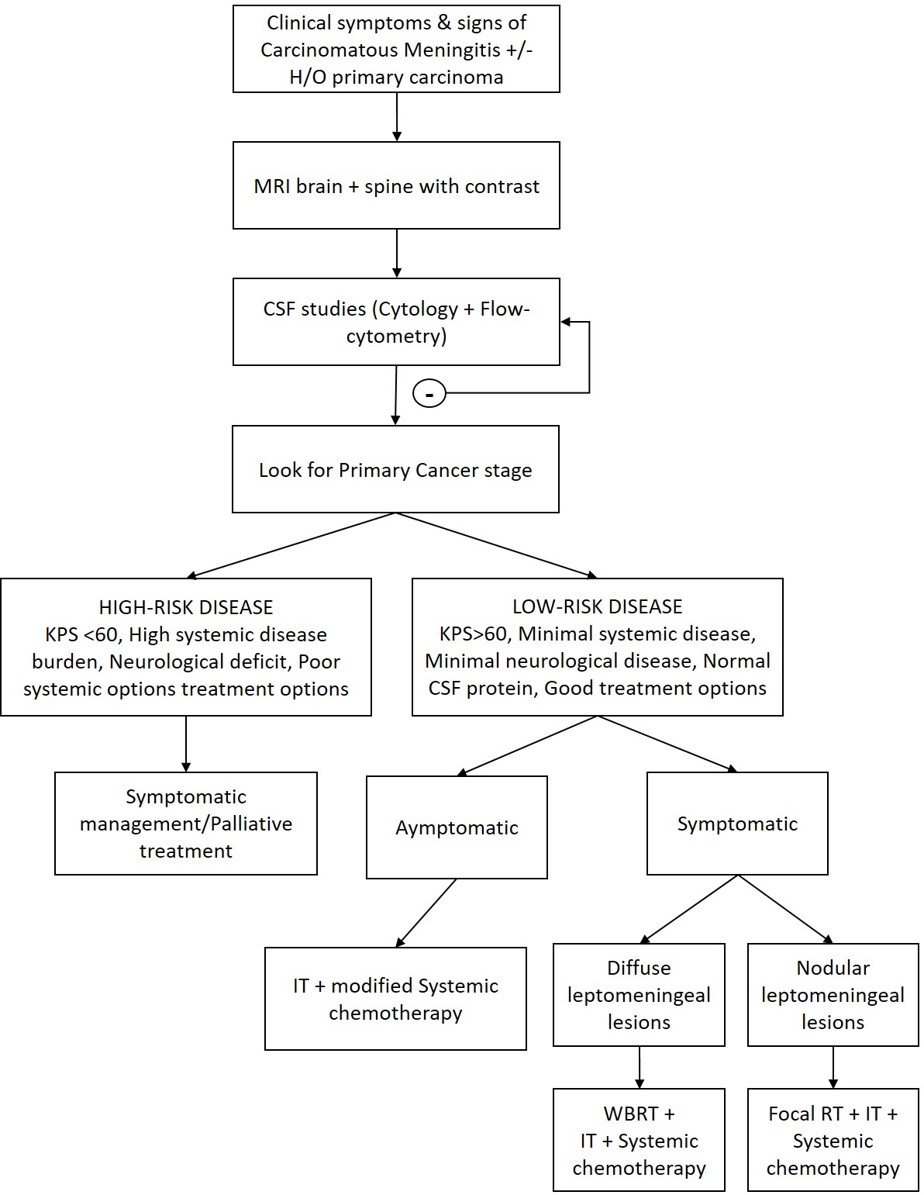

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

May RC, Stone NR, Wiesner DL, Bicanic T, Nielsen K. Cryptococcus: from environmental saprophyte to global pathogen. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2016 Feb:14(2):106-17. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.6. Epub 2015 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 26685750]

Pappas PG. Cryptococcal infections in non-HIV-infected patients. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 2013:124():61-79 [PubMed PMID: 23874010]

Takahara DT, Lazéra Mdos S, Wanke B, Trilles L, Dutra V, Paula DA, Nakazato L, Anzai MC, Leite Júnior DP, Paula CR, Hahn RC. First report on Cryptococcus neoformans in pigeon excreta from public and residential locations in the metropolitan area of Cuiabá, State of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo. 2013 Nov-Dec:55(6):371-6. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652013000600001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24213188]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilliamson PR, Jarvis JN, Panackal AA, Fisher MC, Molloy SF, Loyse A, Harrison TS. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis and therapy. Nature reviews. Neurology. 2017 Jan:13(1):13-24. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.167. Epub 2016 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 27886201]

Rittershaus PC, Kechichian TB, Allegood JC, Merrill AH Jr, Hennig M, Luberto C, Del Poeta M. Glucosylceramide synthase is an essential regulator of pathogenicity of Cryptococcus neoformans. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006 Jun:116(6):1651-9 [PubMed PMID: 16741577]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchmidt S, Zimmermann SY, Tramsen L, Koehl U, Lehrnbecher T. Natural killer cells and antifungal host response. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2013 Apr:20(4):452-8. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00606-12. Epub 2013 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 23365210]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVu K,Tham R,Uhrig JP,Thompson GR 3rd,Na Pombejra S,Jamklang M,Bautos JM,Gelli A, Invasion of the central nervous system by Cryptococcus neoformans requires a secreted fungal metalloprotease. mBio. 2014 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 24895304]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStie J, Fox D. Blood-brain barrier invasion by Cryptococcus neoformans is enhanced by functional interactions with plasmin. Microbiology (Reading, England). 2012 Jan:158(Pt 1):240-258. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.051524-0. Epub 2011 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 21998162]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePerfect JR, Bicanic T. Cryptococcosis diagnosis and treatment: What do we know now. Fungal genetics and biology : FG & B. 2015 May:78():49-54. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.10.003. Epub 2014 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 25312862]

Nyazika TK, Hagen F, Meis JF, Robertson VJ. Cryptococcus tetragattii as a major cause of cryptococcal meningitis among HIV-infected individuals in Harare, Zimbabwe. The Journal of infection. 2016 Jun:72(6):745-752. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.02.018. Epub 2016 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 27038502]

Abassi M,Boulware DR,Rhein J, Cryptococcal Meningitis: Diagnosis and Management Update. Current tropical medicine reports. 2015 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 26279970]

Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, Harrison TS, Larsen RA, Lortholary O, Nguyen MH, Pappas PG, Powderly WG, Singh N, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010 Feb 1:50(3):291-322. doi: 10.1086/649858. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20047480]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDay JN, Chau TTH, Wolbers M, Mai PP, Dung NT, Mai NH, Phu NH, Nghia HD, Phong ND, Thai CQ, Thai LH, Chuong LV, Sinh DX, Duong VA, Hoang TN, Diep PT, Campbell JI, Sieu TPM, Baker SG, Chau NVV, Hien TT, Lalloo DG, Farrar JJ. Combination antifungal therapy for cryptococcal meningitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Apr 4:368(14):1291-1302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110404. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23550668]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCampitelli M, Zeineddine N, Samaha G, Maslak S. Combination Antifungal Therapy: A Review of Current Data. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2017 Jun:9(6):451-456. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2992w. Epub 2017 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 28496543]

Merry M, Boulware DR. Cryptococcal Meningitis Treatment Strategies Affected by the Explosive Cost of Flucytosine in the United States: A Cost-effectiveness Analysis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016 Jun 15:62(12):1564-8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw151. Epub 2016 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 27009249]

Beardsley J, Wolbers M, Kibengo FM, Ggayi AB, Kamali A, Cuc NT, Binh TQ, Chau NV, Farrar J, Merson L, Phuong L, Thwaites G, Van Kinh N, Thuy PT, Chierakul W, Siriboon S, Thiansukhon E, Onsanit S, Supphamongkholchaikul W, Chan AK, Heyderman R, Mwinjiwa E, van Oosterhout JJ, Imran D, Basri H, Mayxay M, Dance D, Phimmasone P, Rattanavong S, Lalloo DG, Day JN, CryptoDex Investigators. Adjunctive Dexamethasone in HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Feb 11:374(6):542-54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509024. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26863355]

Panackal AA, Wuest SC, Lin YC, Wu T, Zhang N, Kosa P, Komori M, Blake A, Browne SK, Rosen LB, Hagen F, Meis J, Levitz SM, Quezado M, Hammoud D, Bennett JE, Bielekova B, Williamson PR. Paradoxical Immune Responses in Non-HIV Cryptococcal Meningitis. PLoS pathogens. 2015 May:11(5):e1004884. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004884. Epub 2015 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 26020932]

Jitmuang A, Panackal AA, Williamson PR, Bennett JE, Dekker JP, Zelazny AM. Performance of the Cryptococcal Antigen Lateral Flow Assay in Non-HIV-Related Cryptococcosis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2016 Feb:54(2):460-3. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02223-15. Epub 2015 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 26607986]

Vidal JE, Gerhardt J, Peixoto de Miranda EJ, Dauar RF, Oliveira Filho GS, Penalva de Oliveira AC, Boulware DR. Role of quantitative CSF microscopy to predict culture status and outcome in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis in a Brazilian cohort. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2012 May:73(1):68-73. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.01.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22578940]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence