Introduction

Sepsis is a pro- and antiinflammatory response that manifests in the body due to the host-pathogen interaction. Excessive inflammation results in collateral tissue injury, and the antiinflammatory response results in immunosuppression, leading to increased susceptibility to secondary infection. The clinical manifestations of sepsis are highly variable, depending on the initial site of infection, the causative organism, the pattern of acute organ dysfunction, the underlying health status of the patient, and the interval before initiation of treatment.

Severe sepsis occurs as a result of both community-acquired and healthcare-associated infections. While pneumonia continues to be the most common cause of sepsis, both are community-associated. In health care settings, intraabdominal and urinary tract infections are important conduits to the pathological systemic response.[1] Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pneumoniae are the most common gram-positive pathogens, and Escherichia coli, Klebsiella species, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa stand out among the gram-negative microorganisms.[2]

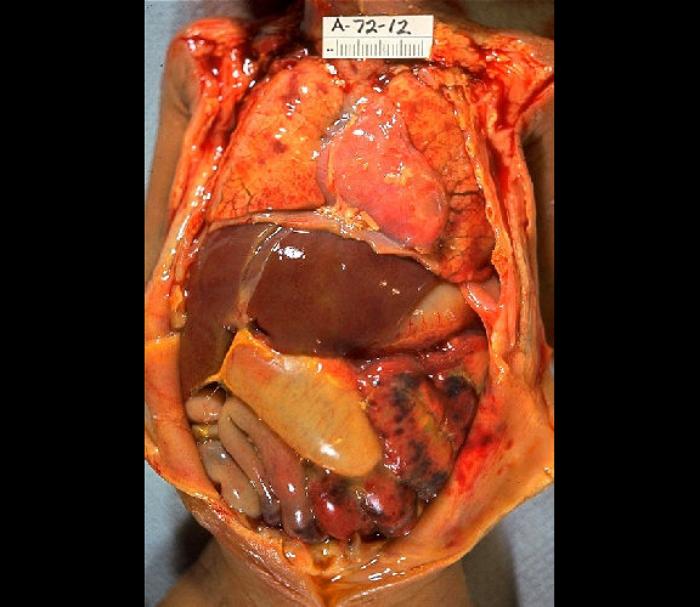

When an infection in the intraabdominal cavity has a primary focus, with identifiable localization, it is called an abscess; when the nidus of the inflammatory response occurs in the serous membrane lining the cavity, it is called peritonitis. Both can lead to a systemic inflammatory/anti-inflammatory response known as peritonitis-induced sepsis. This topic focuses on the fundamental tenets of diagnosing and treating the underlying infection and the complications associated with sepsis (see Image. Severe Septic Peritonitis).

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The clinically significant growth of pathogenic microorganisms into the sterile abdominal cavity is most often accomplished by the violation (most commonly perforation) of the gastrointestinal viscera anywhere along the track, which can be precipitated by a chronic disease process and makes tissue friable and more susceptible to rupture, or an acute onset disease (eg, cholecystitis, pancreatitis). Mechanical violations of the abdominal wall are also responsible for a significant proportion of infections, including but not limited to trauma, surgery, and seeding from dialysis catheters. To a lesser degree, an infection can manifest as a result of hematogenous spread in immunocompromised patients and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in individuals with ascitic fluid collection resultant from cirrhosis, congestive heart failure, and nephrotic disease.

Epidemiology

Several papers analyzing the regional incidence of peritonitis-induced sepsis in a particular population have reported inconclusive data that cannot be extrapolated to generalized observations. However, when dealing specifically with a sub-group of peritonitis, the reported incidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in a patient with ascites is estimated to be between 7% to 30% per year.[3]

Pathophysiology

Gram-negative and/or anaerobic organisms are the usual suspects responsible for infection when perforation is the mechanism of inoculation. The gut flora (E coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae) then release endotoxins responsible for the overreactive inflammatory cascade that causes sepsis. Decreased fibrinolysis mediated through increased plasminogen activator inhibitor activity, increasing fibrin exudates and facilitating large bacterial loads sequestering in the fibrin matrix. The host's logic behind this process is to retard the spread of bacteria beyond the local nidus. Still, this action also creates a physical barrier to advancing host defense mechanisms, thereby, in some cases, prolonging the initial infection and/or abscess formation (see Image. Gross Pathology of Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis).

History and Physical

A good history could give insight into the origins of inoculation; a recent history of abdominal surgery, chronic inflammatory disease, end-stage renal disease, and chronic use of immunosuppressive medication are all important in triggering an appropriate investigation and workup. Concerning signs present in a high percentage of individuals with diagnosed peritonitis include vague constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, abdominal pain, discomfort, diarrhea, and ileus. Approximately 30% of individuals with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are asymptomatic on presentation. During the physical exam, pertinent findings include fever and abdominal tenderness to palpation, which usually is diffuse with wall rigidity in more septic presentations. Conducting a thorough exam is vital, as certain thoracic or pelvic pathologies can mimic peritoneal irritation (empyema causing diaphragmatic irritation and cystitis/pyelonephritis causing peritoneum-adjacent pain).

Evaluation

Patients present with a variable amount of clinical manifestation of the underlying disease process, ranging from insidious mild limited disease to an acute fulminant systemic process. As such, the diagnosis is usually clinical, with some laboratory findings to aid in treatment regimens. The following are pertinent laboratory findings important to mortality and morbidity:

- Leukocytosis in the complete blood count, evidence of renal and/or hepatic dysfunction (by comprehensive metabolic panel and urinalysis, denoting possible multiple organ dysfunction or pre-existing comorbidities)

- Positive blood cultures and

- Peritoneal fluid analysis

Fluid analysis is important for the diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, with the most sensitive indicator being a neutrophil count greater than 250 cells/microliter. The fluid should also be analyzed for glucose, protein, lactate dehydrogenase, cell count, Gram stain, and aerobic and anaerobic cultures. The SAAG (serum-ascites albumin gradient) is used to determine the composition of the ascitic fluid (transudative vs exudative), with the differential diagnosis depending on the gradient; a gradient greater than 1.1 g/dL is indicative of a transudative fluid-related to increased hydrostatic pressures, such as portal-hypertension and/or thrombosis, congestive heart failure, and Budd–Chiari syndrome to name a few. A low SAAG (less than 1.1 g/dL) indicates fluid associated with increased portal pressures, eg, infections (tuberculosis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), neoplasms, nephrotic disease, and other inflammatory processes such as pancreatitis and serositis.[4] The severity of the illness is managed with careful consideration of sepsis protocols, including monitoring parameters reflective of end-organ tissue perfusion mean arterial pressure, lactate level, evidence of end-organ damage such as encephalopathy, renal dysfunction, and evaluation for the necessity of supportive care measures like ventilatory or pressor support.

Treatment / Management

The primary focus of management is identifying and treating the offending agent(s) via antibiotics and/or surgical intervention. The non-operative measure includes broad-spectrum antibiotic administration with appropriate stewardship, tailoring the regimen to increase efficacy by targeting the identified microorganisms. Ultrasound or computed tomography-guided abscess drainage, percutaneous/endoscopic stent placement, and important non-surgical interventions are also included.[5] Supplemental therapies are focused on diminishing the effects of toxin release, end-organ damage, and host-mediated inflammatory response pathognomonic for sepsis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential for the observed symptomatology can be wide because of the broad range of sometimes vague constitutional symptoms. Anatomical location is important in considering the other possible disease processes that must be ruled out. Pathology in all 4 surrounding surfaces has to be considered, including:

- Diaphragmatic irritation (elicited by thoracic conditions, eg, empyema, inferiorly located pleural disease)

- Pelvic pathology (eg, cystitis, urinary obstruction)

- Retroperitoneal diseases (eg, pyelonephritis, hematoma)

- Abdominal wall issues (eg, rectus infection/hematoma)

Also, the following can be causes of inflammation outside of the abdominal cavity:

- Chemical irritants (eg, bile, gastric juices, blood)

- Systemic inflammatory disease with intra-abdominal manifestations (eg, Crohn disease, allergic vasculitis)

In addition, some vascular abnormalities can cause widespread inflammatory responses, including mesenteric ischemia/thrombosis and ischemic colitis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A well-functioning, efficient interprofessional team is necessary to execute the appropriate clinical measures to treat patients with sepsis as time management is critical in predicting the overall outcomes. A well-established consensus committee of 55 experts representing 25 international organizations formulated the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, with the most recent iteration developed in 2016. In the guidelines, recommendations are made concerning the hospital-derived analytical processes that should be implemented to assess the effectiveness of each institution's sepsis protocol. The proposals include target metrics to monitor goal attainment, data collection, and ongoing feedback criticizing the program's effectiveness. These recommendations are made based on the meta-analysis of 50 observational studies, illustrating that performance improvement programs had a direct correlation with a significant increase in compliance with the study's guidelines, thus reducing mortality. Mandating compliance with an established sepsis protocol is not enough; there must be a recognized method by which adherence, efficiency of execution, and overall outcomes can be analyzed.[6]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Gross Pathology of Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Autopsy of an infant with abdominal distention, necrosis, hemorrhage, and peritonitis due to perforation.

Edwin P Ewing Jr, MD/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Critical care medicine. 2001 Jul:29(7):1303-10 [PubMed PMID: 11445675]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOpal SM, Garber GE, LaRosa SP, Maki DG, Freebairn RC, Kinasewitz GT, Dhainaut JF, Yan SB, Williams MD, Graham DE, Nelson DR, Levy H, Bernard GR. Systemic host responses in severe sepsis analyzed by causative microorganism and treatment effects of drotrecogin alfa (activated). Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2003 Jul 1:37(1):50-8 [PubMed PMID: 12830408]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLinde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC. Severe sepsis epidemiology: sampling, selection, and society. Critical care (London, England). 2004 Aug:8(4):222-6 [PubMed PMID: 15312201]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRiggio O,Angeloni S, Ascitic fluid analysis for diagnosis and monitoring of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2009 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 19701963]

Marshall JC. Intra-abdominal infections. Microbes and infection. 2004 Sep:6(11):1015-25 [PubMed PMID: 15345234]

Barrier KM. Summary of the 2016 International Surviving Sepsis Campaign: A Clinician's Guide. Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 2018 Sep:30(3):311-321. doi: 10.1016/j.cnc.2018.04.001. Epub 2018 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 30098735]