Introduction

Heme is a porphyrin ring complexed with ferrous iron and protoporphyrin IX. Heme is an essential prosthetic group in proteins that is necessary as a subcellular compartment to perform diverse biological functions like hemoglobin and myoglobin.[1] Other enzymes which use heme as a prosthetic group includes cytochromes of the electron transport chain, catalase, and nitric oxide synthase. The major tissues for heme synthesis are bone marrow by erythrocytes and the liver by hepatocytes.

Fundamentals

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Fundamentals

Heme synthesis occurs in the cytosol and mitochondria; heme acquisition also occurs through intestinal absorption and intercellular transport.[2] Heme is a component of different biological structures mainly, hemoglobin, others include myoglobin, cytochromes, catalases, heme peroxidase, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. There are different forms of biological heme. The most common type is heme b, found in hemoglobin leads to a derivative of other heme groups. Heme a exists in cytochrome a and heme c in cytochrome c; they are both involved in the process of oxidative phosphorylation.

5'-Aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALA-S) is the regulated enzyme for heme synthesis in the liver and erythroid cells. There are two forms of ALA Synthase, ALAS1, and ALAS2. All cells express ALAS1 while only the liver and bone marrow expresses ALAS2. The gene for ALAS2 is on the X-chromosome.

Cellular Level

Porphyrin synthesis is the process that produces heme. Heme synthesis occurs partly in the mitochondria and partly in the cytosol. The biosynthesis involves an eight-step enzymatic pathway. Heme biosynthesis starts in mitochondria with the condensation of succinyl Co-A from the citric acid cycle and an amino acid glycine. They combine to produce a key heme intermediate, 5'-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) in mitochondria catalyzed by the pyridoxal phosphate-requiring (vitamin B6) enzyme, aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS).[3] This reaction is the rate-limiting step in the pathway.[4]

The ALA molecule formed exit the mitochondria into the cytosol where two molecules of ALA condense to produce the pyrrole ring compound porphobilinogen (PBG) catalyzed by a zinc-requiring enzyme, ALA dehydratase enzyme (also called porphobilinogen synthase). The next step of the pathway involves condensation of four molecules of porphobilinogen, aligned to form the linear hydroxymethylbilane (HMB), catalyzed by porphobilinogen deaminase (PBG deaminase) also known as hydroxymethylbilane synthase.

Closure of the linear HMB forms an asymmetric pyrrole ring D called uroporphyrinogen III, catalyzed by uroporphyrinogen-III synthase. This step is vital as an incorrect porphyrin ring formation leads to protoporphyria. The correct porphyrin ring III forms, and then the side chains of uroporphyrinogen III are modified, catalyzed by uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase to produce coproporphyrinogen III.

Following its synthesis, coproporphyrinogen III gets transported into mitochondria. The coproporphyrinogen III then gets decarboxylated by coproporphyrinogen oxidase enzyme to form the colorless product protoporphyrinogen IX.

Finally, protoporphyrinogen IX is converted to protoporphyrin IX using protoporphyrinogen oxidase. The final reaction involves the insertion of ferrous iron into protoporphyrin IX catalyzed by the enzyme ferrochelatase leading to the formation of heme.[5]

Molecular Level

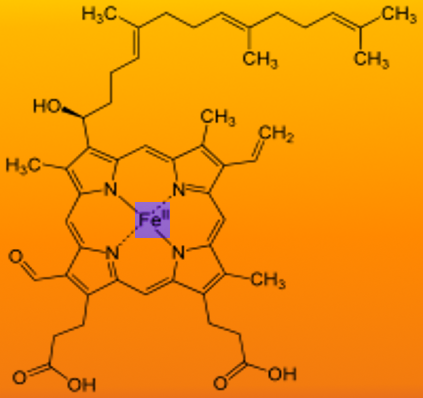

Heme is ferrous protoporphyrin IX- four pyrrole rings linked via methenyl bridges. The side chains of heme b are methyl, vinyl, methyl, propionyl, and asymmetric ring D: propionyl, methyl.

Function

Heme has a variety of functions. As a cofactor, it allows for the following[1]:

- Oxygen transport in hemoglobin

- Storage in myoglobin

- A prosthetic group for cytochrome p450 enzymes

- A reservoir of iron

- Electron shuttle of enzymes in the electron transport chain

- Cellular respiration

- Signal transduction-heme regulates the antioxidant response to circadian rhythms, microRNA processing

- Cellular differentiation and proliferation

Mechanism

Heme synthesis in erythroid cells: heme is synthesized for incorporation into hemoglobin. In immature erythrocytes (reticulocytes), heme stimulates protein synthesis of the globin chains and erythropoietin stimulates heme. The kidney releases erythropoietin hormone at low oxygen levels in tissues and stimulates RBC and hemoglobin synthesis. Accumulation of heme in erythroid cells is desired as it leads to more globin chain synthesis and required in erythroblast maturation. When red cells mature both heme and hemoglobin synthesis ceases. Additionally, control of heme biosynthesis in erythrocytes is controlled by the availability of intracellular iron.

Heme synthesis in the liver is highly variable and tightly regulated as heme outside proteins causes damage to hepatocytes at high concentration. In the liver, cytochrome P450 (CYP 450) requires heme. Liver contains the isoform ALAS1 which is expressed in most cells. Drugs increase ALAS1 activity as they lead to CYP 450 synthesis which needs heme. Low intracellular heme concentration stimulates synthesis of ALAS1. Heme synthesis stops when heme is not incorporated into proteins and when heme and hemin accumulate.

Hemin decreases the synthesis of ALA synthase 1 in three ways: Hemin reduces the synthesis of ALAS1 mRNA, destabilizes ALAS1 mRNA, and inhibits import of the enzyme ALAS1 from the cytosol into mitochondria.

Pathophysiology

A defect or mutation in 5’- aminolevulinic acid synthase 2 (ALAS2) leads to a disorder called X-linked sideroblastic anemia. It reduces protoporphyrin production and decreases heme. However, Iron continues to enter the erythroblast leading to an accumulation in the mitochondria and therefore a manifestation of the disease.

During the biosynthetic pathway, the linear hydroxymethylbilane can spontaneously form a “faulty” porphyrin ring when not immediately used as a substrate for uroporphyrinogen synthesis. If uroporphyrinogen III synthase is deficient, then hydroxymethylbilane spontaneously closes and forms a different molecule called uroporphyrinogen I. Uroporphyrinogen leads to the formation of coproporphyrinogen I. This molecule does not result in the formation of heme.

Clinical Significance

Heme synthesis is a biochemical pathway which requires a number of steps, substrates, and enzymes. A deficiency in an enzyme or substrate leads to accumulation of intermediates of heme synthesis in blood, tissues, and urine leading to a clinically significant outcome of a group of disorders called porphyrias. Porphyrias are hepatic or erythropoietic. They can be acute or chronic, lead to neurologic dysfunction, mental disturbance or photosensitivity. Defects of heme synthesis after formation of hydroxymethylbilane leads to photosensitivity of patients. Other symptoms include a change in urine color, abdominal pain, abdominal colic, highly agitated state, tachycardia, respiratory problems, nausea, confusion, weakness of lower extremities.

Porphyrias are acute intermittent, congenital erythropoietic porphyria, porphyria cutanea tarda, hereditary coproporphyria.

Acute intermittent porphyria: This occurs due to a mutation in hydroxymethylbilane synthase, which leads to an accumulation of ALA and porphobilinogen. It does not affect erythroblasts. The disease presents as severe abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation, abdominal distention, and behavioral changes (irritability, insomnia, emotional lability),[6] hypertension and tachycardia. Lab results show elevated urinary porphobilinogen and the urine darkens on exposure to air and sunlight. Patients presenting with acute intermittent porphyria are not photosensitive.

Porphyria cutanea tarda: This variant is the most common type of porphyria. It is due to a deficiency or decreased activity in uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD). It can be acquired or hereditary (autosomal dominant). Uroporphyrin accumulates in the urine. Symptoms include photosensitivity leading to blisters developing in sun-exposed areas and hyperpigmentation, and hepatic injury. Treatment includes avoidance of sunlight, hydroxychloroquine, and phlebotomy.

Erythropoietic porphyria: This occurs due to a deficiency in ferrochelatase, the enzyme responsible for the final formation of heme in the biosynthesis pathway by combining protoporphyrin IX and ferrous iron. Deficiency leads to an accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in erythrocytes. Symptoms include painful photosensitivity- swelling burning and itching in sun-exposed areas; sometimes hepatic dysfunction.

Lead Poisoning: Lead interacts with zinc cofactors for ALA dehydratase and ferrochelatase leading to inhibition of these two enzymes in the biochemical biosynthetic pathway of heme. This inhibition leads to mostly ALA and some protoporphyrin IX accumulating in urine. Symptoms include abdominal pain, vomiting, fatigue irritability and developmental disability in children.

Media

References

Yuan X, Rietzschel N, Kwon H, Walter Nuno AB, Hanna DA, Phillips JD, Raven EL, Reddi AR, Hamza I. Regulation of intracellular heme trafficking revealed by subcellular reporters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016 Aug 30:113(35):E5144-52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609865113. Epub 2016 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 27528661]

Chung J, Chen C, Paw BH. Heme metabolism and erythropoiesis. Current opinion in hematology. 2012 May:19(3):156-62. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328351c48b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22406824]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFujiwara T, Harigae H. Biology of Heme in Mammalian Erythroid Cells and Related Disorders. BioMed research international. 2015:2015():278536. doi: 10.1155/2015/278536. Epub 2015 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 26557657]

Zhang T, Bu P, Zeng J, Vancura A. Increased heme synthesis in yeast induces a metabolic switch from fermentation to respiration even under conditions of glucose repression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2017 Oct 13:292(41):16942-16954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.790923. Epub 2017 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 28830930]

Kim HJ, Khalimonchuk O, Smith PM, Winge DR. Structure, function, and assembly of heme centers in mitochondrial respiratory complexes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012 Sep:1823(9):1604-16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.008. Epub 2012 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 22554985]

Balwani M, Singh P, Seth A, Debnath EM, Naik H, Doheny D, Chen B, Yasuda M, Desnick RJ. Acute Intermittent Porphyria in children: A case report and review of the literature. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2016 Dec:119(4):295-299. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.10.005. Epub 2016 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 27769855]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence